Medal of John VIII Palaeologus

| Medal of John VIII Palaeologus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Pisanello |

| Year | 1438 |

| Type | cast bronze, and other metals |

| Dimensions | 10.3 cm (4.1 in) |

The medal of John VIII Palaeologus is a portrait medal by the Italian Renaissance artist Pisanello. It is generally considered to be the first portrait medal of the Renaissance.[1][2][3] On the obverse of the medal is a profile portrait of the penultimate Byzantine emperor, John VIII Palaeologus; the reverse contains an image of the emperor on horseback before a wayside cross. Although the date of the work is not clear it was likely to have been some time during 1438 and 1439, the years John was in Italy attending the Council of Ferrara (later moved to Florence). It is not known whether the emperor himself or his Italian hosts commissioned Pisanello to make the medal, but Leonello d’Este, the heir apparent to the marquisate of Ferrara, has been suggested as the most likely candidate.[4] Several drawings by Pisanello are closely associated with the medal and these include sketches now held in Paris and Chicago.

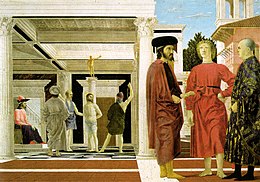

Its impact on art was significant: it extended beyond numismatics and the proliferation of outstanding Renaissance medals to influence sculpture and painting. Renaissance artists subsequently used Pisanello's portrait of John almost as a stock type to represent exotic or antique figures.[5] This can be seen in the work of Piero della Francesca who used the image of John in his Flagellation of Christ and Arezzo frescoes.[6]

Description

A number of specimens exist of Pisanello's medal of John; most of these are bronze or lead casts. Renaissance medals were often produced in a variety of metals, sometimes with a few gold or silver ones. The bronze example in the British Museum measures 10.3 centimetres in diameter.[7] The obverse of the work portrays a bust of the emperor looking to the right. His hair hangs in corkscrew curls and he sports a moustache and pointed beard. The emperor's back is curved, giving the suggestion of a slight stoop. He is dressed in a high-necked shirt with an open jacket, with discernible buttons on both garments. The most striking aspect of the portrait is the emperor's hat: this large garment occupies around half the pictorial space of the obverse. The hat is sharply peaked and its crown is tall, domed and vertically ribbed. Extravagant hats were typical of Byzantine officialdom and many were drawn by Pisanello. At the summit of the hat is a jewel which intrudes into the space of the Greek inscription encircling the portrait. The inscription reads: +ἸΩÁΝΝΗC • BACIΛEV̀C • KAÌ • ἈVTOKPÁTΩP • ῬΩMÁIΩN • Ὁ • ΠAΛΑIOΛÓΓΟC (‘John, emperor and autocrat of the Romans, the Palaeologus’).[8] This style of hat is similar to that which had often been used to represent Mongols in earlier European painting.

Unlike some of Pisanello's other portrait medals, such as those of Leonello d'Este,[9] the reverse of the medal of John presents no iconographic or allegorical mysteries. It shows the emperor on horseback, in profile to the right. Behind him, mounted on another horse, is a page or squire viewed from the rear and foreshortened. The emperor wears his distinctive hat and carries a bow on his left side and a quiver of arrows above his right leg. The double reins of the emperor's horse are visible and both horses possess elaborate straps over their hindquarters. The illustration conveys the arrest of a hunting expedition occasioned by John's encounter with a pedestalled wayside cross. The gesture of the emperor's raised right hand indicates his acknowledgement, in an act of piety, of the cross before him. The event takes place in a rocky landscape and is framed in the bottom portion by a Greek inscription: ἜPΓON • TÔV • ΠICÁNOV • ZΩΓPÁΦOV (‘The work of Pisano the painter’). This inscription is repeated in Latin within the top of the scene: OPVS • PISANI • PICTORIS.[10]

Historical context

The Council of Ferrara

Pisanello's medal was created in response to John's visit to Italy. The emperor had been invited to attend the council in Ferrara by pope Eugenius IV to address the question of unifying the Latin and Greek churches. One of John's chief motivations for unification was to secure help from the western powers in order to meet the constant threat to his crumbling empire from the Turks.[11] The emperor arrived in Venice in February 1438 where he was met by Niccolò III d'Este, Marquis of Ferrara. Niccolò, with his sons Leonello and Borso, accompanied the emperor as they rode into Ferrara on the 4 March. Following its first magnificent opening public session on 9 April 1438, the council was repeatedly postponed until the 8 October to allow the many different representatives of the European rulers to arrive.

