Milton, Massachusetts

Milton, Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

Milton Post Office | |

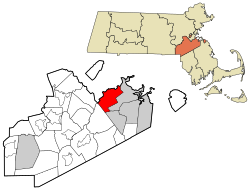

Location in Norfolk County in Massachusetts | |

| Coordinates: 42°15′00″N 71°04′00″W / 42.25000°N 71.06667°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Norfolk |

| Settled | 1640 |

| Incorporated | 1662 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Representative town meeting |

| • Town Administrator | Nicholas Milano |

| Area | |

• Total | 34.4 km2 (13.3 sq mi) |

| • Land | 33.8 km2 (13.0 sq mi) |

| • Water | 0.6 km2 (0.2 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 40 m (130 ft) |

| Population (2020)[1] | |

• Total | 28,630 |

| • Density | 830/km2 (2,200/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP Code | 02186 |

| Area code(s) | 617 and 857 |

| FIPS code | 25-41690 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0619459 |

| Website | www.townofmilton.org |

Milton is a town in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States, and a suburb of Boston. The population was 28,630 at the 2020 census.[1]

Milton is located in the relatively hilly area between the Neponset River and Blue Hills, bounded by Brush Hill to the west, Milton Hill to the east, Blue Hills to the south and the Neponset River to the north. It is also bordered by Boston's Dorchester and Mattapan neighborhoods to the north and its Hyde Park neighborhood to the west; Quincy to the east; Randolph to the south, and Canton to the west.

History

Indigenous peoples

The area now known as Milton was inhabited for more than ten thousand years prior to European colonization. The Paleoamerican archaeological site Fowl Meadows lies within the bounds of present-day Milton, with charcoal remains dated to 10,210±60 years before present in 1994, later calibrated to 12,140 years before present.[2]

At the time of European exploration and settlement in the early 1600s, the area was inhabited by the Neponset tribe of the Massachusett, an Algonquian people,[3] who referred to the area that would become Milton as 'Unquatiquisset,' meaning 'Lower Falls', denoting the place where the rapids of the Neponset River meet Massachusetts Bay.[4]

According to local traditions and 19th-century accounts, several Native American graves and ceremonial pits may have been uncovered during construction along Canton Avenue in Milton. These discoveries, which were reported in local newsletters and oral histories, are believed to have belonged to members of the Ponkapoag tribe, who historically inhabited the area. Graves found during roadwork were said to have been oriented east to west, potentially reflecting cultural or religious practices of the tribe. Nearby pits, possibly used for cooking or religious ceremonies, were also reported, and evidence of long-term use, such as fire-scorched rocks and charcoal, was observed.[5]

The namesake of the Massachusett people was the indigenous name for the Great Blue Hill, Massachusett meaning 'at the great hill'. The hills had a religious significance to the Massachusett, who extensively mined rhyolite to make weaponry thought to be imbued with divine strength from the sacred hills. [6]

Local residents have also shared anecdotal reports of finding arrowheads and other Native American artifacts in the area throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, further corroborating the area’s long-standing significance to Indigenous peoples.[7]

The Ponkapoag tribe largely resided in the surrounding areas, including Canton and Stoughton, though some members, such as Mingo and his descendants, are recorded as having lived in Milton well into the 18th century.

English colonization

The area that became Milton began to be sparsely settled by English colonists in the late 1620s and early 1630s as a part of Dorchester, formally established as an organized settlement in 1640 by Puritans from England. Richard Collicott, one of the first English settlers, built a trading post near the Neponset River, and negotiated the purchase of Milton from Sachem Cutshamekin. John Eliot, an English missionary, published a Massachusett translation of the Bible in 1640, facilitating rapid conversion of indigenous inhabitants to convert to Christianity and assimilate to the ideologies and culture of the colonists.

