New Orleans Massacre of 1866

| New Orleans massacre of 1866 | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Reconstruction era | |

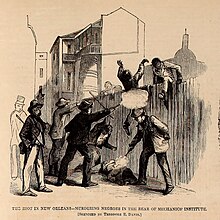

"Murdering Negroes in the rear of the Mechanics' Institute" – Sketched by Theodore R. Davis (Harper's Weekly, August 25, 1866) | |

| Location | New Orleans, Louisiana |

| Date | July 30, 1866 |

| Target | Anti-racist marchers |

Attack type | Mass murder |

| Deaths | 34–200 African Americans killed and 4 whites killed[1][2] |

| Injured | 150 |

| Perpetrators | Ex-Confederates, white supremacists, and members of the New Orleans Police Force[3] |

The New Orleans massacre of 1866 occurred on July 30, when a peaceful demonstration of mostly Black Freedmen was set upon by a mob of white rioters, many of whom had been soldiers of the recently defeated Confederate States of America, leading to a full-scale massacre.[4] The violence erupted outside the Mechanics Institute, site of a reconvened Louisiana Constitutional Convention.[5] According to the official report, a total of 38 were killed and 146 wounded, of whom 34 dead and 119 wounded were Black Freedmen. Unofficial estimates were higher.[6] Gilles Vandal estimated 40 to 50 Black Americans were killed and more than 150 Black Americans wounded.[7] Others have claimed nearly 200 were killed.[2] In addition, three white convention attendees were killed, as was one white protester.[8]

During much of the American Civil War, New Orleans had been occupied and under martial law imposed by the Union. On May 12, 1866, Mayor John T. Monroe, a Democrat who had ardently supported the Confederacy, was reinstated as acting mayor, the position he held before the war. Judge R. K. Howell was elected as chairman of the convention, with the goal of increasing participation by voters likely to vote for removal of the Black Codes.[9]

The massacre expressed conflicts deeply rooted in the social structure of Louisiana. The New Orleans massacre was a continuation of a longer shooting war over slavery (beginning with Bleeding Kansas in 1859), of which the 1861–1865 hostilities were merely the largest part.[10] More than half of the whites were Confederate veterans and nearly half of the Black Americans were veterans of the Union army. The national reaction of outrage at the earlier Memphis riots of 1866 and the New Orleans Massacre helped the Radical Republicans win a majority in both houses of Congress in the 1866 midterm elections. The riots catalyzed support for the Fourteenth Amendment, extending suffrage and full citizenship to freedmen, and the Reconstruction Act, to establish military districts for the national government to oversee areas of the South and work to change their social arrangements.

Tension builds

The State Constitutional Convention of 1864 authorized greater civil freedoms to Blacks within Louisiana yet provided no voting rights for any people of color. Free people of color, who were mixed-race, had been an important part of New Orleans for more than a century and were established as a separate class in the colonial period, before United States annexation of the territory in 1803. Many were educated and owned property and were seeking the vote. In addition, Republicans had the goals of extending the suffrage to freedmen and eliminating the Black Codes passed by the legislature. They reconvened the convention and succeeded in incorporating these goals.[11]

White Democrats by and large considered the reconvened convention illegal, as they said that the voters, then limited to whites only, had accepted the constitution. White supremacy was a plank of their 1865 state party platform: "Resolved, that we hold this to be a Government of White People, made and to be perpetuated for the exclusive political benefit of the White Race, and in accordance with the constant adjudication of the United States Supreme Court, that the people of African descent cannot be considered as citizens of the United States, and that there can in no event nor under any circumstances be any equality between the white and other Races."[6] They opposed the goals articulated by Rufus King Cutler: "We have thirty to thirty-five thousand negro and colored voters in Louisiana, and about twenty-eight to thirty-thousand white voters. We could have all the negro men and the colored men to vote with the Union men, and that, with the disenfranchisement of the leading rebels, would give the ascendancy to the unionists, and I think they could sustain themselves...with sufficient military force to enforce these provisions, we could establish a government that would be substantial and we could sustain it after its establishment."[12]

In addition, they argued legal technicalities: the elected chairman Howell had left the original convention before its conclusion and was, therefore, not considered a member, the constitution was accepted by the people, and the radicals, only 25 of whom were present at the convention of 1864, did not make up a majority of the original convention.

