Mitchel Air Force Base

| Mitchel Air Force Base | |

|---|---|

| Part of Air Defense Command | |

| Located near: Uniondale, New York | |

Looking west in 1968, the airfield is mainly intact. | |

2006 USGS photo. The remains of runway 05/23 are visible in the center. | |

| Coordinates | 40°43′32″N 73°35′42″W / 40.72556°N 73.59500°W |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1917 |

| In use | 1917–1961 |

| Garrison information | |

| Occupants | |

Mitchel Air Base and Flight Line | |

| Location | Roughly Charles Lindbergh Blvd., Ellington Ave., East & West Rds., East Garden City, New York |

| Area | 108 acres (44 ha) |

| NRHP reference No. | 100002385 |

| Added to NRHP | May 4, 2018 |

Mitchel Field | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 1918 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Closed | June 25, 1961 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 85 ft / 26 m | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

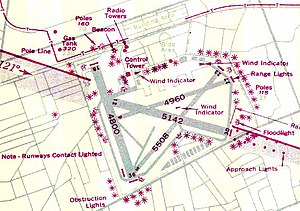

Source: Airfields-Freeman.com [1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Mitchel Air Force Base, also known as Mitchel Field, was a United States Air Force base located on the Hempstead Plains of Long Island, New York, United States. Established in 1918 as Hazelhurst Aviation Field #2, the facility was renamed later that year as Mitchel Field in honor of former New York City Mayor John Purroy Mitchel, who was killed while training for the Air Service in Louisiana.[2]

Decommissioned in 1961, Mitchel Field became a multi-use complex that is home to the Cradle of Aviation Museum, Nassau Coliseum, Mitchel Athletic Complex, Nassau Community College, Hofstra University, and Lockheed. In 2018 the surviving buildings and facilities were recognized as a historic district and listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[3]

History

Origins

During the American Revolutionary War it was known as the Hempstead Plains and used as an Army enlistment center. In the War of 1812 and in the Mexican War, it was a training center for Infantry units. During the American Civil War, it was the location of Camp Winfield Scott. In 1898, in the Spanish–American War, Mitchel's site was known as Camp Black.[4]

World War I

In 1917, Hazelhurst Field #2 was established south of and adjacent to Hazelhurst Field to serve as an additional training and storage base, part of the massive Air Service Aviation Concentration Center. Curtiss JN-4 Jennies became a common sight over Long Island in 1917 and 1918. Hundreds of aviators were trained for war at these training fields, two of the largest in the United States. Numerous new wooden buildings and tents were erected on Roosevelt Field and Field #2 in 1918 in order to meet this rapid expansion.[5]

Between the Wars

Mitchel Field continued to grow after World War I and between 1929 and 1932. An extensive building program was undertaken after the war to turn the temporary wartime facilities into a permanent Army post, with new barracks, warehouses, hangar space, and administrative buildings. Much of this construction still exists today, being used for non-military purposes.

In the 1920s and 1930s, various observation, fighter, and bomber units were stationed at the airfield. It became a major aerodrome for both the Air Corps as well as various civilian activity. The 1920s was considered the golden age of air racing and on 27 November 1920, the Pulitzer Trophy Race was held at Mitchel Field. The race consisted of four laps of a 29 miles (47 km) course. 38 pilots entered and took off individually. The winner was Capt. Corliss Moseley, flying a Verville-Packard VCP-R racer, a cleaned-up version of the Army's VCP-1 pursuit plane, at 156.54 miles per hour (251.93 km/h).[6]

In October 1923, Mitchel Field was the scene of the first airplane jumping contest in the nation. During the same year, two world's airplane speed records were established there. In 1924, the airmail service had its inception in experimental flights begun at the airfield. In September 1929, Lt. Gen. James H. Doolittle, then a Lieutenant, made the world's first blind flight.[7]

In 1938, Mitchel was the starting point for the first nonstop transcontinental bomber flight, made by Army B-18 Bolo bombers.[8] Mitchel Field also served as a base from which the first demonstration of long-range aerial reconnaissance was made. In May 1939, three B-17s, with Lt. Curtis LeMay navigating, flew 620 miles (1,000 km) out to sea and intercepted the Italian ocean liner SS Rex. This was a striking example of the range, mobility, and accuracy of modern aviation at the time.[9][10] On September 21 of that year the base was struck by the "Long Island Express" hurricane. Flooding produced water that was over knee-deep, numerous trees were toppled and the glass was smashed atop the traffic control tower.[11]

