Treaty of Nanking

| Treaty of Peace, Friendship, and Commerce Between Her Majesty the Queen of Great Britain and Ireland and the Emperor of China[1] | |

|---|---|

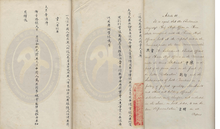

Signing of the treaty on board HMS Cornwallis | |

| Signed | 29 August 1842 |

| Location | Nanjing, Qing Empire |

| Effective | 26 June 1843 |

| Condition | Exchange of ratifications |

| Signatories | |

| Parties | |

| Depositary | National Palace Museum, Taiwan The National Archives, United Kingdom |

| Languages | English and Chinese |

| Full text | |

| Treaty of Nanking | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 南京條約 | ||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 南京条约 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Hong Kong |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

| By topic |

The Treaty of Nanking was the peace treaty which ended the First Opium War (1839–1842) between Great Britain and the Qing dynasty of China on 29 August 1842. It was the first of what the Chinese later termed the "unequal treaties".

In the wake of China's military defeat, with British warships poised to attack Nanjing (then romanized as Nanking), British and Chinese officials negotiated on board HMS Cornwallis anchored in the Yangtze at the city. On 29 August, British representative Sir Henry Pottinger and Qing representatives Keying, Yilibu, and Niu Jian signed the treaty, which consisted of thirteen articles.

The treaty was ratified by the Daoguang Emperor on 27 October and Queen Victoria on 28 December. The exchange of ratification took place in Hong Kong on 26 June 1843. The treaty required the Chinese to pay an indemnity, to cede the Island of Hong Kong to the British as a colony, to essentially end the Canton system that had limited trade to that port and allow trade at Five Treaty Ports. It was followed in 1843 by the Treaty of the Bogue, which granted extraterritoriality and most favoured nation status.

Background

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Britain faced a growing trade deficit with China. Britain could offer nothing to China to match the growing importation of Chinese goods to Britain, such as tea and porcelain. In British India, opium was grown on plantations and auctioned to merchants, who then sold it to Chinese who smuggled it into China (Chinese law forbade the importation and sale of opium).[2] When Lin Zexu seized this privately owned opium and ordered the destruction of opium at Humen, Britain first demanded reparations, then declared what became known as the First Opium War. Britain's use of recently invented military technology produced a crushing victory and allowed it to impose a one-sided treaty. [3][better source needed]

The first working draft for articles of a treaty was prepared at the Foreign Office in London in February 1840. The Foreign Office was aware that preparing a treaty containing Chinese and English characters would need special consideration. Given the distance separating the countries, the parties realised that some flexibility and a departure from established procedure in preparing treaties might be required.[4][full citation needed]

Terms

Foreign trade

The fundamental purpose of the treaty was to change the framework of foreign trade imposed by the Canton System, which had been in force since 1760. Under Article V, the treaty abolished the former monopoly of the Cohong and their Thirteen Factories in Canton. Four additional "treaty ports" opened for foreign trade alongside Canton (Shameen Island from 1859 until 1943): Xiamen (or Amoy; until 1930), Fuzhou, Ningbo and Shanghai (until 1943),[5][6] where foreign merchants were to be allowed to trade with anyone they wished. Britain also gained the right to send consuls to the treaty ports, which were given the right to communicate directly with local Chinese officials (Article II). The treaty stipulated that trade in the treaty ports should be subject to fixed tariffs, which were to be agreed upon between the British and the Qing governments (Article X).[7]

Reparations and demobilisation

The Qing government was obliged to pay the British government 6 million silver dollars for the opium that had been confiscated by Lin Zexu in 1839 (Article IV), 3 million dollars in compensation for debts that the merchants in Canton owed British merchants (Article V), and a further 12 million dollars in war reparations for the cost of the war (Article VI). The total sum of 21 million dollars was to be paid in instalments over three years and the Qing government would be charged an annual interest rate of 5 percent for the money that was not paid in a timely manner (Article VII).[7]

The Qing government undertook to release all British prisoners of war (Article VIII), and to give a general amnesty to all Chinese subjects who had cooperated with the British during the war (Article IX).[7]