Many of the initial English settlers arrived during the 1650s, fleeing the aftermath of Oliver Cromwell's deposition from power and the English Civil War.[8]

Several early Puritan families of Milton would later become influential in the culture and politics of Massachusetts Bay Colony, these families including the Sumners, Houghtons, Hutchinsons, Stoughtons, Tuckers, Voses, Glovers, and Babcocks.[9] The original name for the area, translated to "Lower Falls" was adapted as "Lower Mills" after the establishment of Israel Stoughton's Grist Mill in 1634, the earliest mill in the United States. Furthermore, in 1640, English settlers began shipbuilding at Gulliver's Creek, a tributary of the Neponset, using the innumerable quantity of Eastern white pines found in early Milton's dense forests.[10]

In 1662, "that part of the Town of Dorchester which is situated on the south side of the Neponset River commonly called 'Unquatiquisset' was incorporated as an independent town and named Milton in honor of Milton Abbey, Dorset, England."

After incorporation, the population continued to increase during the late 17th century in the wake of King Philip’s War which had devastated much of New England. The town was unscathed by the war due to several factors including the strategic location between hills, proximity to the well fortified capital Boston and most notably, the effective decimation of the indigenous inhabitants of the area by the 1660s as a result of disease and violent encroachment by colonists and the pacification of surviving Massachusett via mass conversions to Christianity and relocation to praying towns. Those who did resist were swiftly executed or sent to the West Indies as slaves. By the 1670s, the threat of violent resistance from the Massachusett was effectively eliminated, affording the developing town comparative safety and consequent prosperity compared to other regions of New England. As a result of this, colonists fleeing the villages and towns destroyed in the war settled in the town, establishing farms and nascent industries. This wave of migration from the rest of the colony marked the settlement of several prominent families in the town. For example, Ralph Houghton, a Puritan from England who had helped establish the town of Lancaster fled to Milton with his family after Lancaster was destroyed by the indigenous Nashua people who razed the town and massacred almost every inhabitant during the war. The Houghton family would later become prominent not just in Milton, but Massachusetts as a whole.

A powder mill established in 1674 may have been the earliest powder mill in the colonies, taking advantage of the town's water power sites. Boston investors, seeing the potential of the town and its proximity to the city, provided the capital to develop 18th-century Milton as an industrial area, including an iron slitting mill and sawmills, and the first chocolate factory in New England (the Walter Baker Chocolate Factory) in 1764, which was converted from the old Stoughton Grist Mill. Through the efforts of Daniel Henchman the first paper mill to appear in New England was at Milton on the Neponset River in 1729. From its earliest days, Milton's favorable location at the rapids of the Neponset River made it one of the earliest and most active industrial areas in the United States.[11][12]

The Suffolk Resolves, one of the earliest attempts at negotiations by the American colonists with the British Empire were signed in Milton in 1774, and were used as a model by the drafters of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. The Suffolk Resolves House, where the Resolves were passed, still stands and it is maintained as the headquarters of the Milton Historical Society. At the time of the Resolves it was owned by Capt. Daniel Vose, a well-known businessman, and later a representative to the Provincial Congress.[13] The house was moved to a new location at 1370 Canton Avenue in Western Milton in order to save it from demolition at its previous location in "Milton Village" at Lower Mills. They were the "Suffolk Resolves" because Milton was part of Suffolk County until 1793, when Norfolk County split off, leaving only Boston and Chelsea in Suffolk County.

Milton became an active site for important power players in colonial Massachusetts. John Hancock purchased a large hill, today called Hancock Hill, in the Blue Hills Reservation and planted orchards as well as harvested wild blueberries which grow abundantly at the summit. Two royal governors of Massachusetts, Jonathan Belcher and Thomas Hutchinson, had houses in Milton. The Governor Belcher House dates from 1777, replacing the earlier home destroyed by a fire in 1776, and it is privately owned on Governor Belcher Lane in East Milton.