On July 27, Black supporters of the convention, including approximately 200 war veterans, met at the steps of the Mechanics Institute. They were stirred by speeches of abolitionist activists, most notably Anthony Paul Dostie and former Governor of Louisiana Michael Hahn. The men proposed a parade to the Mechanics Institute on the day of the convention to show their support.

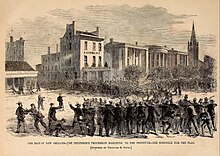

Massacre

The convention met at noon on July 30, but a lack of a quorum caused postponement to 1:30.[13] When the convention members left the building, they were met by the black marchers with their marching band. On the corner of Common and Dryades streets, across from the Mechanics Institute, a group of armed whites awaited the black marchers.[14] This group was composed largely of Democrats who opposed abolition; most were ex-Confederates who wanted to disrupt the convention and the threat to white supremacy the increasing political and economic power of blacks in the state represented.

It is not known which group fired first, but within minutes, there was a battle in the streets. The black marchers were unprepared and many were unarmed; they rapidly dispersed, with many seeking refuge within the Mechanics Institute. The white mob brutally attacked blacks on the street and some entered the building:

The whites stomped, kicked, and clubbed the black marchers mercilessly. Policemen smashed the institute’s windows and fired into it indiscriminately until the floor grew slick with blood. They emptied their revolvers on the convention delegates, who desperately sought to escape. Some leaped from windows and were shot dead when they landed. Those lying wounded on the ground were stabbed repeatedly, their skulls bashed in with brickbats. The sadism was so wanton that men who kneeled and prayed for mercy were killed instantly, while dead bodies were stabbed and mutilated.

— Ron Chernow, "Grant" (2017)[15]

Federal troops responded to suppress the riot and jailed many of the white insurgents. The governor declared the city under martial law until August 3.

Nearly 200 people were killed, almost all African Americans.[2] Notable among the dead were Victor Lacroix, John Henderson Jr.[16] (son of John Henderson, a US Senator from Mississippi), Dr. A. P. Dostie,[17] and Rev. Mr. Jotham Horton.[18]

Reaction

The national reaction to the New Orleans riot, coupled with the earlier Memphis riots of 1866, was one of heightened concern about the current Reconstruction strategy and desire for a change of leadership. In the 1866 midterm elections, the Republican Party increased their majority further, ultimately gaining 77% of the seats in Congress. This enabled them to overturn any veto by Democratic President Andrew Johnson, who was opposed to granting equal rights to freedmen. In both houses of Congress, the faction known as the "Radical Republicans" prevailed and imposed much harsher terms of Reconstruction on the states of the former Confederacy.[19]

On March 2, 1867, the First Reconstruction Act was passed – over President Johnson's veto[20] – to provide for more federal control in the South. Military districts were created to govern the region until violence could be suppressed and a more democratic political system established. Ex-Confederate soldiers and leaders, most of whom were white supporters of the Democratic Party, were temporarily disenfranchised, and the right of suffrage was to be enforced for free people of color. Under the act, Louisiana was assigned to the Fifth Military District, commanded by Philip Sheridan. On assuming command of the district, the general had announced his intention to avoid the wholesale removal of civil officials unless the authorities failed "to carry out the provisions of the law or impeded reorganization". However, he soon decided that a number of officials had to go. Displeased with the civil authorities' handling of the New Orleans riot the previous summer and their failure to bring the perpetrators to justice, Sheridan dismissed Mayor Monroe, State Attorney General Herron, and Judge Edmund Abell from office and replaced them with Republicans whom he believed would faithfully execute their duties. He also removed an aide to the New Orleans police chief for intimidating black voters and annulled a law designed to prevent former federal soldiers from serving on the New Orleans police force, stipulating that in the future one-half of the policemen be Union Army veterans.[21]

