Kurt Schwitters

Kurt Schwitters | |

|---|---|

Schwitters in London, 1944 | |

| Born | Kurt Hermann Eduard Karl Julius Schwitters 20 June 1887 |

| Died | 8 January 1948 (aged 60) Kendal, England |

| Education | Dresden Academy |

| Known for | Dancing, collage, artist's book, installation, sculpture, poetry |

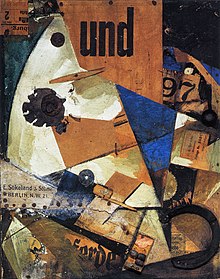

| Notable work | Das Undbild, 1919 |

| Movement | Merz |

Kurt Hermann Eduard Karl Julius Schwitters (20 June 1887 – 8 January 1948) was a German artist. He was born in Hanover, Germany, but lived in exile from 1937.

Schwitters worked in several genres and media, including Dadaism, constructivism, surrealism, poetry, sound, painting, sculpture, graphic design, typography, and what came to be known as installation art. He is most famous for his collages, called "Merz Pictures".

Early influences and the beginnings of Merz, 1887–1922

Hanover

Kurt Schwitters was born on 20 June 1887 in Hanover, at Rumannstraße No.2, now No.8,[1][2][3][4] the only child of Eduard Schwitters and his wife Henriette (née Beckemeyer). His father was (co-)proprietor of a ladies' clothes shop. The business was sold in 1898, and the family used the money to buy some properties in Hanover, which they rented out, allowing the family to live off the income for the rest of Schwitters' life in Germany. In 1893, the family moved to Waldstraße (later renamed to Waldhausenstraße), future site of the Merzbau. In 1901, Schwitters suffered his first epileptic seizure, a condition that would exempt him from military service in World War I until late in the war, when conscription was loosened.

After studying art at the Dresden Academy alongside Otto Dix and George Grosz, (although Schwitters seems to have been unaware of their work, or indeed of contemporary Dresden artists Die Brücke[5]), 1909–1915, Schwitters returned to Hanover and started his artistic career as a Post-Impressionist. In 1911 he took part in his first exhibition, in Hanover. As the First World War progressed his work became darker, gradually developing a distinctive expressionist tone.

Schwitters spent the last one-and-a-half years of the war working as a drafter in a factory just outside Hanover. He was conscripted into the 73rd Hanoverian Regiment in March 1917, but exempted on medical grounds in June of the same year. By his own account, his time as a draftsman influenced his later work, and inspired him to depict machines as metaphors of human activity.

"In the war [at the machine factory at Wülfen] I discovered my love for the wheel and realized that machines are abstractions of the human spirit."[6]

He married his cousin Helma Fischer on 5 October 1915. Their first son, Gerd, died within a week of birth, 9 September 1916; their second, Ernst, was born on 16 November 1918, and was to remain close to his father for the rest of his life, up to and including a shared exile in Britain together.

In 1918, his art was to change dramatically as a direct consequence of Germany's economic, political, and military collapse at the end of the First World War.

"In the war, things were in terrible turmoil. What I had learned at the academy was of no use to me and the useful new ideas were still unready ... Everything had broken down and new things had to be made out of the fragments; and this is Merz. It was like a revolution within me, not as it was, but as it should have been."[7]

Der Sturm

Schwitters was to come into contact with Herwarth Walden after exhibiting expressionist paintings at the Hanover Secession in February 1918. He showed two Abstraktionen (semi-abstract expressionist landscapes) at Walden's gallery Der Sturm, in Berlin, in June 1918.[8] This resulted in meetings with members of the Berlin avant-garde, including Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch, and Jean Arp in the autumn of 1918.[2]

"[I remember] the night he introduced himself in the Café des Westens. "I'm a painter," he said, "and I nail my pictures together."

Whilst Schwitters still created work in an expressionist style into 1919 (and would continue to paint realist pictures up to his death in 1948), the first abstract collages, influenced in particular by recent works by Jean Arp, would appear in late 1918, which Schwitters dubbed Merz after a fragment of found text from the phrase Commerz Und Privatbank (commerce and private bank) in his work Das Merzbild, completed in the winter of 1918–19.[11][12] By the end of 1919 he had become a well-known artist, after his first one-man exhibition at Der Sturm gallery, in June 1919, and the publication, that August, of the poem An Anna Blume (translated as 'To Anna Flower', or 'To Eve Blossom'), a dadaist, non-sensical love poem. As Schwitters's first overtures to Zurich and Berlin Dada made explicit mention of Merz pictures,[13] there are no grounds for the widespread claim that he invented Merz because he was rejected by Berlin Dada.

Dada and Merz

Schwitters asked to join Berlin Dada either in late 1918 or early 1919, according to the memoirs of Raoul Hausmann.[14] Hausmann claimed that Richard Huelsenbeck rejected the application because of Schwitters's links to Der Sturm and to Expressionism in general, which were seen by the Dadaists as hopelessly romantic and obsessed with aesthetics.[15] Ridiculed by Huelsenbeck as 'the Caspar David Friedrich of the Dadaist Revolution',[16] he would reply with an absurdist short story, "Franz Mullers Drahtfrühling, Ersters Kapitel: Ursachen und Beginn der grossen glorreichen Revolution in Revon", published in the magazine Der Sturm (xiii/11, 1922), which featured an innocent bystander who started a revolution "merely by being there".[17]

