Mongol invasion of Persia and Mesopotamia

| Mongol conquest of Persia & Mesopotamia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mongol invasions and conquests | |||||||||

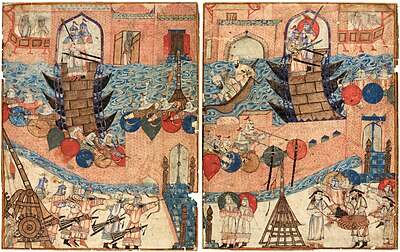

The Siege of Baghdad, in which the Mongols decisively secured their hegemony over Mesopotamia | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Mongol Empire | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 10–15 million people killed[1] | |||||||||

The Mongol conquest of Persia and Mesopotamia comprised three Mongol campaigns against islamic states in the Middle East and Central Asia between 1219 and 1258. These campaigns led to the termination of the Khwarazmian Empire, the Nizari Ismaili state, and the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad, and the establishment of the Mongol Ilkhanate government in their place in Persia.

Genghis Khan had unified the Mongolic peoples and conquered the Western Xia state in the late 12th and early 13th centuries. After a series of diplomatic provocations on the part of Muhammad II, the ruler of the neighbouring Khwarazmian Empire, the Mongols launched an invasion in 1219. The invaders laid waste to the Transoxianan cities of Bukhara, Samarkand, and Gurganj in turn, before obliterating the region of Khorasan, slaughtering the inhabitants of Herat, Nishapur, and Merv, three of the largest cities in the world. Muhammad died destitute on an island in the Caspian Sea. His son and successor, Jalal al-Din, tried to resist the Mongols, but was defeated and forced into exile. Genghis returned to his campaign against the Jin dynasty in 1223, only retaining governance of the northern Khwarazmian regions.

The war had been one of the bloodiest in human history, with total casualties estimated to be between two and fifteen million people. The next three decades saw conflicts of lesser scale but equal destruction in the region. Soon after his accession to the khaganate in 1227, Ögedei Khan sent an army under Chormaqan Noyan to end Jalal al-Din's renewed resistance and subjugate several minor polities in Persia. This was carried out gradually: al-Din was killed in 1231, with Isfahan and Maragheh being besieged and captured the same year; Erbil was captured in 1234; and Georgia was gradually subjugated and vassalised before Chormaqan's death in 1241. Several other Persian towns and cities, such as Hamadan, Ray, and Ardabil, were also captured by the Mongols.

The final stage began in 1254. On the orders of his brother, Möngke Khan, Hulagu systematically captured the fortresses of the Nizari Ismaili state in northern Persia, seizing their capital of Alamut in 1256. In 1258, Hulagu marched on the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad; capturing the city, he ended the 500-year-old Abbasid dynasty by killing the caliph Al-Musta'sim, marking the end of the Islamic Golden Age. Persia would later become the heartland of the Mongol Ilkhanate.

Background

Iran's military and political conditions before the invasion

Expansion of Shah Muhammad's territory and war with Abbasid Caliph Al-Nasir

After the fall of the Seljuks of Persian Iraq, with the defeat of Toghrul III by Ala al-Din Tekish (the father of Shah Muhammad), a severe enmity arose over the governance of Western Iran between the Abbasid caliph Al-Nasir and Ala al-Din Tekish. These conflicts continued during the reign of Shah Muhammad, and Western Iran became the battleground of the Khwarazmian troops and the caliphate troops. In order to destroy the Khwarazmian Empire, Al-Nasir not only provoked the Ghurids and fanatical religious scholars from Transoxiana against it, but also asked help from the Nizari Ismaili state, the Qara Khitai and Mongol tribes. These actions eventually not only led to the overthrow of the Khwarazmian Empire, but also the subsequent overthrow of the Abbasid government.[2]: 338

Simultaneously with the coronation of Shah Muhammad, the Ghurids captured the remaining lands of the Ghaznavids and Khorasan cities such as Balkh. Shah Muhammad defeated the Ghurid dynasty in 1212 and captured Ghazni in 1215, thus he extended the border of his territory to India from the east. In 1209, he conquered Mazandaran, which had been held by the Bavands for a long time. In the 12th century, a group of Khitan people from North China who were Buddhists, had formed a large political entity in the province of Kashgar and Hotan called Qara Khitai. In order to block their expansionism, the Khwarazmians had agreed to pay them a yearly tribute. This custom continued until the times of Shah Muhammad, but then he refused to pay tribute to the "polytheist" king. Shah Muhammad fought three times with the Qara Khitai. At last in 1210, the Shah asked for help from Kuchlug, a prince and leader of the Naimans, in order to defeat the Qara Khitai. Kuchlug defeated them in Transoxiana and conquered Bukhara and Samarkand, usurping the Qara Khitai Empire from his father-in-law Yelü Zhilugu.[3]: 22–25 [4]