Thomas Hutchinson maintained a summer estate called Unquity at the peak of Milton Hill, and during the increasingly violent revolutionary insurrections in Boston, he fled to Milton after his townhouse in the North End was burned by a mob and he was driven from the city after citizens learned he supported the suppression of Massachusetts by the British following the Boston Tea Party. Although Hutchinson's mansion house was demolished in 1947, Governor Hutchinson's Field, owned by the Trustees of Reservations today is a meadow on Milton Hill, with a view of the Neponset River estuary and the skyscrapers of Boston six miles (10 km) away. Both the neighboring house in which Hutchinson lived during the construction of his mansion and the barn of the estate still stand and are both privately owned. The last remnant of Unquity is the ha-ha wall, once a part of the estate's opulent gardens. Both Governor Belcher's house and Governor Hutchinson's field are on the National Register of Historic Places.

After American independence

Following the revolution, Milton continued to be a thriving agricultural and industrial town, greatly influenced both socially and economically by the prosperity of Boston and the newly-forged American identity.

The town grew extremely wealthy in the late 18th and early 19th century with the booming China Trade and the industrialization of Massachusetts during the early Industrial Revolution. As a result, much of Boston's elite built opulent country estates set on vast grounds throughout the idyllic hills and meadows of the town's more rural sections. Like many other coastal American cities, high society would leave the cities for the summer, and in the case of Boston, many would move to Milton due to its rural qualities, proximity to Boston, its highly active mercantile wharf, and the families' factories in Lower Mills which allowed the tycoons to continue business in the summer months. Most of these estates were concentrated on Milton Hill, Brush Hill, and Upper Canton Avenue. Among the last remaining of these estates that is entirely intact is the W.E.C Eustis Estate at the base of the Blue Hills on Canton Avenue.

The town was also home to America's first piano factory. Revolutionary Milton is the setting of the opening of the 1940 bestselling historical novel Oliver Wiswell by Kenneth Roberts. The Blue Hill Meteorological Observatory is located in the town, home of the nation's oldest continuously kept meteorological records.[14]

The Granite Railway passed from granite quarries in Quincy to the wharf of Milton on the Neponset River, beginning in 1826. It is often called the first commercial railroad in the United States, as it was the first chartered railway to evolve into a common carrier without an intervening closure. A centennial historic plaque from 1926 and an original switch frog and section of track from the railway can be found in the gardens on top of the Southeast Expressway (Interstate 93) as it passes under East Milton Square. The frog had been displayed at the Chicago World's Fair in 1893.[15]

East Milton Square developed as a direct result of the Granite Railway. Quincy granite was seen as of remarkably high quality, and there was an incredibly high demand for it not only in Boston but abroad. Four sheds in East Milton were used to dress the raw granite stone prior to it being brought by rail to the wharf for transfer to boats to send the stones to the Port of Boston to be sent abroad. East Milton Square was originally termed the "Railway Village" and a train station was located there after 1871 when the Granite Railway became a passenger line of the Old Colony Railroad. The Blue Bell Tavern, which was also a hotel, served as the headquarters of the Granite Railway and it was later named the Russell House. It was located on the site of the current United States Post Office in East Milton Square.

In 1801 Josiah Bent began a baking operation in Milton, selling "water crackers" or biscuits made of flour and water that would not deteriorate during long sea voyages from the Port of Boston. A crackling sound occurred during baking, hence the common American term "cracker". His company later sold the original hardtack crackers used by troops during the American Civil War due to their low potential for spoil. The company, Bent's Cookie Factory, is still located in Milton and continues to sell these items to Civil War reenactors and others. However, the original 1801 mill has been turned into residential and commercial space.

Robert Bennet Forbes, a descendant of an old Massachusetts family, was a noted China Trade merchant, sea captain, and philanthropist during the Irish Famine, supporting the large influx of Irish immigrants in Boston despite the elites' distaste for the immigrants. He built a Greek Revival mansion in 1833 at 215 Adams Street on Milton Hill, adjacent to the former site of Thomas Hutchinson's estate. As a prominent example of Greek Revival architecture and possessing many artifacts from the China Trade period, the Captain Robert Bennet Forbes House is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is open for tours. The museum's grounds include a log cabin replica and a collection of Lincoln memorabilia acquired by the daughter of Forbes as a result of her adoration and admiration of Abraham Lincoln.

