Mark Sykes

Colonel Sir Mark Sykes | |

|---|---|

Sykes, c. 1918 | |

| Born | Tatton Benvenuto Mark Sykes 16 March 1879 London, England |

| Died | 16 February 1919 (aged 39) Paris, France |

| Resting place | St Mary's Church, Sledmere, East Riding of Yorkshire, England |

| Education | Jesus College, Cambridge |

| Occupations |

|

| Known for | Sykes–Picot Agreement |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Spouse | Edith Gorst |

| Children | 6 |

| Father | Sir Tatton Sykes, 5th Baronet |

Colonel Sir Tatton Benvenuto Mark Sykes, 6th Baronet (16 March 1879 – 16 February 1919) was an English traveller, Conservative Party politician, and diplomatic advisor, particularly with regard to the Middle East at the time of the First World War.

He is associated with the Sykes–Picot Agreement, drawn up while the war was in progress regarding the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire by the United Kingdom, France and the Russian Empire, and was a key negotiator of the Balfour Declaration.

Early life

Born in Westminster, London, Mark Sykes was the only child of Sir Tatton Sykes, 5th Baronet, who, then a 48-year-old wealthy bachelor, married Christina Anne Jessica Cavendish-Bentinck, 30 years his junior.[1] Several accounts suggest that his future mother-in-law essentially trapped Sir Tatton Sykes into marrying Christina. They were reportedly an unhappy couple. After spending large amounts of money paying off his wife's debts, Sir Tatton published a notice in the papers disavowing her future debts and legally separating from her.

Lady Sykes lived in London, and Mark divided his time between her home and his father's 34,000 acre (120 km2) East Riding of Yorkshire estates. Their seat was Sledmere House. Lady Sykes converted to Roman Catholicism and Mark was brought into that faith from the age of three.[2]

Sledmere House "lay like a ducal demesne among the Wolds, approached by long straight roads and sheltered by belts of woodland, surrounded by large prosperous farms...ornamented with the heraldic triton of the Sykes family...the mighty four-square residence and the exquisite parish church."[3] The family farm also had a stud, where Sir Tatton Sykes bred his prized Arabs.

Mark Sykes was left much to his own devices and developed an imagination, without the corresponding self-discipline to make him a good scholar. Most winters he travelled with his father to the Middle East, especially the Ottoman Empire.

Sykes was educated at the Jesuit Beaumont College and Jesus College, Cambridge.[4] He did not finish a degree, unlike his rival T. E. Lawrence, who graduated from Jesus College, Oxford.[2] By the age of twenty-five, Sykes had published at least four books; D'Ordel's Pantechnicon (1904), a parody of the magazines of the period (illustrated by Edmund Sandars); D'Ordel's Tactics and Military Training (1904), a parody of the Infantry Drill Book of 1896 (also with Sandars); and two travel books, Dar-ul-Islam ('The Home of Islam', 1904) and Through Five Turkish Provinces (1900). He also wrote The Caliphs' Last Heritage: A Short History of the Turkish Empire,[5] the first half of which is a brief overview of political geography of the Middle East up to the Ottoman Empire while the second half is an account of the author's travels in Asia Minor and the Middle East between 1906 and 1913.[6]

At his memorial service an old friend, Aubrey Herbert, diplomat and scholar, would remember Sir Mark Sykes with affection: "An effervescent personality; he could turn a gathering into a party, a party into a festival. He bubbled with ideas, and he swept up his listeners with his enthusiasm. In addition he had a remarkable talent for sketching caricatures and for mimicry ... Mark Sykes had vitality beyond any man I have ever met. When one had been in his company one felt almost as if one had been given from the fountain of life."[7]

The Boer War, travels and Parliament

Heir to vast Yorkshire estates and a baronetcy, Sykes was not content to await his inheritance. In 1897 he was commissioned into the 3rd (Militia) Battalion of the Green Howards.[8] Sykes was sent abroad with the 5th Battalion of the Green Howards during the Second Boer War for two years, where he was engaged mostly in guard duty, but saw action on several occasions. Following the war, he was promoted to captain on 28 February 1902,[9] and returned to the United Kingdom on 15 May the same year, when the appointment was confirmed.[10] He travelled extensively, especially in the Middle East.

From 1904 to 1905 he was Parliamentary Secretary to the Chief Secretary for Ireland, George Wyndham in the last year of Balfour's administration. He made a friend of the Prime Minister, who went on to serve as Foreign Secretary during the First World War, when Sykes worked closely with him. Transferred by Balfour, he served as honorary attaché to the British Embassy in Constantinople 1905–06, at which time he began a lifetime's interest in middle eastern affairs of state.