Hausmann's anecdote about Schwitters asking to join Berlin Dada is, however, somewhat dubious, for there is well-documented evidence that Schwitters and Huelsenbeck were on amicable terms at first.[18] When they first met in 1919, Huelsenbeck was enthusiastic about Schwitters's work and promised his assistance, while Schwitters reciprocated by finding an outlet for Huelsenbeck's Dada publications. When Huelsenbeck visited him at the end of the year, Schwitters gave him a lithograph (which he kept all his life)[19] and though their friendship was by now strained, Huelsenbeck wrote him a conciliatory note. "You know I am well-disposed towards you. I think too that certain disagreements we have both noticed in our respective opinions should not be an impediment to our attack on the common enemy, the bourgeoisie and philistinism."[20] It was not until mid-1920 that the two men fell out, either because of the success of Schwitters's poem An Anna Blume (which Huelsenbeck considered unDadaistic) or because of quarrels about Schwitters's contribution to Dadaco, a projected Dada atlas edited by Huelsenbeck. It is unlikely that Schwitters ever considered joining Berlin Dada, however, for he was under contract to Der Sturm, which offered far better long-term opportunities than Dada's quarrelsome and erratic venture. If Schwitters contacted Dadaists at this time, it was generally because he was searching for opportunities to exhibit his work.

Though not a direct participant in Berlin Dada's activities, Schwitters employed Dadaist ideas in his work, used the word itself on the cover of An Anna Blume, and would later give Dada recitals throughout Europe on the subject with Theo van Doesburg, Tristan Tzara, Jean Arp and Raoul Hausmann. In many ways his work was more in tune with Zürich Dada's championing of performance and abstract art than Berlin Dada's agit-prop approach, and indeed examples of his work were published in the last Zürich Dada publication, Der Zeltweg,[21] November 1919, alongside the work of Arp and Sophie Taeuber. Whilst his work was far less political than key figures in Berlin Dada, such as George Grosz and John Heartfield, he would remain close friends with various members, including Hannah Höch and Raoul Hausmann, for the rest of his career.

In 1922 Theo van Doesburg organised a series of Dada performances in the Netherlands. Various members of Dada were invited to join, but declined. Eventually the programme comprised acts and performances by Theo van Doesburg, Nelly van Doesburg as Petrò Van Doesburg, Kurt Schwitters and sometimes Vilmos Huszàr. The Dada performances took place in various cities, amongst which Amsterdam, Leiden, Utrecht and The Hague. Schwitters also performed on solo evenings, one of which took place on 13 April 1923 in Drachten, Friesland. Schwitters later on visited Drachten quite frequently, staying with a local painter, Thijs Rinsema. Schwitters created several collages there, probably together with Thijs Rinsema. Their collages can sometimes hardly be distinguished from each other. From 1921 onwards there are signs of correspondence between Schwitters and an intarsia worker. From this co-operation several new works originated, where the collage technique was applied to woodwork, by incorporating several kinds of wood as a means to delineate images and letters. Thijs Rinsema also used this technique.[22]

Merz has been called 'Psychological Collage'. Most of the works attempt to make coherent aesthetic sense of the world around Schwitters, using fragments of found objects. These fragments often make witty allusions to current events. (Merzpicture 29a, Picture with Turning Wheel, 1920[23] for instance, combines a series of wheels that only turn clockwise, alluding to the general drift Rightwards across Germany after the Spartacist Uprising in January that year, whilst Mai 191(9),[24] alludes to the strikes organized by the Bavarian Workers' and Soldiers' Council.) Autobiographical elements also abound; test prints of graphic designs; bus tickets; ephemera given by friends. Later collages would feature proto-pop mass media images. (En Morn, 1947, for instance, has a print of a blonde young girl included, prefiguring the early work of Eduardo Paolozzi,[25] whilst many works seem to have directly influenced Robert Rauschenberg, who said after seeing an exhibition of Schwitters's work at the Sidney Janis Gallery, 1959, that "I felt like he made it all just for me.")[26]

Whilst these works were usually collages incorporating found objects, such as bus tickets, old wire and fragments of newsprint, Merz also included artists' periodicals, sculptures, sound poems and what would later be called "installations". Schwitters was to use the term Merz for the rest of the decade, but, as Isabel Schulz has noted, 'though the fundamental compositional principles of Merz remained the basis and centre of [Schwitters's] creative work [...] the term Merz disappears almost entirely from the titles of his work after 1931'.[27]

Internationalism, 1922–1937

Merz (periodical)

As the political climate in Germany became more liberal and stable, Schwitters's work became less influenced by Cubism and Expressionism. He started to organize and participate in lecture tours with other members of the international avant-garde, such as Jean Arp, Raoul Hausmann and Tristan Tzara, touring Czechoslovakia, the Netherlands, and Germany with provocative evening recitals and lectures.

Schwitters published a periodical, also titled Merz, between 1923 and 1932, in which each issue was devoted to a central theme. Merz 5 1923, for instance, was a portfolio of prints by Jean Arp, Merz 8/9, 1924, was edited and typeset by El Lissitzky, Merz 14/15, 1925, was a typographical children's story entitled The Scarecrow by Schwitters, Kätte Steinitz and Theo van Doesburg. The last edition, Merz 24, 1932, was a complete transcription of the final draft of the Ursonate, with typography by Jan Tschichold.[28]

His work in this period became increasingly Modernist in spirit, with far less overtly political context and a cleaner style, in keeping with contemporary work by Jean Arp and Piet Mondrian. His friendship around this time with El Lissitzky proved particularly influential, and Merz pictures in this period show the direct influence of Constructivism.