Milton adopted restrictive zoning regulations in 1913, which were pushed by anti-immigration crusaders and proponents of eugenics.[16] The restrictive regulations sought to prohibit the kind of housing affordable to immigrants and minorities, which would serve to keep undesirable groups out of the town.[16] In 1937, the town adopted a more restrictive zoning regulation to prevent smaller units of housing.[16]

During the mid to late 20th century, the character of the town changed from that of agriculture, industry, and rural retreat for the wealthy to suburban. The population of the town exploded following World War II as the suburbs of America grew rapidly. By the 1950s, many of the big estates were broken into subdivisions as the town's residential growth continued to this day.

George Herbert Walker Bush was born at 173 Adams Street on Milton Hill on June 12, 1924. He became the 41st President of the United States, serving from 1989 to 1993, and his son would become the 43rd President. Coincidentally, Adams Street is named for the family of Presidents John Adams and John Quincy Adams, who lived on the same street just a few miles southeast in Quincy, Massachusetts. The 19th-century Victorian house where President Bush was born is now privately owned and not open to the public.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 13.3 sq mi (34.4 km2), of which 13.1 sq mi (33.8 km2) is land and the balance is water. As a result of its glacial geological history, many kettle ponds dot the town.

There are no official wards or neighborhoods defined in the town's governance and community planning processes.[17]

Climate

Milton, as with most of Massachusetts and New England, has a warm-summer humid continental climate with hot, humid summers, severely cold, snowy winters, mild, wet springs and chilly, brisk falls. It is also often cited as being the windiest city in the United States, with an annual average wind speed of 15.4 mph (24.8 km/h) measured at the Blue Hill Meteorological Observatory.[18][19][20]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °F (°C) | 68 (20) |