World War II

In 1940 Mitchel Field was the location of the Air Defense Command, a command charged with the mission of developing the air defense for cities, vital industrial areas, continental bases, and military facilities in the United States (also known as the "Zone of the Interior"). Later, First Air Force, was given the responsibility for air defense planning and organization along the eastern seaboard. Under its supervision an aircraft patrol system along the coast for observing shipping was placed into operation.[4] During 1943, Mitchel AAF became a staging area for Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers and their crews before being sent overseas.[12]

Mitchel Field was a major source of supply in initial garrisoning and defense of North Atlantic air bases in Newfoundland, Greenland, and Iceland. From the airfield the planning for the air defense of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland was conducted. Antisubmarine patrol missions along the Atlantic coast were carried out in 1942 by the United States Army Air Forces Antisubmarine Command aircraft based at Mitchel.[4]

Under the direction of the First Air Force, Mitchel Army Airfield became a command and control base for both I Fighter and I Bomber Command. Tactical fighter groups and squadrons were formed at Mitchel to be trained at AAF Training Command bases (mostly in the east and southeast) before being deployed to the various overseas wartime theaters. Additionally, thousands of Army Air Force personnel were processed through the base for overseas combat duty. With the end of World War II, returning GIs were processed for separation at Mitchel.[4]

Mitchel aircraft crashes included a P-47 that struck Hofstra University's Barnard Hall on 23 March 1943.[13]

In March 1946, the headquarters of Air Defense Command was established at Mitchel Army Airfield.

United States Air Force

With the establishment of the United States Air Force as a separate service in 1947, Mitchel AAF was redesignated as Mitchel Air Force Base.

In December 1948, ADC's responsibilities were temporarily assumed by the Continental Air Command, (ConAC), also located at Mitchel AFB. ConAC also was responsible for the reorganization of the Air Force Reserve after World War II. In 1949, the reserve mission was assigned to First Air Force, which was also headquartered at Mitchel AFB. First Air Force became the command and control organization for supervising the training of the air reserve in 15 eastern states and the District of Columbia.[4] By 1949, due to the problems associated with operating tactical aircraft in the urban area – the noise, the small size of the field, and safety concerns – Mitchel AFB was relieved of the responsibility for defending New York's air space.[8]

Army Anti-Aircraft Command moved to Mitchel AFB on 1 November 1950.

After Air Defense Command was re-established on January 1, 1951; the 1945 U.S. Air Defense Plan recommendation for "... moving ADC Headquarters from Mitchel Field to a more central location ... in a protected command center" was completed to Ent Air Force Base, Colorado, on 8 January 1951.[14][15] On November 29, 1952, President-elect Dwight D. Eisenhower took off from Mitchel Field on a U.S. Air Force aircraft en route to South Korea, to fulfill a campaign promise.[8][16] Colonel W. Millikan's transcontinental speed record flight of 4 hours, 8 minutes set in a North American F-86 Sabre on 2 January 1954 ended at Mitchel AFB.

In April 1961, flying was halted and the 514th Troop Carrier Wing reassigned to McGuire Air Force Base in New Jersey. After the 514th TCW moved, the base was closed on 25 June 1961. The property was turned over to Nassau County for redevelopment.[5][17][18] The facility still has military housing, a commissary and exchange facilities to support military families and activities in the area. The Garden City–Mitchel Field Secondary, a remnant of the Long Island Rail Road's Central Branch from Garden City to Bethpage, ends in the northern part of Mitchel Field, providing sporadic freight service.

