Madrid, Zaragoza and Alicante railway

Compañía de los Ferrocarriles de Madrid a Zaragoza y Alicante | |

| |

| Abbreviation | MZA |

|---|---|

| Predecessor | |

| Successor | RENFE |

| Formation | December 31, 1856[1] |

| Founder | José de Salamanca Mayol; Society Rothschild. |

| Dissolved | July 1, 1941 |

| Type | S.A. |

| Headquarters | Madrid,[1]

|

| Products | Passenger and Freight Rail Transport |

| Services | Transport, Rail transport |

| Budget | 456000000 reales in 1856[1] |

| Staff | 12000[2] |

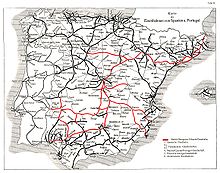

The Madrid, Zaragoza and Alicante railway (MZA) - also known in Spanish as Compañía de los ferrocarriles de Madrid a Zaragoza y a Alicante - was a Spanish railway company founded in 1856 that became one of the most important companies in the railway sector, along with its great rival, the Compañía de los Caminos de Hierro del Norte de España (known simply as "Norte".)

The rivalry between MZA and Norte stemmed from competing financial families at the time, namely the Rothschilds and Pereires. MZA rapidly expanded its railway concessions to encompass key routes in Extremadura, New Castile, Andalusia, and Levante, thereby gaining control of a significant market. MZA also constructed Atocha Station in Madrid, del Carmen Station in Murcia, Campo Sepulcro (later El Portillo Station) in Zaragoza, and Plaza de Armas Station in Seville, which is also recognized as Cordoba Station and presently transformed into a shopping center.

At the turn of the 20th century, MZA reached its operational peak, but soon after, the company was hit by crisis. The Spanish Civil War marked the end for MZA, as the company was condemned when the Spanish State nationalized all broad gauge railways in 1941. As a result, MZA ceased to exist.

Basic chronology

- On December 31, 1856, the Compañía de los Ferrocarriles de Madrid a Zaragoza y Alicante was founded by José de Salamanca Mayol, the representatives of the Rothschilds in Spain, etc.

- On May 16, 1863, the Madrid to Zaragoza Railway, which started in 1858, was finished, concluding the construction of rail lines during that era.

- On April 25, 1865, the Albacete to Murcia and Cartagena railway line was inaugurated, marking the second railway line in the Spanish Levant.

- On October 5, 1875, the Cordoba-Seville Railway was acquired, allowing for domination of the Guadalquivir valley and control over one of Spain's most important lines. This acquisition fulfilled one of the company's aspirations since the 1860s.

- On April 8, 1880, the Madrid-Ciudad Real-Badajoz Railway annexation introduced a new railway track to Ciudad Real and provided a connection to Extremadura and a route to Portugal.

- On January 16, 1885, the Mérida-Seville Railway was opened, signaling the conclusion of the expansion in the Extremadura region and connecting it with the Andalusian lines that had already been under control for some time.

- On December 8, 1892, the renovation of Atocha Station was completed, making it the main station of MZA and one of the most important in the country.

- On January 1, 1898, the merger of MZA and TBF became effective, as per the agreement signed several years earlier. The Madrid-Zaragoza-Alicante Company expanded its network in Catalonia and acquired significant railway traffic. The company's growth period ended with this merger.

- In 1925, the Catalan Network was definitively integrated into the MZA structure.

- In 1929, MZA inaugurated the Barcelona Terminus Station, its last major project before experiencing decline.

- On August 3, 1936, the Republican government nationalized the railway network it controlled during the Spanish Civil War. Consequently, the MZA was absorbed by the Red Nacional de Ferrocarriles in the area loyal to the Second Republic. Directors and managers who escaped to the rebel zone attempted to regain their previous power, but the military ultimately managed all aspects of the railway. Much of MZA's material and infrastructure were severely damaged and destroyed during the war.

- On July 1, 1941, the MZA Company ceased to exist, and its entire network, facilities, and rolling stock were incorporated into the newly established RENFE.

Background

The company's origins can be traced back to the Madrid-Alicante railway concession, which originally belonged to the Compañía de Camino de Hierro de María Cristina, a company in which the Crown was involved, although at the time it was only an idea. Construction of this railway was in three stages, beginning with the inauguration of the Madrid-Aranjuez line in 1851 and its subsequent extension to Almansa and later to Alicante. José de Salamanca Mayol, who would become a prominent Spanish businessman in the 19th century, was involved in this construction project. With control over the completed line in 1856, the Marquis of Salamanca connected with wealthy French businessmen already invested in the railway industry in Spain.[3]

The Rothschilds and others foresaw the creation of the Sociedad Española Mercantil e Industrial, which had Daniel Weisweiller and Ignacio Bauer as representatives, both of whom would play key roles in the future company. On the opposite side were the Duke of Morny and several French administrators of the Chemin de Fer du Grand Central. In the mid-1850s, Spain had few railway lines, despite significant projects in the previous decade aimed at linking all provincial capitals in the country. In 1845, the Spanish ambassador in London recommended and certain banks supported the proposition of a railway line connecting Madrid, Zaragoza, Pamplona, and Barcelona. A businessman took the initial measures for the State to grant it.[4]

The ambitious Madrid-Zaragoza link project was abandoned prematurely due to various reasons. Despite this setback, the project did not fade away. The State declared the line of general interest and made its construction a priority starting from 1851. In 1855, more favorable conditions were offered under the law to encourage potential concessionaires. On February 24, 1856, the Madrid-Zaragoza railway concession was auctioned to the mentioned companies. The concession marked the potential start of a major route from Madrid to the border through the Pyrenees. The Madrid-Zaragoza line and numerous concessions in France enabled the creation of a vast international network. José de Salamanca, owner of Madrid-Aranjuez Railway, recognized a promising business opportunity and contacted the Rothschilds to propose merging their partially-operational Mediterranean line with a joint concession.[3] However, José Campo was also interested in the business.[5] The concession for the line was awarded on February 24, 1856, with five proposals on the table:

- Sociedad Española Mercantil e Industrial (Rothschild)

- Sociedad de Crédito Mobiliario Español (Péreire brothers)

- José de Salamanca

- José Campo y Mateu

- Chemin de Fer du Grand Central Group

The award was won by the latter group, which in its proposal asked for fewer subsidies from the State. In fact, it gained an advantage after the Rothschilds' agreement with the Marquis of Salamanca. The new company was formed by the Duke of Morny, owner of the Chemin de Fer du Grand Central; Weisweller and Baüer, representatives of the Rotschilds; and José de Salamanca, who contributed the Alicante line. The understanding that resulted between some of the bidders led to the birth of the new company in just a few months.[6]

Establishment

When the Madrid-Zaragoza railway was auctioned, it also sparked the idea of forming a new railway company to combine that line with the Madrid-Alicante line, which was under the ownership of the Marquis of Salamanca. Several names were proposed, including Compañía de los Ferrocarriles de los Pyrenees a Zaragoza y el Mediterráneo. However, the final choice was "Compañía de los Ferrocarriles de Madrid a Zaragoza y a Alicante" (Madrid, Zaragoza and Alicante railway, MZA), which was officially established on December 31, 1856, with a capital of 456 million reales divided into 240,000 shares.[1]