The British on their part, undertook to withdraw all of their troops from Nanjing, the Grand Canal and the military post at Zhenhai, as well as not to interfere with China trade generally, after the emperor had given his assent to the treaty and the first instalment of money had been received (Article XII). British troops would remain in Gulangyu and Zhaobaoshan until the Qing government had paid reparations in full (Article XII).[7]

Cession of Hong Kong

In 1841, a rough outline for a treaty was sent for the guidance of Plenipotentiary Charles Elliot. It had a blank after the words "the cession of the islands of". Pottinger sent this old draft treaty on shore, with the letter s struck out of islands and the words Hong Kong placed after it.[8] Robert Montgomery Martin, treasurer of Hong Kong, wrote in an official report:

The terms of peace having been read, Elepoo the senior commissioner paused, expecting something more, and at length said "is that all?" Mr. Morrison enquired of Lieutenant-colonel Malcolm [Pottinger's secretary] if there was anything else, and being answered in the negative, Elepoo immediately and with great tact closed the negotiation by saying, "all shall be granted—it is settled—it is finished."[8]

The Qing government agreed to make Hong Kong Island a crown colony, ceding it to the Queen Victoria of Great Britain, in perpetuity[9] (常遠, Cháng yuǎn, in the Chinese version of the treaty), to provide British traders with a harbour where they could "careen and refit their ships and keep stores for that purpose" (Article III). Pottinger was later appointed the first Governor of Hong Kong.

In 1860, the colony was extended with the addition of the Kowloon peninsula under the Convention of Peking[10] and in 1898, the Second Convention of Peking further expanded the colony with the 99-year lease of the New Territories.[11] In 1984, the governments of the United Kingdom and the People's Republic of China (PRC) concluded the Sino-British Joint Declaration on the Question of Hong Kong, under which the sovereignty of the leased territories, together with Hong Kong Island and Kowloon (south of Boundary Street) ceded under the Convention of Peking (1860), was transferred to the PRC on 1 July 1997.[12]

Aftermath

The treaty was sealed by interpreter John Robert Morrison for the British and Wang Tajin for the Chinese. Harry Parkes, who was a student of Chinese under Morrison, gave his account of the ceremony:

There were four copies of the Treaty signed and sealed. They were bound in worked yellow silk, one Treaty in English and the same in Chinese stitched and bound together formed a copy. This being finished they all came out of the after-cabin and sat down to tiffin, and the different officers seated themselves all round the table, making plenty of guests. Almost directly after the Treaty was signed, a yellow flag for China at the main and a Union Jack for England at the mizen were hoisted, and at the same time a royal salute of twenty-one guns was fired.[13]

The Daoguang Emperor gave his assent for the treaty on 8 September.[4] After his assent arrived in Nanjing on 15 September, Pottinger's secretary George Alexander Malcolm was dispatched on board the steamer Auckland the next morning to the Court of St James's with a copy for ratification by Queen Victoria.[14] The emperor ratified the treaty on 27 October and Queen Victoria added her written assent on 28 December. Ratification was exchanged in Hong Kong on 26 June 1843.[4]

Pottinger wrote in a letter to the Earl of Aberdeen the following year that at a feast with Keying celebrating the ratification, Keying insisted they ceremonially exchange miniature portraits of each member of each other's families. Upon receiving a miniature portrait of Pottinger's wife, Pottinger wrote that Keying "placed [the miniature] on his head—which I am told is the highest token of respect and friendship—filled a glass of wine, held the picture in front of his face, muttered some words in a low voice, drank the wine, again placed the picture on his head and then sat down" to complete the ceremony of long-term amity between the two families and the two peoples.[15] This extravagant display has been analysed as showing an "erotically charged ... reciprocity [in] this symbolic gesture of swapping images of wives.[16]

Because of the brevity of the Treaty of Nanking and its terms being phrased only as general stipulations, the British and Chinese representatives agreed that a supplementary treaty should be concluded to establish more detailed regulations for relations. On 3 October 1843, the parties concluded the supplementary Treaty of the Bogue at the Bocca Tigris outside Canton.[citation needed]

