NASA Astronaut Group 8

| TFNG (Thirty-Five New Guys) | |

|---|---|

Official group portrait | |

| Year selected | 1978 |

| Number selected | 35 |

NASA Astronaut Group 8 was a group of 35 astronauts announced on January 16, 1978. It was the first NASA selection since Group 6 in 1967, and was the largest group to that date. The class was the first to include female and minority astronauts; of the 35 selected, six were women, one of them being Jewish American, three were African American, and one was Asian American. Due to the long delay between the last Apollo lunar mission in 1972 and the first flight of the Space Shuttle in 1981, few astronauts from the older groups remained, and they were outnumbered by the newcomers, who became known as the Thirty-Five New Guys (TFNG). Since then, a new group of candidates has been selected roughly every two years.

In Astronaut Group 8, two different kinds of astronaut were selected: pilots and mission specialists. The group consisted of 15 pilots, all test pilots, and 20 mission specialists. NASA stopped sending non-pilots for one year of pilot training. It also ceased appointing astronauts on selection. Instead, starting with this group, new selections were considered astronaut candidates rather than fully-fledged astronauts until they finished their training.

Four members of this group, Dick Scobee, Judith Resnik, Ellison Onizuka, and Ronald McNair, died in the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster. These four, plus Shannon Lucid, received the Congressional Space Medal of Honor, giving this astronaut class five total recipients of this top NASA award. This is second only to the New Nine class of 1962, which received seven. The careers of the TFNGs would span the entire Space Shuttle Program. They reshaped the image of the American astronaut into one that more closely resembled the diversity of American society, and opened the doors for others that would follow.

Background

Equal employment opportunity at NASA

The enactment of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 gave teeth to the promise of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to address the persistent and entrenched employment discrimination against women, African Americans and other minority groups in American society.[1] Specifically, it empowered the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to take enforcement action against individuals, employers, and labor unions that violated the employment provisions of the 1964 Act, and expanded the jurisdiction of the commission to deal with them.[2] It also extended the scope of affirmative action, mandating that all executive branch agencies also comply with the act.[3] Supporters of the legislation hoped that it would spur social change, but culture was not so easily changed. Women in science and engineering still found the culture off-putting, and while colleges dramatically increased their enrollment of women in these fields, many women found themselves in classrooms mostly filled with men, some of whom were openly hostile to their presence.[1] Although in the early 1970s women received 40 percent of the PhDs awarded in biology, they represented just 4 percent of those in engineering; the 10 percent mark was not reached until the 1990s, by which time African Americans were awarded 2 percent of doctorates in all fields of science and engineering.[4]

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was no paragon of diversity in 1972. Most of its twelve major facilities were located in the southern United States.[5] Eight of them had created equal employment/affirmative action offices, but the staff of six of them was entirely white.[6] In 1971, the Administrator of NASA, James C. Fletcher, appointed Ruth Bates Harris, an African-American, as NASA's Director of Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO),[4] but before she commenced work on 4 October 1971, Fletcher demoted her to deputy director, and reduced her responsibility to dealing with contractors only.[6] In 1973, 5.6 percent of NASA staff were minorities, and 18 percent were women at a time when the United States federal civil service averages were 20 and 34 percent respectively. Although NASA employed 4,432 women, only 310 were in science and engineering, of which just four were in the top grades, counting Harris. Although it could be argued that women and minorities were under-represented in the aerospace engineering industry as a whole, NASA was no better at recruiting women as lawyers than as scientists, and while minorities were well represented in the ranks of NASA's janitors (69 percent), it employed no women to perform this work.[7] The Kennedy Space Center had 43 grades of secretaries so women could be promoted without reaching management levels.[7]

Harris soon proved a feisty and forceful presence who was unafraid to ask uncomfortable questions. After reading a newspaper report that Wernher von Braun had used slave labor to build his rockets during World War II, she asked him if it was true.[8] She wanted her original job back,[7] and civil service rules required that affirmative action directors report directly to the administrators of government agencies.[8] To fill the position, NASA's deputy administrator, George Low, appointed Dudley McConnell, NASA's most senior African-American engineer to the position, with Harris as one of his deputies.[9] Harris, Samuel Lynn (a former Tuskegee airman) and Joseph M. Hogan prepared a report on the state of equal opportunity in NASA on their own time, and submitted it directly to Fletcher.[7] The report concluded:

NASA has demonstrated to the world that it has limitless imagination, vision, capability, courage and faith, limitless persistence and infinite space potential. It made the United States a winner in space and improved the quality of life for all people. ... However, in spite of sincere efforts on the part of some NASA management and employees, human rights in NASA have not even gotten off the ground. In fact, Equal Opportunity is a sham in NASA.[10]

Fletcher fired Harris, transferred Hogan, and gave Lynn a stern warning. To the surprise of Fletcher and Low, Harris's firing generated a storm of negative coverage in the media.[11][12][9] Seventy NASA employees protested the decision, and NAACP Legal Defense Fund lawyers petitioned the United States Civil Service Commission to rule Harris's dismissal as an unlawful reprisal. NASA's legal counsel advised Fletcher to settle. The United States Senate Committee on Appropriations wanted for an explanation, and Senator William Proxmire grilled McConnell. Aides urged Fletcher to appear before the United States Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences. Fletcher demurred; he was a Mormon, and his church practised racial exclusion until 1978, so he sent the Jewish Low in his place in January 1974. Low urged McConnell to hire Harriet G. Jenkins as his deputy, and when he resisted, Low had Fletcher hire her.[13] In August 1974, Harris was re-hired, but in a new role in community outreach and public relations,[14] and she left NASA in 1976. Jenkins replaced McConnell,[15] and would hold down the position until 1992. Great changes would occur on her watch.[16]

Preparing for the Space Shuttle

Harris noted that one issue that came up constantly was that of when the all-white, all-male NASA Astronaut Corps would recruit its first woman or a minority astronaut. In a July 19, 1972, memorandum to Ted Groo, the Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight, she urged that this be rectified as a matter of urgency.[17] NASA's directors agreed in September 1972 on the need for a plan to be drawn up defining the schedule and requirements for crewing the Space Shuttle, but it was not expected to fly before 1978, and NASA already had sufficient astronauts to carry out scheduled missions and the proposed early Space Shuttle flights too, so no new astronauts would be required before 1982. Assuming twenty months between a call for applications and an individual's first flight, it was estimated NASA would not need to initiate an astronaut recruitment process before 1980.[18]

Planning proceeded on the make up of a Space Shuttle crew. By 1972, five roles were envisaged:

- Commander (CDR), an astronaut who would be responsible for flying the spacecraft, and for all aspects of the mission;

- Pilot (PLT), a co-pilot, an astronaut who would be a deputy to the commander;

- Mission specialist (MS), astronauts who would perform other duties related to the operation of the spacecraft, of which there might be more than one per mission;

- Payload specialist (PS), a non-astronaut with expertise in the spacecraft's payload; and

- Passenger, a non-astronaut present as an uninvolved observer.[19]

Although the payload specialist and passengers would not be astronauts, it was expected that they would have to undergo some astronaut training for safety purposes. An early decision was that mission specialist astronauts would not be required to undergo pilot training, which had been required of the scientist astronauts selected in NASA Astronaut Group 4 in 1965 and NASA Astronaut Group 6 in 1967.[19] The inclusion of a space toilet in the Space Shuttle design permitted a degree of privacy impossible in the Gemini and Apollo spacecraft. This encouraged NASA management to believe that women could fly in space without offending contemporary American social and cultural mores regarding sexuality and hygiene, which might have caused embarrassment to the agency.[20]

Recruitment

Selection board

A comprehensive recruitment plan for pilots was drawn up in 1974, and for mission specialists the following year, but specific provisions to recruit women and minorities were not completed until early 1976. The Director of the Johnson Space Center (JSC), Christopher C. Kraft Jr., created an Astronaut Selection Board on March 12, 1976, and it held its first meeting on March 24.[21] The makeup of the board was:

- Chairman

- George Abbey, Director of Flight Crew Operations, JSC

- Recorder

- Jay F. Honeycutt, Assistant to the Director of the JSC

- Pilot Panel

- John W. Young, astronaut, Chief of the Astronaut Office

- Vance Brand, astronaut

- Martin L. Raines, Director of Safety, Reliability and Quality Assurance

- Joseph D. Atkinson, Chief of the Equal Opportunity Programs Office, JSC

- Jack R. Lister, Personnel Office, JSC

- Donald K. Slayton, astronaut, Manager of Approach and Landing Tests, JSC

- Mission Specialist Panel

- Joseph Kerwin, astronaut, Chief of the Mission Specialist Group, Astronaut Office, JSC

- Robert A. Parker, astronaut

- Edward Gibson, astronaut

- Carolyn Huntoon, Chief of Metabolism and Biochemistry Branch, JSC

- Joseph D. Atkinson, Chief of the Equal Opportunity Programs Office, JSC

- Jack R. Lister, Personnel Office, JSC

- James Trainor, Associate Chief of the High Energy Physics Laboratory, Goddard Space Flight Center

- Robert Piland, Associate Director for Program Development, JSC[22][23]

By this time it had been nearly ten years since NASA had last conducted an astronaut selection process in June 1967; NASA Astronaut Group 7 had transferred from the United States Air Force's Manned Orbiting Laboratory in June 1969 without one.[24] The presence of Huntoon, a white woman, and Atkinson, a black man, meant that this was the first time people other than white men had served on a NASA astronaut selection board.[25]

Call for applications

On July 8, 1976, NASA issued a call for applications for at least 15 pilot candidates and 15 mission specialist candidates. For the first time, new selections would be considered astronaut candidates rather than fully-fledged astronauts until they finished training and evaluation, which was expected to take two years. Pilot candidate applicants had to have at least a bachelor's degree in engineering, a physical science or mathematics from an accredited institution, although an advanced degree was desirable, and at least 1,000 hours of pilot flying time, preferably in high performance jet aircraft, but 2,000 hours was desirable. They had to pass a NASA Class 1 physical examination, and a height between 64 and 76 inches (160 and 190 cm) was desirable. For mission specialist candidates, the academic degree could also be in the biological sciences, only a NASA class 2 physical was required, no pilot experience was necessary, and the minimum desirable height was 60 inches (150 cm).[26] The main difference between the two physical classes was that glasses were acceptable for the class 2 physical, if eyesight was 20/20 when corrected.[27]

Military personnel would have to forward applications through their service departments. They would be seconded to NASA, and would receive their usual pay and allowances. Civilians astronaut candidates could apply directly. Their pay was set at Federal government General Schedule grades 7 to 15, depending on achievements and academic experience, with salaries ranging from around $11,000 to $34,000 (equivalent to $59,000 to $182,000 in 2023). Minorities and women were encouraged to apply. The deadline for applications was June 30, 1977, with training expected to commence on July 1, 1978.[26]

NASA management were certain that there were highly qualified women and minorities out there, but they needed to persuade them to apply. A special team consisting of Mary Wilmarth and Baley Davis from the JSC Personnel Office, and Joseph D. Atkinson and Jose R. Perez from the JSC Equal Opportunity Programs Office was created to publicize the recruitment effort. NASA centers and NASA contractors were canvassed for prospective applicants, minority and women's professional organizations were contacted, and graduated schools and government agencies were asked to notify their students and employees. Political organizations like the Congressional Black Caucus and NAACP were contacted. Advertisements were placed in minority magazines with minority readership like Ebony, Black Enterprise, Essence and Jet. Nichelle Nichols, an African-American actor best known for the television series Star Trek was hired to do spot advertising.[28] Her publicity firm, Women in Motion, was paid $49,000 ($equivalent to $262,000 in 2023). She met with members of community organizations, colleges and institutions to familiarize them with the requirements for Space Shuttle astronaut candidates.[29]

Unlike previous calls for applications, the 1976 one did not specify a requirement for citizenship of the United States. This was because on June 1, 1976, the Supreme Court had ruled in the case of Hampton v. Mow Sun Wong that the Civil Service Commission could not issue regulations prohibiting the employment of non-citizens. It however, left the door open to their prohibition through statute or executive order. On September 2, 1976, President Gerald Ford issued Executive Order 11935, requiring citizenship for Federal employment, thereby effectively nullifying the Supreme Court's ruling. Some applications were received from non-citizens. On December 7, 1976, NASA's Director of Personnel, Carl Grant, advised the selection board that any applications accepted from non-citizens should be on the understanding that they would take up US citizenship before the end of the two-year training and evaluation period.[30]

Selection process

Between July 1976 and June 1977, the JSC received 24,618 inquiries. Of these 20,440 requested and were sent application packages.[31] Eventually, the total number of applications was 8,079. Most were received in the final two weeks before the deadline date. It was not possible for the selection board to evaluate this many applications, so they were pre-screened to identify the most promising ones. The first pass was to eliminate those that did not meet the minimum requirements.[32] This eliminated over 2,000 applications. The selection board then began processing the remaining 5,680.[33] A point system was then used to rank candidates. For pilots, this took account of hours flown, test pilot experience, types and numbers of different aircraft flown, and grade point average for undergraduate and graduate degrees. For mission specialists, points were awarded for academic degrees, grade point averages, and years of experience.[34]

The selection board assessed 649 of the pilot applicants as qualified. Of these, 147 were military and 512 were civilians; ten were minorities and eight were women. From these, 80 were selected for interviews, of whom 76 were military and four were civilians; three were minorities but there were no women.[23] The first woman to graduate from the United States Naval Test Pilot School, Beth Hubert, did not do so until 1985,[35] and the first to graduate from the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School, Jane Holley, in 1974.[36]

Of the mission specialist applicants, 5,680 were regarded as qualified. Of these, 161 were military, six of whom were minorities and three of whom were women. The other 5,519 were civilians. Of these, 332 were minorities and 1,248 were women. The selection board reduced the number of applicants to 208, of which 80 were pilot applicants and 128 were the mission specialist applicants. Of the pilot applicants, 76 were from the military and four were civilians; three of the military applicants were minorities. Of the 128 mission specialist applicants, 45 were from the military, four of whom were minorities and two were women, and 83 were civilians, of whom four were minorities and twelve were women.[23]

The 208 applicants were divided into ten groups of about twenty, and called in to the JSC for interviews and medical tests. The latter were conducted under the supervision of Sam L. Pool, the chief of the Medical services Division at JSC. On April 1, 1977, twenty volunteers were run through the medical selection to work out the procedures and logistics of it. The tests involved 24 procedures, including a general examination by a flight surgeon. The candidate's medical history was examined, and psychological, psychiatric, ophthalmological, neurological, dental, musculoskeletal and eye, nose and throat examinations were conducted. Tests were conducted using a rotating chair to test susceptibility to motion sickness, on a treadmill to measure heart rate, and with a Personal Rescue Enclosure to test for claustrophobia.[37] The psychiatric process was not free of gender bias; one consultant was later found to have rejected 40 percent of female applicants in the 1978, 1980, 1984 and 1985 selections but only 7 percent of male ones.[38] Applicants were put up at the Kings Inn Ramada in Clear Lake, Texas, where an evening reception and pre-interview briefing was held. The medical tests eliminated 56 applicants, and three more indicated that they did not wish to proceed. That left 149 applicants (74 pilots and 75 mission specialists) who were listed.[37]

From this group, the selection board nominated 20 pilot and 20 mission specialist astronaut candidates. However, in November 1977, NASA Administrator Robert A. Frosch noted that NASA had enough pilot astronauts, and instructed Abbey to reduce the numbers to 15. All five of those dropped at the last minute would later be selected with NASA Astronaut Group 9 in 1980.[39] In all, six of finalists who were passed over in 1978 would later qualify as pilot astronaut candidates in 1980: John Blaha, Roy Bridges, Guy Gardner, Ronald Grabe, Bryan O'Connor, and Richard Richards as pilots, and six as mission specialists: James Bagian, Bonnie Dunbar, Bill Fisher, John Lounge, Jerry Ross and Robert Springer.[40] Another unsuccessful finalist, John Casper, would be selected with NASA Astronaut Group 10 in 1984.[41] Two others who were not selected would eventually fly in space as payload specialists: Millie Hughes-Fulford and Byron Lichtenberg.[42]