During this lengthy period of waiting for the representatives, the emperor relocated outside of Ferrara because of an outbreak of plague in the city.[12] He occupied himself with hunting: his enthusiasm for the sport was such that Niccolò was forced on two occasions to make unsuccessful representations to the emperor requesting that he restrain his hunting activities because of the damage to the local game population and surrounding properties.[13] John was also criticized by the contemporary Greek chronicler Syropoulos (who was possibly Patriarch Sophronius I of Constantinople when a young cleric) for spending "all his time hunting without bothering in the slightest with ecclesiastical affairs."[14]

In order to encourage John's attendance to the council, the pope offered to pay the expenses of the Greek delegation. Eugenius found this offer extremely difficult to honour, particularly as John's entourage numbered around seven hundred. In January 1439, however, the Council removed to Florence upon the invitation of Cosimo de' Medici to whom the pope was heavily indebted. In Florence contentious points of theology were resolved, particularly the Filioque, which had contributed significantly to the Great Schism.[15] A decree of union was signed in Florence in July 1439. When John and his delegation returned to Constantinople, however, it was strongly rejected by the clergy and lay population there, and never took effect.

Although the exact date of Pisanello's medal is not known, most writers hold that it is more likely to have been made in Ferrara rather than Florence. One reason for this is the existence of a letter dated 12 May 1439 in which Pisanello is promised payment from a church in Mantua, near Ferrara.[16]

Drawings

Some notable drawings and sketches are associated with Pisanello's medal. One is a highly finished pen drawing of a saddled and harnessed horse from the front and the back (The Louvre, Vallardi, 2468, fol. 277). The horse from the back is clearly the same horse as that of the emperor's squire on the reverse of the medal. The horse is very likely to have come from a Byzantine stable because of its slit nostrils. It was believed in some oriental countries that slitting the nostrils of horses enabled them to breathe easier under exertion.[17] A similarly maltreated horse is depicted in the centre of the Paris sheet of sketches of John and members of his retinue.

The sketches of John on sheets held in Paris and Chicago are the only drawings by Pisanello that can be securely dated and provide firm evidence of his presence in Ferrara.[18] The figure on the horse in the recto of the Paris leaf (Louvre MI 1062) is undoubtedly the emperor because of the Italian inscription above the figure, part of which reads: "The hat of the Emperor should be white on top and red underneath, the profile black all around. The doublet of green damask, and the mantle of top crimson. A black beard on a pale face, hair and eye-brows alike."[19] Pisanello's references to colours on this sheet suggests that the artist intended to do a painting of the emperor.[20]

Scholars differ as to the circumstances of the production of the Paris and Chicago sheets and what they depict. It has been argued that Pisanello made his drawings at the opening of the first dogmatic session on 8 October 1438 when the emperor, in a characteristic insistence on punctilio, required that he be allowed to proceed on horseback to his throne in the council chamber.[21] While the emperor and his retinue waited outside for this impossible demand to be accommodated, Pisanello had the opportunity to sketch the emperor and members of his delegation, including perhaps Joseph II. Contrary to this position, however, is the argument that every figure (except the standing figure in the centre of the Chicago recto) is a drawing of the emperor. This view argues that the Paris and Chicago leaves show Pisanello's early attempt to formulate the composition of the medal by sketching the emperor in diverse poses wearing different hats and robes.[22]

Influences on the creation of Pisanello's medal

Humanism and Ancient Rome

It is probable that Pisanello's portrait medals were cast with the intention of reviving the form of ancient coins. Pisanello's medal of John can be firmly located within a period when the court at Ferrara was witnessing an escalation in the appreciation of classical learning. Niccolò III d’Este was the first lord of Ferrara to be educated by a Renaissance humanist and in 1429 he invited the humanist scholar, Guarino da Verona, to tutor his son Leonello. Leonello cultivated a strong admiration for writers like Cicero. During his reign in the 1440s he resolved to revitalise the Studium of Ferrara by recruiting more humanist scholars to work there.[23] Part of this appreciation gave rise to the study of ancient coins: these were the most enduring and abundant artefacts available from antiquity and Leonello himself was an enthusiastic numismatist. Pisanello's own personal interest in Roman coins is vividly apparent from his drawings of them, and his successful development of the portrait medal as a medium of sculpture can be explained in part to its similarity to coins. The medal evoked a powerful link to antiquity which made it very appealing to patrons.[24]

