Macro-Pama–Nyungan languages

| Macro-Pama–Nyungan | |

|---|---|

| (controversial) | |

| Geographic distribution | northern Australia |

| Linguistic classification | Proposed language family |

| Subdivisions | |

| Language codes | |

| Glottolog | None |

Pama–Nyungan (yellow), Garawa and Tangkic (green), and Macro-Gunwinyguan (orange) | |

Macro-Pama-Nyungan is an umbrella term used to refer to a proposed Indigenous Australian language family. It was coined by the Australian linguist Nicholas Evans in his 1996 book Archaeology and linguistics: Aboriginal Australia in global perspective, co-authored by Patrick McConvell.[1] The term arose from Evans' theory suggesting that two of the largest Indigenous Australian language families share a common origin, and should therefore be classified as a singular language family under "Macro-Pama-Nyungan".[2]

The two main families that Evans refers to are the Macro-Gunwinyguan family from Northern Australia,[3] and the most widespread Pama–Nyungan family that spans across mainland and Southern Australia.[4] The different theories regarding Australian linguistic prehistory and Australian language family evolution are widely debated, therefore Macro-Pama-Nyungan is an inconclusive language family classification that is often dissented by linguists in the Aboriginal Australian language community.[5]

The legitimacy of the Macro-Pama-Nyungan classification and supporting theories remain open to question since language reconstruction of Indigenous Australian language families is in its early stages.[5]

Term and origins

The term "Macro-Pama-Nyungan", or otherwise interchangeably referred to as 'Gunwinyguan-Tangkic-Karrwan (Garrwan)-Pama-Nyungan',[1] was first coined in the 1997 book Archaeology and linguistics: Aboriginal Australia in global perspective, by the Australian linguist Nicholas Evans, co-authored by Patrick McConvell.[2] It refers to a proposed classification of a large Indigenous Australian language family sharing a common linguistic origin that geographically spreads across the continent from Arnhem Land in Northern Australia to Southwestern Australia.[2]

Evans explores this claim of a higher-level "Macro-Pama-Nyungan" Indigenous Australian language family classification[6] in several of his works. His most notable books are The Cradle of the Pama-Nyungans: Archaeological and Linguistic Speculations, published in 1997 co-authored by Rhys Jones,[7] and The non-Pama-Nyungan languages of northern Australia: comparative studies of the continent's most linguistically complex region published in 2003 and edited by Evans.[6] In his works, Evans uses the Macro-Pama-Nyungan term to propose that the majority of Indigenous languages across Australia have a common origin and share an inheritance with a common linguistic ancestor.[6]

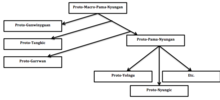

According to Evans, the Macro-Pama-Nyungan language family is made up of the Gunwinyguan languages from Arnhem Land in Northern Australia, the Tangkic languages from Mornington Island in the Wellesley Islands of Queensland, the Garrwan (or Karrwan) languages from Queensland and the Northern Territory, and the larger Pama–Nyungan language family[6] that geographically covers approximately 90% of the Australian continent.[8] The grouping of the Gunwinyguan, Tangkic and Garrwan language families from northern Australia forms the "macro" extension of Pama–Nyungan language family to form the Macro-Pama-Nyungan term.[6] The larger Pama–Nyungan family includes around 300 Aboriginal languages, mainly located across southern parts of Australia.[4]

Prior to this, the American linguist Kenneth L. Hale establishes the Pama–Nyungan language family classification in the year 1964 in his work Classification of Northern Paman Languages.[9] He concludes that the Pama–Nyungan language family is "one relatively closely interrelated family [that] had spread and proliferated over most of the continent, while approximately a dozen other families were concentrated along the North coast".[9] In the book edited by Evans, The non-Pama-Nyungan languages of northern Australia: comparative studies of the continent's most linguistically complex region, Evans refers to Hale's Pama–Nyungan classification, and claims that out of the dozen other families concentrated along Northern Australia, Gunwinyguan, Tangkic and Garrwan are three non-Pama-Nyungan language families that do in fact have a close relation to the Pama–Nyungan language family, and should therefore be classified under one large Macro-Pama Nyungan language family.[6]

Evans uses the Pama–Nyungan offshoot model from the article written by Geoffrey O'Grady, Preliminaries to a proto Nuclear Pama-Nyungan stem list[10] to propose that Pama–Nyungan is an offshoot language family sharing immediate ancestry with these three non-Pama-Nyungan subgroups.[6] Evans identifies the Garrwan language as a close sister of the Pama–Nyungan languages, due to the morphological and phonological elements found in the Garrwan language that link Pama–Nyungan languages to the stages when the Proto-Pama–Nyungan languages split from its predecessors.[6] Evans also refers to O'Grady's grouping of the Gunwinyguan and Tangkic languages with the Pama–Nyungan language group as 'nuclear Pama–Nyungan',[10] in order to make the higher-level Macro-Pama-Nyungan language family classification.[6]