After conquering Transoxiana, Kuchlug alienated both his subjects and the Khwarazmian Empire with anti-Muslim measures. As a Mongol detachment led by Jebe hunted Kuchlug down, he fled; meanwhile, Muhammad was able to vassalize the territories of Balochistan and Makran in modern-day Pakistan and Iran, and to gain the allegiance of the Eldiguzids.[5]

After extending the borders of the Khwarazmian Empire from the north-east and east to Kashgar and the Sindh, Shah Muhammad decided to conquer the west, i.e. Iraq. At that time, these lands were in the hands of the Eldiguzids and Salghurids, and the authority of the Abbasid caliph's clergymen remained partly in these two regions. Shah Muhammad was at enmity with the Abbasid caliph, because the caliph asked for help from the Ismailis and the Qara Khitai to overthrow his rule and also because the shah wanted the authority of the Khwarazmians sentence in Baghdad. As a result of this dispute and enmity, Shah Muhammad received a fatwa from the scholars of his country that "Bani Abbas" do not deserve the caliphate and one of "Husayni Sadat" (a person from the generation of Imam Husayn) should be chosen for this position. Therefore, he declared the caliph deposed and ordered that the name of the Abbasid caliph should not be mentioned in sermons and not be inserted on coins, and appointed one of the Termezi Alawi Sadats, as the caliphate. In 1217, Shah Muhammad marched towards Baghdad, but because it was winter, his troops suffered a lot from the snow and cold in the Asadabad pass between Kermanshah and Hamadan, and thus he returned to Khorasan.[3]: 22–25 [5]

The reasons for the invasion

The incident of killing the Mongol merchants in Otrar

Genghis Khan conquered Beijing after raiding northern China. Then he forced the Uyghur clans to obey him, Kuchlug Khan, the leader of the Naiman tribes, who had dominated the lands of the Qara Khitai tribes, was driven from there, and thus Genghis found a common border with the Khwarazmian Empire, whose eastern border had reached these areas. Genghis was very interested in the spread of commerce and the movement of merchants, therefore he encouraged commerce and tried to establish friendly relations with Shah Muhammad II, whom he considered as a powerful king. So, he sent a group of his merchants headed by Mahmud Yalavach with gifts to visit Shah Muhammad and inform him about the size of his country, prosperity of his possessions, and the strength of his army. Shah Muhammad, who was trying to expand Khwarazmia's territory, got angry that Genghis had called him "his son" in his letter, but Mahmud Yalavach quelled his anger and made him agree to establish friendly relations with Genghis Khan.[6]

In this way, the first ambassador of Shah Muhammad was accepted in Beijing, and Genghis declared trade between the Mongols and Khwarazmians as a necessity for establishing friendly relations. During this situation, a number of Muslim merchants from Shah Muhammad's territory took some goods to the Mongol Empire, and although Genghis treated them violently at the beginning of their arrival, he finally appeased them and sent them back with respect. At the time that they were returning in 1218, a number of Mongol merchants, whose number reached 450 and apparently most of them were Muslims, was sent by Genghis with some goods and a letter containing his advice and request to establish relations between the two governments. But Inalchuq, the ruler of Otrar who was the nephew of Terken Khatun (Shah Muhammad's mother) and supported by her, was greedy for the wealth of the merchants and arrested the Mongol merchants on the charge of espionage on the border of the territory under his rule, and then with the permission of Shah Muhammad, who was in Persian Iraq at that time, massacred all these merchants.[7]: 522 Then the officials of the Khwarazmian Empire sold the cargo of the caravan, which included 500 camels of gold, silver, Chinese silk artefacts, precious skins and such on, and sent the resulting amount to the capital of the Khwarazmian government.[8]: 701 [9]

When the news of Otrar incident reached Genghis Khan, he decided to control his anger and made his last attempt to gain satisfaction through diplomacy. He sent a Muslim, who was previously in the service of Ala al-Din Tekish and was accompanied by two Mongols, to protest against the performance of Inalchuq and requested to surrender him to the Mongols.[10]: 305 Shah Muhammad didn't want to surrender Inalchuq because most of the leaders of the Khwarazmian army were his relatives, and also Terken Khatun who had influence in the Khwarazmian court was supporting him. Therefore, Shah Muhammad not only did not accept Genghis Khan's request, but also executed his Muslim envoy who came to Samarkand, the capital of the Khwarazmian Empire, and sent his companions back to Genghis Khan with their beards and mustaches cut off. This bellicose behavior of Shah Muhammad accelerated the Mongol invasion of Central Asia.[8]: 701 [11] Historians cite the fact that Genghis was already bogged down in his war against the Jin in China, and that he had to deal with the Hoi-yin Irgen rebellion in Siberia in 1216, so he didn't want to start another war.[12]