Sykes was very much a Yorkshire grandee, with his country seat at Sledmere House, breeding racehorses, sitting on the bench, raising and commanding a militia unit, serving as Honorary Colonel of the 1st Volunteer Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment,[11] and fulfilling his social obligations. He married Edith Gorst, also a Roman Catholic, daughter of the Conservative party manager, Eldon Gorst. It was a happy union, and they had six children. Two of those children were Angela Sykes, a sculptor, and Christopher Sykes, author. Sykes succeeded to the baronetcy and the estates in 1913. Lady Sykes went on to found a VAD Hospital in Hull during the First World War.[12]

After two unsuccessful attempts, Sykes was elected to Parliament as a Unionist in 1911, representing Kingston upon Hull Central. He became close to Lord Hugh Cecil, another MP and was a contemporary of F. E. Smith, later Lord Birkenhead, and Hilaire Belloc. A JP in the East Riding, he was also elected a member of the County Council.

Sykes was also a friend of Aubrey Herbert, another Englishman influential in Middle Eastern affairs, and was acquainted with Gertrude Bell, the pro-Arab Foreign Office advisor and Middle Eastern traveller. Sykes was never as single-minded an advocate of the Arab cause as Bell, and her friends T. E. Lawrence and Sir Percy Cox. His sympathies and interests later extended to Armenians, Arabs and Jews, as well as Turks. This is reflected in the Turkish Room he had installed in Sledmere House, using the noted Armenian ceramic artist David Ohannessian as designer.

The author H. G. Wells noted in the Appendix of his 1913 publication Little Wars, an early publication about the hobby of wargaming with miniature soldiers, that he had exchanged correspondence with "Colonel" Mark Sykes about how his hobby war game might be converted into a proper "Kriegspiel" as played by the British Army and be used as a training aid for young officers. This Appendix then proceeds to set forth the modifications and additions to the original rules to convert them to this new purpose.[13]

Protégé of Kitchener

When the First World War broke out in 1914, Lieutenant-Colonel Sykes was the commanding officer of the 5th Battalion of the Green Howards. However he did not lead them into battle, as his particular talents were needed by the Intelligence department of the War Office working for Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War. Kitchener placed Sykes on Sir Maurice de Bunsen's Committee advising the Cabinet on Middle Eastern affairs.

Although Sykes never got to know Kitchener well, they shared a similar outlook, and Sykes had gained a new confidence. He soon became the dominant person on the committee, and so garnering great influence on British Middle Eastern policy, later becoming a prominent expert. For the Intelligence Unit he wrote pamphlets promoting Arab independence, fomenting revolt against the Ottoman Empire. He was introduced to Colonel Oswald FitzGerald, Kitchener's assistant secretary. London still hoped to persuade Turkey to abstain from fighting, or to join the Allies' side in the war against the Central Powers.

It was Sykes's intelligence that informed the Foreign Office that Turkey would fight alongside Germany – which Fitzgerald carried by letter to Kitchener.[14] (Turkey became a belligerent in November 1914.) Sykes only saw Kitchener briefly once in his life at York House, on which occasion he was presented with a list of points for discussion. Sykes's advice was clear: "Turkey must cease to be...should be done up to the nines and given money and food....Then premiums might be offered for camels...then a price for telegraphic insulators...then a price for interruption of Hejaz railway line and a good price for Turkish Mausers and a good price for deserters from the Turkish Army...if possible keep the whole of the Hejaz Railway in a ferment and destroy bridges".[15][16][17]

Upon Sykes's instigation, but not completely according to his wishes, the Foreign Office set up the Arab Bureau in Cairo in January 1916. Sykes designed the flag of the Arab Revolt, a combination of green, red, black and white. Variations on his design later served as flags of Jordan, Iraq, Syria, Egypt, Sudan, Kuwait, Yemen, the United Arab Emirates and Palestine, none of which except for Egypt had existed as separate nations before the First World War.[18]

With the rise of the Lloyd George ministry in December 1916, he was appointed to the War Cabinet Secretariat, and assigned to the British section of the Supreme War Council at Versailles, France.[19]