The company's Board of Directors assembled on January 16, 1857. During this meeting, Alejandro Mon was elected president, and José de Salamanca became the vice-president. A central management committee was also formed in Paris. At that point, the company had established the Atocha station in Madrid, and the Madrid to Almansa line was operational, while the section to Alicante was under construction.[1]

Start of operations

Soon after its establishment, the company focused entirely on constructing the railway to Zaragoza. However, the preliminary project originally proposed building a Madrid station near Puerta de Recoletos (nowadays Plaza de Colón). Despite this, the company lacked interest in constructing a new station in Madrid. Consequently, the construction of the Aragon line commenced from Atocha station, and it proceeded without significant difficulties. In 1859, the railway had already reached Guadalajara, prompting MZA to establish a stagecoach service between the city and Zaragoza. By 1861, with further construction underway, MZA entered into an agreement with Compañía del Ferrocarril de Zaragoza a Pamplona to operate a Madrid-Paris service via Tudela, Pamplona, and Bayonne, designed to compete directly with Compañía de los Caminos de Hierro del Norte de España, and lasting 54 hours.[7]

From the outset, MZA's leaders aimed to construct new branches to La Mancha, Extremadura, and even Andalusia. The Government developed a construction program and tendered some line contracts in support of this objective. On March 30, 1859, a law was passed to establish a new Andalusian line that would run from Manzanares to Malaga and Granada. The MZA secured a concession for the first two sections of this line on October 20, 1860. The auction at Alcazar de San Juan was scheduled for April 8, 1859. For unclear reasons, Bauer and Jose de Salamanca decided to employ the services of a front man - the wealthy local landowner, Marquis of Villamediana - who successfully obtained the concession against banker Guilhou. Finally, as agreed, the MZA received the concession on April 20. To conclude, on November 8, 1859, José de Salamanca was granted permission to construct a railway between Albacete and Cartagena. The transfer of this project to the MZA was authorized on April 30, 1860, by Royal Decree. Even though the track reached Guadalajara in the spring of 1859, it had to be transferred to a stagecoach service in Alhama de Aragon for a substantial period. The missing link was finally completed in May 1863. The initial years of operation were troublesome, and the initial French directors of the company were determined to enhance performance and turn a profit.[8]

Expansion of network in La Mancha and Andalusia

From the outset of the company, there were plans to expand the network to the southern regions in preparation for acquiring key routes to Andalusia and its ports, as well as through La Mancha. In December 1858, shortly after its establishment, the company made its initial acquisition, the Compañía del Ferrocarril de Castillejo a Toledo, owned by the Marquis of Salamanca. However, this annexation only entailed acquiring a small branch line to the historic city of Toledo. The La Mancha and Extremadura lines will follow soon, as well as those of Andalusia, which could commence in the great Madrid-Alicante line, the major Mediterranean line that runs through much of the lands of La Mancha.[9]

Starting from Alcázar de San Juan station as a base, the railway line to Ciudad Real was established. The auction for the railway was announced on April 8, 1859. Initially, the Company planned to participate in the auction but later decided to do so indirectly through its advisors Salamanca and Baüer, who in turn negotiated an agreement with the Marquis of Villamediana. He presented himself at the auction and won by reducing his bid for the State subsidy from 18 to 15 million dollars. The concession was granted to Antonio de Lara, Marquis of Villamediana, who then ceded it to MZA on April 20. Construction began immediately.[6]

Construction on the line progressed smoothly due to the absence of challenging geographic features. The stretches from Alcázar to Manzanares were completed in June 1860, followed by Daimiel on October 1 of that year. Finally, Ciudad Real was reached on March 14, 1861, even as work on the Zaragoza line was yet to be completed.[6]

With the railway passing through Manzanares, the company decided to use it as the starting point for a derivation towards Andalusia. This wasn't the first time the idea of connecting Madrid to the Andalusian region had been discussed, far from it. There was already a precedent in 1856 when the Grand Central received a concession to start from Madrid-Almansa and enter the province of Jaen, then continue to Cordoba through the valley of Guadalquivir. This project ultimately failed, leading to the MZA launching a new project that received approval through a new Royal Order on March 30, 1859. This new project divided the railway route into four sections:

However, the MZA was only interested in the first two sections, and was concerned that an independent auction would lose it Section II, which was easier to build. With the aid of the government, it consolidated sections I and II, and scheduled an auction on October 20, 1860, which the influential company confidently won. Sections III and IV would be retained by Jorge Loring y Oyarzábal and become a part of Compañía del Ferrocarril de Córdoba a Málaga. MZA was extremely confident in winning the auction as work started between Manzanares and Torrenueva merely days later.[8]

Cartagena's position on the Mediterranean and its military arsenal made it significant to both the railway and MZA. Several alternatives were studied for the construction of a branch line to Murcia and Cartagena from the Madrid-Alicante line since 1852. Eventually, the concession for the railway which would pass through Albacete was put up for auction by the government in 1860. José de Salamanca won the concession, as he had on previous occasions, and subsequently transferred it to MZA. Despite controversies around the connection point of the branch line that would ultimately lead to Cartagena, Albacete was able to succeed and by 1863, several sections had already been inaugurated, including the Murcia-Cartagena section. Although the railway service was already operating in the southern section of the line, discussions cleared the way for fast-paced work to be completed in the northern section. The entire 240-kilometer line was officially completed on April 27, 1865. The junction point, which had been subject to much controversy, was ultimately located at Chinchilla, near Albacete.[10]

Zaragoza railway completion

By 1859, the railway had extended up to Guadalajara. Subsequently, a combined service of stagecoaches linked with the Aragonese capital. Construction work continued in the ensuing years despite facing some economic and geographical challenges, until finally reaching Aragonese lands. The railway had already made its way to Alhama de Aragon by the start of 1863. Soon afterwards, it reached Zaragoza, leading to the official inauguration of the railway line on May 16, 1865. Although the line only extended to Zaragoza at present, the city was already benefiting from the traffic that passed through Lleida from Barcelona. Nonetheless, MZA did not yet have a railway that directly connected it with the city of Barcelona.[11]

Operations (1865-1875)

These years were marked by crisis rather than good results. This period coincided with the economic downturn at the end of Isabella II's reign, as well as her widespread disapproval among many sectors of Spanish society. The Glorious Revolution erupted in 1868, leading to the Six-year Democracy. Following the rebels' success in Alcolea, the queen was forced into exile, and a temporary government was established. The next five years experienced the rule of Amadeo I, the declaration of the First Republic, the onset of the cantonal rebellion, and persistent political instability. In 1875, the Bourbons regained the monarchy under Alfonso XII. This tumultuous political climate affected the company's financial records and future. In 1865, the company experienced severe financial difficulties. These struggles were compounded by a fierce dispute with the Compañía del Norte. However, the greatest threat to the company's survival came in 1868 with an economic crisis. Despite these challenges, Cipriano Segundo Montesino, the first Spaniard to hold this position, assumed management of the company in the following year. Through his leadership, he successfully revived and ultimately saved the company by addressing the root of the problem.[12]

After one year in office, he made some changes to train operations and reduced expenses while increasing operating profits. He also reached an agreement with Norte for traffic distribution and other matters. In 1871, he replaced the old iron rails with steel rails resulting in dividends for shareholders in 1873. The MZA had a network spanning 1428 km and was poised for expansion, not through new construction, but by acquiring and incorporating existing lines facing economic hardship.[13]

Railway expansion after 1875

The revolution of 1868 and the financial crisis that the company endured caused the directors to refrain from requesting new concessions. By 1875, after the most significant challenges had been overcome, the MZA could enter a new phase of expansion, resulting in the addition of roughly 1,189 km of existing lines to the MZA network.