It has been suggested that Leon Battista Alberti may have played a significant role in Pisanello's conception of the medal of John.[25] Alberti attended the Council in Ferrara as a member of the papal Curia and could therefore have encountered Pisanello. Between 1430 and 1435, Alberti cast a bronze, self-portrait plaque in a style that was clearly influenced by Roman imperial portraits. Alberti's plaque was the first labeled self-portrait of an artist.[26]

Franco-Burgundian culture

In Northern Italian city-states like Ferrara, the literary culture of high society in the early fifteenth century was more French than Italian,[27] hence there was a strong culture of chivalry in these areas. Pisanello's medal reflects this culture in its portrayal of John as a huntsman. Hunting was regarded as a noble activity in Italy and was a central ingredient in medieval Romance literature. Franco-Burgundian art in particular celebrated the hunt and certain images of animals by Pisanello are thought to have derived from miniatures from the canonical version of the Livre de Chasse by Gaston Phoebus.[28]

The reverse of the medal is similar in many respects to Pisanello's Vision of St Eustace. This painting also presents a huntsman on horseback arrested by the sight of a cross and it contains animals that seem to have derived from illuminations in French hunting treatises.[29]

The similarity between John and St Eustace in Pisanello's respective representations could signify the artist's attempt to present John as a modern St Eustace.[30]

Constantine and Heraclius medals

Two important prototypes for Pisanello's portrait medal were copies of the medals of the emperors Constantine and Heraclius. It is believed that Jean, duke of Berry commissioned the medals to be copied from originals, now lost, during the period 1402–1413. The original Constantine medal was purchased by the duke from a Florentine merchant in 1402, which closely associates the medals with the visit of John's father, Manuel II Palaeologus, to Paris from 1400 to 1402. The Heraclius medal was likely to have been acquired at the same time. Jean's acquisition of the medals could have been intended as gifts for the Byzantine emperor in response to a group of relics Jean received from Manuel. The political context in which Jean de Berry's medals were purchased was therefore similar to that in which Pisanello cast his medal of John: Manuel II, like his son after him, also visited the west in an attempt to secure protection for Constantinople from the Ottomans. The context of their purchase and the lack of any numismatic precedent for the medals suggests the originals may well have had Byzantine enkolpia as their model: these were sacred objects "worn about the neck and endowed with spiritual efficacy’.[31]

The Constantine and Heraclius medals were widely circulated in Italy and the Heraclius medal was recorded in an inventory of Niccolò d’Este's treasures in 1432. Pisanello's familiarity with both medals seems unquestionable because of their similarity in size and design to the medal of John VIII. Pisanello appears to have merged various elements from both medals to produce a single piece. The obverse of the Constantine medal, for example, is an equestrian portrait, and that of the Heraclius medal is a profile portrait. Like Pisanello's medal, the obverse of the Heraclius medal shows the emperor with a servant and contains text in both Greek and Latin. Both emperors were associated with the True Cross, which is portrayed on their obverses. The ownership of the True Cross relic was something of which the Palaeologus dynasty was very proud, making these highly appropriate models for Pisanello to use. It is not known whether Pisanello believed the medals to have come from antiquity or if he was aware of their more recent French background. It is certainly plausible that he observed their similarity of style with that of French illuminated manuscripts and therefore hoped to harness, through his medal, their associations with the culture of chivalry rather than antiquity.[32] The bold yet refined technique and style of Pisanello's medal is nevertheless clearly different from that of the more overtly intricate Constantine and Heraclius medals.[33]

Impact on art

The success of Pisanello's medal is evident from the flow of commissions that the artist received from patrons including Filippo Maria Visconti and Francesco Sforza. It initiated the creation of a new art form in which Pisanello set the highest standards that later medallists found hard to equal.[34]