Britain's strategic conundrum

Sykes had long agreed with the traditional policy of British Conservatives in propping up Ottoman Turkey as a buffer against Russian expansion into the Mediterranean. Britain feared that Russia had designs on India, its most important colonial possession. A Russian fleet in the Mediterranean might cut British sea routes to India. British statesmen such as Palmerston, Disraeli and Salisbury had held this view. Liberal Party leader, William Ewart Gladstone, was much more critical of the Ottoman government, deploring its misgovernment and periodic slaughter of minorities, especially Christian ones. A Liberal successor, David Lloyd George, shared a progressively disdainful attitude towards the 'sick man' of Europe.[citation needed]

Compounding Britain's difficulties, France sought to secure a Greater Syria, where there were significant minorities, that included Palestine. Another ally, Italy, advanced claims to the Aegean Islands offering protection to Christian minorities in Asia Minor. Then Russian claims had to be considered, particularly with respect to control of the Straits leading from the Black Sea to the Aegean and protection of the Christian population of Turkish Armenia and the Black Sea coast. Greece coveted historic Byzantine territories in Asia Minor and Thrace, claims that conflicted with those of Russia and Italy, as well as Turkey. David Lloyd George, favoured the Greek cause. Complicating this was the desire of Zionists to have a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

Sykes set off from London[when?] on a journey of six months' duration overland across Europe to Bulgaria. He stopped at Sofia, and thence took ship to the British HQ in the Dardanelles. From Turkey, travelling to Cairo, Egypt, down the Suez Canal to Aden on the Yemen peninsula. From the Port of Aden he crossed the Indian Ocean to Simla, India, and then back to Egypt. Sykes was debriefed by the Arab Bureau at Cairo HQ. Lloyd, Herbert, and other Egyptian army officers were there. Cheetham had been replaced by Sir Henry MacMahon as High Commissioner; with the secretariat of Clayton and Storrs still in support. Sykes amused the High Commissioner with mimicry of Turks and Syrians, drawing caricatures of the General Staff. But Sykes was also on a fact-finding mission reporting back to the De Bunsen Committee, to which he had been appointed by Kitchener in March 1915.[citation needed]

In mid-July 1915 the Emir Abdullah finally broke silence after 6 months to reply to the proposals which Sir Ronald Storrs had put to his father the Grand Sharif. Sykes had left Cairo and travelled through Syria. By 8 December 1915 he returned to England, having also met T.E. Lawrence, to gain support for an Arab Revolt. Lawrence called Sykes "the imaginative advocate of unconvincing world movements... a bundle of prejudices, intuitions, half-sciences. His ideas were of the outside; and he lacked patience to test his materials before choosing the style of building .... He would sketch out in a few dashes a new world, all out of scale, but vivid as a vision of some sides of the thing we hoped". Lawrence thought him a good fellow, but a sadly unreliable intellect.[20] Gertrude Bell and Lawrence were less congenial, and not his favourite people in the Arab Bureau.[citation needed] Sykes remained a purist who shunned democratic progress, instead vesting his energy in an indomitable Arab Spirit. He was a champion of the Levantine tradition, of a mercantile trading empire, finding the progressive modernisation in the West totally unsuited to the desert kingdoms.[21]

This meant the Alexandretta Plan to roll up Syria, in order to reshape the Middle East on nationalist lines.[22] On 16 December he met the War Committee of the Cabinet at 11 am. Although others were present, only Lloyd George, Arthur Balfour, H. H. Asquith and Kitchener spoke.[citation needed]

It was Sykes's special role to hammer out an agreement with Britain's most important ally, France, which was shouldering a disproportionate part of the effort against Germany in the First World War. His French counterpart was François Georges-Picot and it is generally accepted that Picot got a better deal than expected. (See the Sykes-Picot Agreement.) Sykes came to feel this as well and it bothered him.[citation needed]

The Balfour Declaration

Late morning 16 December 1915 Sir Mark Sykes arrived at Downing street for a meeting to advise Prime Minister Asquith on the situation with the Ottoman Empire. Sykes made a "statement to the War Council".[23] Over the last four years Sykes had become the principal British expert on Turkish affairs.[24] Elected as Conservative MP in Hull in 1911, his maiden speech in November 1911 was about British foreign policy in the Middle East and North Africa.[25] Sykes brought a map and a three-page document on his thoughts of middle eastern policy.[22]