The initial rescue had strong political implications and served as a means of reconciliation with Norte. The latter agreed to give up its Andalusian firm, and in return, the MZA did not hinder the recovery of the ZPB. The merger ultimately involved Compañía de los Ferrocarriles de Zaragoza a Pamplona y Barcelona by Norte. The Cordoba-Seville Railway Company was in dire straits for the future, prompting it to seek a merger by engaging in talks with other railway companies. In contrast to its terrible relations with the Seville-Jerez-Cadiz Railway Company, the small company had established good relations with MZA. Thus, on October 5, 1875, MZA acquired Compañía del Ferrocarril de Córdoba a Sevilla and its 132 kilometers of operational lines, along with the line from La Reunión mines to Villanueva del Río y Minas. This allowed Madrid to Zaragoza and Alicante Company to connect this railway with its own, which reached Cordoba and enabled access to the Andalusian region's capital.[14]

The MZA acquired the Compañía de los Ferrocarriles de Sevilla a Huelva in 1877, following negotiations that began in 1876. This expansion included 111 km of partly completed lines that faced significant difficulties and would not be finished until 1880. The acquisition also included the use of the Huelva station, which was commissioned in 1880 and remained operational with RENFE until 2018. The MZA executives, who owned railways and had a foothold in various Mediterranean ports, believed that establishing a port on the Atlantic would boost their network traffic by expanding operations to additional countries. Unfortunately, this aspiration would remain unfulfilled.[15]

The Ciudad Real to Badajoz line was opened on November 22, 1866, under the ownership of the Compañía de los Caminos de Hierro de Ciudad Real a Badajoz. Subsequently, the company expanded its network by adding a new branch to Madrid, which was finished by 1879. Nevertheless, the company had shifted towards a business model that impeded its long-term survival. Since the beginning of 1879, both companies have been entering into agreements, including one for the distribution of traffic. Eventually, this led to the annexation by MZA. On April 8, 1880, the absorption of the Compañía de los Caminos de Hierro de Ciudad Real a Badajoz increased the network by an additional 510 km and most importantly, provided an exit to Portugal.[16]

Delicias station, formerly known as the Compañía de Ciudad Real-Badajoz station and located in the capital, was not acquired by MZA due to their ownership of the much larger Atocha station. Instead, they sold Delicias to the recently established Compañía de los Ferrocarriles de Madrid a Cáceres y Portugal, who ultimately acquired it.[16] The merger policy was finalized with the rescue of the Compañía del Ferrocarril de Mérida a Sevilla in 1880, although it was granted with the concession since the line works had not begun yet. By 1881, both ends of the line were completed and operational. Finally, on January 16, 1885, the entire line between Mérida and Seville opened to the public. The joining of the Ciudad Real-Badajoz and Cordoba-Seville-Huelva lines marked the completion of MZA's southern annexation phase, making this annexation pivotal.[17]

Operations (1875-1895)

In addition to the annexations and the expansion of the railways, the MZA carried out a policy adapted to the situation of the country. During this period, known as the Restoration, there was a significant economic upturn, with strong commercial activity and, above all, strong industrial expansion. This situation required the railways to adapt the existing rolling stock of the companies and to improve the network and facilities.[18] In 1876, the company purchased 400 new wagons, which eventually increased to 1000 units. In the same period, MZA underwent modernization which included the commissioning of the first express between Madrid and Seville in 1878. The following year, another express began operating between Madrid, Lleida, and Barcelona. Wagons-Lits equipment was put into service on the Andalusia express on April 16, 1883, and a successful braking system test was conducted on the same express on May 8, 1886.[18]

The railway construction from Aranjuez to Cuenca began in 1884. The line had already been designated for construction by state concession prior to 1880 and was acquired by MZA from the previous construction company. With MZA, the construction was fast and the circulation of trains was ready on September 5, 1885. The line's operation was subpar because it ended in Cuenca rather than continuing to Utiel, which already had a railway, and directly on to Valencia. Despite requests from provincial figures, MZA disregarded them and continued in this manner until well into the 20th century.[19] MZA also planned to construct another rail link with the North, which would begin at Ariza (on the Madrid-Zaragoza railway) and extend to Valladolid, passing through Aranda de Duero.[20]

Conceived as a strategic railway line according to government plans, it became operational on January 1, 1895, marking the end of MZA's railway construction.[20] In contrast, MZA undertook improvements to renovate the Atocha station around 1880. The aim was to transform the small and antiquated building, which was inadequate to meet the needs of the time. In 1889, the company initiated the extension of Madrid-Atocha station after the City Council of Madrid completed works in the area, which until then had been abandoned. The canopy that exists today, with multiple platforms reflecting the volume of trains moving at that time, was finished in 1892.[21]

Expansion into Catalonia

In 1885, the civil engineer Eduardo Maristany Gibert (1855-1941) (grandson of Manuel Gibert, president of the primitive Compañía del Camino de Hierro de Barcelona a Mataró) joined the Compañía de los ferrocarriles de Tarragona a Barcelona y Francia (TBF). At the time, the TBF was building a direct line from Barcelona to Zaragoza, on a route much further south than the one operated by the Compañía del Norte via Lleida and Manresa. TBF was already in communication with MZA regarding a potential merger. TBF found it more practical to merge its new line connecting Zaragoza to Barcelona via Caspe with MZA's line connecting Madrid to Zaragoza, creating a single company to link the two main Spanish cities. This approach differed from TBF's original plans, which were inherited from the now-defunct Compañía de los Ferrocarriles Directos de Madrid y Zaragoza y Barcelona, absorbed by TBF.[22]

A branch line was established as a result of the merger agreements and commenced service on June 15, 1887. The line integrated the Valls-Villanueva-Barcelona (VVB) line into the city's network of links by connecting a point of the ex-VVB near the Llobregat River with the Bordeta fork on the line from Tarragona and Martorell that led to Aragon Street. With the completion of this railway link in 1887, the "Catalan eight" was established. It enabled train travel from Barcelona to different locations in the province of Girona, along the coast (Mataró) or inland (Granollers). Moreover, this connection extended southwards to several towns in the province of Tarragona, along the coast (Villanueva y Geltrú - VVB line) or inland (Martorell - "Centro" line).[23] Prior to the partnership, it was agreed that MZA would construct the 254 km Valladolid-Ariza Railway line to establish a stronghold in Castilla la Vieja, a region traditionally controlled by Compañía del Norte. Similarly, TBF would be responsible for the completion of the direct line from Caspe.[23]

However, Caminos de Hierro del Norte was interested in acquiring TBF, particularly after having acquired Sociedad de los Ferrocarriles de Almansa a Valencia y Tarragona, which was the next step. It attempted to halt the ongoing negotiations, but MZA countered with a bond issue on the Paris market. Once sufficient funds were raised, MZA was able to obtain TBF and ultimately succeeded in winning the wager against Norte.[4]