Nevertheless, the treaties of 1842–43 left several unsettled issues. In particular they did not resolve the status of the opium traffic in favour of the British Empire. Although the Treaty of Wanghia with the Americans in 1844 explicitly banned Americans from selling opium, the trade continued as both the British and American merchants were only subject to the legal control of their permissive consuls. The opium traffic was later legalised in the Treaties of Tianjin, which China concluded after the Second Opium War resulted in another defeat for the Qing dynasty.[17]

The Treaty itself contained no provision for the legalization of the opium trade. Stephen R. Platt writes that such a term would have provided the opponents of Lord Palmerston, who headed the Conservative government that launched the war, with a seeming confirmation for their claim that the war was fought to support the opium trade.[18] Instead, Palmerston asked his negotiators to request the Chinese to legalize the sale of opium on their own initiative, outside of the treaty’s terms, which they refused.[18]

These treaties had deep and lasting effect. Nanking Treaty, together with the following treaties of 1843, 1858, and 1860, ended the Canton System as created in 1760. These treaties created a new framework for China's foreign relations and overseas trade, which would last for almost a hundred years and marked the start of what later nationalists called China's "century of humiliation." From the perspective of modern Chinese nationalists, the most injurious terms were the fixed trade tariff, extraterritoriality, the most favoured nation provisions and freeing the importation of British opium which continued to have social and economic consequences for the Chinese people. These terms were imposed by the British and extended to other Western powers with most favoured nation status, and were conceded by the ruling Qing dynasty in order to avert continued military defeats and under the hope that most favoured nation provision would set the foreigners against each other. Although China regained tariff autonomy in the 1920s, extraterritoriality was not formally abolished until the 1943 Sino-British Treaty for the Relinquishment of Extra-Territorial Rights in China.[19]

The stipulation of legal equality in diplomatic proceedings between Britain and China ended the centuries-long Sinocentric tributary system of interstate relations that placed China atop a formal hierarchy in its interactions with other states.[20] Despite this stipulation, the treaty's contents featured entirely concessions from the Chinese side with no reciprocity of provisions on the British side - for instance, Britain received the right to establish consulates in treaty ports that held the right to an audience with local officials, an option denied to China should it have hypothetically wanted to send its own formal diplomatic missions to Britain.[17] The one-sided nature of this treaty as a list of concessions, alongside the sovereignty ceded with the terms granting extraterritoriality and joint Sino-British determination of tariff, would earn the Nanking Treaty and similar settlements that followed the name, "unequal treaty," from Chinese nationalists in later centuries.[17]

Interestingly, Joanna Waley-Cohen writes that, at the time of its signing, the Qing did not regard the treaty as “of major significance.”[20] According to Waley-Cohen, the Treaty of Nanking’s terms remarkably resembled another treaty signed with the central Asian state of Kokand, which had also conflicted with the Qing over control of trade along Qing frontiers.[21] Failing to achieve results with a complete trade ban, the Qing arranged a treaty with Kokand that granted Kokandis “the right to live, trade, and levy taxes […] appoint consuls with extraterritorial jurisdiction over their compatriots in China,” alongside an indemnity.[21] The precedent set by the treaty with Kokand made the Nanking Treaty palpable enough that the Qing did not immediately regard this settlement as a disastrous capitulation.

A copy of the treaty is kept by the British government while another copy is kept by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Republic of China at the National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan.[22]

See also

- Western imperialism in Asia

- History of Hong Kong

- Anglo-Chinese relations

- Henry Collen (photographed the treaty)

- David Sassoon

- Treaty of Chushul

Further reading

- Fairbank, J. K. (1940). "Chinese Diplomacy and the Treaty of Nanking, 1842". The Journal of Modern History. 12 (1): 1–30.

Notes

- ^ Mayers, William Frederick (1902). Treaties Between the Empire of China and Foreign Powers (4th ed.). Shanghai: North-China Herald, London (1871)ld. p. 1.

- ^ Lovell, Julia (20 December 2012). The Opium War Ya pian zhan zheng: drugs, dreams and the making of China. London: Picador. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-330-45748-4.

