Mirdita

| Part of a series on |

| Albanian tribes |

|---|

|

Mirdita is a region of northern Albania whose territory is synonymous with the historic Albanian tribe of the same name.

Etymology

The name Mirdita derives from a legendary ancestor named Mir Diti from whom the tribe claims descent.[1] Other alternative folk etymologies have been presented. Another folk etymology links the word to the Albanian greeting "mirëdita" meaning hello, "good day".[2]

Geography

Historically Mirdita was the largest tribal region of Albania in terms of geographic spread and population.[3] The region is situated in northern Albania, and it borders the traditional tribal areas of Puka (Berisha, Kabashi, Qerreti) in the north; the Lezha highlands (Vela, Bulgëri, Manatia, Kryeziu) in the west and southwest; the northern Albanian coastal plain of Lezha and Zadrima between the Drin and Mat rivers in the west; the river Mat and region of Mat in the south and the area of the Black Drin river in the east.[4] The traditional areas and settlements of Mirdita are: Bisak, Blinisht, Breg, Doç, Domgjon, Fregna, Gojan, Gomsiqja, Gryka e Gjadrit, Gjegjan, Kaçinar, Kalor, Kashnjet-Kaftali, Kashnjet, Kalivaç, Kalivarja, Kimza, Kisha e Arstit, Korthpula-Kaftalli, Korthpula, Konaj, Kushnen, Lumbardhë, Mesul, Mnela, Ndërfana, Orosh, Qafa e Malit, Rras, Sukaxhia, Sërriqja, Shkoza, Spaç, Shëngjin, Tejkodra, Tuç, Ungrej, Vig, Vrith and Xhuxha.[5]

The current district of Mirdita is located within the Mirdita tribal region that contains the Lesser and Greater Fan rivers.[4] The largest town and administrative centre of the modern period is Rrëshen, and other significant settlements exist in the area such as Rubik, Orosh, Blinisht, Kaçinar, Kalivaç, Kurbinesh, Perlat and Spaç.[4]

- Munella Mountain, Mirdita

- Town centre in Rrëshen, Mirdita

- Rrëshen cathedral, Mirdita

- Fan Valley at Reps, Mirdita

- Durrës-Kukës Highway or Rruga e Kombit (Nation's highway) linking Albania with Kosovo passes through Mirdita

History

Origins

The Mirdita tribe claimed descent from a legendary ancestor named Mir Diti, the son of Dit Miri and the grandson of Murr Deti known also as Murr Dedi.[6] The brother of Mir Diti was Zog Diti, the ancestor of the Shoshi tribe and the Shala tribe were descendants from another brother Mark Diti.[6] The male children of Mir Diti who were Skanda (Skana), Bushi, Qyqa and Lluli (Luli) formed the core of the Kushneni, Oroshi and Spaçi tribal units during the sixteenth century.[6] Overall the Mirdita tribe was more of a federation of different tribal sources with not all fis (clan or tribe) claiming descent from a common male ancestor although the Kushneni, Oroshi and Spaçi and Tusha did trace their origins in those terms.[6] Local Mirdita traditions claim that the Dibrri bajrak is mixed and has southern Albanian Tosk origins.[7]

According to the oral history of tribe, the Mirdita along with the ancestors of the Shala and Shoshi tribes originated from the area of Mount Pashtrik (on the modern Kosovo-Albania border) and lived under a Bulgarian chieftain.[6] In the early history of the Mirdita there exists evidence of Orthodox influence in what later was a Catholic tribe.[6] The arrival of the Ottomans in the region pushed the tribes from Pashtrik toward the westward direction of the mountains.[6] During the time of Skanderbeg around 1450 and after the Ottomans captured Shkodër, the Mirdita fled to their original homeland and returned in 1750 to their present location.[6]

Ottoman period

Mirdita is for the first time cited in 1416 as a surname for 2 families living in the village of Mensabardi which was located very near Shkodër, the patriarchs of these 2 families were Jon Mirdita and Petër Mirdita.[8] Later research done by Milan Šufflay showed that these 2 families migrated from the area of the rivers Mat and Fan where historical Mirdita was located.[9] After this period the word Mirdita is cited as Mirdita in an Ottoman document of 1571 and in a report by Marino Bizzi the tribal name appears as Miriditti in 1610.[4] In a letter from 1621 by Albanian bishop Pjetër Budi it is written as Meredita, in the ecclesiastical reports of Pjetër Mazreku (1634) as Mireditta, bishop Benedetto Orsini Ragusino (1642) as Miriditi and Pietro Stefano Gaspari (1671) as Miriditi.[2] In a 1689 Italian map by cartographer Giacomo Cantelli da Vignola it's noted as Mirediti and an ecclesiastical report of 1703 by archbishop Vićenco Zmajević as Meredita(i).[2] The area of Mirdita was also known earlier by the name Ndërfandina meaning land between the two Fan rivers.[2]