71 (22) |

89 (32) |

94 (34) |

96 (36) |

99 (37) |

100 (38) |

101 (38) |

99 (37) |

88 (31) |

81 (27) |

74 (23) |

101 (38) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 56.6 (13.7) |

56.9 (13.8) |

65.6 (18.7) |

79.4 (26.3) |

87.3 (30.7) |

90.0 (32.2) |

92.9 (33.8) |

91.3 (32.9) |

86.9 (30.5) |

77.6 (25.3) |

68.4 (20.2) |

60.0 (15.6) |

94.7 (34.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 34.7 (1.5) |

37.0 (2.8) |

44.1 (6.7) |

56.3 (13.5) |

66.8 (19.3) |

75.4 (24.1) |

81.7 (27.6) |

80.2 (26.8) |

72.7 (22.6) |

61.0 (16.1) |

50.1 (10.1) |

40.2 (4.6) |

58.4 (14.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 26.5 (−3.1) |

28.2 (−2.1) |

35.5 (1.9) |

47.1 (8.4) |

58.5 (14.7) |

66.5 (19.2) |

72.7 (22.6) |

71.4 (21.9) |

64.2 (17.9) |

52.5 (11.4) |

42.0 (5.6) |

32.5 (0.3) |

49.8 (9.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 18.3 (−7.6) |

19.5 (−6.9) |

26.9 (−2.8) |

37.9 (3.3) |

48.2 (9.0) |

57.6 (14.2) |

63.8 (17.7) |

62.6 (17.0) |

55.6 (13.1) |

44.0 (6.7) |

33.8 (1.0) |

24.9 (−3.9) |

41.1 (5.1) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 0.0 (−17.8) |

3.1 (−16.1) |

10.1 (−12.2) |

26.7 (−2.9) |

37.5 (3.1) |

45.9 (7.7) |

54.9 (12.7) |

53.4 (11.9) |

42.3 (5.7) |

30.5 (−0.8) |

19.6 (−6.9) |

8.7 (−12.9) |

−2.5 (−19.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −14 (−26) |

−21 (−29) |

−5 (−21) |

6 (−14) |

27 (−3) |

36 (2) |

44 (7) |

39 (4) |

28 (−2) |

21 (−6) |

5 (−15) |

−19 (−28) |

−21 (−29) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.50 (114) |

4.00 (102) |

5.52 (140) |

4.76 (121) |

3.82 (97) |

4.63 (118) |

3.47 (88) |

3.91 (99) |

4.06 (103) |

5.49 (139) |

4.31 (109) |

5.39 (137) |

53.86 (1,367) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 18.6 (47) |

18.2 (46) |

15.0 (38) |

2.8 (7.1) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.7 (1.8) |

1.8 (4.6) |

12.6 (32) |

69.7 (176.5) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 10.6 (27) |

11.5 (29) |

9.8 (25) |

2.6 (6.6) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

1.3 (3.3) |

7.7 (20) |

17.1 (43) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 13.2 | 11.3 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 13.0 | 12.1 | 10.5 | 10.2 | 9.2 | 11.5 | 10.9 | 12.6 | 139.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 8.1 | 7.1 | 5.7 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 5.3 | 29.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 132.1 | 146.7 | 174.0 | 185.6 | 220.2 | 231.8 | 258.1 | 242.5 | 204.1 | 182.1 | 133.3 | 125.9 | 2,236.4 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 46.3 | 50.9 | 48.5 | 47.9 | 50.4 | 52.7 | 58.0 | 58.7 | 56.7 | 55.1 | 47.0 | 45.9 | 51.5 |

| Source 1: NOAA[21][22] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: BHO[23] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 2,241 | — |

| 1860 | 2,669 | +19.1% |

| 1870 | 2,683 | +0.5% |

| 1880 | 3,206 | +19.5% |

| 1890 | 4,278 | +33.4% |

| 1900 | 6,578 | +53.8% |

| 1910 | 7,924 | +20.5% |

| 1920 | 9,382 | +18.4% |

| 1930 | 16,434 | +75.2% |

| 1940 | 18,708 | +13.8% |

| 1950 | 22,395 | +19.7% |

| 1960 | 26,375 | +17.8% |

| 1970 | 27,190 | +3.1% |

| 1980 | 25,860 | −4.9% |

| 1990 | 25,725 | −0.5% |

| 2000 | 26,062 | +1.3% |

| 2010 | 27,003 | +3.6% |

| 2020 | 28,630 | +6.0% |

| 2022* | 28,364 | −0.9% |

| * = population estimate. Source: United States census records and Population Estimates Program data.[24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34] | ||

As of the census[35] of 2010, there were 27,002 people, 9,274 households, and 6,835 families residing in the town. The racial makeup of the town was 77.4% White, 14.3% Black or African American, 0.1% Native American, 4.1% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, 0.6% from other races, and 2.5% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.3% of the population.

As of the census[35] of 2000, the population density was 1,999.1 inhabitants per square mile (771.9/km2). There were 9,161 housing units at an average density of 702.7 per square mile (271.3/km2).

The top six ancestries of Milton are Irish (38.0%), Italian (11.3%), English (8.6%), West Indian (4.8%), and German (4.7%).

Milton also has been cited as having the highest percentage of residents citing Irish lineage of any town in the United States per capita—38%.[36]

There were 8,982 households, out of which 37.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 60.1% were married couples living together, 11.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 24.8% were non-families. Of all households 21.2% were made up of individuals, and 12.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.79 and the average family size was 3.27.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 25.8% under the age of 18, 8.0% from 18 to 24, 25.9% from 25 to 44, 24.1% from 45 to 64, and 16.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 84.2 males.

According to a 2010 estimate,[37] the median income for a household in the town was $103,373, wealthy compared to Massachusetts and the United States as a whole. The median income for a family was $131,025. Males had a median income of $85,748 versus $61,500 for females. The per capita income for the town was $47,589. About 1.6% of families and 2.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 2.2% of those under age 18 and 4.5% of those age 65 or over.