In 1891, an agreement was signed in the French capital, leading to the expansion of the MZA network many kilometers to the Northeast in 1898. Despite purchasing TBF, it did not disappear but rather remained. Due to the inability to immediately harmonize the customs, signaling systems, and loading gauges of the two companies, a certain level of differentiation persisted between the Old Network (referring to the original MZA) and the Catalan Network (formerly known as TBF).[24]

20th century

Operations (1898-1936)

By the turn of the century, MZA had undergone considerable transformation. It had expanded from 287 kilometers of track and 37 locomotives in 1856 to 3679 kilometers of track, 392 locomotives, 9,000 cars and wagons, and almost 11,000 employees by 1900.[25] At the start of the 20th century, MZA and MTM (La Maquinista Terrestre y Marítima) had a strong economic relationship. MTM was frequently placing orders with MZA for materials, making them a regular client. This caught the attention of Madrid-Alicante, who considered buying shares in MTM to gain a percentage of the company and secure better prices for future orders.[25]

The integration of the Catalan Network progressed as the century progressed, and this became more evident when the Traction Service was governed entirely from Madrid from 1908 onwards. In 1925, the two entities were definitively united. A gradual modernization of the network and facilities began, in accordance with the new situation in the new century. On the one hand, the construction of double track began on some sections of the MZA network: it already existed between Barcelona and Molins de Rey with the TBF, while in 1900 a second track was added to the section between Barcelona and Mataró.[26] The experience was repeated in the central region, specifically in the Madrid-Getafe section, in 1913. The following year, the double track extended till Alcázar de San Juan. The network modernization also covered other areas such as marshalling yards and freight stations, which were independent of the large passenger stations' traffic. Among these, the Barcelona-Morrot station, which opened in 1917, and located next to the port of Barcelona, was remarkable. It was equipped with advanced technology for processing and storing goods.[26]

MZA was not exempt and, like other companies, needed to adjust prices to the current situation. As a result, many pending reforms, as well as the modernization of facilities and rolling stock, were delayed or cancelled. This led to a critical situation. The company was able to survive for a few more years, until the start of Primo de Rivera's dictatorship in 1924, when the Railway Statute was introduced. This statute established state aid and subsidies for various railway companies to enhance their outdated and obsolete network and rolling stock. MZA utilized this aid to enhance its network and complete various construction works, including the Barcelona terminus station which was finished in 1929. Other stations from this time period that are notable include Portbou, which was also inaugurated in 1929, and Aranjuez, which was built between 1922 and 1929. The company experienced its best results in its history during the 1920s, thanks to state aid and the company's modernization plan. The company rapidly recovered and grew during this time, but it ended in 1930–1931. Following the Crash of 1929 and the refusal of new Republican governments to recognize the validity of the Railway Statute of 1924, the company's accounts declined along with the overall economic crisis. The question of state aid had reached the point where the state maintained the railways but had no say in their management.[27]

The issue of salaries was under control during the dictatorship, but the new Republic legislation caused an increase in low wages. This complicated the company's survival further. The economic results of 1935 were catastrophic, and the company soon realized that this situation could not be sustained. The nationalization of railways was a consistent topic of discussion, but political instability within the republican governments hindered any effective actions. As a result, the MZA Company persisted with its complex existence.[28]

Civil War and integration in RENFE

The Spanish Civil War outbreak also left a mark on the history of this company, as it did in many other situations. The war split the company's assets, facilities, and fleet in two, as the management was situated in Madrid. The leaders and directors located in the Republican zone had to hastily evacuate to the rebel zone due to severe pressure from the militia and workers' committees. Starting on July 18, 1936, the workers' and railwaymen's committees became the real authorities in control of the company. The war situation prompted the Republican government to nationalize all railways within its zone in order to guarantee control, although in practice they were collectivized by committees of workers and railwaymen. Thus, on August 3, 1936, the MZA Company was dissolved within the Republican zone, merging instead with the Red Nacional de Ferrocarriles (not to be confused with the later Red Nacional de los Ferrocarriles Españoles or RENFE). However, the company continued to operate within the Francoist zone while members of the prior management who had fled to the rebel zone attempted to restore the company with available resources. Despite being the legal owners and having reconstructed the organization, the Francoist military authorities would direct and administer everything related to the railways because they were crucial for the war.[29]

After the war, the company's facilities, railway network, and rolling stock suffered the consequences of the country's devastation. Despite their efforts to return to pre-war conditions, the railway companies' economic situation was dire, and they struggled to stay afloat. In the aftermath of the war, the Francoist government assumed control of major corporations without impinging on their autonomy, albeit briefly. In early 1941, RENFE was established, leading to the assimilation of the former MZA on July 1 of that year and the cessation of its operations.[29]

Legacy of MZA

Although the company officially ceased to exist in 1941 upon its integration into RENFE, this did not result in the complete elimination of all the traces it left behind. In many small yet significant details, the legacy of MZA continues to exist, as evidenced in places such as the train stations in Murcia and Cartagena. Even at Atocha station in Madrid, one can spot the inscription "Madrid-Zaragoza-Alicante" on the upper part of the walls, a distant reminder of the company's period of glory. Alternatively, some stations have preserved their original design and functionality from the time of MZA, including Aranjuez station, Barcelona-Término, and Portbou. Still other stations have preserved their design but have lost their railway function, as in the case of Plaza de Armas station in Seville.

And it is that in numerous (and sometimes unnoticed) details has remained the brand or the acronym of MZA, as is the case of the stations of Murcia or Cartagena. At Atocha station in Madrid, the legend Madrid-Zaragoza-Alicante can still be seen on the upper part of the sides, a distant memory of its period of splendor under the company. On the other hand, many stations maintain their original structure and use from the time of MZA, citing cases such as Aranjuez station, Barcelona-Término or Portbou, while other stations have maintained their structure, but have lost their railway use, as in the case of Plaza de Armas station in Seville.

Financial results

The table below displays the passengers and goods transported by MZA from 1865 to 1935. Additionally, the third column shows the percentage of operational results based on the earned income.

| Year | Travelers transported (passengers) | Merchandise transported (tons) | Operating income on revenues |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1865 | 1571700 | 554700 | |

| 1875 | 1853100 | 895100 | |

| 1882 | 2380900 | 1884700 | |

| 1888 | 2629000 | 1955500 | |

| 1894 | 2574700 | 2119200 | |

| 1902 | 10339600 | 5336700 | |

| 1907 | 12697600 | 6495900 | |

| 1917 | 18079500 | 10063400 | |

| 1921 | 26007800 | 8389200[30] | |

| 1928 | 29048800 | 12206900 | |

| 1935 | 26241800 | 8754700 |

This table shows the income,[31] expenses and operating[32] results of the company's accounts between 1861 and 1935. The final results[33] were be obtained by subtracting from the last column the liabilities (basically, the financial burden of paying the bondholders), which were always more than 75% of the operating result.