On January 16, 1978, Abbey contacted the 35 successful applicants and notified them of their selection, and asked them to confirm that they still wanted the job. Three were outside the United States; Kathy Sullivan was in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, working on her PhD; Steven Hawley was doing post-doctoral research in Chile, and David Walker was serving on the aircraft carrier USS America in the Mediterranean Sea.[40] The names of the 35 were then publicly released.[23]

Group members

Pilots

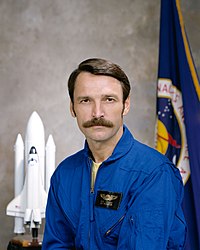

| Image | Name | Born | Died | Career | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Daniel C. Brandenstein | Watertown, Wisconsin, U.S. January 17, 1943 |

Brandenstein graduated from Watertown High School in 1961, earned a Bachelor of Science degree in mathematics and physics from the University of Wisconsin–River Falls in 1965, and joined the U.S. Navy. He became a naval aviator and flew 192 combat mission in two deployments to Southeast Asia flying Grumman A-6 Intruder with Attack Squadron 196 (VA-196) from the aircraft carriers USS Constellation and USS Ranger. He graduated from the U.S. Naval Test Pilot School at NAS Patuxent River, Maryland, with class 59 in October 1971, along with Frederick Hauck. He flew in space four times:

He was Chief of the Astronaut Office from April 1987 to September 1992, and retired from NASA and the U.S. Navy on October 1, 1992. |

[43][44][45] | |

|

Michael L. Coats | Sacramento, California, U.S. January 16, 1946 |

Coats graduated from Ramona High School in Riverside, California, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree from the United States Naval Academy in 1968, a Master of Science degree in Administration of Science and Technology from George Washington University in 1977, and a Master of Science degree in Aeronautical Engineering from the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School in 1979. He flew 315 combat missions in Southeast Asia flying the LTV A-7 Corsair II with Attack Squadron 192 (VA-192) from the aircraft carrier USS Kitty Hawk (CV-63) between August 1970 and September 1972. He graduated the U.S. Naval Test Pilot School at NAS Patuxent River, Maryland, in November 1974 with Class 66 along with Group 9 astronaut Michael J. Smith, and served as an instructor there from April 1976 to May 1977. He flew in space three times:

He was Acting Chief of the Astronaut Office from May 1989 to March 1990, and retired from NASA and the U.S. Navy on August 1, 1992. |

[46][47][48] | |

|

Richard O. Covey | Fayetteville, Arkansas, U.S. August 1, 1946 |

Covey graduated from Choctawhatchee High School in Shalimar, Florida, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in engineering science with a major in astronautical engineering from the United States Air Force Academy in 1968, and a Master of Science degree in Aeronautics and Astronautics from Purdue University in 1969. He flew 339 combat missions in Southeast Asia, and graduated the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School in 1975 with class 74B, along with Elison Onizuka and Jane Holley. He flew in space four times:

He retired from NASA on July 11, 1994, and from the U.S. Navy on August 1, 1994. |

[49][50][36] | |

|

John O. Creighton | Orange, Texas, U.S. April 28, 1943 |

Creighton graduated from Ballard High School in Seattle, Washington, earned a Bachelor of Science degree from the United States Naval Academy in 1966 and a Master of Science degree in Administration of Science and Technology from George Washington University in 1978. He flew 175 combat missions in Southeast Asia flying the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II with Fighter Squadron 154 (VF-154) during two combat deployments between July 1968 and May 1970 aboard the aircraft carrier USS Ranger. He attended the U.S. Naval Test Pilot School at NAS Patuxent River, Maryland, from June 1970 to February 1971. He flew in space three times:

He retired from NASA and the U.S. Navy on July 15, 1992. |

[51][36][52] | |

|

Robert L. Gibson | Cooperstown, New York, U.S. October 30, 1946 |

"Hoot" Gibson graduated from Huntington High School in Huntington, New York, in 1964 earned an Associate degree in Engineering Science from Suffolk County Community College in 1966. He received a Bachelor of Science degree in Aeronautical Engineering from California Polytechnic State University in 1969. Between April 1972 and September 1975, he flew combat missions in Southeast Asia with Fighter Squadron 111 (VF-111) and Fighter Squadron 1 (VF-1) aboard the aircraft carriers USS Coral Sea and USS Enterprise, and was a graduate of the Naval Fighter Weapons School, popularly known as "Topgun". He graduated from the U.S. Naval Test Pilot School at NAS Patuxent River in June 1977. He flew in space five times:

He was Chief of the Astronaut Office from December 1992 to September 1994. He retired from the U.S. Navy in June 1996, and from NASA and November 1996. |

[53][54] | |

|

Frederick D. Gregory | Washington, D.C., U.S. January 7, 1941 |

Gregory from Anacostia High School in Washington, D.C., in 1958, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree from the United States Air Force Academy in 1964, and a master's degree in information systems from George Washington University in 1977. He flew 550 combat mission in Vietnam as a helicopter rescue pilot flying the Kaman HH-43 Huskie from Da Nang Air Base, and attended the United States Naval Test Pilot School at NAS Patuxent River, Maryland, with Class 58 from September 1970 to June 1971. In June 1974, he was posted to the NASA's Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, as a test pilot. He flew in space three times:

Gregory served at NASA Headquarters as Associate Administrator for the Office of Safety and MissionAssurance from 1992 to 2001, as Associate Administrator for the Office of Space Flight from 2001 to 2002, and as NASA Deputy Administrator from 2002 to 2005, becoming the first African-American to hold this position. He resigned from NASA in October 2005 |

[55][56] | |

|

S. David Griggs | Portland, Oregon, U.S. September 7, 1939 |

June 17, 1989 | Griggs graduated from Lincoln High School in Portland, Oregon, in 1957, earned a Bachelor of Science degree from the United States Naval Academy in 1962, and a Master of Science degree in administration from George Washington University in 1970. He completed two operational cruises in Southeast Asia with Attack Squadron 72 flying Douglas A-4 Skyhawk aircraft aboard the aircraft carriers USS Independence and USS Franklin D. Roosevelt, and attended the United States Naval Test Pilot School at NAS Patuxent River, Maryland, in 1967. He retired from active duty in 1970, and joined the JSC as a test pilot. He flew in space only once. He was assigned as pilot for STS-33, but was killed in an aircraft accident several months before the launch.

|

[57] |

|

Frederick H. Hauck | Long Beach, California, U.S. April 11, 1941 |

Hauck graduated from St. Albans School in Washington, D.C., in 1958, earned a Bachelor of Science in degree in physics from Tufts University in 1962 and a Master of Science degree in nuclear engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1966. He flew 114 combat missions in Southeast Asia with Attack Squadron 35 (VA-35) aboard the aircraft carrier USS Coral Sea, and graduated from U.S. Naval Test Pilot School in 1971 with Class 59, which also included Daniel Brandenstein.

He flew in space three times:

In May 1989, he returned to the Navy as Director of the Navy Space Systems Division, in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. He retired from active duty on June 1, 1990. |

[58][59] | |

|

Jon McBride | Charleston, West Virginia, U.S. August 14, 1943 |

August 7, 2024 | McBride graduated from Woodrow Wilson High School in Beckley, West Virginia, attended West Virginia University from 1960 to 1964, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in aeronautical engineering from the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School in 1971. He flew 64 combat missions in Southeast Asia, and graduated from the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in California with class 75A in December 1975 along with Guy Gardner, Steven Nagel and Loren Shriver. He flew in space only once:

McBride was scheduled to fly again as commander of STS-61-E in March 1986, but the mission was cancelled in the wake of the January 1986 Space Shuttle Challenger disaster. On July 30, 1987, he was assigned to NASA Headquarters to serve as Assistant Administrator for Congressional Relations. He held this post from September 1987 until March 1989. He was named as commander of the STS-35 (ASTRO-1) mission scheduled for March 1990, but he retired from NASA and the Navy in May 1989 before it was flown. |

[60][61] |

|

Steven R. Nagel | Canton, Illinois, U.S. October 27, 1946 |

August 21, 2014 | Nagel graduated from Canton High School, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in aerospace engineering from the University of Illinois in 1969 and a Master of Science degree in mechanical engineering from California State University, Fresno, in 1978. He served a one-year tour of duty as a flight instructor in Thailand, and graduated from the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base with class 75A in December 1975 along with Guy Gardner, Jon McBride and Loren Shriver.