Thanks to Schwitters's lifelong patron and friend Katherine Dreier, his work was exhibited regularly in the US from 1920 onwards. In the late 1920s he became a well-known typographer; his best-known work was the catalogue for the Dammerstocksiedlung in Karlsruhe. After the demise of the Der Sturm gallery in 1924 he ran an advertising agency named Merzwerbe, which held the accounts for Pelikan inks and Bahlsen biscuits, amongst others, and became the official typographer for Hanover town council between 1929 and 1934.[29] Many of these designs, as well as test prints and proof sheets, were to crop up in contemporary Merz pictures.[30] In a manner similar to the typographic experimentation by Herbert Bayer at the Bauhaus, and Jan Tschichold's Die neue Typographie, Schwitters experimented with the creation of a new more phonetic alphabet in 1927. Some of his types were cast and used in his work.[31] In the late 1920s Schwitters joined the Deutscher Werkbund (German Work Federation).

The Merzbau

Alongside his collages, Schwitters also dramatically altered the interiors of a number of spaces throughout his life. The most famous was the Merzbau, the transformation of six (or possibly more) rooms of the family house in Hanover, Waldhausenstrasse 5. This took place very gradually; work started in about 1923, the first room was finished in 1933, and Schwitters subsequently extended the Merzbau to other areas of the house until he fled to Norway in early 1937. Most of the house was let to tenants, so that the final extent of the Merzbau was less than is normally assumed. On the evidence of Schwitters's correspondence, by 1937 it had spread to two rooms of his parents' apartment on the ground floor, the adjoining balcony, the space below the balcony, one or two rooms of the attic and possibly part of the cellar. In 1943 it was destroyed in an Allied bombing raid.

Early photos show the Merzbau with a grotto-like surface and various columns and sculptures, possibly referring to similar pieces by Dadaists, including the Great Plasto-Dio-Dada-Drama by Johannes Baader, shown at the first International Dada Fair, Berlin, 1920. Work by Hannah Höch, Raoul Hausmann and Sophie Taeuber, amongst others, were incorporated into the fabric of the installation. By 1933, it had been transformed into a sculptural environment, and three photos from this year show a series of angled surfaces aggressively protruding into a room painted largely in white, with a series of tableaux spread across the surfaces. In his essay 'Ich und meine Ziele' in Merz 21, Schwitters referred to the first column of his work as the Cathedral of Erotic Misery. There is no evidence that he used this title after 1930. The first use of the word 'Merzbau' occurs in 1933.[32]

Photos of the Merzbau were reproduced in the journal of the Paris-based group abstraction-création in 1933-34, and were exhibited in MoMA in New York in late 1936.

The Sprengel Museum in Hanover has a reconstruction of the first room of the Merzbau.[33]

Schwitters later created a similar environment in the garden of his house in Lysaker, near Oslo, known as the Haus am Bakken (the house on the slope). This was almost complete when Schwitters left Norway for the United Kingdom in 1940. It burnt down in 1951 and no photos survive. The last Merzbau, in Elterwater, Cumbria, England, remained incomplete on Schwitters's death in January 1948. A further environment that also served as a living space can still be seen on the island of Hjertøya near Molde, Norway. It is sometimes described as a fourth Merzbau, although Schwitters himself only ever referred to three. The interior has now been removed and will eventually be exhibited in the Romsdal Museum in Molde, Norway.[34]

Ursonate

Schwitters composed and performed an early example of sound poetry, Ursonate (1922–1932; a translation of the title is Original Sonata or Primeval Sonata). The poem was influenced by Raoul Hausmann's poem "fmsbw" which Schwitters heard recited by Hausmann in Prague, 1921.[35] Schwitters first performed the piece on 14 February 1925 at the home of Irmgard Kiepenheuer in Potsdam. He subsequently performed it regularly, both developing and extending it. He published his notations for the recital in the last Merz periodical in 1932, although he would continue to develop the piece for at least the next ten years.[36]

Exile, 1937–1948

Norway

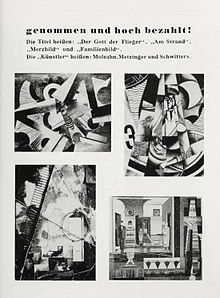

As the political situation in Germany under the Nazis continued to deteriorate throughout the 1930s, Schwitters's work began to be included in the Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) touring exhibition organised by the Nazi party from 1933. He lost his contract with Hanover City Council in 1934, and examples of his work in German museums were confiscated and publicly ridiculed in 1935. By the time his close friends Christof and Luise Spengemann and their son Walter were arrested by the Gestapo in August 1936[37] the situation had clearly become perilous.

On 2 January 1937 Schwitters, wanted for an "interview" with the Gestapo,[38] fled to Norway to join his son Ernst, who had already left Germany on 26 December 1936. His wife Helma decided to remain in Hanover, to manage their four properties.[37] In the same year, his Merz pictures were included in the Entartete Kunst exhibition in Munich, making his return impossible.

Helma visited Schwitters in Norway for a few months each year up to the outbreak of World War II. The joint celebrations for his mother Henriette's 80th birthday and his son Ernst's engagement, held in Oslo on 2 June 1939, would be the last time the two met.

Schwitters started a second Merzbau while in exile in Lysaker, near Oslo, in 1937, but abandoned it in 1940 when the Nazis invaded; this Merzbau was subsequently destroyed in a fire in 1951. His hut on the Norwegian island of Hjertøya, near Molde, is also frequently regarded as a Merzbau. For decades this building was more or less left to rot, but measures have now been taken to preserve the interior.[39]

The Isle of Man

Following Nazi Germany's invasion of Norway, Schwitters was amongst a number of German citizens who were interned by the Norwegian authorities at Vågan Folk High School in Kabelvåg on the Lofoten Islands,[40] Following his release, Schwitters fled to Leith in Scotland with his son and daughter-in-law on the Norwegian patrol vessel Fridtjof Nansen between 8 and 18 June 1940.