Considering that the vast majority of Australian Aboriginal languages have become extinct with no living speakers and that many of the remaining Australian Aboriginal languages are also endangered to some degree,[11] many linguists acknowledge that language family classification is an inconclusive debate that needs further exploration and research since Indigenous Australian language family reconstruction is in its early stages,[5] and the legitimacy of chosen reconstruction methods is widely debated.[12]

Expansion theories

With limited reconstruction work having been done on Pama–Nyungan and non-Pama-Nyungan language families and their subgroups,[12] further study of the linguistic stratigraphy of loanwords is needed to provide a foundation for hypotheses to be made about the sociocultural and environmental prehistory of Indigenous Australia.[12]

There is considerable debate over which of the linguistic elements found across language groups are attributed to a shared inheritance from a common ancestor, and which elements are attributed to more recent contact between linguistic groups.[12] These two points form two theories surrounding the extent to which Pama–Nyungan languages are proposed to have spread across Australia,[8] leading to the ongoing classification and declassification debate over the possibility of a legitimate Macro-Pama-Nyungan language family.[14]

The first theory suggests that the size and spread of the Pama–Nyungan language family is attributed to demic diffusion resulting from climatic changes, causing people to seek refuge in inhabitable areas.[8] The timing of Pama–Nyungan language family expansion as the largest hunter-gatherer language family in the world has possible origins in the Gulf Plains region,[8] with four possible timings for demic diffusion put forth. The first is upon initial colonisation of Australia, the second as late Pleistocene, the third as early Holocene, and the fourth as after the Last Glacial Maximum.[8]

The second theory suggests that social and technological advantages and the intensification and spread of agricultural techniques facilitated the large-scale replacement of non-Pama-Nyungan languages during the mid-Holocene, originating from the Gulf Plains region.[8] Linguists Bouckaert, Bowern, and Atkinson state that "Pama-Nyungan languages were carried as a part of an expanding package of cultural innovations that probably facilitated the absorption and assimilation of existing hunter-gatherer groups",[8] acknowledging possible associations with the introduction of the dingo, new lithic technologies and social institutions.[8]

According to the Diversification of the Pama–Nyungan language family tree presented in figure 2 of The origin and expansion of Pama–Nyungan languages across Australia by Bouckaert, Bowern and Atkinson, the earliest three subgroups to break off from the Pama–Nyungan language family were the Western branch, the Southern group and the Tangkic branch.[8] These groups collectively expand across South Australia, Western Australia, the Northern Territory, Victoria, the majority of New South Wales and the Southeast Queensland coast.[8] Bouckaert, Bowern and Atkinson acknowledge the existence of patterns consistent with language group settlement along watercourses that could indicate rivers and coastline areas as possible launching points for group and language fission, however this is not supported by the migration model put forth in the same journal article.[8]

Internal classification

Due to the extinction of many Indigenous Australian languages, there is limited access to linguistic evidence. Linguists have therefore used geographic, genetic, archaeological and linguistic methods to form language family reconstructions and associations.[15] The legitimacy of these methods is questioned amongst linguists and has formed a widespread debate on the classification and declassification of certain Indigenous Australian language families and their subgroups.[12]

Whether the three non-Pama-Nyungan language families Gunwinyguan, Tangkic and Garrwan can be classified as Macro-Pama-Nyungan as proposed by Evans is inconclusive due to the legitimacy of relational strength to the Pama–Nyungan language family.[5] Evans' classification of the Gunwinyguan family is unclear due to the use of unestablished, non-traditional linguistic reconstruction methods.[5] Linguist Rebecca Green argues that the shared irregularities in verb morphology indicate that Gunwinyguan is in fact part of the Macro-Pama-Nyungan family,[16] and linguist Harvey refers to Evans' position on grammatical grounds that "these languages have been in and out of Pama-Nyungan throughout the history of classification" as justification to support the Macro-Pama-Nyungan classification.[14]

Evans proposes that the Gunwinyguan family could be a sister to the Macro-Pama-Nyungan family that contains Tangkic, Garrwan and core Pama–Nyungan. Of these three subgroups, Tangkic is considered one of the earliest formed branches of the Greater-Pama-Nyungan language family,[8] and Bowern acknowledges that some linguists suggest Tangkic has close relations to the Pama–Nyungan Yolŋu languages.[8] McConvell and Bowern mention the linguistic geography hypothesis put forward by Hale stating that the Pama–Nyungan family originates from the base of the Gulf of Carpentaria, and note that according to Evans, this places Pama–Nyungan families in close proximity to the Garrwan and Tangkic families.[12]

Opposition

The Macro-Pama-Nyungan claim is an inconclusive language family classification, yet Aboriginal Australian linguists acknowledge the possible legitimacy of the claim.[5] Due to the lack of evidence and questionable methods used to make linguistic reconstructions and associations between language families and their subgroups,[12] the Macro-Pama-Nyungan claim is widely dissented among linguists in the Aboriginal Australian language community.[citation needed]