He flew in space four times:

Nagel retired from the Air Force on February 28, 1995, and from the Astronaut Office on March 1, 1995, to assume the full-time position of deputy director for operations development, Safety, Reliability, and Quality Assurance Office at the Johnson Space Center. In September 1996, he transferred to the Aircraft Operations Division as a research pilot, chief of aviation safety and deputy division chief. He retired from NASA on May 31, 2011 |

[62][59] |

|

Francis R. Scobee | Cle Elum, Washington, U.S. May 19, 1939 |

January 28, 1986 | Scobee graduated from Auburn High School in Auburn, Washington, in 1957, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in aerospace engineering from the University of Arizona in 1965. He completed a combat tour in Vietnam, and graduated from the U.S. Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in California with class 71B in 1972. He then flew the Martin Marietta X-24, an experimental aircraft designed to test the concept of unpowered reentry and landing later used by the Space Shuttle. He flew in space once:

On his second mission, he died in the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster:

| |

|

Brewster H. Shaw Jr. | Cass City, Michigan, U.S. May 16, 1945 |

Shaw graduated from Cass City High School in 1963, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in engineering mechanics from the University of Wisconsin in 1968, and a Master of Science degree in engineering mechanics from the University of Wisconsin in 1969. He graduated from the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base with class 75B, the same class as Mike Mullane and Jerry Ross. He flew in space three times:

He left JSC in October 1989 to become the head of Space Shuttle Operations at KSC. He subsequently became the deputy program manager for the Space Shuttle, and Director of Space Shuttle Operations. He left NASA in 1996. |

[65][66] | |

|

Loren J. Shriver | Jefferson, Iowa, U.S. September 23, 1944 |

Shriver graduated Paton Consolidated High School in Paton, Iowa, and from the United States Air Force Academy with the class of 1967. He graduated from the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in December 1975 with class 75A, the same class as Guy Gardner, Jon McBride and Steven Nagel. He flew in space three times:

In 1993 he left JSC and became the Space Shuttle Program Manager, Launch Integration, at KSC. He was Deputy Director for Launch and Payload Processing there from 1997 to 2000, and the Deputy Program Manager of the Space Shuttle Program from 2000 to 2006. He retired NASA and from the USAF as a colonel in 2006. |

[23][67][68] | |

|

David M. Walker | Columbus, Georgia, U.S. May 20, 1944 |

April 23, 2001 | Walker graduated Eustis High School in Eustis, Florida, in 1962, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree from the United States Naval Academy in 1966. He attended the U.S. Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, California, from December 1970 to 1971 with class 71A, and in January 1972 became an experimental and engineering test pilot in the flight test division at the Naval Air Test Center, NAS Patuxent River, Maryland. He flew in space four times:

He left NASA and the Navy on April 15, 1996. |

[69][70][71] |

|

Donald E. Williams | Lafayette, Indiana, U.S. February 13, 1942 |

February 23, 2016 | Williams graduated from Otterbein High School in Otterbein, Indiana, in 1960, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in mechanical engineering from Purdue University in 1964, and was commissioned in the US Navy through the NROTC program at Purdue. He made two deployments to Vietnam aboard the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise flying Douglas A-4 Skyhawk aircraft with Attack Squadron 113 (VA-113), and two more aboard the USS Enterprise flying the LTV A-7 Corsair II with Carrier Air Wing Fourteen and Attack Squadron 97 (VA-97), for a total of 330 combat missions. He graduated from the U.S. Naval Test Pilot School at NAS Patuxent River, Maryland, with class 65 in June 1974. He flew in space twice:

He was the Deputy Manager, Operations Integration, National Space Transportation System Program Office at JSC from September 1982 until July 1983, Deputy Chief of the Aircraft Operations Division at JSC from July 1985 toAugust 1986, and Chief of the Mission Support Branch of the Astronaut Office from September 1986 to December 1988. He retired from NASA and the US Navy with the rank of captain in March 1990. |

[72][73][74] |

Mission specialists

| Image | Name | Born | Died | Career | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Guion S. Bluford Jr. | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. November 22, 1942 |

Bluford graduated from Overbrook High School in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1960. He earned a Bachelor of Science degree in aerospace engineering from the Pennsylvania State University in 1964, a Master of Science degree in aerospace engineering from the Air Force Institute of Technology in 1974, a Doctor of Philosophy in aerospace engineering with a minor in laser physics from the Air Force Institute of Technology in 1978, and a Master of Business Administration from the University of Houston–Clear Lake in 1987. He was commissioned in the United States Air Force through the Air Force ROTC at Pennsylvania State University. He flew 144 combat missions in the Vietnam War, flying the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II with the 557th Tactical Fighter Squadron at Cam Ranh Bay Air Base. He flew in space four times:

He retired from NASA and the Air Force in July 1993. |

[75][76][77] | |

|

James F. Buchli | New Rockford, North Dakota, U.S. June 20, 1945 |

Buchli graduated from Fargo Central High School in Fargo, North Dakota, in 1963. He earned a Bachelor of Science degree in aeronautical engineering from the United States Naval Academy in 1967 and a Master of Science degree in aeronautical engineering systems from the University of West Florida in 1975. He was commissioned in the United States Marine Corps on graduation from the Naval Academy, and performed a tour of duty in Vietnam as a platoon commander in the 9th Marine Regiment and a company commander in the 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion. He then underwent Naval Flight Officer training and was assigned to Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 122 (VMFA-122). In 1977, he was assigned to the U.S. Naval Test Pilot School at Patuxent River, Maryland. He flew in space four times:

He served as Deputy Chief of the Astronaut Office from March 1989 until May 1992. He retired from the U.S. Marine Corps and NASA on September 1, 1992. |

[78] | |

|

John M. Fabian | Goose Creek, Texas, U.S. January 28, 1939 |

Fabian graduated from Pullman High School in Pullman, Washington, in 1957. He earned a Bachelor of Science degree in mechanical engineering from Washington State University in 1962, a Master of Science degree in aerospace engineering from the Air Force Institute of Technology in 1964, and a PhD in aeronautics and astronautics from the University of Washington in 1974. He was commissioned in the United States Air Force (USAF) through the Air Force ROTC at Washington State University, and flew 90 combat missions in Southeast Asia as a Boeing KC-135 Stratotanker pilot. He flew in space twice:

He was scheduled to fly again in May 1986 on STS-61-G, but he announced his intention to resign in September 1985, and was replaced by Norman Thagard. Fabian left NASA on January 1, 1986, and returned to the USAF as the Director of Space in the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff of the Air Force, Plans and Operations. He retired from the USAF as a colonel in June 1987. |

[79][80] | |

|

Anna L. Fisher | St. Albans, Queens, New York, U.S. August 24, 1949 |

Fisher graduated from San Pedro High School in San Pedro, California, in 1967, and earned a Bachelor of Science in Chemistry from the University of California, Los Angeles, (UCLA) in 1971, a Doctor of Medicine from UCLA in 1976, and a Master of Science in chemistry from UCLA in 1987. Fisher flew in space only once:

She was assigned as a mission specialist on the STS-61-H that was scheduled to fly 1986, but the mission was cancelled in the aftermath of the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster. In 1989, she took a leave of absence from the Astronaut Office to raise her family. She returned in January 1996, and was Chief of the Space Station branch from 1996 to 2002. From January 2011 until August 2013, she served as an ISS Capsule Communicator (CAPCOM) in the Mission Control Center. She retired from NASA on April 28, 2017. |

[81][82] | |

|

Dale A. Gardner | Fairmont, Minnesota, U.S. November 8, 1948 |

February 19, 2014 | Gardner graduated as valedictorian of his class at Savanna Community High School in Savanna, Illinois, in 1966, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in engineering physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign in 1970. He joined the Navy after graduation and became a Naval Flight Officer. While at the Naval Air Test Center at NAS Patuxent River, Maryland, from May 1971 to July 1973, he was involved in the development of the Grumman F-14 Tomcat, which he later flew with Fighter Squadron 1 (VF-1) from the USS Enterprise. He flew in space twice:

Gardner returned to the Navy in 1986, and was assigned to the U.S. Space Command at Cheyenne Mountain Air Force Base in Colorado Springs, Colorado, where he was Deputy Chief of the Space Control Operations Division. He was promoted to captain in June 1989, became Space Command's Deputy Director for Space Control at Peterson Air Force Base. He retired from the Navy in October 1990 |

[83][84] |

|

Terry J. Hart | Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. October 27, 1946 |

Hart graduated from Mt. Lebanon High School in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1964, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in mechanical engineering from Lehigh University in 1968, a Master of Science degree in mechanical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1969, and a Master of Science in electrical engineering from Rutgers University in 1978. He was on active duty with the USAF from 1969 to 1973, when he joined the New Jersey Air National Guard. He flew in space once:

Hart was offered a second space flight on STS-61-A, but turned it down. He was only on a leave of absence from Bell Telephone Laboratories, and with the breakup of the Bell System he was asked to return. He left NASA on June 15, 1984, and retired from the Air National Guard in 1990. |

[85][86][87] | |

|

Steven A. Hawley | Ottawa, Kansas, U.S. December 12, 1951 |

Hawley graduated from Salina High School Central in Salina, Kansas, in 1969, and earned Bachelor of Arts degrees in physics and astronomy from the University of Kansas in 1973, and a PhD in astronomy and astrophysics from the University of California, Santa Cruz in 1977. He flew in space five times:

He was Technical Assistant to the Director of Flight Crew Operations from 1984 to 1985, and Deputy Chief of the Astronaut Office from 1987 to 1990. He left the Astronaut Office in June 1990 to become the Associate Director of NASA's Ames Research Center in California but returned to the Johnson Space Center in August 1992 as Deputy Director of Flight Crew Operations, and returned to astronaut flight status in February 1996. He was Director, Flight Crew Operations from October 2001 to November 2002, First Chief Astronaut for the NASA Engineering and Safety Center from 2003 to 2004, and Director of the Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science (ARES) Directorate from 2002 to 2008. He retired from NASA in May 2008. |

[88] | |

|

Jeffrey A. Hoffman | Brooklyn, New York November 2, 1944 |

Hoffman graduated from Scarsdale High School in Scarsdale, New York, in 1962, and earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in astronomy from Amherst College in 1966, a PhD in astrophysics from Harvard University in 1971, and a master's degree in materials science from Rice University in 1988. He flew in space five times:

Hoffman retired from the Astronaut Corps in 1997 to become NASA's European representative in Paris in 2008. He left NASA in August 2001 to become a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. |

[89][90][91] | |

|

Shannon M. W. Lucid | Shanghai, China January 14, 1943 |

Lucid graduated from Bethany High School in Bethany, Oklahoma, in 1960, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in chemistry from the University of Oklahoma in 1963, a Master of Science degree from the University of Oklahoma in 1970, and a PhD in biochemistry from the University of Oklahoma in 1973. She flew in space six times:

Lucid was NASA's Chief Scientist from February 2002 until September 2003, when she returned to the Astronaut Office. She retired from NASA in January 2012. |

[92][93] | |

|

Ronald E. McNair | Lake City, South Carolina, U.S. October 21, 1950 |

January 28, 1986 | McNair graduated from Carver High School in Lake City, South Carolina, in 1967, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in physics from North Carolina A&T State University in 1971, and a PhD in physics from Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1976. He flew space once:

On his second mission, he died in the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster:

|

[94] |

|

R. Michael Mullane | Wichita Falls, Texas, U.S. September 10, 1945 |

Mullane graduated from St. Pius X Catholic High School in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 1963, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in military engineering from the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, in 1967, and a Master of Science degree in aeronautical engineering from the Air Force Institute of Technology in 1975. He flew 150 combat missions in the Vietnam War as an McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II weapon system operator between January and November 1969. He completed the Flight Test Engineering Course with class 75B at the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in California, and was assigned as a flight test weapon system operator at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida. He flew in space three times:

He retired from NASA and the USAF on July 1, 1990. |

[95][96][97] | |

|

George D. Nelson | Charles City, Iowa, U.S. July 13, 1950 |

Nelson graduated from Willmar Senior High School in Willmar, Minnesota, in 1968, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in physics from Harvey Mudd College in 1972, a Master of Science from the University of Washington in 1974, and a PhD in Astronomy from the University of Washington in 1978. He flew in space three times:

He retired from NASA on June 30, 1989. |

[98][99] | |

|

Ellison S. Onizuka | Kealakekua, Hawaii, U.S. June 24, 1946 |

January 28, 1986 | Onizuka graduated from Konawaena High School in Kealakekua, Hawaii, in 1964, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in aerospace engineering from the University of Colorado in June 1969, and Master of Science degrees in aerospace engineering from the University of Colorado in December 1969. He flew in space once:

On his second mission, he died in the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster:

|

[100] |

|

Judith A. Resnik | Akron, Ohio, U.S. April 5, 1949 |

January 28, 1986 | Resnik graduated from Firestone High School in Akron, Ohio, in 1966, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in electrical engineering from Carnegie-Mellon University in 1970, and a doctorate in electrical engineering from the University of Maryland in 1977. She flew in space once:

On her second mission, she died in the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster:

|

[101] |

|

Sally K. Ride | Encino, Los Angeles, California, U.S. May 26, 1951 |

July 23, 2012 | Ride graduated from Westlake High School in Los Angeles, California, in 1968, and earned a Bachelor of Science in physics and a Bachelor of Arts in English from Stanford University in 1973, a Master of Science from Stanford University in 1975, and a PhD in physics from Stanford University in 1978. She flew in space twice:

Ride was a member of the Presidential Commission that investigated the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster. She left NASA on August 15, 1987. |

[102][103] |

|

Margaret Rhea Seddon | Murfreesboro, Tennessee November 8, 1947 |

Seddon graduated from Central High School in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, in 1965, and earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in physiology from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1970, and a Doctorate of Medicine degree from the University of Tennessee College of Medicine in 1973. She flew in space three times:

She retired from NASA on September 15, 1997. |

[104][105] | |

|

Robert L. Stewart | Washington, D.C., U.S. August 13, 1942 |

Stewart graduated from Hattiesburg High School in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, in 1960, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in mathematics from the University of Southern Mississippi in 1964, and a Master of Science degree in aerospace engineering from the University of Texas at Arlington in 1972. He joined the United States Army in May 1964, and flew 1,035 hours in combat in the Vietnam War with the 101st Aviation Battalion from August 1966 to 1967. He attended Rotary Wing Test Pilot Course at the U.S. Naval Test Pilot School at NAS Patuxent River in Maryland, graduating with class 65 in 1974, and was then assigned as an experimental test pilot to the U.S. Army Aviation Engineering Flight Activity at Edwards Air Force Base in California. He flew in space twice:

He was in training for a third flight known as STS-61-K, when he was selected for promotion to brigadier general. Upon accepting this promotion he returned to the Army as the Deputy Commanding General, US Army Strategic Defense Command, in Huntsville, Alabama. In 1989, he became the Director of Plans at the US Space Command in Colorado Springs, Colorado. He retired from the Army in 1992. |

[106] | |

|

Kathryn D. Sullivan | Paterson, New Jersey October 3, 1951 |

Sullivan graduated from Taft High School in Woodland Hills, California, in 1969, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in Earth sciences from the University of California, Santa Cruz, in 1973, and a PhD in geology from Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, in 1978. She flew in space three times:

She left NASA in March 1993 to become Chief Scientist of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). She served as Under Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere and NOAA Administrator on March 6, 2014, having been acting NOAA Administrator since February 28, 2013, and served until January 20, 2017. |

[107][108] | |

|

Norman E. Thagard | Marianna, Florida, U.S. July 3, 1943 |

Thagard graduated from Paxon Senior High School in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1961, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in engineering science from Florida State University in 1965, a Master of Science degrees in engineering science from Florida State University in 1966, and a Doctor of Medicine degree from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School in 1977. He flew in space six times:

He retired from NASA in December 1995. |

[109] | |

|

James D. A. van Hoften | Fresno, California, U.S. June 11, 1944 |

Van Hoften graduated from Mills High School in Millbrae, California, in 1962, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in civil engineering from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1966, a Master of Science degree in hydraulic engineering from Colorado State University in 1968, and a PhD in hydraulic engineering from Colorado State University in 1976.