In Caliph's Last Heritage Sykes was appalled by the filth and squalor of Aleppo and Damascus. Whilst he praised the French for inventing the set square for the illiterate Arab, he glossed over the German contribution to building railways that enabled Arabs to travel; Sykes stressed the negative aspects of social squalor. Sykes underestimated the Turks[26][22] but W Crooke's review surmised that the facts he collected would be helpful to resolve the Eastern Question.[27] Across Whitehall, Sykes became known as "the Mad Mullah", even so he was summoned to No. 10, as rumours spread he was to become a Joint Cabinet secretary.[28] Lloyd George hated the corrupted Ottomans and could not wait to seize imperial power from them; while Balfour at the admiralty, was the only non-bellicose member. Sykes proposed that the issue of Syria be settled as quickly as possible with France. It was reported on 16 August that Sykes was attending the Stockholm Conference as a paid up member of the Seamen & Firemen's Union, "but it cannot be known he carries their guarantee."[29] Sykes remained loyal to Maurice Hankey and the Coalition government throughout. He alerted Hankey, the Cabinet Secretary, to General Maurice's agitation against the Prime Minister and Haig, as well as criticizing the King's part in the war. Sykes was concerned that rumours were swirling around H. A. Gwynne, The Morning Post's editor, to the effect that Robertson was plotting with Asquith to bring back the old government.[30]

Evidence suggests that Sykes had a hand in promoting the Balfour Declaration to the Cabinet issued on 2 November 1917.[31] Sykes was convinced that the Jews held vast and sinister powers to manipulate world events and in March 1916 he wrote that with "great Jewry against us, there is no possible chance of getting the thing through [i.e winning the war]-it means optimism in Berlin, dumps in London, unease".[32] In March he had visited Palestine to meet Chaim Weizmann; Sykes was clearly, with proviso, converted to the cause of Zionism.[33] On 7 November 1917, the Bolsheviks under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin overthrew the Russian Provisional Government. Sykes believed that the Bolsheviks were mostly Jewish, and the best way of keeping Russia in the war was for Britain to make a pro-Jewish gesture.[34] The Balfour Declaration stated that: "His Majesty's Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine..."

In June 1918, the 14th Division was ordered to remove to Italy from Palestine. Sykes told Hankey the General Staff had expected him to be in Gaza by Christmas and not Damascus. Moslem troops, Picot had mentioned were unreliable but Allenby would not be advised by any Political Officer who said the cross-border raids were upsetting the Arabs.[35]

Sykes had begun to change his views on Zionism in late 1918. Diplomat and Sykes's biographer, Shane Leslie, wrote in 1923:

From being the evangelist of Zionism during the war he had returned to Paris with feelings shocked by the intense bitterness which had been provoked in the Holy Land. Matters had reached a stage beyond his conception of what Zionism would be. His last journey to Palestine had raised many doubts, which were not set at rest by a visit to Rome. To Cardinal Gasquet he admitted the change of his views on Zionism, and that he was determined to qualify, guide and, if possible, save the dangerous situation which was rapidly arising. If death had not been upon him it would not have been too late."[36]

Death

Sykes was in Paris in connection with peace negotiations in 1919. At the conference, a junior diplomat present, Harold Nicolson, wrote in his diary the day after Sykes's death: "...It was due to his endless push and perseverance, to his enthusiasm and faith, that Arab nationalism and Zionism became two of the most successful of our war causes..."[37]

He died in his room at the Hôtel Le Lotti near the Tuileries Garden on 16 February 1919, aged 39, a victim of the Spanish flu pandemic. His remains were transported back to his family home at Sledmere House (in the East Riding of Yorkshire) for burial. Although he had been a Roman Catholic, he was buried in the churchyard of the local Anglican St. Mary's church in Sledmere.[38] Nahum Sokolow, a Russian Zionist colleague of Chaim Weizmann in Paris at this time, wrote that he "... fell as a hero at our side."

He was succeeded by his son, Sir Richard Sykes, 7th Baronet (1905–1978). Another son, Christopher Sykes (1907–1986), was a distinguished author and official biographer of Evelyn Waugh. Sir Mark's great-grandchildren include the New York-based fashion writer and novelist Plum Sykes and her twin sister, Lucy Sykes (Mrs. Euan Rellie), and their brother, writer Thomas (Tom) Sykes.

Sledmere House is still in the possession of the family, with Sir Mark's eldest grandson Sir Tatton Sykes, 8th Baronet, being the current occupant. Another brother, Christopher Sykes, or his son, will eventually inherit the baronetcy.