Major commands assigned

- Aviation Section, U.S. Signal Corps, July 1917

- Division of Military Aeronautics, 29 May 1918

- Redesignated: Director of Air Service

- Redesignated: U.S. Army Air Service, 24 May 1918

- Redesignated: U.S. Army Air Corps, 2 July 1926

- General Headquarters (GHQ) Air Force, 1 March 1935

- Northeast Air District, 18 October 1940

- Redesignated: 1st Air Force, 26 March 1941

- Redesignated: First Air Force, 18 September 1942

- Continental Air Forces, 13 December 1944

- Air Defense Command, 21 March 1946

- Continental Air Command, 1 December 1948 – 1 April 1961

- Remained attached to Air Defense Command until 1 January 1951

Major units assigned

|

|

Notes: Records incomplete for units assigned prior to 1940; Air Defense Command (ADC); Air Force Reserve (AFRES) assigned to Continental Air Command (ConAc); 18th Air Force Troop Carrier Wings assigned to Tactical Air Command; Military Air Transport Service (MATS) 1112th Special Air Missions Squadron (SAMS) provided VIP transportation in New York City area for Commanding General, First Army, General Eisenhower and UN Military Staff using VC-47. The SAM mission was taken over by the 1254th Air Transport Group at Bolling AFB with deployed aircraft (1298th ATS, 1299th ATS) to Mitchel.

Source for Major Commands and Major Units assigned:[17][19][21][22][23][24][25]

See also

- Roosevelt Field (airport)

- Nassau Inter-County Express § Mitchel Field Depot

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Hempstead (town), New York

- New York World War II Army airfields

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency

This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency

- ^ Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields: New York, Central Long Island Archived 2007-12-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "History of Mitchel Field, New York". Air Force Historical Research Agency. 1917–1943. p. 511.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places actions for May 4, 2018". U.S. National Park Service. May 4, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Office of Information Services Headquarters Continental Air Command, Mitchel Air Force Base, New York, 26 October 1955 Fact Sheet

- ^ a b The History of Mitchel Field, The Cradle of Aviation Museum Archived 2008-07-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pulitzer Trophy Air Races

- ^ USAFHRA Document 00489043

- ^ a b c Brodsky, Robert (July 30, 2018). "Mitchel Field Air Base added to National Register of Historic Places". Newsday. Archived from the original on July 30, 2018. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ^ Mitchel Field History Document

- ^ Correll, John T. (December 2008). "Rendezvous With the Rex". Air Force Magazine. Vol. 91, no. 12. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011.

- ^ "Streets become Canals in Hurricane: Tide Razes Boardwalk, Piers". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 22, 1938 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ USAFHRA Document 00175652

- ^ Associated Press, "College Building Set Afire by Crash of Army Airplane", The Roanoke World-News, Roanoke, Virginia, Tuesday afternoon, 23 March 1943, Volume 81, Number 70, page 3.

- ^ Schaffel, Kenneth (1991). Emerging Shield: The Air Force and the Evolution of Continental Air Defense 1945-1960 (PDF, 45 MB). General Histories (Report). Office of Air Force History. p. 69. ISBN 0-912799-60-9. Retrieved September 26, 2011.

- ^ compiled by Johnson, Mildred W. (December 31, 1980) [February 1973: Cornett, Lloyd H. Jr]. A Handbook of Aerospace Defense Organization 1946 - 1980 (PDF). Peterson Air Force Base: Office of History, Aerospace Defense Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 13, 2016. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

- ^ Newton, Jim (2012). Eisenhower: The White House Years. New York: Doubleday, p. 77.

- ^ a b USAFHRA Document 00489094

- ^ USAFHRA Organizational Records Branch, 514th Air Mobility Wing Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Maurer, Maurer, ed. (1982) [1969]. Combat Squadrons of the Air Force, World War II (PDF) (reprint ed.). Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-405-12194-6. LCCN 70605402. OCLC 72556.

- ^ Grace, Dr. Timothy M. (2008) Second To None: The History of the 368th Fighter Group

- ^ Air Force Historical Research Agency Organizational Records Branch Archived 2012-02-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ravenstein, Charles A. (1984). Air Force Combat Wings Lineage and Honors Histories 1947–1977. Maxwell AFB, Alabama: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-912799-12-9.

- ^ Maurer, Maurer (1983). Air Force Combat Units Of World War II. Maxwell AFB, Alabama: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-89201-092-4.

- ^ USAFHRA Document 00175687 (2500 ABG/Wing)

- ^ 11 October 1950: 100,000 miles to Bolling