He joined the Navy in 1969, and flew 60 combat missions in the Vietnam War as a McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II pilot with Fighter Squadron 154 (VF-154) aboard the aircraft carrier USS Ranger. From 1977 until 1980 he flew F-4 Phantoms with the United States Naval Reserve Fighter Squadron 201 (VF-201) at NAS Dallas, and then served for three years with the 147th Fighter Interceptor Group of the Texas Air National Guard. He flew in space twice:

He retired from NASA on June 17, 1986. |

[110][111] |

Nickname

Of the 73 astronauts in the seven groups before Group 8, only 27 were still active in 1978, and were outnumbered by the new class.[23] Group 8's name for itself was "TFNG". The abbreviation was deliberately ambiguous; for public purposes, it stood for "Thirty-Five New Guys"; however, within the group itself, it was known to stand for the military phrase, "the fucking new guy", used to denote newcomers to a unit.[112] The selection of a nickname started a tradition that has continued ever since.[113]

An official class patch was designed by NASA artist Robert McCall. It depicted the Space Shuttle, the number 35, and the year 1978. The class patch became another NASA tradition. Judy Resnik and Jim Buchli also designed a class logo depicting a Space Shuttle with 35 astronauts clinging to it. Below was the group name "TFNG" and the group motto "We Deliver". The artwork adorned coffee mugs and T-shirts, which came in red and blue for the two teams into which the TFNG were split.[114]

Demographics

The 35 new astronaut candidates were introduced to the public in a press conference at the Olin E. Teague auditorium at JSC on February 1, 1978. Most of the attention was on the six women, and, to a lesser extent, the four minority men.[115] Mike Mullane later recalled that the 25 white males were "invisible".[116] The hiring of the six women as astronaut candidates doubled the number of women in technical roles in JSC,[117] but they found counsellors and role models in Carolyn Huntoon and Ivy Hooks.[115] Huntoon was the most senior woman in a technical position at JSC, and became the default liaison between the six women astronaut candidates and NASA management.[117] She spoke with them before the initial news conference, and urged them to consider how much personal information they would divulge. They decided to adopt a group approach, and keep their private lives remaining private. The Houston Post chose to write about how the husbands of Fisher and Lucid had chosen to leave their jobs and move to Houston with their astronaut candidate wives.[118] Psychological testing soon showed that the women astronauts had far more in common with their male counterparts than with the female population of the United States as a whole.[119]

Of the 35 astronaut candidates, 20 came from the armed services, and four others (Terry Hart, David Griggs, Norman Thagard and Ox van Hoften) had previously served in the military but were civilians at the time of their selection. Twenty had served in combat. Of the 15 pilot astronaut candidates, eight came from the US Navy, six from the USAF, and one (David Griggs) was a NASA test pilot. All were test pilots, eight having graduated from the US Naval Test Pilot School at NAS Patuxent River, Maryland, and seven from the USAF Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in California. Of the twenty mission specialist astronaut candidates, seven came from the armed services, of whom four were from the USAF, and one each from the US Navy, USMC and US Army; Bob Stewart became the first Army officer to become an astronaut. Ten had never served in the military, although one of them, Katherine Sullivan, later served in the US Navy Reserve as an oceanographer from 1988 to 2006.[120] Ten of the 35 had bachelor's degrees, thirteen had master's degrees and twelve had doctorates.[121]

Training

Training was different from that of earlier astronaut classes in several ways, mainly because it was focused on the Space Shuttle. The human centrifuge was removed, since the Space Shuttle was not expected to subject the crew to more than 3 g (29 m/s2) on takeoff and 1.5 g (15 m/s2) on landing. Jungle and desert survival training were dropped as the Space Shuttle was not expected to land in such locations, although water survival training was continued.[122]

Nineteen of the 35 had already undergone this training in the military, so the remaining 16 (which included all six women) were sent to Homestead Air Force Base in Florida for training with the 3613th Combat Crew Training Squadron. The training was highly realistic, and concluded with each candidate being towed aloft under a parasail before being released 400 feet (120 m) above the water and dropped in while wearing their full flight gear. The candidate would then have to inflate their rubber raft, fire off a flare, and be plucked from the water by a waiting helicopter. This was followed by training at Vance Air Force Base in Oklahoma in the correct procedure in case they had to bail out of a T-38. This time 24 of the TFNGs had already completed this training, leaving just eleven, again including all six women.[123] In addition to the T-38, Kathy Sullivan and Pinky Nelson qualified as scientific operators on the Martin/General Dynamics WB-57F Canberra aircraft.[124]

Much of the first eight months of the astronaut candidates' training was in the classroom.[125] Because there were so many of them, the astronaut candidates did not fit easily into the existing classrooms, so during classroom instruction they were split into two groups, red and blue, led by Rick Hauck and John Fabian respectively, who were chosen because they were older and of higher military rank than the other candidates; as leaders they became the ones who would report to George Abbey.[126] Classroom training was given on a wide variety of subjects, including an introduction to the Space Shuttle program, space flight engineering, astronomy, orbital mechanics, ascent and entry aerodynamics and space flight physiology. Those accustomed to military and academic environments were surprised that subjects were taught, but not tested.[125] Training in geology, a feature of the training of earlier classes, was continued, but the locations visited changed because the focus was now on observations of the Earth rather than the Moon.[122]

The astronaut candidates were sent on a geological field trip to Arizona. They also visited Houston's Burke Baker Planetarium, the key NASA centers, including the Ames Research Center, Marshall Space Flight Center, Goddard Space Flight Center and Lewis Research Center, and Rockwell International's facility in Palmdale, California, where the Space Shuttle Orbiters were being built.[127] Zero gravity training was carried out in the "Vomit Comet", a modified Boeing KC-135 Stratotanker, and Extra-vehicular activity (EVA) training was conducted in the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory, an enormous water tank. Some accommodation had to be made for the women: Space suits were made in smaller sizes, the Shuttle's cargo bay doors were made easier to open, and the design of the Space Shuttle orbiters was modified to make it easier for women to negotiate and reach the switches.[128]

NASA maintained a small fleet of Northrop T-38 Talon jet aircraft at Ellington Field, not far from the JSC. These were used by the astronauts for visiting NASA and contractor installations around the country. They were also used as chase planes for the Space Shuttle, and it became a tradition for the crew to fly to KSC in T-38s before a mission. The T-38 was a trainer commonly used by the USAF and Navy, so most of the pilot astronaut candidates had flown it before, but none of the mission specialist candidates had, even among those who were trained pilots. Unlike previous astronaut groups, they were not sent to a military flight school to learn how to pilot the aircraft, but were required to learn how to fly in the back seat as a crew member. Jim Buchli and Dale Gardner had qualified for this role in the T-38 as Naval Flight Officers, and they drew up a training syllabus for mission specialist candidates with no flight experience that covered subjects such as navigation and the correct protocol for talking on the radio. Due the energy crisis of the 1970s and the consequent soaring cost of jet fuel, flight time was restricted to 15 hours a month.[129]

On August 31, 1979, NASA announced that the 35 astronaut candidates had completed their training and evaluation, and were now officially astronauts, qualified for selection on space flight crews. This brought the number of active astronauts to 62.[130] Their training, which had been expected to last 18 to 24 months, had been completed in just 14. Training of subsequent classes was shortened to just 12 months.[131] The initiation of a selection of the next class of astronaut candidates had already been announced on April 1.[132] Although NASA considered them astronauts, most did not feel like real astronauts until they were "veterans:" astronauts who had flown in space.[133] Had the Space Shuttle program been running on schedule, they would have been immediately assigned to flights, but it was now running more than two years behind. Veteran astronaut Alan Bean, the TFNG's coordinator, counseled patience, reminding them that the Group 7 astronauts had been waiting over ten years for their first flights.[134]

Operations

First missions

The first six Space Shuttle missions were orbital flight tests (OFTs). Each was commanded by a veteran astronaut, starting with John Young, a Next Nine astronaut who had walked on the Moon on Apollo 16, and piloted by a Group 7 astronaut on his first flight, starting with Bob Crippen. The TFNG performed support roles.[135] As with earlier classes, each astronaut was allocated an area of expertise to specialize in.[133] For the OFTs, the role of capsule communicator (CAPCOM), the astronaut at the Mission Control Center at JSC who spoke directly to the crew, was allocated to veteran astronauts, with a member of the TFNG as his backup, but Dan Brandenstein stepped up to become the CAPCOM for the ascent phase of the first mission, STS-1, when Ed Gibson retired.[135]