Honours and arms

He received during his service no British honours but he was made a Commander of the Order of St Stanislas by Tsarist Russia and held the Order of the Star of Romania.[38]

|

|

Exhumation for biological research

In 2007, 88 years after Sir Mark Sykes died, all the living descendants gave their permission to exhume his body for scientific investigation headed by virologist John Oxford. His remains were exhumed in mid-September 2008.[40] His remains were of interest because he had been buried in a lead-lined coffin, and this was thought likely to have preserved Spanish flu viral particles intact. Any samples taken are to be used for research in the quest to develop defences against future influenza pandemics. The Spanish flu virus itself became a human infection by a mutation of an avian virus called H1N1.

There are only five other extant samples of the Spanish flu virus. Professor Oxford's team was expecting to find a well-preserved cadaver. However, the coffin was found to be split because of the weight of soil over it, and the cadaver was found to be badly decomposed. Nonetheless, samples of lung and brain tissue were taken through the split in the coffin, with the coffin remaining in situ in the grave during this process.[41] Soon afterwards, the open grave was sealed again by refilling it with earth.

Legacy

Sykes is a major feature in Balfour to Blair, a documentary about the history of British involvement in the Middle East.[42]

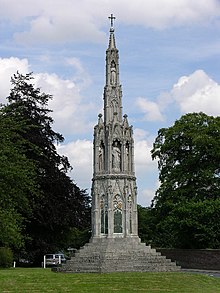

The Sledmere Cross takes the form of an Eleanor Cross and is a true folly that Sir Mark Sykes converted into a war memorial in 1919. He added a series of brass portraits in commemoration of his friends and the local men who fell in the war. He also added a brass portrait himself in crusader armour with the inscription Laetare Jerusalem (Rejoice, Jerusalem).

Sykes also designed the Wagoners' Memorial to the men of the Wagoners Special Reserve, a Territorial Army unit that he raised in 1912, composed of farm labourers and tenant farmers from across the Yorkshire Wolds intended for war service as drivers of horse-drawn wagons.[43]

Notes

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ a b "Sykes, Sir Mark". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36394. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Leslie, Mark Sykes, p.6

- ^ Fromkin, David (1989). A Peace to End All Peace. New York: Owl Books. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-8050-6884-9.

- ^ "The Caliphs' Last Heritage complete online text". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ^ "The Caliphs' Last Heritage bibliographical information".

- ^ Aubrey Herbert, a tribute to Sykes at his memorial service, SRO, HP DD/HER/53

- ^ "The Yorkshire Regiment, WW1 Remembrance".

- ^ "No. 27422". The London Gazette. 4 April 1902. p. 2282.

- ^ "The War – Troops returning home". The Times. No. 36753. London. 28 April 1902. p. 8.

- ^ Army List

- ^ "Hull's WWI Hospitals and Charities". Kingston upon Hull War Memorial 1914-1918. 26 February 2021. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ pg 101, Appendix, Little Wars,

- ^ Schneer, p.45

- ^ Sykes to Herbert, spring 1915, SRO, HP, DD/HER/34

- ^ Meyer, Karl Ernest; Brysac, Shareen Blair. Kingmakers: The Invention of the Modern Middle East. W. W. Norton & Company, 2008, p. 203.

- ^ Schneer, Jonathan. The Balfour Declaration: The Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict. Random House Publishing Group, 2010, p.383

- ^ Easterly, William (2006). The White Man's Burden. New York: Penguin. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-1012-1812-9.

A small sign of the artificiality of the Arab revolt is that Mark Sykes himself designed the flag of the Arabs as a combination of green, red, black, and white. Variations on this design are today the official flags of Jordan, Iraq, Syria, and the Palestinians.

- ^ Amery, Leopold, "My Political Life, Vol. II", pg. 92

- ^ T E Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Introduction. Foundations of Revolt. Chapter VI p. 17; Charles Townshend, When God Made Hell: The British Invasion of Mesopotamia and the Creation of Iraq, 1914–1921, p. 263

- ^ E Kedourie, England and the Middle East, chap.3; Townshend, p.267

- ^ a b c Barr, James. A Line in the Sand: Britain, France and the struggle that shaped the Middle East. Part One. "The Carve-up 1915–1919" 1. "Very Practical Politics". Simon and Schuster, 2011

- ^ TNA, FO 882/2, Sykes to Clayton, 28 December 1915;

- ^ N N E Bray, Shifting Sands, (London 1934), pp.66-7; Barr, A Line in the Sands

- ^ HC Deb 27 November 1911 vol 32 cc98-105

- ^ Edwin Pears, review of 'The Caliphs Last Heritage', EHR, vol.31, no.122 (April 1916), p.300

- ^ Review in 'Man' magazine, vol.17, (January 1917), p.24

- ^ "...certain statements that Sir Mark Sykes and Amery are to be joint secretaries with me. I wished at once to make a formal announcement about the secretariat, but Lloyd George would not sanction it...." Sir Maurice Hankey, Diary, 17 January 1917, I, p.352.