In Historical linguistics in Australia: trees, networks and their implications, Bowern states that the Macro-Pama-Nyungan language tree model used by Evans is "based on very little evidence" due to the fact that "a single shared innovation defines each of these nodes".[5] Bouckaert, Bowern and Atkinson state that there are several non-Pama-Nyungan groups that separate and disprove the proposed relationship between the non-Pama-Nyungan Garrwan family and the Pama–Nyungan Yolŋu family that has been put forth in the Aboriginal Australian language community.[8]

Bowern argues that the Gunwinyguan family contains a number of Arnhem Land languages that are not considered to be closely related to the Pama–Nyungan language family, disputing Gunwinyguan, Tangkic and Garrwan as classifiable under Macro-Pama-Nyungan.[5] In regard to Evans' claims that Gunwinyguan could possibly be a sister to the Macro-Pama-Nyungan family, McConvell and Bowern both note that Gunwinyguan cannot be classed as both a sister to the Macro-Pama-Nyungan family and as a part of the Arnhem Land family subgroup simultaneously.[12]

References

- ^ a b Evans & McConvell 1996, pp. 385–417.

- ^ a b c Evans & McConvell 1996.

- ^ "Macro-Gunwinyguan languages", my spectroom, retrieved 22 April 2020

- ^ a b Frawley 2003.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bowern 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Evans 2003.

- ^ Evans & Jones 1997.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Bouckaert, Bowern & Atkinson 2018.

- ^ a b Hale 1964.

- ^ a b O'Grady 1979.

- ^ "Loss of Aboriginal Languages". Creative Spirits. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h McConvell & Bowern 2011.

- ^ Evans 2005.

- ^ a b Harvey 2008.

- ^ Lilley, Ian (2010), Review of Archaeology and linguistics: Aboriginal Australia in global perspective, Australian Archaeological Association

- ^ Green 2003.

Bibliography

- Bouckaert, Remco R.; Bowern, Claire; Atkinson, Quentin D. (2018). "The origin and expansion of Pama–Nyungan languages across Australia". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2 (4): 741–749. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0489-3. PMID 29531347. S2CID 4208351.

- Bowern, Claire (2010). "Historical linguistics in Australia: trees, networks and their implications". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 365 (1559): 3845–3854. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0013. PMC 2981908. PMID 21041209.

- Evans, Nicholas (2005). "Australian Languages Reconsidered: A Review of Dixon (2002)". Oceanic Linguistics. 44 (1): 242–286. doi:10.1353/ol.2005.0020. hdl:1885/31199. JSTOR 3623237. S2CID 145688642.

- Evans, Nicholas (2003). The non-Pama-Nyungan languages of northern Australia: comparative studies of the continent's most linguistically complex region. Canberra, Australia: Pacific Linguistics. ISBN 0-85883-538-X.

- Evans, Nicholas; Jones, Rhys (1997). "The cradle of the Pama-Nyungans: archaeological and linguistic speculations". Archaeology and Linguistics: Aboriginal Australia in Global Perspective. pp. 385–417, 423–453.

- Evans, Nicholas; McConvell, Patrick (1996). Archaeology and linguistics: Aboriginal Australia in global perspective. Melbourne; New York: Oxford University Press Australia. pp. 385–417. ISBN 0-19-553728-9.

- Frawley, William (2003). International encyclopedia of linguistics. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gaby, Alice (2009). "Teaching & Learning Guide for: Rebuilding Australia's Linguistic Profile – Recent Developments in Research on Australian Aboriginal Languages". Language and Linguistics Compass. 3 (5). Wiley Online Library: 1366–1373. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818X.2009.00162.x.

- Green, Rebecca (2003). "Proto Maningrida within Proto Arnhem: evidence from verbal inflectional suffixes". In Evans, Nicolas (ed.). The Non-Pama-Nyungan languages of Northern Australia: comparative studies of the continent's most linguistically complex region. Canberra, Australia: Pacific Linguistics.

- Hale, Kenneth L. (1964). "Classification of Northern Paman Languages, Cape York Peninsula, Australia; A Research Report". Oceanic Linguistics. 3 (2): 248–264. doi:10.2307/3622881. JSTOR 3622881.

- Harvey, Mark (2008). Proto Mirndi. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

- McConvell, Patrick (1990). "The Linguistic Prehistory Of Australia: Opportunities For Dialogue With Archaeology". Australian Archaeology. 31 (1): 3–27. doi:10.1080/03122417.1990.11681384.

- McConvell, Patrick; Bowern, Claire (2011). "The Prehistory of Internal Relationships of Australian Languages". Language and Linguistics Compass. 5 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818X.2010.00257.x.

- O'Grady, Geoffrey (1979). "Preliminaries to a Proto Nuclear Pama-Nyungan stem list". In Wurm, Stephen A. (ed.). Australian Linguistic Studies (Pacific Linguistic C-54). Canberra: Australian National University.