Officially an enemy alien, he was moved between various internment camps in Scotland and England before arriving on 17 July 1940 in Hutchinson Camp in the Isle of Man.[41][42] The camp was situated in a collection of terraced houses around Hutchinson Square in Douglas. The camp soon comprised some 1,205 internees by end of July 1940,[43] almost all of whom were German or Austrian. The camp was soon known as "the artists' camp", comprising as it did many artists, writers, university professors and other intellectuals.[44] In this environment Schwitters was popular as a character, a raconteur and as an artist.

He was soon provided studio space and took on students, many of whom would later become significant artists in their own right.[44] He produced over 200 works during his internment, including more portraits than at any other time in his career, many of which he charged for.[45] He contributed at least two portraits to the second art exhibition within the camp in November 1940, and in December he contributed (in English) to the camp newsletter, The Camp.

There was a shortage of art supplies there – at least during the early days of the camp's existence – which meant that the internees had to be resourceful to obtain the materials they needed: they would mix brick dust with sardine oil for paint, dig up clay for sculpture whilst out on walks, and rip up the linoleum floors to make cuttings which they then pressed through the clothes mangle to make linocut prints.[44] Schwitters's Merz extension of this included making sculptures in porridge:

"The room stank. A musty, sour, indescribable stink which came from three Dada sculptures which he had created from porridge, no plaster of Paris being available. The porridge had developed mildew and the statues were covered with greenish hair and bluish excrements of an unknown type of bacteria." Fred Uhlman in his memoir.[46]

Schwitters was well-liked in the camp, and was a welcome distraction from the internment they were suffering. Fellow internees would later recall fondly his curious habits of sleeping under his bed and barking like a dog, as well as his regular Dadaist readings and performances.[47][48] However, the epileptic condition which had not surfaced since his childhood began to recur whilst in the camp. His son attributed this to Schwitters's depression at being interned, which he kept hidden from others in the camp.

For the outside world he always tried to put up a good show, but in the quietness of the room I shared with him [...], his painful disillusion was clearly revealed to me. [...] Kurt Schwitters worked with more concentration than ever during internment to stave off bitterness and hopelessness.[49]

Schwitters applied as early as October 1940 for release (with the appeal written in English: "As artist, I can not be interned for a long time without danger for my art"),[50] but he was refused even after his fellow internees began to be released.

"I am now the last artist here – all the others are free. But all things are equal. If I stay here, then I have plenty to occupy myself. If I am released, then I will enjoy freedom. If I manage to leave for the U.S., then I will be over there. You carry your own joy with you wherever you go." Letter to Helma Schwitters, April 1941.[51]

Schwitters was finally released on 21 November 1941, with the help of an intervention from Alexander Dorner, Rhode Island School of Design.

London

After obtaining his freedom Schwitters moved to London, hoping to make good on the contacts that he had built up over his period of internment. He first moved to an attic flat at 3 St Stephen's Crescent, Paddington. It was here that he met his future companion, Edith Thomas:

“He knocked on her door to ask how the boiler worked, and that was that. [...] She was 27 – half his age. He called her Wantee, because she was always offering tea." Gretel Hinrichsen quoted in The Telegraph[52]

In London he made contact with and mixed with a range of artists, including Naum Gabo, László Moholy-Nagy and Ben Nicholson. He exhibited in a number of galleries in the city but with little success; at his first solo exhibition at The Modern Art Gallery in December 1944, forty works were displayed, priced between 15 and 40 guineas, but only one was bought.[53]

During his years in London, the shift in Schwitters's work continued towards an organic element that augmented the mass-produced ephemera of previous years with natural forms and muted colours. Pictures such as Small Merzpicture With Many Parts 1945–6,[54] for example, used objects found on a beach, including pebbles and smooth shards of porcelain.

In August 1942 he moved with his son to 39 Westmoreland Road, Barnes, London. In October 1943 he learnt that his Merzbau in Hanover had been destroyed in Allied bombing. In April 1944 he suffered his first stroke, at the age of 56, which left him temporarily paralyzed on one side of his body. His wife Helma died of cancer on 29 October 1944, although Schwitters only heard of her death in December.

The Lake District

Schwitters first visited the Lake District on holiday with Edith Thomas in September 1942. He moved there permanently on 26 June 1945, to 2 Gale Crescent Ambleside. However, after another stroke in February of the following year and further illness, he and Edith moved to a more easily accessible house at 4 Millans Park.

During his time in Ambleside Schwitters created a sequence of proto-pop art pictures, such as For Käte, 1947, after the encouragement from his friend, Käte Steinitz. Having emigrated to the United States in 1936, Steinitz sent Schwitters letters describing life in the emerging consumer society, and wrapped the letters in pages of comics to give a flavour of the new world, which she encouraged Schwitters to 'Merz'.[55]

In March 1947, Schwitters decided to recreate the Merzbau and found a suitable location in a barn at Cylinders Farm, Elterwater, which was owned by Harry Pierce, whose portrait Schwitters had been commissioned to paint. Having been forced by a lack of other income to paint portraits and popularist landscape pictures suitable for sale to the local residents and tourists, Schwitters received notification shortly before his 60th birthday that he had been awarded a £1,000 fellowship to be transferred to him via the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in order to enable him to repair or re-create his previous Merz constructions in Germany or Norway.[56] Instead he used it for the "Merzbarn" in Elterwater. Schwitters worked on the Merzbarn daily, travelling the five miles between his home and the barn, except for when illness kept him away. On 7 January 1948 he received the news that he had been granted British citizenship. The following day, on 8 January, Schwitters died from acute pulmonary edema and myocarditis, in Kendal Hospital.