- ^ Hankey, Diary, 16 August 1917, p.427

- ^ Hankey, 8 May 1918, I, p.542

- ^ Balfour Declaration. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 12 August 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ Levene 2011, p. 344.

- ^ C P Scott, Diaries, pp.271-2

- ^ Levene 2011, p. 344-345.

- ^ Hankey, Diary, I, p.563

- ^ Leslie 1923, p. 284.

- ^ Walter Reid (1 September 2011). Empire of Sand: How Britain Made the Middle East. Birlinn. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-0-85790-080-7.

- ^ a b [1] Commonwealth War Graves Commission Casualty Record, Sir Mark Sykes. The entry does not mention his other given forenames.

- ^ Debrett's peerage & baronetage 2003. London: Macmillan. 2003. p. 985.

- ^ "Body exhumed in fight against flu". BBC. 16 September 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- ^ BBC Four documentary. In Search of Spanish Flu

- ^ "Balfour to Blair". Aljazeera. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ Historic England. "Wagoners' Memorial (1161354)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

Further reading

- Adelson, Roger D. (1975). Mark Sykes: Portrait of an Amateur. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Amery, Leopold (1953). My Political Life, Volume II, War and Peace (1914-1929). London: Hutchinson.

- Barr, James (2011). A Line in the Sand: Britain, France, and the Struggle that Shaped The Middle East. London: Simon & Schuster.

- Berdine, Michael. (2018) Redrawing the Middle East: Sir Mark Sykes, Imperialism and the Sykes-Picot Agreement (I. B. Tauris, 2018).

- Capern, Amanda L. "Winston Churchill, Mark Sykes and the Dardanelles Campaign of 1915." Historical Research 71.174 (1998): 108–118.

- Daly, M.W. (1997). The Sirdar: Sir Reginald Wingate and the British Empire in the Middle East. Philadelphia.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Darwin, John (1981). Egypt and the Middle East Imperial Policy in the Aftermath of the War, 1918–22. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Fitzgerald, Edward Peter. "France's Middle Eastern ambitions, the Sykes-Picot negotiations, and the oil fields of Mosul, 1915-1918." Journal of Modern History 66.4 (1994): 697–725. online

- Fisher, John (2002). Gentleman Spies: Intelligence Agents in the British Empire and Beyond. Stroud.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Fromkin, David (1990). A Peace To End All Peace. New York: Avon Books.

- Kedourie, Elie (1976). England and the Middle East. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Levene, Mark (2011). "The 'Jewish Question' and its impact on International Affairs, 1914-39". In Frank McDonough (ed.). The Origins of the Second World War: An International Perspective. London: Continuum.

- Leslie, Shane (1923). Mark Sykes: His Life and Letters. London: Cassell and Company.

- Louis Massignon, Eloge mortuaire (in English) de Mark Sykes, in Opera minora. Textes recueillis, classés et présentés avec une bibliographie, Beyrout, 1963.

- Meyer, Karl E. and Shareen Blair Brysac (2008) Kingmakers: the Invention of the Modern Middle East. New York: Norton. pp 94–126.

- Morris, Benny (2001). Righteous Victims. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 9780679744757.

- Norton, W.W. (2008). Kingmakers: the Invention of the Modern Middle East, Karl E. Meyer and Shareen Blair Brysac. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Schneer, Jonathan (2010). The Balfour Declaration: The Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict. London: Bloomsbury.

- Sykes, Christopher Simon (2005). The Big House: The Story of a Country House and Its Family. London: Harper Perennial.

- Sykes, Christopher Simon (2016). The Man Who Created the Middle East: A Story of Empire, Conflict and the Sykes-Picot Agreement. London: William Collins.

- Townshend, Charles (2010). When God Made Hell: British invasion of Mesopotamia and the Creation of Iraq, 1914–1921. Faber and Faber.

- Wallach, Janet (1999). Desert Queen. New York: Anchor Books. ISBN 9780385495752.

- Wilson, Trevor, ed. (1970). The Political Diaries of C.P.Scott 1911–1928. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)