| Year | Operating income | Operating expenses | Surplus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1861 | 17322700 pts. | 7948200 pts. | |

| 1866 | 22430500 pts. | 10737400 pts. | |

| 1871 | 26997000 pts. | 9633000 pts.[34] | |

| 1876 | 37130100 pts. | 13828000 pts. | |

| 1881 | 50597300 pts.[34] | 20248800 pts. | |

| 1886 | 52676100 pts. | 21510000 pts. | |

| 1894 | 57966400 pts. | 20788100 pts. | |

| 1902 | 94768500 pts. | 38230600 pts. | |

| 1907 | 110726400 pts. | 50448600 pts. | |

| 1917 | 151328000 pts. | 82476000 pts. | |

| 1921 | 250828000 pts.[30] | 210467700 pts. | |

| 1928 | 301285300 pts. | 216765500 pts.[30] | |

| 1935 | 265578100 pts. | 221144100 pts. |

This table shows how the state supported railway companies by giving capital contributions as per the Decree-Law of July 12, 1924 or the Railway Statute of 1924. These contributions were given from 1926 to 1931 until the Republican governments withdrew the aid by denying the validity of this measure.

| Year | State capital contributions |

| 1926 | 29100000 pts. |

| 1927 | 82400000 pts. |

| 1928 | 81400000 pts. |

| 1929 | 109500000 pts. |

| 1930 | 83400000 pts. |

| 1931 | 6700000 pts. |

Owned railroad lines

Chronology of constructed lines

First sections to start operating

| Concession | Date | Section | Length (km) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Madrid-Almansa-Alicante | November 17, 1857 | Albacete-Almansa | 79,5 |

| . | March 15, 1858 | Almansa-Alicante | 96,5 |

| Madrid-Zaragoza | May 3, 1859 | Madrid-Guadalajara | 56,8 |

| . | October 5, 1860 | Guadalajara-Jadraque | 43,3 |

| . | October 1, 1861 | Zaragoza-Casetas | 13,1 |

| . | July 2, 1862 | Jadraque-Medinaceli | 61,7 |

| . | February 4, 1863 | Medinaceli-Alhama | 53,3 |

| . | May 25, 1863 | Alhama-Grisén | 96,2 |

| . | August 10, 1864 | Grisén-Casetas | 13,1 |

| . | October 1, 1864 | Casetas-Zaragoza (Campo Sepulcro) | 13,0 |

| Alcázar-Ciudad Real | July 1, 1860 | Alcázar-Manzanares | 49,2 |

| . | October 1, 1860 | Manzanares-Daimiel | 21,4 |

| . | January 21, 1861 | Daimiel-Almagro | 21,3 |

| . | March 14, 1861 | Almagro-Ciudad Real | 22,2 |

| Albacete-Cartagena | February 1, 1863 | Murcia-Cartagena | 65,1 |

| . | January 18, 1864 | Chinchilla-Hellin | 49,7 |

| . | October 8, 1864 | Cieza-Murcia | 49,3 |

| . | October 8, 1864 | Hellin-Agramón | 19,6 |

| . | March 9, 1865 | Albacete-Chinchilla | 19,1 |

| . | March 27, 1865 | Cieza-Calasparra | 24,9 |

| . | April 27, 1865 | Agramón-Calasparra | 17,8 |

| . | May 2, 1891 | Cartagena-Muelles del Levante | 0,7 |

| . | May 2, 1892 | Costa Levante-Puerto Cartagena | 0,7 |

Lines under operation

| Line | Length | Acquisition | Start-up company | Inauguration | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madrid - Almansa - Alicante | 176 km | 1856 | 1861 | Built by MZA | |

| Madrid - Zaragoza | 350,5 km | 1856 | 1865 | Built by MZA | |

| Castillejo - Toledo | 26,2 km | 1858 | Compañía del Ferrocarril de Castillejo a Toledo | 1858 | |

| Alcázar de San Juan - Ciudad Real | 134 km | 1859 | 1861 | Built by MZA | |

| Albacete - Cartagena | 245,5 km | 1863 | 1865 | Built by MZA | |

| Manzanares - Córdoba | 1860 | Built by MZA | |||

| Córdoba - Seville | 132 km | 1859 | Compañía del Ferrocarril de Córdoba a Sevilla | 1875 | |

| Seville - Huelva | 111 km | 1877 | Compañía del Ferrocarril de Sevilla a Huelva | 1880 | MZA only acquired the rights to the line and had to undertake its construction. |

| Ciudad Real - Badajoz | 324 km | 1866 | Compañía de los Caminos de Hierro de Ciudad Real a Badajoz | 1880 | |

| Almorchón - Belmez | 63,7 km | 1868 | Compañía de los Caminos de Hierro de Ciudad Real a Badajoz | 1880 | |

| Madrid - Ciudad Real | 170,3 km | 1879 | Compañía de los Caminos de Hierro de Ciudad Real a Badajoz | 1880 | |

| Mérida - Seville | 1880 | Compañía del Ferrocarril de Mérida a Sevilla | 1885 | MZA only acquired the rights to the line and had to undertake its construction. | |

| Aranjuez - Cuenca | 1880 | 1885 | MZA only acquired the rights to the line and had to undertake its construction. | ||

| Ariza - Valladolid | 254 km | 1892 | Compañía del Ferrocarril del Duero | 1895 | MZA only acquired the rights to the line and had to undertake its construction. |

| Barcelona - Granollers - Empalme | 1898 | Compañía de los ferrocarriles de Tarragona a Barcelona y Francia (TBF) | 1861 | Built by Camino de Hierro del Norte. | |

| Barcelona - Mataró - Empalme | 1898 | TBF | 1848 | Built by Camino de Hierro de Barcelona a Mataró. | |

| Empalme - Girona | 1898 | TBF | 1862 | Built by Caminos de Hierro de Barcelona a Gerona. | |

| Girona - Portbou | 1878 | TBF (Built by the company) | 1898 | ||

| Barcelona - Martorell - Tarragona | TBF | 1898 | |||

| Valls - Villanueva - Barcelona | TBF | 1898 | |||

| Roda de Bará - Reus - Caspe | 1894 | Compañía de los Ferrocarriles Directos de Madrid y Zaragoza a Barcelona and TBF (Built by the company) | 1898 |

MZA motor pool

Steam locomotives

| Type | Procedure | MZA (I) No. | MZA (II) No. | Renfe No. | Manufacturer | Factory No. | Year | Weight (t) | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 120 | MA | 1 | . | . | Stothert, Slaughter & Co, Bristol | ? | 1851 | 19,0 | . |

| 111 T | MA | 2 to 8 | . | . | Stothert, Slaughter & Co, Bristol | ? | 1852 | 17,0 | . |

| 120 T | MA | 9 a 10 | . | . | Stothert, Slaughter & Co, Bristol | ? | 1855 | 17,0 | . |

| 120 | MA | 11 to 16 | . | . | Stothert, Slaughter & Co, Bristol | ? | 1850 | 19,0 | . |

| 120 | MA | 17 to 20 | . | . | Saint-Léonard, Liège | 49-52 | 1848 | 19,0 | . |

| 021 | MA/CT | 41 to 44 | . | . | Stothert, Slaughter & Co, Bristol | ? | 1858 | 26,0 | . |

| 120 | . | 119 to 123 | 45 to 49 | . | Kitson, Leeds | 655-659 | 1858 | 29,5 | . |