He was buried on 10 January at St Mary's Church, Ambleside. His grave was unmarked until 1966 when a stone was erected with the inscription Kurt Schwitters – Creator of Merz. The stone remains as a memorial even though his body was disinterred and reburied in the Stadtfriedhof Engesohde in Hanover in 1970, the grave being marked with a marble copy of his 1929 sculpture Die Herbstzeitlose.

Gallery of works

- Schwitters, The Grave of Alves Bäsenstiel, 1919, drawing (narrator's name in his poem An Anna Blume)

- Schwitters, Merz-drawing 47, 1920, collage on board

- Schwitters, Merz-drawing 85, Zig-Zag Red, 1920, collage

- Schwitters, Merz 458 Wriedt, 1922, collage

- Poster for Dada Matinée, Jan. 1923, printed poster, announcing Kurt Schwitters, Theo van Doesburg & his wife Nelly

- Schwitters, Abstract Composition, 1923–25, oil-painting

- Schwitters, untitled (Agfa-Filmpack), c. 1925, collage

- Schwitters, untitled (Hamburg elevated train), 1929, collage on paper on board

- Schwitters, Merz 30, 42, 1930, collage

- Schwitters, untitled (Chessman), 1941, collage, oil, paper and wood on plywood

- Schwitters, untitled, early 1940s, collage

- Schwitters, Red wire sculpture, 1944, stone and metal

- Schwitters, Mother and Egg, 1945–47, mixed media sculpture

- Schwitters, Still life with wine bottle and fruit, c. 1948, oil on canvas

Posthumous reputation

Merzbarn

One entire wall of the Merzbarn was removed to the Hatton Gallery in Newcastle for safe keeping. The shell of the barn remains in Elterwater, near Ambleside.[57][58] [59] In 2011 the barn, but not the artwork inside it, was reconstructed in the front courtyard of the Royal Academy in London as part of its exhibition Modern British Sculpture.[60]

Influences

Many artists have cited Schwitters as a major influence, including Ed Ruscha,[61] Robert Rauschenberg,[62] Damien Hirst,[63] Al Hansen,[64] Anne Ryan, and Arman.[65]

"The language of Merz now finds common acceptance and today there is scarcely an artist working with materials other than paint who does not refer to Schwitters in some way. In his bold and wide-ranging experiments he can be seen as the grandfather of Pop Art, Happenings, Concept Art, Fluxus, multimedia art and post-modernism." Gwendolyn Webster[66]

Art market

Schwitters's Ja-Was?-Bild (1920), an abstract work made of oil, paper, cardboard, fabric, wood and nails, was sold £13.9 million at Christie's London in 2014.[67]

Marlborough Gallery controversy

Schwitters's son, Ernst, largely entrusted the artistic estate of his father to Gilbert Lloyd, director of the Marlborough Gallery. However, Ernst fell victim to a crippling stroke in 1995, moving control of the estate as a whole to Kurt's grandson, Bengt Schwitters. Controversy erupted when Bengt, who has said he has "no interest in art and his grandfather's works", terminated the standing agreement between the family and the Marlborough Gallery. The Marlborough Gallery filed suit against the Schwitters estate in 1996, after confirming Ernst Schwitters's desire to have Lloyd continue to administer the estate in his will.

Professor Henrick Hanstein, an auctioneer and art expert, provided key testimony in the case, stating that Schwitters was virtually forgotten after his death in exile in England in 1948, and that the Marlborough Gallery had been vital in ensuring the artist's place in art history. The verdict, which was eventually upheld by Norway's highest court, awarded the gallery USD 2.6 million in damages.[68]

Archival and forgeries

Schwitters's visual work has now been completely catalogued in the Catalogue Raisonné.[69] The Kurt Schwitters Archive at the Sprengel Museum in Hanover, Germany keeps a catalogue of forgeries.[70] A collage called "Bluebird" chosen for the cover of the catalogue for the Tate Gallery's 1985 Schwitters exhibition was withdrawn from the show after Ernst Schwitters told the gallery that it was a fake.[71]

Legacy

- Brian Eno sampled Schwitters's recording of Ursonate for the "Kurt's Rejoinder" track on his 1977 album, Before and after Science.[72]

- Electronic music duo Matmos used Ursonate in Schwitt/Urs on Quasi-Objects.[73]

- DJ Spooky included Anna Blume in a mix in his Sound Unbound project.[citation needed]

- Japanese musician Merzbow took his name from Schwitters.[74]

- A fictionalised account of Schwitters's encounter with a boy in London and their dispute over a bus ticket is the subject of Man and Boy: Dada, an opera by Michael Nyman and Michael Hastings.[75]

- The German hip-hop band Freundeskreis quoted from his poem An Anna Blume in their hit single "ANNA".[76]

- The krautrock band Faust have a song entitled "Dr. Schwitters snippet".[77]

- Billy Childish made a short film on Schwitters' life, titled The Man with Wheels (1980, directed by Eugean Doyan).[78]

- Chumbawamba include extracts from Ursonate in their song "Ratatatay". The song references George Melly's anecdote about spontaneously reciting Ursonate, in order to scare off a pair of robbers.[79]

- Einstürzende Neubauten include samples of member N. U. Unruh reciting Ursonate in the song "Let's Do It A Dada" on the album Alles wieder offen.[citation needed]

- Contemporary artists Jutta Koether, Carl Michael von Hausswolff, Kenneth Goldsmith, Eline McGeorge and Karl Holmqvist were commissioned to make new installation works in 2009 in response to Kurt Schwitters as part of the Senses[80] exhibition which took place in Ålesund, Norway (2009) and at Chisenhale Gallery, London (2010).