Economic factors

The Mongols had a need for the goods of more advanced regions; therefore, it was very important for them to keep trade routes open since ancient times.[3]: 569 From the beginning of his monarchy, Genghis Khan attached great importance to commerce because he needed to procure weapons from India and Damascus; he also needed markets to sell Mongolian and Chinese products. But the conflict between Shah Muhammad and Kuchlug Khan, the leader of the Naimans, had caused the closure of the roads and the interruption between the east and west trade. At the same time as this interruption in the land routes, the sea route of the Persian Gulf was also blocked due to the war between the ruler of Kish and the ruler of Hormuz, which resulted in a trade crisis in the Central Asian region. The merchants wanted the end of the conflicts and the opening of the roads. Hence, during the Mongols' attacks, some Muslim merchants helped Genghis to progress to the west. To solve this crisis, Kuchlug Khan was killed by the Mongols in 1218. Shah Muhammad didn't care to the importance of trade relations with the Far East and the significance of the location of his lands on the Silk Road, and he was indifferent to the merchants' needs and Genghis' wishes, so after removing Kuchlug Khan, it was Shah Muhammad's turn.[13]

Genghis' army raid

ِDespite Muhammad II's apparent authority, he was unprepared to defend his polity in case of the Mongol attack. During preparations for the war, he collected taxes from his people three times in one year, causing dissatisfaction and unrest among the population.[8]: 707 Before the invasion, Shah Muhammad formed a council composed of his army commanders. Imam Shahab al-Din Khiyoqi, one of the famous jurists and teachers of Khwarazm, proposed to bring as many soldiers as possible from different corners of the empire and prevent Mongols from crossing Syr Darya (medieval Arabs called this river Seyhan) but the commanders of the Khwarazmian army did not fancy his plan. They suggested that they wait for the Mongols to arrive to Transoxiana and reach the difficult straits. They also proposed to attack the Mongols when they would be having certain difficulties considering their supposed lack of knowledge of the loсal terrain. The Shah didn't give importance to the counsel of Shahab al-Din, and accepted the plan of scattering his troops to protect major cities of the empire. In the meanwhile, Shah Muhammad left for Balkh.[3]: 39 [10]: 306

The conquest of Transoxiana

In September 1219, Genghis Khan arrived at Otrar, on the border of the Khwarazmian territory, and divided his forces into three parts; He assigned one part to his sons Ögedei and Chagatai to besiege Otrar, sent another part under the command of Jochi to take the cities around the Syr Darya towards the city of Jand, and he himself moved towards Bukhara with his son Tolui at the head of the main forces.[8]: 702 Genghis always used the services of advisers, roadmen and merchants during his campaigns. Therefore, there was always a group of Muslim merchants who were familiar with the roads of Khwarazmia, and were in his camp for their advice.[14] Also, after the start of the invasion, some of the commanders of Khwarazmia who were hostile to the Shah, like Badr al-Din Omid, whose father and uncle were killed by the order of Shah Muhammad, also joined the Mongol army and gave a lot of information to Genghis Khan about the situation in the Shah's court and the roads. From the method of attack, the division of the army and other decisions of Genghis Khan, it can be said that Genghis was really well familiar with the geographical situation of Transoxania.[3]: 41, 91

The conquest of Bukhara, Samarkand and Otrar

In 1220, Genghis Khan attacked Bukhara with the main forces of his army. Shah Muhammad was caught completely unaware. He had anticipated that Genghis would attack Samarkand first, where both his field army and the garrison stationed at Bukhara would relieve the siege. The Khan's march through the Kyzylkum Desert had left the Shah's field army impotent, unable to either engage the enemy or help his people.[15] The Khan faced strong resistance from the defenders of the city; But this resistance did not last long. The city fell in less than two weeks, because the city's communication routes were cut off from all sides, and so they Inevitably gave up their resistance. After capturing Bukhara, the Mongol invaders killed thousands of unarmed and defenseless citizens and took the rest as slaves.[4]: 34 [8]: 702 [16]: 133 Genghis Khan summoned the elders of Bukhara and told them that the purpose of summoning them is to collect the assets that Shah Muhammad had sold to merchants (The Otrar Incident), because these objects belonged to the Mongols. They brought all the property they had from the Otrar caravan and handed them over to Genghis Khan.[3]: 44 Then they took the road to Samarkand.