With a mean house price of $1.02 million, it has one of the highest costs of living in Massachusetts and the United States more generally.[38] 78% of the housing units in Milton are single-family homes. The town has few renters: 82% of the housing is owner-occupied.[16] Home construction dramatically slowed in Milton after the 1960s.[16] Nearly all housing in the town was built before 2000.[16]

Arts and culture

Government

After incorporation, Milton was governed by an open town meeting until 1928. In 1927, citizens voted to adopt a representative town meeting form of government.[39] Voters elect 279 representatives, divided among ten precincts, to three year terms in the town's legislative branch.[40] The town's executive branch is made up of a five-member Select Board and a town administrator.[41][42]

Housing policy

Local politicians in Milton have opposed construction of affordable housing such as apartment buildings, and have supported Milton's single-family zoning regulations apartment construction difficult.[16]

The town was sued by Massachusetts Attorney General Andrea Campbell after Milton voters voted in a February 2024 special election for the town to violate Massachusetts state law on housing and not comply with state law to permit multi-family housing near MBTA stations.[43][44][45][46]

In 1701, Colonial Governor William Stoughton gifted 40 acres (16 ha) of land to Milton to be used "for the benefit of the poor." In the 2010s, Milton rejected proposals to build affordable housing on the land, and sold it for single-family home construction.[43] Local politicians also objected to building affordable housing on a remaining 4 acres (1.6 ha) of vacant land.[43]

Education

There are six public schools in Milton, including four elementary schools: Collicot, Cunningham, Glover, and Tucker; one middle school, Pierce Middle School; and a public high school, Milton High School. Milton is one of the few school systems in the United States to offer a French immersion program, starting in grade 1.[47]

Private schools include Milton Academy, Fontbonne Academy, Thacher Montessori School, Carriage House School, and Delphi Academy. Catholic schools include St. Mary of the Hills School and St. Agatha's School.

Curry College, a small liberal arts institution, is located here.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Milton lies within the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority district. Fixed-route service includes the Mattapan Line, a light rail extension of the Red Line. Milton has 4 stops: Milton, Central Avenue, Valley Road, and Capen Street. This was originally a steam railway prior to becoming a trolley line. Massachusetts Route 28 and Massachusetts Route 138 run north and south across Milton, and Interstate 93, which is also U.S. Route 1 and Massachusetts Route 3, loops around the town near the southern and eastern borders.[48]

Cycling is a popular form of transportation and recreation in Milton. The opening of the Neponset River Greenway reconnected Milton with Boston Harbor via Port Norfolk, Dorchester. Other cycling routes and locations include Turner's Pond, Brook Road, Blue Hills Parkway, Milton Cemetery, and the Pine Tree Brook greenway.[49]

The Milton Yacht Club began in 1902, with a small building in the Lower Mills area beside the Neponset River that was formerly the police department for the town of Milton. Various boats continue to be anchored there or stored on the dock during the winter.

Notable people

- Sophia French Palmer, Nurse, first editor-in-chief of the American Journal of Nursing, and health administrator

- Dana Barros, NBA player, Boston Celtics, Seattle SuperSonics

- Jonathan Belcher, governor of Massachusetts Bay, New Hampshire, and New Jersey Provinces

- Josiah Bent, manufacturer, founder of G.H. Bent Company Factory

- Tim Bulman, Boston College and NFL player, was born in Milton

- George H. W. Bush, 41st President of the United States, was born in Milton

- Brian Camelio, record producer, musician, and entrepreneur

- Ken Casey, bassist and co-lead vocalist of Celtic punk rock group Dropkick Murphys

- Chris Cleary, professional soccer player

- Hal Clement, science-fiction writer

- Jill Ker Conway, Australian-born novelist

- Stephen Davis, music journalist and biographer[50]

- T. S. Eliot, poet, was a student at Milton Academy

- William Ralph Emerson, known for shingle style architecture

- Jim Fahey, NHL player, New Jersey Devils

- Thomas Flatley, real-estate developer

- Elbie Fletcher, All-Star first baseman for Pittsburgh Pirates

- John Ferruggio, led evacuation of Pan Am Flight 93 in 1970[51]