- Three members of the band British Sea Power were brought up near Schwitters's home in Cumbria. They have referenced his work in their songs and used a recording of Ursonate at their live shows. Jan Scott Wilkinson of the band contributed to Tate Britain's Schwitters retrospective in 2013.[81]

- Tonio K dedicated the track "Merzsuite – Let Us Join Together in a Tune, Umore, Futt Futt Futt" on his album Amerika to Kurt Schwitters.[82]

- American author Paul Auster uses the name Anna Blume repeatedly in his works. For example, the main character in In the Country of Last Things is named Anna Blume.[83]

- Ed Ackerman and Colin Morton's 1986 stop-action animation Primiti Too Taa has a soundtrack of part of "Ursonate" and visuals are spellings of the sounds done by an unseen typewriter.[84]

- The multi-channel sound work Urbirds singing the Sonata by the artist Astrid Seme narrates what Kurt Schwitters might have heard when he wrote the Ursonate and its rhythmic score.[85]

Notes

- ^ "Sprengel Museum, Hanover" (PDF). Retrieved 17 February 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Schröder, Silke; Husslik, Jürgen; Gottfried, Sagitta. "Kurt & Ernst Schwitters Archive". Schwitters-stiftung.de. Hanover: Schlütersche Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG. Archived from the original on 23 May 2008. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ Walter Selke, Christian Heppner: The birthplace of Kurt Schwitters in Hanover, in: Hannoversche Geschichtsblätter, vol. 70 (2016), p. 66–71

- ^ Plaque at birthplace, erected by the City of Hanover in 2021

- ^ Dada, Leah Dickerman, National Gallery of Art, Washington p. 158

- ^ Quoted in The Collages of Kurt Schwitters, Dietrich, Cambridge University Press 1993, p. 86

- ^ The Collages of Kurt Schwitters, Dietrich, Cambridge University Press 1993, pp. 6–7

- ^ Dada, Leah Dickerman, National Gallery of Art, Washington p. 432

- ^ "Kurt Schwitters (Biografie)". Dieterwunderlich.de. Archived from the original on 23 October 2009. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ "Colin Morton: The Merzbook: Kurt Schwitters Poems". Capa.conncoll.edu. 7 November 1918. Archived from the original on 19 October 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ Kurt Schwitters, Center Georges Pompidou, 1994, p. 47

- ^ The Merzbild can be seen in the centre of the Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition, 1937, directly below the phrase 'Nehmen Sie Dada Ernst', and was presumably destroyed by the Nazis shortly afterward.

- ^ Raoul Schrott, dada 15/25, Haymon Verlag, Innsbruck 1992, pp. 225, 229

- ^ Raoul Hausmann, Am Anfang war Dada, 3rd edition, ed. Karl Riha and Günter Kämpf (Giessen, 1992), p. 63.

- ^ [1] Archived 29 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine note 23

- ^ quoted in The Grove Dictionary of Art, Oxford University Press, 1996, Essay on Kurt Schwittters by Richard Humphreys

- ^ "The Collection | Kurt Schwitters. (German, 1887–1948)". MoMA. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ Ralf Burmeister, 'Related Opposites. Differences in Mentality between Dada and Merz', in Kurt Schwitters: Merz – a Total Vision of the World, exhibition catalogue, Museum Tinguely, Basel 2004, 140–49.

- ^ Karin Orchard & Isabel Schulz (ed.) Kurt Schwitters Catalogue Raisonné 1905–22, Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern, 2000, no. 575

- ^ Ralf Burmeister, 'Related Opposites. Differences in Mentality between Dada and Merz', in Kurt Schwitters: Merz – a Total Vision of the World, exhibition catalogue, Museum Tinguely, Basel 2004, p. 144.

- ^ Dada, Leah Dickerman, National Gallery of Art Washington, p. 167

- ^ Thijs/Evert Rinsema: Eigenzinnig en Veelzijdig, Thijs Rinsema, Drachten, 2011

- ^ In the Beginning Was Merz, Mayer-Buser, Orchard, Hatje Cantz, p. 55

- ^ The Collages of Kurt Schwitters, Dietrich, Cambridge, 1993, p. 111

- ^ In The Beginning Was Merz, Meyer-Buser, Orchard, Hatje Cantz, p. 186

- ^ Quoted in Rauschenberg/Art and Life, Mary Lynn Kotz, Harry N Abrams, p. 91

- ^ Isabel Schulz, 'What Would Life be Without Merz? On the Evolution and Meaning of Kurt Schwitters' Concept of Art', in the Beginning was Merz – From Kurt Schwitters to the Present Day, exhibition catalogue, Sprengel Museum Hannover, Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern, 2000. p. 249.

- ^ For a more detailed overview of the Merz journals, see Roger Cardinal and Gwendolen Webster, Kurt Schwitters, Hatje Cantz 2011, pp. 132–135.

- ^ "Oxford Art Online, Subscription Only". Archived from the original on 10 May 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ See Roger Cardinal and Gwendolen Webster, Kurt Schwitters, Hatje Cantz 2011, p 136-9.

- ^ A digital revival of Schwitters's 1927 Systemschrift typeface called Architype Schwitters was released in 1997.

- ^ Letter from Helma Schwitters to Hannah Höch, 5 April 1933, in Ralf Burmeister und Eckhard Fürlus (ed.) Hannah Höch, Eine Lebenscollage, Part II, vol. 2, Berlinische Galerie, Berlin 1995, p. 482.