| 120 | . | 124 to 128 | 50 to 54 | . | Kitson, Leeds | 665-669 | 1859 | 29,5 | . |

| 120 | . | 139 to 143 | 55 to 59 | . | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 1186-1190 | 1861 | 27,9 | . |

| 120 | . | 144 to 146 | 60 to 62 | . | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 1212-1214 | 1861 | 27,9 | . |

| 120 | . | 129 to 138 | 63 to 72 | 120-2011 | Schneider & Cie., Le Creusot | 410-419 | 1858 | 24,9 | . |

| 120 | . | . | 73 to 82 | . | Schneider & Cie., Le Creusot | 641-650 | 1861 | 24,9 | . |

| 120 | . | . | 83 to 88 | . | Schneider & Cie., Le Creusot | 663-668 | 1862 | 24,9 | . |

| 120 | . | . | 89 to 107 | 120-2012 to 2014 | Charles Evrard, Brussels | 18-36 | 1861 | 24,9 | . |

| 120 | . | . | 108 to 113 | 120-2015 | Charles Evrard, Brussels | 41, 43-47 | 1861 | 24,9 | 109-111 and 113 sold to Cordoba-Malaga (1863) |

| 120 | . | . | 114 to 118 | 120-2016 | Charles Evrard, Brussels | 51-55 | 1861 | 24,9 | . |

| 120 | . | . | 119 to 128 | 120-2017 | Ernest Goüin, París | 618-627 | 1863 | 24,9 | . |

| 120 | CS | . | 129 to 130 | . | Stephenson, Newcastle | 1035-1036 | 1857 | ? | . |

| 120 | CS | . | 131 to 142 | . | Schneider & Cie., Le Creusot | 321-332 | 1857 | 27,6 | . |

| 120 | MS | . | 143 to 148 | 120-2071 to 2072 | John Cockerill, Seraing | 995-1000 | 1879 | 29,6 | . |

| 120 | TBF | . | 149-150 | 120-2121 to 2122 | MTM, Barcelona | 9-10 | 1895 | 40,3 | . |

| 120 | TBF | . | 151-154 | 120-2101 to 2103 | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 3388-3391 | 1887 | 34,9 | . |

| 120 | TBF | . | 155-158 | 120-2104 to 2106 | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 3415-3418 | 1887 | 34,9 | . |

| 120 | TBF | . | 159 to 162 | 120-2107 to 2109 | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 3506-3509 | 1889 | 34,9 | . |

| 120 | TBF | . | 163 to 166 | 120-2110 to 2111 | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 3637-3640 | 1889 | 34,9 | . |

| 120 | TBF | . | 167 | . | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 771 | 1854 | 28,0 | . |

| 120 | TBF | . | 168 | 030-2112 | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 774 | 1854 | 28,0 | Rebuilt at 120 T about 1913 |

| 120 | TBF | . | 169 to 172 | . | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 1401-1404 | 1863 | 26,8 | . |

| 120 | TBF | . | 173 | . | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 1419 | 1863 | 26,8 | . |

| 120 | TBF | . | 174 | . | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 1424 | 1863 | 26,8 | . |

| 120 | TBF | . | 175 | . | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 1466 | 1863 | 26,8 | . |

| 120 T | TBF | . | 176 to 181 | 120-0201 to 0204 | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 2708-2713 | 1877 | 41,5 | . |

| 120 | TBF | . | 182 to 184 | . | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 1491-1492, 1494 | 1864 | 30,1 | . |

| 021 | TBF | . | 185 to 188 | . | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 1229-1232 | 1861 | 31,7 | . |

| 021 | TBF | . | 189 to 196 | 021-2011 to 2012 | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 2684-2691 | 1879 | 29,1 | . |

| 021 | TBF | . | 197 to 200 | . | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 2863-2866 | 1879 | 29,1 | . |

| 030 | . | . | 201 to 210 | 030-2261 to 2270 | Schneider & Cie., Le Creusot | 560-569 | 1860 | 30,3 | . |

| 030 | . | . | 211 to 221 | 030-2271 to 2281 | Schneider & Cie., Le Creusot | 594-604 | 1860 | 30,3 | . |

| 030 | . | . | 222 to 236 | 030-2282 to 2294 | Schneider & Cie., Le Creusot | 702-716 | 1862 | 30,3 | . |

| 030 | . | . | 237 to 238 | 030-2295 to 2296 | Graffenstaden | 192-193 | 1862 | 27,9 | . |

| 030 | . | . | 239 to 240 | 030-2297 to 2298 | Graffenstaden | 299-300 | 1864 | 27,9 | . |

| 030 | . | . | 241 to 245 | 030-2299 to 2303 | Graffenstaden | 196-200 | 1862 | 27,9 | . |

| 030 | . | 79 | 246 | 030-2013 | E.B. Wilson & Co., Leeds | 607 | 1857 | 24,7 | . |

| 030 | . | 80 | 247 | . | E.B. Wilson & Co., Leeds | 608 | 1857 | 24,7 | . |

| 030 | . | 86 to 98 | 248 to 265 | 030-2014 to 2027 | E.B. Wilson & Co., Leeds | 609-626 | 1857 | 24,7 | . |

| 030 | . | 99 to 103 | 266 to 270 | 030-2028 to 2031 | Kitson, Leeds | 599-603 | 1857 | 24,7 | . |

| 030 | . | 104 to 108 | 271 to 275 | 030-2032 | Kitson, Leeds | 609-613 | 1857 | 24,7 | . |

| 030 | . | 109 to 113 | 276 to 280 | 030-2033 to 2036 | Kitson, Leeds | 625-629 | 1857 | 24,7 | . |

| 030 | . | 114 to 118 | 281 to 285 | 030-2037 to 2040 | Kitson, Leeds | 645-649 | 1857 | 24,7 | . |

| 030 | . | 49 to 58 | 286 to 295 | 030-2041 to 2047 | J.F. Cail & Cie., París | 624-633 | 1857 | 24,7 | . |

| 030 | . | 59 to 68 | 296 to 305 | 030-2048 to 2053 | J.F. Cail & Cie., París | 634-643 | 1858 | 24,7 | . |

| 030 | . | 69 to 78 | 306 to 315 | 030-2054 to 2059 | J.F. Cail & Cie., París | 661-670 | 1858 | 24,7 | . |

| 030 | . | 151 | 316 | . | John Cockerill, Seraing | 511 | 1860 | 24,7 | . |

| 030 | MA | 11 to 12 | 317 to 318 | . | Stothert, Slaugther and Company, Bristol | ? | 1856 | ? | . |

| 030 | MA | 43 to 48 | 319 to 324 | . | Slaugther-Grünning, Bristol | 343-348 | 1858 | ? | . |

| 030 | TBF | . | 317 to 320 (II) | 030-2116 to 2119 | Avonside Engine Company, Bristol | 750-753 | 1868 | 39,4 | . |

| 030 | TBF | . | 321 to 324 (II) | 030-2120 to 2123 | Avonside Engine Company, Bristol | 843-846 | 1871 | 39,4 | . |

| 030 | . | . | 325 to 326 | 030-2304 to 2305 | Graffenstaden | 289-290 | 1862 | 27,9 | . |

| 030 | . | . | 327 to 330 | . | Graffenstaden | 291-294 | 1863 | 27,9 | Sold to Portugal |

| 030 | . | . | 331 to 334 | 030-2306 to 2309 | Graffenstaden | 325-328 | 1864 | 27,9 | . |

| 030 | . | . | 335 to 342 | 030-2310 to 2317 | Schneider & Cie., Le Creusot | 779-786 | 1863 | 32,3 | . |

| 030 | . | . | 343 to 359 | 030-2318 to 2334 | Schneider & Cie., Le Creusot | 801-816 | 1863 | 32,3 | . |

| 030 | . | . | 360 to 364 | 030-2335 to 2339 | Schneider & Cie., Le Creusot | 830-834 | 1865 | 32,3 | Sold to the ZPB (1872);