- John Murray Forbes, railroad magnate, merchant, philanthropist and abolitionist

- Robert Bennet Forbes, sea captain, China merchant, ship owner, and writer

- Buckminster Fuller, architect and futurist; born in Milton

- George V. Higgins, attorney, crime novelist, The Friends of Eddie Coyle

- Rich Hill, pitcher for thirteen MLB teams; was born in Milton

- Thomas Hutchinson, 18th Century governor of Massachusetts Bay province

- Abigail Johnson, president of Fidelity Investments

- Charles C. Johnson, far-right political activist

- Edward Johnson III, businessman

- Howard Deering Johnson, restaurateur, founder of Howard Johnson's franchising

- Trish Karter, entrepreneur

- Jordan Knight, singer for band New Kids on the Block

- Janet Langhart, model and journalist

- Johnny Martorano, Winter Hill Gang member

- Jidenna Theodore Mobisson, attended Milton Academy

- Charles Munch, music director of Boston Symphony Orchestra[52]

- Kate O'Neill, distance runner

- William Ordway Partridge, sculptor, poet, and author

- Deval Patrick, former Governor of Massachusetts, attended Milton Academy

- Diane Patrick, former First Lady of Massachusetts[53]

- Everett P. Pope, Medal of Honor recipient; born in Milton

- Mike Ryan, NHL player, Buffalo Sabres

- William Saltonstall, eighth principal of Phillips Exeter Academy

- Jenny Slate, comedian on Saturday Night Live

- Jen Statsky, TV writer and comedian

- Margaret Sutermeister (1875–1950), photographer

- Luis Tiant, former Boston Red Sox pitcher

- Steve Trapilo, former NFL player for New Orleans Saints

- Ronan Tynan, Irish tenor[54]

- Mark Vonnegut, writer, son of author Kurt Vonnegut

- Roger Vose, U.S. Representative from New Hampshire

- Barry Wood, Harvard quarterback in College Football Hall of Fame; born in Milton

- Keith Yandle, NHL player, Florida Panthers; born in Milton

- Matt Duffy, former MLB and NPB Player for Houston Astros and the Chiba Lotte Marines; born and lives in Milton

Notes

"TOTAL POPULATION Survey/Program: Decennial Census, Years: 2010, U.S. Census Bureau." Retrieved 2020-06-03 https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=population%20milton,%20ma&g=1600000US2541725&hidePreview=false&tid=DECENNIALSF12010.P1&vintage=2018&layer=VT_2018_160_00_PY_D1&cid=DP05_0001E

References

- ^ a b "Census - Geography Profile: Milton town, Norfolk County, Massachusetts". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Chandler, Jim (Fall 2001). "On the Shore of a Pleistocene Lake: The Wamsutta Site (19-NF-70)". Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society. 62 (2): 57–58.

- ^ Bragdon, Native People of Southern New England, pp. 66, 72, 104, 112.

- ^ General Court of Massachusetts Bay Colony

- ^ "Milton Historical Society - Milton Journal, Milton Massachusetts". www.miltonhistoricalsociety.org. Retrieved October 3, 2024.

- ^ "The Blue Hills: Archaeological Wonder of Epic Proportions | Friends of the Blue Hills".

- ^ "Milton Historical Society - Milton Journal, Milton Massachusetts". www.miltonhistoricalsociety.org. Retrieved October 3, 2024.

- ^ "About the Town of Milton". Archived from the original on August 13, 2006. Retrieved August 14, 2006.

- ^ "About the Town of Milton". Archived from the original on August 13, 2006. Retrieved August 14, 2006. Town of Milton

- ^ "A History of the Neponset River and Its Tributaries".

- ^ Wroth, 1938, p. 137

- ^ Weeks, 1916, p. 19

- ^ The Story of the Suffolk Resolves, c.1973, Milton, Massachusetts Historical Commission; 60 pgs: http://www.miltonhistoricalsociety.org/DigitalArchives/1973%20The%20Story%20of%20the%20Suffolk%20Resolves.pdf

- ^ Blue Hill Meteorological Observatory

- ^ "The First Railroad in America". Archived from the original on January 8, 2009. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Milton home prices: A Boston Globe Spotlight Team report on the housing crisis". Boston Globe. 2023.