- ^ Kurt Schwitters Merzbau in Hanover 1933 Archived 23 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ See the Kurt Schwitters project at the Heine Onstad art centre] in Høvikodden, Norway. "THE KURT SCHWITTERS ROOM - Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter". Archived from the original on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ "UbuWeb; Sound". Ubu.com. 5 May 1932. Archived from the original on 15 December 2003. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 February 2006. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b Schröder, Silke; Husslik, Jürgen; Gottfried, Sagitta. "Kurt & Ernst Schwitters Archive". Schwitters-stiftung.de. Hanover: Schlütersche Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG. Archived from the original on 23 May 2008. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ "Stunned Art". Stunned.org. 26 December 1936. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ See the Kurt Schwitters Project at Henie Ostad art centre in Norway."THE KURT SCHWITTERS ROOM – Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter". Archived from the original on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ For a comprehensive account of this period, see Webster, Gwendolen, "Kurt Schwitters on the Lofoten islands", Kurt Schwitters Society Journal, 2011, p. 40–49, ISSN 2047-1971

- ^ Cooke, Rachel (6 January 2013). "Kurt Schwitters: the modernist master in exile". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ "Kurt Schwitters". Kurt and Ernst Schwitters Foundation. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ Island of Barbed Wire, Connery Chappel, Corgi Books, London, 1986, p. 53

- ^ a b c The Forced Journeys: Artists in Exile in Britain, c. 1933–45 Archived 15 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Sarah MacDougall and Rachel Dickson, Manx National Heritage lecture delivered 10 April 2010

- ^ "Schwitters in Britain: Exhibition guide: Room 2". Tate. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ Quoted in "Pop Art pioneer is back in the picture" Archived 11 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, by Arifa Akbar in The Independent, 27 January 2013

- ^ Obituary of Klaus Hinrichsen Archived 5 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 28 September 2004

- ^ Freddy Godshaw recollections of Hutchinson Camp on the Archived 23 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine BBC

- ^ Ernst Schwitters's letter in Art and News Review, Saturday 25 October 1958, Vol X, No. 20, p. 8

- ^ Schwitters in Britain Tate Britain exhibition exhibits, 30 January – 12 May 2013

- ^ quoted in Kurt Schwitters, Centre Georges Pompidou, 1995, p. 310

- ^ Kurt Schwitters, inspiration of pop art Archived 5 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine by Mark Hudson in The Daily Telegraph, 27 January 2013

- ^ Art Sales: Kurt Schwitters' Material World Archived 5 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine by Colin Gleadell, in The Telegraph, 22 January 2013

- ^ In The Beginning Was Merz, Meyer-Buser, Orchard, Hatje Kantz, p. 163

- ^ In The Beginning Was Merz, Meyer-Buser, Orchard, Hatje Kantz, p. 292

- ^ See Adrian Sudhalter,Kurt Schwitters and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, 2007 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Philip Oltermann (28 April 2009). "Kurt Schwitters, the great dadaist of Cumbria | Art and design". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ "Merzbarn". Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ The site has now been purchased from its former owners and will house a digital replica of the wall in Newcastle, and, eventually, a Kurt Schwitters study centre.

- ^ "Learn More: The Merz Barn by Kurt Schwitters". The Royal Academy. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Arquivo.pt". arquivo.pt. Archived from the original on 28 June 2009. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ "Exhibition at the Centre Pompidou". Centrepompidou.fr. Archived from the original on 12 February 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ "Tate Online; See under The Artist>biography". Tate.org.uk. Archived from the original on 22 June 2008. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ "Catalogue by claudia zanfi, exhibition Milan 2003". Designboom.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ "Grove Online Dictionary of Art, available subscription only". Archived from the original on 10 May 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ "Artchive Online". Artchive.com. 8 January 1948. Archived from the original on 28 May 2005. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ Georgina Adam (27 June 2014), Record set for Schwitters in Christie’s sale Archived 16 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine Financial Times.

- ^ Alexander, Leslie. "Marlborough Vindicated". Art & Antiques April 2001: 38.

- ^ "Hatje Cantz Verlag | Suche: kurt schwitters". Hatjecantz.de. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ Duffin, Claire; Mendick, Robert (8 February 2014). "Old master of the faked paintings that sell for £250". telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ "Collage Called Fake, Withdrawn from Tate Exhibit". apnews.com. AP. 11 November 1985. Archived from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ Christopher Scoates (24 September 2013). Brian Eno: Visual Music. Chronicle Books. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-4521-2948-8.

- ^ "Adam de la Cour & Neil Luck Perform Kurt Schwitters "Ursonate"". The Wire. May 2019. Archived from the original on 12 October 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- ^ Frere-Jones, Sasha (26 June 2012). "Merzbiebs: Things You Think You Don't Want to Hear". The New Yorker. Conde Naste. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ bwitherden. "Nyman Man and Boy: Dada". gramophone.co.uk. Mark Allen Group. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Seifert, Anja (29 April 2004). Körper, Maschine, Tod.: Zur symbolischen Artikulation in Kunst und Jugendkultur des 20. Jahrhunderts [Body, machine, death: On the symbolic articulation in art and youth culture of the 20th century] (in German). Springer-Verlag. p. 137. ISBN 978-3-8100-4164-7.

- ^ "Faust – Dr. Schwitters (Snippet) – YouTube". www.youtube.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ Brown, Neal (2008). Billy Childish: A Short Study. [London]: The Aquarium. ISBN 978-1-871894-23-3

- ^ Richard Elliott (28 December 2017). The Sound of Nonsense. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-5013-2456-7.

- ^ "Electra". Electra-productions.com. 27 June 2009. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ British Sea Power's Yan on Kurt Schwitters Archived 20 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine Tate.org.uk, 26 March 2013

- ^ Krikorian, Mark (24 April 2012). "Tonio K – 10 – Merzsuite – Let Us Join Together in a Tune, Umore, Fut Fut Fut – Amerika (1980)". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ Beyerle, Stefan (11 September 2017). ""Many of those who sleep in the land of dust shall awake!" (Dan 12:2) - Towards a matrix of Apocalyptic Eschatology in Ancient Judaism". In Chalamet, Christophe; Dettwiler, Andreas; Mazzocco, Mariel; Waterlot, Ghislain (eds.). Game Over?: Reconsidering Eschatology. De Gruyter. p. 3. ISBN 978-3-11-052141-2.