Shah Muhammad greatly emphasized the defense of Samarkand and had gathered a large force in this city and the fortifications of the city had been repaired. According to various historians, between 50,000 and 110,000 soldiers had gathered in Samarkand to defend the city. It seems that the city could have resisted the siege for several years. On the third day of the siege, a group of the city's defenders came out of their positions and attacked the enemy. They killed some of the Mongol soldiers, but then they were surrounded by the enemy, and most of them perished on the battlefield. This unsuccessful attack had an unfortunate effect on the morale of the defenders. Some influential people of the city decided to surrender and sent the qadi and Shaykh al-Islām of the city to Genghis Khan to talk about surrender. Finally, they opened the gates of the city to the enemy, and Genghis' army entered the city and massacred and looted the people. After the attack, the city of Samarkand became a ruin and was deserted.[8]: 703 [15]Mongol soldiers took the city of Otrar after a decisive attack, but the fortress of Otrar resisted for a month (according to some documents, six months). After taking the fortress of Otrar, Mongols killed all the defenders of the city and the fortress.[8]: 702 [10]: 307

References

- ^ Ward, Steven R. (2009). Immortal: A Military History of Iran and Its Armed Forces. Georgetown University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-58901-587-6. Archived from the original on 2024-05-12.

Overall, the Mongol violence and depredations killed up to three-fourths of the population of the Iranian Plateau, possibly ten to fifteen million people.

- ^ Abbas Eqbal Ashtiani (1931). "The strange life of one of the Abbasid caliphs (Al-Nasir al-Din Allah)" زندگانی عجیب یکی از خلفای عباسی (ناصرالدین الله). Sharq (6).

- ^ a b c d e f Abbas Eqbal Ashtiani (1985). The Mongol History تاریخ مغول. Negah Publishing House. ISBN 9789643514525.

- ^ a b Jackson, Peter (2009). "The Mongol Age in Eastern Inner Asia". The Cambridge History of Inner Asia. The Chinggisid Age: 26–45. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139056045.005. ISBN 9781139056045.

- ^ a b Rafis Abazov (2008). Palgrave Concise Historical Atlas of Central Asia. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 43. ISBN 978-1403975423.

- ^ Husayngoli Sotoudeh (1974). "The role of Persian people in defending against the Mongol invasion" (Collection of speeches of the first Iranian Research Congress) 2 »نقش مردم ایران در مدافعه از تهاجم مغولان». مجموعه خطابههای نخستین کنگره تحقیقات ایرانی. ۲. University of Tehran Press. p. 406.

- ^ Abdolhossein Zarrinkoob (1996). Other periods: periods of Iran: from the end of the Sassanids to the end of the Timurids روزگاران دیگر: دنباله روزگاران ایران: از پایان ساسانیان تا پایان تیموریان. Sokhan Publications. ISBN 9789646961111.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bobojon Ghafurov (1998). "Tajiks". Ancient, ancient, medieval and modern history Book 1,2. Dushanbe.

- ^ Leo de Hartog (2004). Genghis Khan: Conqueror of the World. Tauris Parke. pp. 86–87. ISBN 1-86064-972-6.

- ^ a b c John Andrew Boyle (1968). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 5: The Saljuq and Mongol Periods. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139054973.

- ^ Ata-Malik Juvaini (c. 1260). Tarikh-i Jahangushay تاریخ جهانگشای [History of the World Conqueror] (in Persian). Vol. 1. Translated by Andrew Boyle, John. p. 80.

- ^ May, Timothy (2018). "The Mongols outside Mongolia". The Mongol Empire. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 44–75. ISBN 9780748642373. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctv1kz4g68.11.

- ^ Peter Avery (1959). "Investigating the factors of Genghis Khan's attack on Transoxiana" بررسی عوامل حمله چنگیز خان به ماوراءالنهر. Quarterly Magazine Faculty of Literature and Human Sciences, University of Tehran (1): 42–45.

- ^ "Iran – The Mongol invasion". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ a b Sverdrup, Carl (2017). The Mongol Conquests: The Military Campaigns of Genghis Khan and Sübe'etei. Helion & Company. pp. 151–153. ISBN 978-1913336059.

- ^ David O. Morgan, Anthony Reid (2008). The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 3: The Eastern Islamic World, Eleventh to Eighteenth Centuries. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521850315.