- ^ Ha-Joon Chang, "Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism," (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2008), p. 24

- ^ a b c Wood, R. Derek (May 1996). "The Treaty of Nanking: Form and the Foreign Office, 1842–43". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History

- ^ John Darwin, After Tamerlane: The Global History of Empire, p. 271. (London: Allen Lane, 2007) "Under the 1842 Treaty of Nanking, five 'treaty ports' were opened to Western trade, Hong Kong island was ceded to the British, the Europeans were allowed to station consuls in the open ports, and the old Canton system was replaced by the freedom to trade and the promise that no more than 5 per cent duty would be charged on foreign imports."

- ^ John Darwin, After Tamerlane: The Global History of Empire, p. 431. (London: Allen Lane, 2007) "In 1943 the remnants of China's unequal treaties were at last swept away when the British abandoned their surviving privileges there as so much useless lumber."

- ^ a b c d Treaty of Nanking

- ^ a b Martin, Robert Montgomery (1847). China: Political, Commercial, and Social; In an Official Report to Her Majesty's Government. Volume 2. London: James Madden. p. 84.

- ^ Treaty of Nanking, 29 August 1842,

His Majesty the Emperor of China cedes to Her Majesty the Queen of Great Britain, &c., the Island of Hong-Kong, to be possessed in perpetuity by Her Britannic Majesty, Her Heirs and Successors, and to be governed by such Laws and Regulations as Her Majesty the Queen of Great Britain, &c., shall see fit to direct.

- ^ Endacott, G. B.; Carroll, John M. (2005) [1962]. A biographical sketch-book of early Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-962-209-742-1.

- ^ "Lessons in History". National Palace Museum (Taipei). 9 August 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ^ Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau, The Government of the HKSAR. "The Joint Declaration" and following pages, 1 July 2007.

- ^ Lane-Poole, Stanley (1894). The Life of Sir Harry Parkes. Volume 1. London: Macmillan and Co. pp. 47–48.

- ^ The Chinese Repository. Volume 11. Canton. 1842. p. 680.

- ^ Koon, Yeewan (2012). "The Face of Diplomacy in 19th-Century China: Qiying's Portrait Gifts". In Johnson, Kendall (ed.). Narratives of Free Trade: The Commercial Cultures of Early US-China Relations. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 131–148.

- ^ Koon, Yeewan (2012). "The Face of Diplomacy in 19th-Century China: Qiying's Portrait Gifts". In Johnson, Kendall (ed.). Narratives of Free Trade: The Commercial Cultures of Early US-China Relations. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 139–140.

- ^ a b c Platt, Stephen R. (2022). Wasserstrom, Jeffrey N. (ed.). The Oxford history of modern China. Oxford histories (3rd ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom ; New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-19-289520-2. OCLC 1260821193.

- ^ a b Platt, Stephen R. (2018). Imperial twilight: the Opium War and the End of China's Last Golden Age (1st ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 555–556. ISBN 978-0-307-96173-0.

- ^ Hsu, The Rise of Modern China: 190–192.

- ^ a b Waley-Cohen, Joanna (2000). The sextants of Beijing: global currents in Chinese history (1st ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-393-32051-0.

- ^ a b Waley-Cohen, Joanna (2000). The sextants of Beijing: global currents in Chinese history (1st ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-393-32051-0.

- ^ Liu, Kwangyin (9 August 2011). "National Palace Museum displays ROC diplomatic archives". Taiwan Today. p. 1. Archived from the original on 16 September 2023. Retrieved 15 September 2023.

References

- Fairbank, John King. Trade and Diplomacy on the China Coast: The Opening of the Treaty Ports, 1842–1854. 2 vols. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1953.

- Têng Ssu-yü. Chang Hsi and the Treaty of Nanking, 1842. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1944.

- R. Derek Wood, 'The Treaty of Nanking: Form and the Foreign Office, 1842–1843', Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History (London) 24 (May 1996), 181–196 online.

External links

- Original Treaty of Nanking in English-Chinese Archived 14 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine from National Palace Museum, Taipei

- English Text in London Gazette (Differs in some respects from Chinese text)