In comparison to other Albanian tribes the military organisation of Mirdita was better developed and they used their forces to resist incursions from the Ottomans and others in the area and also deploying it for pillaging and raiding.[10] In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century they were ruled by kapedan (captain) Prenk Llesh who died fighting the Ottomans and succeeded by his son Prenk Doda Tusha who partook in wars on side of the Ottomans against the Greeks who were fighting for independence.[11] He was succeeded by his younger brother Nikolla Tusha or Kola Doda Tusha whose uncle Llesh i Zi (Black Llesh) took over, a man with a reputation for bravery and cruelty.[11] Llesh i Zi fought with the empire against the Greeks and later in 1830 backed Mustafa Bushati in his fight against them assisting him at the siege of Shkodër until its capture by the Ottomans in November 1831 who exiled him to Yanina.[11] His nephew Nikolla was appointed kapedan and he partook in Ottoman military expeditions against the Montenegrins gaining the admiration and support of Grand Vezir Reşid Mehmed Pasha who appointed him in the imperial vanguard at the battle of Konya against Egyptian forces.[11] The sons of Lleshi i ZI attempted a coup and Nikolla had them murdered leading to a blood feud within the family.[11] By the 1860s, the kapedan of Mirdita was Bib Doda Tusha and ran into difficulties with the Ottoman Empire over an alleged involvement in an uprising and from fellow tribesmen who refused to recognise him as leader after he had not paid them wages for their participation in the Crimean War.[12] Dying in 1868 he was succeeded by his young son Prenk Bib Doda Tusha.[12]

- Malet e Shënjtit (holy mountains) close to Orosh

- The St Alexander church of Orosh in 1903

- Processional cross at the Church of St Alexander in Orosh, Mirdita (1890s)

- Young Mirdita man near a cross (1912)

- The rebuilt new church of Orosh

In the late Ottoman period, the Mirdita tribe were all devoutly Catholic, had 2,500 households and five bajraktars (chieftains).[13][2] In times of war the Mirdita could mobilise up to 5,000 irregular troops when expected by the Ottoman state.[13] A general assembly of the Mirdita met often in Orosh to deliberate on important issues relating to the tribe.[13] The position of hereditary prince of the tribe with the title Prenk Pasha (Prince Lord) was held by the Gjonmarkaj family.[13] Apart from the princely family the Franciscan Abbot held some influence among the Mirdita tribesmen.[13] Within the Sanjak of Shkodër, the Mirdita were fiercely independent and the most powerful tribe of the province.[13] Alexandre Degrand, the French consul who served in Shkodër during the 1890s noted that for the past twenty years only seven outsiders had been to Orosh with one being the Ottoman vali (governor) of the sanjak.[13]

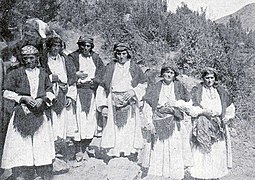

- Women from Mirdita (1890s)

- Men from Mirdita (1890s)

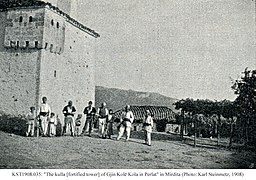

- Kulla (fortified tower house) in Perlat, Mirdita (1908)

- Mirdita male mountain guides and female porters (1908)

- 150 Mirdita fighters enter Durrës to support prince Wied (May 1914)

During the Great Eastern Crisis, Prenk Bib Doda as hereditary chief of the Mirdita initiated a rebellion in mid-April 1877 against government control and the Ottoman Empire sent troops to put it down.[14] Following the revolt Doda was exiled and after the Young Turk Revolution (1908) was allowed home where his return was celebrated by tribesmen and the new government expected him to secure Mirdita support for the Young Turk regime.[15] During the Albanian revolt of 1910, Ottoman forces and their commander Mahmud Shevket Pasha briefly visited Mirdita during their wider campaign to quell the uprising within the region.[16] During the Albanian Revolt of 1911, Terenzio Tocci, an Italo-Albanian lawyer who had spent year with the tribe gathered the Mirditë chieftains on 26/27 April in Orosh and proclaimed the independence of Albania, raised the flag of Albania and declared a provisional government.[17] After Ottoman troops entered the area to put down the rebellion, Tocci fled the empire abandoning his activities.[17]

In the latter half of the 19th century, there was a cholera outbreak in the region of Mirdita, Albania which caused some clan members to migrate elsewhere. At least one Mirdita member fled to what is current day Ulcinj, Montenegro.