They returned to MZA in 1880. |

| 030 | . | . | 365 a 369 | . | Schneider & Cie., Le Creusot | 835-839 | 1865 | 32,3 | Transferred to Cordoba-Malaga (1865). |

| 030 | CS | . | 370 to 373 | . | Haswell, Vienna | 689-692 | 1863 | 27,9 | Ceded to Norte |

| 030 | . | . | 374 to 387 | 030-2340 to 2353 | SACM, Graffenstaden | 2810-2823 | 1879 | 32,0 | . |

| 030 | . | . | 388 to 399 | 030-2354 to 2365 | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 2822-2833 | 1879 | 32,0 | . |

| 030 | CRB | . | 401 to 406 | 030-2209 to 2214 | Fives-Lille | 2232-2237 | 1878 | 34,8 | . |

| 030 | CRB | . | 407 to 414 | 030-2215 to 2222 | Fives-Lille | 2271-2278 | 1880 | 34,8 | . |

| 030 | . | . | 415 to 434 | 030-2231 to 2250 | Franco-Belge, La Croyère | 427-446 | 1883 | 36,4 | . |

| 030 | AC | . | 435 to 441 | 030-2479 to 2485 | Hartmann, Chemnitz | 1244-1250 | 1883 | 36,1 | . |

| 030 | AC | . | 442 to 446 | 030-2388 to 2392 | Dübs, Glasgow | 1555-1559 | 1881 | 38,2 | . |

| 030 | TBF | . | 447 to 448 | . | André Koechlin & Cie., Mulhouse | ? | 1870 | ? | . |

| 130 | TBF | . | 449 to 451 | . | Rogers Locomotive and Machine Works | 3462-3464 | 1883 | 39,0 | . |

| 130 | TBF | . | 452 | . | Rogers Locomotive and Machine Works | 2707 | 1880 | 38,1 | . |

| 030 | TBF | . | 453 | . | Rogers Locomotive and Machine Works | 2689 | 1880 | 38,1 | . |

| 030 | TBF | . | 454 to 465 | 030-2577 to 2588 | Hartmann, Chemnitz | 1204-1215 | 1882 | 34,4 | . |

| 030 | TBF | . | 466 to 477 | 030-2589 to 2600 | Hartmann, Chemnitz | 1280-1291 | 1883 | 34,4 | . |

| 030 | TBF | . | 478 to 481 | 030-2601 to 2604 | Hartmann, Chemnitz | 1473-1476 | 1886 | 34,4 | . |

| 030 | TBF | . | 482 to 485 | 030-2605 to 2608 | Hartmann, Chemnitz | 1683-1686 | 1890 | 34,4 | . |

| 040 | CRB | . | 501 to 516 | 040-2031 to 2036 | J.F. Cail & Cie., París | 1268-1273 | 1863 | 39,0 | . |

| 040 | CRB | . | 507 to 511 | 040-2037 to 2041 | J.F. Cail & Cie., París | 1276-1281 | 1863 | 39,0 | . |

| 040 | CRB | . | 512 to 516 | . | J.F. Cail & Cie., París | 1281-1285 | 1864 | 39,0 | Sold to Andaluces |

| 040 | CRB | . | 517 to 522 | . | J.F. Cail & Cie., París | 1374-1379 | 1865 | 39,0 | Sold to Andaluces |

| 040 | CRB | . | 523 to 526 | . | J.F. Cail & Cie., París | 1380-1383 | 1865 | 39,0 | Sold to ZPB |

| 040 | CRB | . | 527 to 536 | 040-2042 to 2052 | Schneider & Cie., Le Creusot | 907-916 | 1865 | 39,0 | . |

| 040 | MS | . | 537 to 546 | 040-2061 to 2072 | John Cockerill, Seraing | 1001-1010 | 1878 | 39,9 | . |

| 040 | . | . | 547 to 561 | 040-2271 to 2285 | MTM, Barcelona | 18-32 | 1900 | 43,0 | . |

| 040 | TBF | . | 562 to 566 | 040-2011 to 2015 | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 2779-2783 | 1879 | 42,8 | . |

| 040 | TBF | . | 567 | . | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 2784 | 1879 | 42,8 | . |

| 040 | TBF | . | 568 to 571 | 040-2016 to 2019 | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 2851-2854 | 1879 | 42,8 | . |

| 040 | TBF | . | 572 to 575 | 040-2020 to 2023 | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 2896-2899 | 1879 | 42,8 | . |

| 040 | TBF | . | 576 to 583 | 040-2301 to 2308 | Sharp-Stewart, Manchester | 3520-3527 | 1889 | 44,7 | . |

| 020 T | . | . | 601 to 610 | 020-0231 to 0240 | Couillet | 786-795 | 1885 | 19,0 | . |

| 020 T | TBF | . | 611 | 020-0211 | Anjubault, París | 103 | 1864 | 22,0 | . |

| 020 T | TBF | . | 612 | 020-0212 | Anjubault, París | 105 | 1865 | 22,0 | . |

| 030 ST | TBF | . | 613 | . | (English?) | ? | ? | ? | . |

| 232 T | . | . | 620 to 631 | 232-0201 to 0212 | J.A. Maffeï, Munich | 2339-2350 | 1903 | 58,9 | . |

| 232 T | . | . | 632 to 641 | 232-0213 to 0220 | J.A. Maffeï, Munich | 3260-3269 | 1911 | 58,9 | . |

| 230 | . | . | 651 to 665 | 230-4001 to 4015 | G. Egestorff, Hanover | 3654-3668 | 1901 | 55,5 | . |

| 230 | . | . | 666 to 680 | 230-4016 to 4030 | Henschel, Cassel | 6308-6322 | 1903 | 55,5 | . |

| 040 | . | . | 741 to 746 | 040-2401 to 2406 | Henschel, Cassel | 8363-8388 | 1907 | 51,0 | . |

| 231 | . | . | 901 to 911 | 231-2011 to 2021 | ALCO, Brooks | 61772-61782 | 1920 | 76,6 | . |

| 231 | . | . | 912 | . | ALCO, Brooks | 61783 | 1920 | 76,6 | . |

| 231 | . | . | 913 to 915 | 231-2022 to 2024 | ALCO, Brooks | 61784-61786 | 1920 | 76,6 | . |

| 240 | . | . | 1301 to 1307 | 240-4051 to 4057 | Hanomag, Hanover | 6484-6490 | 1914 | 79,0 | . |