- ^ Town of Milton website Archived August 13, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Van Riper, Tom. "America's Wildest Weather Cities". Forbes. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ "Welcome to nginx!". voices.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on February 17, 2013. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ "Wind- Average Wind Speed- (MPH)". Archived from the original on March 10, 2009. Retrieved April 18, 2009.

- ^ "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS Boston". National Weather Service. Retrieved October 31, 2024.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Blue Hill COOP, MA". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ "Blue Hill Observatory daily sunshine data". Blue Hill Meteorological Observatory. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- ^ "Total Population (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1". American FactFinder, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. 2010.

- ^ "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21-5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1870 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1872. Pages 217 through 220. Table IX. Population of Minor Civil Divisions, &c. Massachusetts. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1860 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1864. Pages 220 through 226. State of Massachusetts Table No. 3. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1850 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1854. Pages 338 through 393. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2022". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ ePodunk Irish Index

- ^ United States Census

- ^ "Milton, MA Housing Market: 2024 Home Prices & Trends".

- ^ "1927 Chap. 0027. An Act To Erect And Constitute In The Town Of Milton Representative Town Government By Limited Town Meetings". archives.lib.state.ma.us. Secretary of the Commonwealth. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ "Town Meeting Members". townofmilton.org. Town of Milton, Massachusetts. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ "Town of Milton, Massachusetts". MMA.org. Massachusetts Municipal Association. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ "Town Administrator". townofmilton.org. Town of Milton, Massachusetts. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ a b c "On four acres left centuries ago to 'the poor,' Milton fights another battle over housing". The Boston Globe. 2024.

- ^ "Milton voters reject new housing plan, violating the MBTA Communities Act". GBH. February 15, 2024.

- ^ "After fierce debate, Milton voters overturn state-mandated housing plan - The Boston Globe". BostonGlobe.com. 2024.

- ^ "Milton voters reject multifamily rezoning plan". WBUR. February 15, 2024.

- ^ "French Immersion Program in the Milton Schools" (PDF). Milton Public Schools. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 26, 2023.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2006. Retrieved March 1, 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Neponset River Greenway". Archived from the original on February 3, 2004. Retrieved February 3, 2004.

- ^ Caleb Daniloff, "Rock from Axl to Zep" Archived October 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, BU Today, October 21, 2008.

- ^ Marquard, Bryan (June 22, 2010). "John Ferruggio, at 84; hero of 1970 Pan Am hijacking". Boston Globe. Retrieved June 27, 2010.

- ^ Holoman, D. Kern (2012). Charles Munch. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199912575.

- ^ Wagness, Lisa (June 25, 2006). "Diane Patrick lends her voice, personal touch". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on September 18, 2006. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ "Famous folks from Milton". Boston Globe. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- Massachusetts Observed Climate Normals (1981–2010)

- The History of Milton, Mass., 1640–1887 by Albert Kendall Teele, published 1886, 688 pages.

- Milton Records: Births, Marriages and Deaths, 1662–1843. Published 1900.

- Dutton, E.P. Chart of Boston Harbor and Massachusetts Bay with Map of Adjacent Country. Published 1867. A good map of roads and rail lines around Milton including the Granite Railroad.

- Old USGS Maps of Milton area.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20081013100415/http://www.muninetguide.com/schools/MA/Milton/Tucker/

- https://web.archive.org/web/20080907194054/http://www.muninetguide.com/schools/MA/Milton/Collicot/

- https://www.townofmilton.org/people/michael-d-dennehy

- Weeks, Lyman Horace (1916). A history of paper-manufacturing in the United States, 1690–1916. New York, The Lockwood trade journal company.

- Wroth, Lawrence C. (1938). The Colonial Printer. Portland, Me., The Southworth-Anthoensen press.