Independent Albania

During the Balkan Wars, Albania became independent and Mirdita was included in the new country.[18] Prenk Bib Doda with hopes of claiming the Albanian throne gave strong support to government of Ismail Qemali in Vlorë.[18] After World War One Doda was assassinated in 1919 near the marshes of Lezha and as he was childless, a relative Marka Gjoni claimed the position of kapedan.[18] Many of the Mirdita leaders refused to acknowledge him and he lacked popularity among the tribe due to issues of cowardice shown during the war.[18] By 1921 Marka Gjoni received money from Belgrade and rebelled against the new 'Muslim' Albanian government and he declared a "Mirdita Republic" at Prizren in Yugoslav territory on 17 July 1921.[18] Recognised by Greece and supported by Yugoslavia the attempted statelet was put down by Albanian troops on 20 November 1921.[18] Marka Gjoni fled to Yugoslavia which after some time he was allowed to return to Albania and in Mirdita was active in local affairs for a few years before his death.[18]

His son Gjon Markagjoni became the next kapedan and reached an understanding with the Albanian state, later being given prominent government ministries to lead.[19] During the Second World War he collaborated with Italian and later German military forces occupying Albania and by 1944 fled to Italy.[20] His son became the next kapedan and with his Mirdita fighters later fled to the Luma region continuing an anti-communist struggle.[20] In early 1946 he was killed in his sleep by his brother in law hoping for a reprieve from communist forces who in turn was killed by Mark's brother.[21] Mark's son, Gjon Markagjoni (1938-2003) spent his years in a communist internment camp, as did other members of the Gjonmarkaj family.[22] With the collapse of communism in Albania (1992), the position of Prince of Mirdita or kapedan has become a memory of a long ago past.[22]

In literature

In the English Translation (Robert Elsie, Janice Mathie-Heck) of the Albanian National Epic The Highland Lute by Gjergj Fishta, the Mirdita Tribe, as well as other northern tribes, is mentioned.

The glossary entry for Mirdita is written as:

Northern central Albanian tribe and traditional tribal region. The Mirdita region corresponds broadly to the present District of Mirdita, though, as tribal land, it originally referred more specifically to the mountains north of Blinisht. The name was recorded in 1571 as Mirdita and in 1610 as Miriditti and is often said to be related to Alb. mire dita 'good day,' though this is probably a folk etymology. Mirdita is traditionally a staunchly Catholic region, with its religious centre at the church of Saint Alexander in Orosh."[23]

Ethnography

Traditionally Mirdita consisted of three bajraks (clans or tribes): Kushneni, Oroshi and Spaçi that claimed an origin from a legendary brother of Shoshi and Shala.[5] Being related to the three bajraks they did not practice endogamy with the Shoshi and Shala tribes and instead intermarried with the Dibrri and Fani bajraks. Together these bajraks of Dibrri, Fani, Kushneni, Oroshi and Spaçi composed the larger Mirdita tribal unit.[3] The Mirdita tribe had a flag with a white hand upon a red background and the five fingers represented the bajraks.[5] During 1818, the bajraks of Ohri i Vogël (Little Ohri) composed of Bushkashi, Kthella and Selita seceded from the Mat tribal region located south of Mirdita and four bajraks of Rranza, Manatia, Bulgëri and Vela from the Lezha highlands.[5] Altogether after 1818 the Mirdita tribal region was made up of twelve bajraks.[5]

During the First World War occupation of Albania, Austro-Hungarian authorities conducted the first reliable census (1918) of the area and Mirdita had 2,376 households and 16,926 inhabitants.[24]

References

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 214, 222.

- ^ a b c d e Elsie 2015, p. 214.

- ^ a b Elsie 2015, pp. 213, 219.

- ^ a b c d Elsie 2015, p. 213.

- ^ a b c d e Elsie 2015, p. 219.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Elsie 2015, p. 222.

- ^ Elsie 2015, p. 240.

- ^ Regjistri i Kadastrës dhe i Koncensioneve për rrethin e Shkodrës 1416-1417, përgatitur nga Injac Zamputti, Tiranë: Akademia e Shkencave e Republikës Popullore Socialiste të Shqipërisë, Instituti i Historisë, 1977. p. 280.

- ^ Shuflaj M., Serbë dhe shqiptarë, përkthyer nga Hasan Çipuri, Tiranë: Toena, 2004,p.82, ISBN 99927-1-854-4

- ^ Elsie 2015, p. 221.

- ^ a b c d e Elsie 2015, p. 227.

- ^ a b Elsie 2015, p. 228.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gawrych 2006, p. 32.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 40.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 160.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 178.

- ^ a b Gawrych, George (2006). The crescent and the eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. p. 186. ISBN 978-1-84511-287-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Elsie 2015, p. 232.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 232–233.

- ^ a b Elsie 2015, p. 233.

- ^ Elsie 2015, pp. 233–234.

- ^ a b Elsie 2015, p. 234.

- ^ Fishta, Elsei, Mathie-Heck, Gjergj, Robert, Janice (2005). The Highland Lute. I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd. p. 443. ISBN 1-84511-118-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Elsie, Robert (2015). The Tribes of Albania: History, Society and Culture. I.B.Tauris. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-85773-932-2.