| 240 | . | . | 1308 | 240-4058 | Hanomag, Hanover | 6991 | 1920 | 79,0 | . |

| 240 | . | . | 1536 to 1565 | 240-2396 to 2425 | MTM, Barcelona | 438-467 | 1930 | 82,5 | . |

| 242 T | . | . | 1601 to 1625 | 242-0231 to 0255 | MTM, Barcelona | 154-178 | 1924 | 92,5 | . |

| 242 T | . | . | 1626 to 1650 | 242-0256 to 0280 | MTM, Barcelona | 220-244 | 1926 | 86,7 | . |

| 242 T | . | . | 1651 to 1660 | 242-0281 to 0290 | MTM, Barcelona | 325-334 | 1927 | 87,4 | . |

| 241 | . | . | 1701 to 1725 | 241-2001 to 2025 | MTM, Barcelona | 179-203 | 1925 | 92,6 | . |

| 241 | . | . | 1726 to 1765 | 241-2026 to 2065 | MTM, Barcelona | 284-323 | 1927 | 93,2 | . |

| 241 | . | . | 1766 to 1775 | 241-2066 to 2075 | MTM, Barcelona | 380-389 | 1929 | 94,6 | . |

| 241 | . | . | 1776 to 1785 | 241-2076 to 2085 | MTM, Barcelona | 428-437 | 1930 | 94,5 | . |

| 241 | . | . | 1786 to 1795 | 241-2086 to 2095 | MTM, Barcelona | 468-477 | 1931 | 96,5 | . |

| 241 | . | . | 1801 to 1810 | 241-2101 to 2110 | MTM, Barcelona | 499-508 | 1939 | 107,5 | . |

| 240 | . | . | 2401 to 2425 | 240-2481 to 2505 | MTM, Barcelona | 519-543 | 1942 | 96,6 | . |

| 240 | . | . | 2426 to 2445 | 240-2506 to 2525 | Euskalduna, Bilbao | 240-259 | 1943 | 96,6 | . |

| 240 | . | . | 2446 to 2460 | 240-2526 to 2540 | MTM, Barcelona | 559-573 | 1943 | 96,6 | . |

| 240 | . | . | 2466 to 2475 | 240-2451 to 2550 | MTM, Barcelona | 549-558 | 1943 | 96,6 | . |

| 240 | . | . | 2481 to 2499 | 240-2551 to 2569 | Babcock & Wilcox, Bilbao | 552-570 | 1951 | 96,6 | . |

| 241 | . | . | 2701 to 2722 | 240-2201 to 2222 | MTM, Barcelona | 594-615 | 1944 | 120,0 | . |

Thermal railcars

| Type | MZA No. | Renfe No. | Manufacturer | Factory No. | Year | Engine | Power | Weight | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA GM | WM 101 to 104 | 9151 to 9154 | Carde y Escoriaza, Zaragoza | ? | 1937 | Renault | 110 cv | t? | Renault license, type "ZO". |

| BoBo DE | WE 201 to 204 | 9200 to 9202 | MTM, Barcelona | ? | 1936 | Burmeister & Wain, Copenhague, type 613,5 VL 22 | 250 cv | t? | . |

| BoBo DM | WM 226 to 227 | 9204 to 9205 | MMC, Zaragoza | 59-60 | 1936 | Renault type 517 | 265 cv | t? | Renault license. Type "ABJ 2". |

| BoBo DM | WM 228 to 231 | 9300 to 9303 | MMC, Zaragoza | ? | 1936 | Renault type 517 | 300 cv | t? | Renault license. Type "ABJ 2". |

| BoBo DE | WE 401 to 404 | 9403 to 9405 | CAF, Beasain | ? | 1935 | Maybach, Friedrichshafen, type GO.5 | 410 cv | t? | . |

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e Wais San Martín (1974, p. 177)

- ^ Lentisco (2005, p. 235)

- ^ a b Lentisco (2005, p. 181)

- ^ a b Lentisco (2005, p. 182)

- ^ Wais San Martín (1974, p. 176)

- ^ a b c Wais San Martín (1974, p. 183)

- ^ Wais San Martín (1974, p. 180)

- ^ a b Wais San Martín (1974, p. 184)

- ^ Wais San Martín (1974, p. 182)

- ^ Wais San Martín (1974, p. 185)

- ^ Wais San Martín (1974, p. 187)

- ^ Wais San Martín (1974, p. 191)

- ^ Wais San Martín (1974, p. 192)

- ^ Wais San Martín (1974, p. 195)

- ^ Wais San Martín (1974, p. 199)

- ^ a b Wais San Martín (1974, p. 205)

- ^ Wais San Martín (1974, p. 206)

- ^ a b Wais San Martín (1974, p. 210)

- ^ Wais San Martín (1974, p. 208)

- ^ a b Wais San Martín (1974, p. 209)

- ^ Wais San Martín (1974, p. 212)

- ^ Wais San Martín (1974, p. 223)

- ^ a b Wais San Martín (1974, p. 224)

- ^ Wais San Martín (1974, p. 225)

- ^ a b Lentisco (2005, p. 235)

- ^ a b Wais San Martín (1974, p. 613)

- ^ Wais San Martín (1974, p. 623)

- ^ Lentisco (2005, p. 260)

- ^ a b Lentisco (2005, p. 261)

- ^ a b c Álvarez de Castrillón (1978, p. 447)

- ^ "FerroEstad - Compañia de los Ferrocarriles de Madrid a Zaragoza y Alicante". www.docutren.com. Retrieved 2023-10-17.

- ^ "FerroEstad - Compañia de los Ferrocarriles de Madrid a Zaragoza y Alicante". www.docutren.com. Retrieved 2023-10-17.

- ^ "FerroEstad - Compañia de los Ferrocarriles de Madrid a Zaragoza y Alicante". www.docutren.com. Retrieved 2023-10-17.

- ^ a b Álvarez de Castrillón (1978, p. 412)

Bibliography

- Álvarez de Castrillón, Rafael Anes (1978). Ferrocarriles en España 1844-1943, Tomo 2: Economía y los ferrocarriles (in Spanish). Madrid: Servicio de Publicaciones del Banco de España.

- Artola, Miguel (1978). Ferrocarriles en España 1844-1943, Tomo 1: El estado y los ferrocarriles (in Spanish). Madrid: Servicio de Publicaciones del Banco de España.

- Fernández Sanz, Fernando; Reder, Gustavo (1995). Historia de la tracción vapor en España, Tomo 1, Locomotoras de MZA (in Spanish). Madrid. ISBN 84-920492-0-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - García de Cortázar, Fernando (2005). Atlas Historia de España (in Spanish). Barcelona: Círculo de Lectores. p. 555. ISBN 84-672-1436-8.

- Lentisco, David (2005). Cuando el hierro se hace camino, Historia del Ferrocarril en España (in Spanish). Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

- Maristany Gibert, Eduardo (1897). Puente sobre el río Martín en el kilómetro 6,373 de la línea de Val de Zafán a Gargallo (in Spanish). Vol. II. Revista de Obras Públicas. pp. 413–418.

- Wais San Martín, Francisco (1974). Historia de los Ferrocarriles Españoles (in Spanish). Madrid: Editorial Española.