Round (music)

A round (also called a perpetual canon [canon perpetuus], round about or infinite canon) is a musical composition, a limited type of canon, in which multiple voices sing exactly the same melody, but with each voice beginning at different times so that different parts of the melody coincide in the different voices, but nevertheless fit harmoniously together.[2] It is one of the easiest forms of part singing, as only one line of melody need be learned by all singers, and is part of a popular musical tradition. They were particularly favoured in glee clubs, which combined amateur singing with regular drinking.[3] The earliest known rounds date from 12th-century Europe. One characteristic of rounds is that, "there is no fixed ending", in the sense that they may be repeated as many times as possible, although many do have "fixed" endings, often indicated by a fermata.[1]

"Row, Row, Row Your Boat" is a well-known children's round for four voices. Other well-known examples are "Frère Jacques", "Three Blind Mice", "Kookaburra", and, more recently, the outro of "God Only Knows" by The Beach Boys.[4]

A catch is a round in which a phrase that is not apparent in a single line of lyrics emerges when the lyrics are split between the different voices. Rounds that fall into the category of "perpetual canon" feature a melody whose end leads back to the beginning, allowing easy and immediate repetition. Often, "the final cadence is the same as the first measure".[5]

History

The term "round" first appears in English in the early 16th century, though the form was found much earlier. In medieval England, they were called rota or rondellus. Later, an alternative term was "roundel" (e.g., David Melvill's manuscript Ane Buik off Roundells, Aberdeen, 1612). Special types of rounds are the "catch" (a comic English form found from about 1580 to 1800), and a specialized use of the word "canon", in 17th- and 18th-century England designating rounds with religious texts.[2] The oldest surviving round in English is "Sumer is icumen in"[4] ⓘ, which is for four voices, plus two bass voices singing a ground (that is, a never-changing repeating part), also in canon. However, the earliest known rounds are two works with Latin texts found in the eleventh fascicle of the Notre Dame manuscript Pluteo 29.1. They are "Leto leta concio"[7] (a two-voice round) and "O quanto consilio" (a four-voice round). The former dates from before 1180 and may be of German origin.[8] The first published rounds in English were printed by Thomas Ravenscroft in 1609... "Three Blind Mice" appears in this collection, although in a somewhat different form from today's children's round:ⓘ

|

|

Mechanics

The canon, or rule, of a simple round is that each voice enters after a set interval of time, at the same pitch, using the same notes.[10]

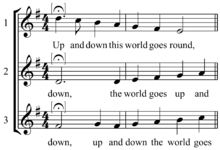

Rounds work because after the melody is divided into equal-sized blocks of a few measures each, corresponding notes in each block either are the same, or are different notes in the same chord. This is easiest with one chord, as in "Row, Row, Row Your Boat".ⓘ

A new part can join the singing by starting at the beginning whenever another part reaches any asterisk in the above music. If one ignores the eighth notes that pass between the main chords, every single note is in the tonic triad—in this case, a C, E, or G.

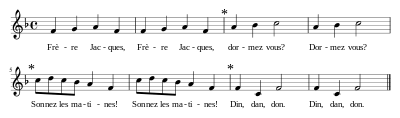

Many rounds involve more than one chord, as in "Frère Jacques" ⓘ:

The texture is simpler, but it uses a few more notes; this can perhaps be more easily seen if all four parts are run together into the same two measures:

The second beat of each measure does not sketch out a tonic triad, it outlines a dominant seventh chord (or "V7 chord").

Classical

Classical composers who turned their hand to the round format include Thomas Arne, John Blow, William Byrd, Henry Purcell, Moondog (Louis Hardin), Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven, and Benjamin Britten (for example, "Old Joe Has Gone Fishing", sung by the villagers in the pub to keep the peace, at the end of act 1 of Peter Grimes) .[12] Examples by J. S. Bach include the regular canons, variations 3 and 24 of the Goldberg Variations, and the perpetual canons, canon 7 of The Musical Offering and "Canon a 2 Perpetuus" (BWV 1075).[13] Several rounds are included amongst Arnold Schoenberg's thirty-plus canons, which "within their natural limitations ... are brilliant pieces, containing too much of the composer's characteristically unexpected blend of seriousness, humour, vigour and tenderness to remain unperformed".[14] Contemporary classical composers, such as Abbie Betinis, have also explored round-writing in the 21st century.[15]

Rounds in German

See also

References

- ^ a b MacDonald & Jaeger 2006, p. 15.

- ^ a b Johnson 2001.

- ^ Aldrich 1989, Introductory essay, 8–22, especially at p. 21: "Catch-singing is unthinkable without a supply of liquor to hand...".

- ^ a b Hoffman 1997, p. 40.

- ^ Walton 1974, p. 141.

- ^ & Norden 1970, p. 195.

- ^ Leto Leta Concio: Canon – Manuscrit de Florence on YouTube

- ^ Falck 1972, pp. 43–45, 57.

- ^ "Three Blind Mice", Ravenscroft Songbook

- ^ Mead 2007, p. 371.

- ^ MacDonald & Jaeger 2006, p. 8.

- ^ Howard 1969, p. 15.

- ^ Smith 1996.

- ^ Neighbour 1964, p. 681.

- ^ "Abbie Betinis, Choral Works (selected)". abbiebetinis.com. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

Sources

- Aldrich, Henry (1989). Robinson, B. W.; Hall, R. F. (eds.). The Aldrich Book of Catches. London: Novello.

- Falck, Robert (1972). "Rondellus, Canon, and Related Types before 1300". Journal of the American Musicological Society. 25 (1 (Spring)): 38–57. doi:10.2307/830299. JSTOR 830299.

- Hoffman, Miles (1997). The NPR Classical Music Companion: Terms and Concepts from A to Z. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-61-861945-0..

- Howard, Patricia (1969). The Operas of Benjamin Britten; An Introduction. New York and Washington: Frederick A. Praeger.

- Johnson, David (2001). "Round". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.23960. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- MacDonald, Margaret Read; Jaeger, Winifred (2006). The Round Book: Rounds Kids Love to Sing. Little Rock: August House. ISBN 978-0-87-483786-5.

- Mead, Sarah (2007). "Renaissance Theory". In Kite-Powell, Jeffery (ed.). A Performer's Guide to Renaissance Music (2nd ed.). Bloomington: Early Music Institute Indiana University Press. pp. 343–373. ISBN 978-0-253-34866-1.

- Neighbour, Oliver W. (1964). "Schoenberg's Canon's". The Musical Times. 105 (1459 (September)): 680–81. doi:10.2307/950274. JSTOR 950274.

- Norden, Hugo (1970). The Technique of Canon. Branden Books. ISBN 978-0-82-831839-6.

- Smith, Timothy A. (1996). "Anatomy of a Canon". The Canons and Fugues of J. S. Bach. Northern Arizona University. Archived from the original on 2009-04-28.

- Walton, Charles W. (1974). Basic Forms in Music. New York: Alfred Publishing. ISBN 978-0-88-284010-9.

External links

Media related to Rounds (music) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rounds (music) at Wikimedia Commons