- ^ Noel Taylor, "Ottawa poet up for Genie; Animated movie a David against two NFB Goliaths". Ottawa Citizen, March 22, 1989.

- ^ "IMA". ima.or.at. Archived from the original on 28 July 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

References

- Burns Gamard, Elizabeth. Kurt Schwitters' Merzbau: The Cathedral of Erotic Misery, Princeton Architectural Press, 2000, ISBN 1-56898-136-8

- Cardinal, Roger, and Webster, Gwendolen. Kurt Schwitters, Hatje Cantz, Stuttgart, 2011 (versions in English and in German)

- Crossley, Barbara. The Triumph of Kurt Schwitters, Armitt Trust Ambleside, 2005

- Elderfield, John. Kurt Schwitters, Thames and Hudson, London, 1985

- Elsner, John, and Cardinal, Roger (eds.) The Cultures of Collecting, Reaktion Books, London, 1994

- Feaver, William. "Alien at Ambleside", The Sunday Times Magazine, 18 August 1974, 27–34

- Fiske, Lars, and Kverneland, Steffen. Kanon (3 volumes) – a Norwegian comic biography

- Germundson, Curt. "Montage and Totality: Kurt Schwitters' relationship to tradition and avant-garde", in Jones, Dafydd (ed.), Dada Culture: Critical Texts on the Avant-Garde, Rodopi, Amsterdam/New York 2006, 156–186

- Hausmann, Raoul and Schwitters, Kurt; Reichardt, Jasia, ed. PIN, Gaberbocchus Press (1962); Anabas-Verlag, Giessen (1986)

- Luke, Megan R., Kurt Schwitters: Space, Image, Exile, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013, ISBN 9780226085180

- McBride, Patrizia C. "The Game of Meaning: Collage, Montage, And Parody In Kurt Schwitters' Merz". Modernism/Modernity 14.2 (2007): 249–272

- McBride, Patrizia. "Montage And Violence In Weimar Culture: Kurt Schwitters' Reassembled Individuals". Contemplating Violence: Critical Studies in Modern German Culture. 245–265. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Rodopi, 2011

- Notz, Adrian and Obrist, Hans Ulrich (ed.), 'Processing the Complicated Order. The Merzbau Today'. Archived 19 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine With contributions by Peter Bissegger, Stefano Boeri, Dietmar Elger, Yona Friedman, Thomas Hirschhorn, Karin Orchard, Gwendolen Webster.

- Ramade, Bénédicte. (2005) Dada: L'exposition/The Exhibition, Union-Distribution, ISBN 2-84426-278-3

- Rothenberg, Jerome, and Joris, Pierre (eds.) Kurt Schwitters, poems, performance, pieces, proses, play poetics, Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 1993

- Schwitters, Kurt (ed.) Merz 1923–32. Hanover, 1923–1932 [numbered 1–24; nos. 10, 22–23 never published: see also the University of Iowa Dada archive Archived 5 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- Themerson, Stefan. Kurt Schwitters in England 1940–1948, Gaberbocchus Press (1958) [includes poems and writings by Schwitters]

- Themerson, Stefan. "Kurt Schwitters on a Time-Chart" in Typographica 16, December 1967, 29–48

- Uhlman, Fred. The Making of an Englishman, Gollancz (1960)

- Webster, Gwendolen. 'Kurt Schwitters' Merzbau' Archived 9 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine doctoral dissertation, Open University, 2007

- Webster, Gwendolen. Kurt Merz Schwitters, a Biographical Study, University of Wales Press, 1997, ISBN 0-7083-1438-4

- Webster, Gwendolen. Kurt Schwitters and Katherine Dreier Archived 29 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine in German Life and Letters 1999, vol. 52, no. 4, 443–456

- Exhibition catalogue, In the Beginning was Merz – From Kurt Schwitters to the Present Day, Sprengel Museum Hanover, Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern, 2000

- Exhibition catalogue, Kurt Schwitters in Exile: The late work, 1937–1948, Marlborough Fine Art, 1981

- Exhibition catalogue, Kurt Schwitters, Galerie Gmurzynska, 1978

- "Kurt Schwitters: Portrait of a starving artist". BBC News. 29 January 2013. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- "Adam de la Cour & Neil Luck Perform Kurt Schwitters "Ursonate"". The Wire. May 2019. Archived from the original on 12 October 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

Further reading

- Bader, Graham (2021). Poisoned Abstraction: Kurt Schwitters Between Revolution and Exile. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-25708-3. Archived from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- Schwitters, Kurt (10 March 2021). Myself and My Aims: Writings on Art and Criticism. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-12939-6.

- Review of both books: Foster, Hal (10 March 2022). "Anyone can do collage". London Review of Books. 44 (5). Archived from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

External links

- Gallery of his works, with information on each (German)

- Kurt Schwitters Archive, Sprengel Museum, Hanover (information about Schwitters and his work, at present only in German)

- Kurt Schwitters Society UK

- Scans of Schwitters's publication Merz Archived 5 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- Works from the Guggenheim Collection

- Cut & Paste: A History of Photomontage

- Information on copyright from the Kurt Schwitters Foundation Archived 18 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Schwitters@Newcastle" a project run by the German Studies Section at the School of Modern Languages at Newcastle University

- Kurt Schwitters at Library of Congress, with 75 library catalogue records

- Kurt Schwitters at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database