The success of the medal is also clear from the number of Renaissance sculptors, illuminators and painters who used Pisanello's portrait of John almost as a stock type for figures from distant lands or times. Piero della Francesca is perhaps the most celebrated artist in this respect. In his fresco of Constantine leading his troops into battle by the Milvian Bridge in The History of the True Cross series of frescos in Arezzo, the portrait and headgear of Constantine is clearly modeled on Pisanello's medal.[35] Piero also used Pisanello's portrait of John to depict Pontius Pilate in his Flagellation of Christ.[36]

Other notable artists who were either directly or indirectly acquainted with Pisanello's image of John include Filarete, whose bronze doors for St. Peter's Church in Rome from 1445 depicts the journey home of John from the Council of Florence, and Gozzoli who used John's image as a model to depict one of the magi in his Magi Chapel. John's profile can also be clearly discerned in Carpaccio's St Stephen is Consecrated Deacon from 1511.[37]

Notes

- ^ Scher, p.45

- ^ Weiss, p.10

- ^ Jardine and Brotton, p.25

- ^ Scher, p.46

- ^ Weiss, p.28

- ^ Weiss, p.23

- ^ Cast bronze medal of John VIII Palaeologus, Emperor of Byzantium, by Pisanello - British Museum website

- ^ Jardine and Brotton, p.26

- ^ Gordon and Syson, pp.90-91

- ^ Jardine and Brotton, p.26

- ^ Scher, p.46

- ^ Gordon and Syson, p.31

- ^ Gill, p.114

- ^ Jardine and Brotton, p.28

- ^ Gordon and Syson, p.31

- ^ Jones (1979), p.14

- ^ Hill (1964), p.34

- ^ Gordon and Syson, p.34

- ^ Fasanelli, p.38

- ^ Gordon and Syson, p.34

- ^ Fasanelli, 1965, p.39

- ^ Vickers, p.424

- ^ Gundersheimer, p.100

- ^ Gordon and Syson, p.95

- ^ Scher, p.46

- ^ Scher, p.41

- ^ Woods-Marsden, p.402

- ^ Gordon and Syson, p.85

- ^ Gordon and Syson, p.167

- ^ Gordon and Syson, p.114

- ^ Jones, 2010, p.6

- ^ Gordon and Syson, p.114

- ^ Jones (1979), p.16

- ^ Jones (1979), p.27

- ^ Weiss, p.23

- ^ Gordon and Syson, p.195

- ^ Weiss, p.23

References

- Fasanelli, J. A., (1965) ‘Some Notes on Pisanello and the Council of Florence’, Master Drawings, vol.3, no.1 pp. 36–47

- Gill, J. (1964) Personalities of the Council of Florence, and other essays. Oxford, Basil Blackwell.

- Gordon, D., Syson, L. (2001) Pisanello: Painter to the Renaissance Court, London, National Gallery.

- Gundersheimer, W. L. (1973) Ferrara; the Style of a Renaissance Despotism, Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press.

- Hill, G. F. (1965) Drawings by Pisanello, New York, Dover.

- Hill, G. F., (1905) Pisanello, London, Duckworth & Co.

- Jardine, L., Brotton, J. (2000) Global Interests : Renaissance Art Between East and West, London, Reaktion.

- Jones, M. (1979) The Art of the Medal, British Museum, London

- Jones, T. L. (2010) ‘The Constantine and Heraclius Medallions: Pendants Between East and West’, The Medal, no.56, pp. 5–13

- Phébus, G. (1998) The hunting book of Gaston Phébus : manuscrit francais 616, Paris, Bibliotheque nationale, intro. Marcel Thomas and Francois Avril, London, Harvey Miller

- Scher, S. K. (1994) The Currency of Fame: Portrait Medals of the Renaissance, London, Thames and Hudson.

- Vickers, M. (1978) ‘Some Preparatory Drawings for Pisanello's Medallion of John VIII Palaeologus’, The Art Bulletin, vol. 60, no.3, pp. 417–424.

- Weiss, R. (1966) Pisanello's Medallion of the emperor John VIII Palaeologus, British Museum, Oxford.

- Woods-Marsden, J. (1985) ‘French Chivalric Myth and Mantuan Political Reality in the Sala del Pisanello’, Art History, vol.8, no.4, 1985, pp. 397–412.

Further reading

- Lazaris, S. "L’empereur Jean VIII Paléologue vu par Pisanello lors du concile de Ferrare – Florence", Byzantinische Forschungen, 29, 2007, p. 293-324 [1]

External links

- Medal of John Palaeologus - Victoria and Albert Museum