Once the OFTs were completed, the Space Shuttle could commence its designated role of launching satellites. The pilots of the STS-1 and STS-2, Bob Crippen and Dick Truly, were given command of STS-7 and STS-8 respectively, with TFNGs Rick Hauck and Dan Brandenstein assigned as their pilots.[136] This established a pattern that would continue of a pilot astronaut flying as a pilot on one mission, and then as a commander on the next. NASA management wanted a woman and an African American flown as soon as possible, so George Abbey selected Sally Ride and Guion Bluford. Chris Kraft thought that this decision should be considered further, so Bob Crippen, Carolyn Huntoon, Leonard S. Nicholson (the acting associate director of JSC) and Samuel L. Pool from NASA's Space Sciences directorate were consulted. Ultimately, John Fabian was named as MS-1 for STS-7, with Sally Ride as MS-2, and Guion Bluford as MS-1 for STS-8 with Dale Gardner as MS-2.[137]

The MS-1 on a Space shuttle flight sat behind the pilot on the flight deck, and monitored displays and checklists. The MS-2 was the flight engineer, and sat behind the commander. The Flight Engineer assisted the commander and pilot, and acted as the third member of the flight deck crew, and an additional set of eyes during the critical phases of a mission.[136] The hopes of NASA management that a CDR-PLT-MS2 team would be able to fly three or four missions a year were never realized.[138] After a single mission as pilot, a pilot astronaut became eligible to be commander on their next mission. Although some of the mission specialists were fully qualified pilots, none ever flew as pilot on a mission, and therefore never served as a mission commander. As more than one mission specialist flew on each flight, they began flying at a faster rate than their pilot classmates. Two pilot astronauts, David Griggs and Steven Nagel, flew their first missions as mission specialists. Nagel later flew as the pilot on STS-61-A and as the commander on STS-37 and STS-55.[139] Griggs was assigned as the STS-33 pilot, but he was killed in an air crash prior to the mission.[57]

Achievements

These missions began a sizable number of American spaceflight "firsts" achieved by the group:

- First American woman in space: Sally Ride (June 18, 1983, STS-7)[102]

- First African-American in space: Guion Bluford (August 30, 1983, STS-8)[75]

- First American woman to perform an EVA: Kathryn Sullivan (October 11, 1984, STS-41-G)[107]

- First mother in space: Anna Fisher (November 8, 1984, STS-51-A)[81]

- First Asian-American in space: Ellison Onizuka (January 24, 1985, STS-51-C)[100]

- First African-American to pilot and command a mission: Frederick Gregory (April 29, 1985, STS-51-B; November 23, 1989, STS-33)

- First American to launch on a Russian rocket: Norman Thagard (March 14, 1995, Soyuz TM-21)[109]

- First American woman to make a long-duration spaceflight: Shannon Lucid (March to September 1996, Mir NASA-1)[92]

- First American active duty astronauts to marry: Robert Gibson and Rhea Seddon[53][104]

- First Army astronaut: Bob Stewart[106]

Four members of the group, Dick Scobee, Judy Resnik, Ellison Onizuka and Ronald McNair, died in the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster[140] These four, plus Shannon Lucid, received the Congressional Space Medal of Honor, giving this astronaut class five total recipients of this top NASA award. This is second only to the New Nine class which received seven.[141] By the time of the Challenger disaster, all 35 members of the group had flown in space, and some had flown twice.[138]

Final missions

The last flight made by a member of the group was STS-93 in July 1999, which carried Steve Hawley into space for the fifth time. He had served as flight engineer on all five of his missions. The mission involved the deployment of the Chandra X-ray Observatory; nine years earlier he had help deploy the Hubble Space Telescope.[142] In all, the Group 8 astronauts flew 103 missions, totaling over 981 days in space. The leader was Shannon Lucid, who spent over 223 days in space over the course of five missions.[143]

Group 8 astronauts also performed important ground-based duties. Sally Ride served on both the Rogers Commission after the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986, and on the Columbia Accident Investigation Board after the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster in 2003.[102] Sixteen members of the group served various selection boards for later groups of astronauts, the first being for NASA Astronaut Group 10 in 1984.[144] Dan Brandenstein was Chief of the Astronaut Office from April 1987 through September 1992,[43] and Hoot Gibson from December 1992 to September 1994.[53] Dan Brandenstein had been CAPCOM for the first Space Shuttle mission in April 1981,[142] and Shannon Lucid continued to perform as CAPCOM duties for shuttle missions until and including STS-135, the final Space Shuttle mission in 2011. She retired on January 31, 2012.[145]

With Lucid's retirement, only Anna Fisher remained at NASA. She worked for the Capsule Communicator and Exploration branches of NASA as a station CAPCOM and on display development for the Orion project.[81] She was on the selection board for NASA Astronaut Group 20 in 2009,[144] the first group since 1978 who would not be trained to fly the Space Shuttle.[146] The role of mission specialist was abolished, and crew members who flew to the ISS were classified as flight engineers.[147] Fisher served as an ISS Capsule Communicator (CAPCOM) at the Mission Control Center from January 2011 through August 2013, and was the lead CAPCOM for Expedition 33 in 2012. She retired on April 29, 2017, the last of the Group 8 astronauts who had been selected nearly forty years before.[148] The Thirty Five New Guys reshaped the image of the American astronaut into one that reflected the diversity of American society, and they paved the way for future classes of astronauts, which would include women as pilots and commanders.[149]

Notes

- ^ a b Foster 2011, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Rivers 1973, pp. 460–461.

- ^ McQuaid 2007, p. 426.

- ^ a b McQuaid 2007, p. 425.

- ^ McQuaid 2007, p. 424.

- ^ a b McQuaid 2007, p. 428.

- ^ a b c d McQuaid 2007, p. 431.

- ^ a b McQuaid 2007, p. 430.

- ^ a b Holden, Constance (November 23, 1973), "NASA: Sacking of Top Black Woman Stirs Concern for Equal Employment", Science, 182 (4114): 804–807, Bibcode:1973Sci...182..804H, doi:10.1126/science.182.4114.804, PMID 17772151, S2CID 22222809, retrieved September 16, 2020

- ^ Ruel, Mills & Thomas 2018, p. 32.

- ^ McQuaid 2007, p. 434.

- ^ Delaney, Paul (October 28, 1973). "Top Black Woman is Ousted by NASA". The New York Times. p. 23. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ McQuaid 2007, pp. 436–438.

- ^ "Ruth Bates Assumes New Post at NASA" (PDF). The Astrogram. Vol. 16, no. 25. September 12, 1974. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ McQuaid 2007, p. 442.

- ^ "Harriett G. Jenkins's Biography". The History Makers. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, p. 135.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, pp. 138–139.

- ^ a b Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Santy 1994, p. 51.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, p. 175.

- ^ a b c d e f Reim, Milton (January 16, 1978). "NASA Selects 35 Astronaut Candidates" (PDF) (Press release). NASA. 78-03. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 8, 2023. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, p. 1.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, p. 147.

- ^ a b "NASA to Recruit Space Shuttle Astronauts" (PDF) (Press release). NASA. July 8, 1976. 76-44. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 15, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, p. 7.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, pp. 154–155.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, pp. 162–163.

- ^ "Over 8,000 Apply for Space Shuttle Astronaut Program at JSC" (PDF) (Press release). NASA. July 15, 1977. 77-39. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 2, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, pp. 163–165.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, p. 14.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Scrivo, Karen L. (August 3, 1986). "She Still Has the Right Stuff: Test Pilot Succeeds Despite Restrictions". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c Shayler & Burgess 2020, p. 84.

- ^ a b Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 12–15.

- ^ Santy 1994, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 31–32.

- ^ a b Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 535–547.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, p. 123.