The editorial department of Harper's Weekly held that President Johnson tacitly approved the massacre by signaling that he would not use federal power to interfere in ex-Confederate paramilitary action:[22]

The President knew, as every body else knew, the inflamed condition of the city of New Orleans. He had read, as we had all read, the fiery speeches of both parties. He knew, unless he had chosen willfully to ignore, the smothered hatred of the late rebels toward the Union men of every color. He may have considered the "Conservatives" wise, humane, and peaceful. He may have thought the Radicals wild and foolish. He knew that the Mayor was a bitter rebel, whom he had pardoned into office. He knew that the courts had denounced the Convention, and he was expressly informed that they meant to indict the members. He could not affect ignorance of the imminent danger of rioting and bloodshed. Still, if, as he constantly asserts, Louisiana is rightfully in the same relation to the Union that New York is, he had no authority to say a word or to do an act in that State except "on application of the Legislature, or of the Executive when the Legislature can not be convened." Why did he presume, then, to judge of the authority of the Convention? What has the President of the United States to do with the manner in which delegates to a State Convention are selected? If his own assertion be correct as to the present relation of Louisiana to the Union, the President convicts himself of the most extraordinary and passionate act of executive usurpation and federal centralization recorded in our history. ¶ If, however, he had any right whatever to intervene in the absence of a demand from the Legislature or the Governor, it was derived from the fact that Louisiana is held by the military power of the United States, in which case her present relation to the Union is not what the President declares it to be, and he has ample and absolute power to do in that State whatever is necessary to keep the peace. And he knew, as he knew his own existence, that a simple word to the military commander to preserve the peace at all hazards would prevent disorder and save lives. He did not speak that word. Assuming to plant himself upon the Constitution, which by his very act he violated, he telegraphed to the Attorney-General of the State. He threw his whole weight upon the side of those from whom he knew in the nature of things the disorder would proceed, and from whom it did proceed. He knew the city was tinder, and he threw in a spark. Every negro hater and every disloyal ruffian knew from the President's dispatch that the right of the citizens to assemble and declare their views would not be protected. The Mayor's proclamation was a covert but distinct invitation to riot. He announced to a city seething with passionate hatred of the Convention, that it would "receive no countenance from the President." It was simply saying, "The Convention is at your mercy." ¶ And the mob so understood it. A procession of negroes carrying a United States flag was attacked. It defended itself; and the work which one word from the President would have stopped, and which he had the full authority to speak if he could speak at all, went on to its awful result. The rebel flag was again unfurled. The men who had bravely resisted it for four years were murdered under its encouragement, and while they were still lying warm in their blood the President telegraphed that they were "an unlawful assembly," and that "usurpation will not be tolerated" – words which he had no shadow of authority to utter except by the same right which empowered him to save all those lives; a right which he declined to exercise.

Benjamin Butler, an early advocate for the prospect of impeaching President Andrew Johnson, as early as October 1866 proposed alleged complicity in the massacre as one of several grounds for impeaching Johnson.[23] After his election to the United States House of Representatives in the November 1866 House elections, Congressman-elect Butler continued to assert that, among several grounds for impeaching Johnson, was that Johnson allegedly, "unlawfully, corruptly, and wickedly confederating and conspiring with one John T. Monroe...and other evil disposed persons, traitors, and rebels," in relation to the massacre.[24] Incidentally, in November 1867, when Thomas Williams authored the majority report of House Committee on the Judiciary at the conclusion of first impeachment inquiry against Andrew Johnson, the report recommending the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson outlined seventeen specific acts of alleged malfeasance by Johnson, the sixteenth of which alleged that Johnson had encouraged the massacre (which the report characterized as, "the murder of loyal citizens in New Orleans by a Confederate mob pretending to act as a police").[25] However, the United States House of Representatives voted 57–108 against impeaching Johnson on December 7, 1867.[26] When Johnson was impeached months later, none of the articles of impeachment related to the New Orleans massacre.[27]