- ^ a b "Astronaut Bio: Daniel C. Brandenstein" (PDF). NASA. October 2007. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Campion, Ed; Schwartz, Barbara (July 1, 1991). "Chief Astronaut to Retire from Navy and Leave Nasa" (Press release). NASA. 92-100. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 81–82.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Michael L. Coats" (PDF). NASA. May 2008. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Campion, Ed; Schwartz, Barbara (July 2, 1991). "Astronaut Coats to Leave NASA" (Press release). NASA. 91-104. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 82–84.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Richard O. Covey" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ Campion, Ed; Herring, Kyle (July 2, 1991). "Shuttle Astronaut Richard Covey to leave NASA, Air Force" (Press release). NASA. 94-110. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: John O. Creighton" (PDF). NASA. December 1994. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ Campion, Edward; Schwartz, Barbara (June 25, 1992). "Astronaut Creighton to Retire And Leave NASA" (Press release). NASA. 92-96. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Astronaut Bio: R. L. Gibson" (PDF). NASA. November 1996. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Campion, Ed; Hawley, Eileen (November 6, 1996). "Veteran Shuttle Commander Retires" (Press release). NASA. 96-229. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Frederick D. Gregory" (PDF). NASA. October 2005. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 86–88.

- ^ a b "Astronaut Bio: David Griggs" (PDF). NASA. June 1989. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Frederick (Rick) Hauck" (PDF). NASA. November 2007. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 89–90.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: J. McBride" (PDF). NASA. June 2008. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 90–91.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Steve Nagel" (PDF). NASA. January 2006. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Dick Scobee" (PDF). NASA. December 2003. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 92–93.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Brewster H. Shaw" (PDF). NASA. February 2006. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 94–95.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Loren J. Shriver" (PDF). NASA. May 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 4, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, p. 497.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: David Walker" (PDF). NASA. April 2001. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Campion, Ed; Hawley, Eileen (April 12, 1996). "Astronauts Walker, Harris Leave Astronaut Corps" (Press release). NASA. 96-70. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 95–96.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Donald E. Williams" (PDF). NASA. December 1993. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Campion, Ed; Space, Johnson (February 27, 1990). "Veteran Shuttle Astronaut Williams to Retire from Nasa, Navy" (Press release). NASA. 90-31. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ a b "Astronaut Bio: Guion S. Bluford, Jr" (PDF). NASA. May 2008. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Campion, Ed; Schwartz, Barbara (June 15, 1993). "Astronaut Bluford Leaves NASA" (Press release). NASA. 93-113. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 101–102.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: James F. Buchli" (PDF). NASA. December 1993. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: John M. Fabian" (PDF). NASA. December 1993. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ "The New Shuttle Crews are Named". Lodi News-Sentinel. Lodi, California. September 20, 1985.

- ^ a b c "Astronaut Bio: Anna Fisher" (PDF). NASA. October 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 478–479.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Dale A. Gardner" (PDF). NASA. December 1994. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 484–485.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Terry J. Hart" (PDF). NASA. January 2006. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Nesbitt, Steve (May 10, 1984). "Astronaut T. J. Hart to Leave NASA" (PDF) (Press release). NASA. 84-027. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 4, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 485–486.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Steve Hawley" (PDF). NASA. August 2008. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: J. Hoffman" (PDF). NASA. September 2002. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Rahn, Debbie (July 9, 1997). "Jeff Hoffman Retires From Astronaut Corps" (Press release). NASA. 97-151. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 486–487.

- ^ a b "Astronaut Bio: Shannon Lucid" (PDF). NASA. January 2008. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Buck, Joshua; Cloutier-Lemasters, Nicole (January 31, 2012). "Legendary Astronaut Shannon Lucid Retires From NASA" (Press release). NASA. 12-038. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Ronald McNair" (PDF). NASA. December 2003. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Richard M. Mullane" (PDF). NASA. January 1996. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Campion, Ed; Carr, Jeff (July 1, 1990). "End of Transmission" (Press release). NASA. 90-28. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 112–113.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: George D. "Pinky" Nelson" (PDF). NASA. April 1989. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Carr, Jeffrey (June 9, 1989). "Astronaut "Pinky" Nelson to Leave NASA" (PDF) (Press release). NASA. 89-034. Retrieved October 2, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Astronaut Bio: Ellison Onizuka" (PDF). NASA. January 2007. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Judith A. Resnik (Ph.D.)" (PDF). NASA. December 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 23, 2019. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Astronaut Bio: Sally K. Ride" (PDF). NASA. July 2006. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Specter, Michael (May 27, 1987). "Astronaut Sally Ride to Leave NASA". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ a b "Astronaut Bio: M. R. Seddon" (PDF). NASA. November 1998. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Campion, Ed (September 10, 1996). "Seddon to Support Life Science Investigations at Vanderbilt" (Press release). NASA. 96-185. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ a b "Astronaut Bio: Robert L. Stewart" (PDF). NASA. December 1993. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ a b "Astronaut Bio: Kathryn D. Sullivan" (PDF). NASA. October 2005. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 498–499.

- ^ a b "Astronaut Bio: N. E. Thagard" (PDF). NASA. August 1995. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: James D. A. (Ox) van Hoften" (PDF). NASA. December 1993. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Gawdiak, Miró & Stueland 1997, p. 46.

- ^ Mullane 2007, p. 63.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, p. 134.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 135–137.

- ^ a b Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Mullane 2007, p. 31.

- ^ a b Shayler & Burgess 2020, p. 151.

- ^ Ross-Nazzal 2008, p. 66.

- ^ Santy 1994, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, p. 138.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, p. 139.

- ^ a b Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 171–175.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 182–183.

- ^ a b Shayler & Burgess 2020, p. 177.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, p. 167.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, p. 184.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 187–189.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 166–168.

- ^ Reim, Milton (August 31, 1979). "35 Astronaut Candidates Complete Training and Evaluation Period" (PDF) (Press release). NASA. 79-53. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 13, 2022. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Reim, Milton (August 31, 1979). "NASA to Recruit Space Shuttle Astronauts" (PDF) (Press release). NASA. 79-50. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 13, 2022. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ a b Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 196–198.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, p. 190.

- ^ a b Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 283–285.

- ^ a b Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 290–293.

- ^ a b Shayler & Burgess 2020, p. 334.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, p. 65.

- ^ "The Crew of the Challenger Shuttle Mission in 1986". NASA. October 22, 2004. Retrieved October 18, 2008.

- ^ "Congressional Space Medal of Honor". NASA. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- ^ a b Shayler & Burgess 2020, p. 457.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, p. 551.

- ^ a b Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 479–481.

- ^ "Shuttle-era astronauts Lucid and Ross retire from NASA". Spaceflight Now. January 31, 2012. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2020, p. 529.

- ^ Sumner, Megan (April 29, 2017). "Legendary Astronaut Retires from NASA" (Press release). NASA. J17-005. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Ross-Nazzal 2008, p. 70.

References

- Atkinson, Joseph D.; Shafritz, Jay M. (1985). The Real Stuff: A History of NASA's Astronaut Recruitment Program. Praeger special studies. New York, New York: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-03-005187-6. OCLC 12052375.

- Foster, Amy E. (2011). Integrating Women into the Astronaut Corps: Politics and Logistics at NASA, 1972–2004. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0195-9. OCLC 775730984.

- Gawdiak, Ihor Y.; Miró, Ramón J.; Stueland, Sam (1997). Astronautics and Aeronautics, 1986-1990: A Chronology. The NASA History series. Washington, DC: NASA History Office. ISBN 978-0-16-049134-4. OCLC 36824938. SP-4027.

- McQuaid, Kim (2007). ""Racism, Sexism, and Space Ventures": Civil Rights at Nasa in the Nixon Era and Beyond". In Dick, Steven J.; Launius, Roger D. (eds.). Societal Impact of Spaceflight (PDF). Washington, DC: NASA Office of External Relations, History Division. pp. 422–449. SP-4801. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- Mullane, Mike (2007). Riding Rockets: The Outrageous Tales of a Space Shuttle Astronaut. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-7683-2. OCLC 671034758.

- Rivers, Richard R. (1973). "In America, What You Do Is What You Are: The Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972". Catholic University Law Review. 22 (2): 455–466. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- Ross-Nazzal, Jennifer (Fall 2008). "Legacy of the 35 New Guys" (PDF). Houston History. 6 (1). ISSN 2165-6614. Retrieved October 5, 2020.