Gallery

- "Timely warning to Union men – The New Orleans Convention or Massacre - Which is more illegal?" (Harper's Weekly, September 8, 1866)

- Detail of Andy's Trip, depicting the massacre and verbal exchanges between the president and the crowds during Johnson's Swing Around the Circle tour (Harper's Weekly, October 22 1866)

- Amphitheatrum Johnsonianum – Massacre of the Innocents at New Orleans – July 30, 1866 (Harper's Weekly, September 8, 1866) has been called "one of the most important cartoons that Thomas Nast ever drew."[28]

- This 1867 image of Andy Johnson (in a privy) at the New Orleans massacre was part of Nast's 1867 Grand Caricaturama cycle of 33 historical paintings[29]

See also

- Freedmen massacres

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- Fifth Military District

- 2022 Buffalo shooting

References

- Notes

- ^ "Reconstruction in America Racial Violence after the Civil War, 1865–1876". Equal Justice Initiative. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c Ball (2020), p. 211.

- ^ Stolp-Smith, Michael (April 7, 2011). "New Orleans Massacre (1866) •".

- ^ Scott, Mike (30 June 2020). "1866 New Orleans massacre remembered as a city-led racial attack a year after the Civil War ended". NOLA.com.

- ^ Vandal (1984), p. 137.

- ^ a b Reynolds, Donald E. (Winter 1964). "The New Orleans Riot of 1866, Reconsidered". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 5 (1): 5–27.

- ^ Vandal (1978), p. 225.

- ^ Bell, Caryn Cossé (1997). Revolution, Romanticism, and the Afro-Creole Protest Culture in Louisiana 1718–1868. Baton Rouge, La.: LSU Press. p. 262.

- ^ Kendall (1992), p. 305.

- ^ "300 unique New Orleans moments: Mechanics Institute the center of 1866 riot | 300 for 300 | nola.com". www.nola.com. 17 October 2017. Retrieved 2023-07-21.

- ^ Kendall (1992), p. 308.

- ^ "Report of the Select committee on the New Orleans Riots". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. p. 45. Retrieved 2023-07-21.

- ^ Bell (1997), p. 261.

- ^ Kendall (1992), p. 312.

- ^ Chernow (2017), pp. 574–575.

- ^ "N.O. Picayune". The Weekly Intelligencer. 1866-08-17. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ Times, Special Dispatches to the New-York (1866-07-31). "GREAT RIOT; Anarchy and Bloodshed in New-Orleans". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ McEvoy, Bill (2023-05-24). "Civil War Clergy at Mount Auburn Cemetery: Jotham Horton". Watertown News. Watertown, Mass. Retrieved 2023-07-21.

- ^ Radcliff (2009), pp. 12–16.

- ^ Johnson, Andrew. "Veto for the first Reconstruction Act March 2, 1867 To the house of Representatives". American History: From Revolution to Reconstruction and beyond... University of Groningen. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ^ Bradley, Mark. "The Army and Reconstruction, 1865–1877" (PDF). U.S. Army Center of Military History. United States Army. Retrieved 14 October 2023.

- ^ "Item 003".

- ^ "Impeachment". Newspapers.com. Perrysburg Journal. October 26, 1866. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ "The Proposed Impeachment". Newspapers.com. The Evening Telegraph (Philadelphia). 1 Dec 1866. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ Hinds, Asher C. (4 March 1907). "HINDS' PRECEDENTS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF THE UNITED STATES INCLUDING REFERENCES TO PROVISIONS OF THE CONSTITUTION, THE LAWS, AND DECISIONS OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE" (PDF). United States Congress. p. 830. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ "The Case for Impeachment, December 1867 | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Stephen W. Stathis and David C. Huckabee. "Congressional Resolutions on Presidential Impeachment: A Historical Overview" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved December 31, 2019 – via University of North Texas Libraries, Digital Library, UNT Libraries Government Documents Department.

- ^ HarpWeek. "Amphitheatrum Johnsonianum". www.impeach-andrewjohnson.com. Retrieved 2023-07-20.

- ^ "The Massacre at New Orleans". Library of Congress. 1867.

- Bibliography

- Ball, Edward (2020). Life of a Klansman: A Family History in White Supremacy. Baton-Rouge: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Bell, Caryn Cossé (1997). Revolution, Romanticism, and the Afro-Creole Protest Tradition in Louisiana 1718–1868. Baton-Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- Chernow, Ron (2017). Grant. Penguin.

- Du Bois, W.E.B. (1935). "XI. The Black Proletariat in Mississippi and Louisiana". Black Reconstruction. New York: Russell and Russell.

- Fortier, Alcée (1904). A History of Louisiana, Volume 4, Part 2. Paris: Goupil and Company. p. 58.

new orleans riot.

- Foster, J. Ellen (1892). Jotham Warren Horton. B.S. Adams.

- Hollandsworth, James G. (2004). An Absolute Massacre: The New Orleans Race Riot of July 30, 1866. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0807130292.

- Kendall, John (1922). "The Riot of 1866". History of New Orleans. Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Company.

- McPherson, Edward (1875). The Political History of the United States of America During the Period of Reconstruction. Washington, D.C.: Solomans and Chapman.

- Radcliff, Michael A. (2009). The Custom House Conspiracy. New Orleans: Crescent City Literary Classics.

- Reed, Emily Hazen (1868). Life of A. P. Dostie, Or, The Conflict in New Orleans. New York: W.P. Tomlinson. p. 362.

new orleans riot.

- Riddleberger, Patrick W. (1979). 1866, The Critical Year Revisited. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Trefousse, Hans L. (1999). "Andrew Johnson". American National Biography. Vol. 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Vandal, Gilles (1984). The New Orleans Riot of 1866: Anatomy of a Tragedy. Center for Louisiana Studies.

- Wainwright, Irene. Administrations of the Mayor's of New Orleans: Monroe. Louisiana Division New Orleans Public Library. Retrieved February 4, 2007.

- Warmoth, Henry Clay (1930). War, Politics and Reconstruction. New York: Macmillan. p. 49.

External links

- "New Orleans Race Riot". Center for History and New Media, George Mason University. 2002.

- "The New Orleans Massacre". Harper's Weekly. March 30, 1867. p. 202.

![Amphitheatrum Johnsonianum – Massacre of the Innocents at New Orleans – July 30, 1866 (Harper's Weekly, September 8, 1866) has been called "one of the most important cartoons that Thomas Nast ever drew."[28]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c8/Amphitheatrum_Johnsonian_%E2%80%93_Massacre_of_the_Innocents_at_New_Orleans_%E2%80%93_July_30%2C_1866.jpg/381px-Amphitheatrum_Johnsonian_%E2%80%93_Massacre_of_the_Innocents_at_New_Orleans_%E2%80%93_July_30%2C_1866.jpg)

![This 1867 image of Andy Johnson (in a privy) at the New Orleans massacre was part of Nast's 1867 Grand Caricaturama cycle of 33 historical paintings[29]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9f/Cartoonist_Thomas_Nast_drew_this_political_cartoon_The_Massacre_at_New_Orleans_-_cropped.jpg/450px-Cartoonist_Thomas_Nast_drew_this_political_cartoon_The_Massacre_at_New_Orleans_-_cropped.jpg)