Luxembourg City

Luxembourg

| |

|---|---|

Capital city and commune | |

| Stad Lëtzebuerg | |

View of the Ville Haute, including the Fortress of Luxembourg, the Gëlle Fra and the Notre-Dame Cathedral | |

Map of Luxembourg with Luxembourg City highlighted in orange, and the canton in dark red | |

| Coordinates: 49°36′42″N 6°7′55″E / 49.61167°N 6.13194°E | |

| Country | Luxembourg |

| Canton | Luxembourg |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Lydie Polfer (DP) |

| Area | |

• Total | 51.46 km2 (19.87 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 7th of 100 |

| Highest elevation | 402 m (1,319 ft) |

| • Rank | 48th of 100 |

| Lowest elevation | 230 m (750 ft) |

| • Rank | 42nd of 100 |

| Population (2024) | |

• Total | 134,697 |

| • Rank | 1st of 100 |

| • Density | 2,600/km2 (6,800/sq mi) |

| • Rank | 2nd of 100 |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| LAU 2 | LU0000304 |

| Website | vdl.lu |

| |

| Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

Luxembourg (Luxembourgish: Lëtzebuerg; French: Luxembourg; German: Luxemburg),[pron 1] also known as Luxembourg City (Luxembourgish: Stad Lëtzebuerg or d'Stad; French: Ville de Luxembourg; German: Stadt Luxemburg or Luxemburg-Stadt),[pron 2] is the capital city of Luxembourg and the country's most populous commune. Standing at the confluence of the Alzette and Pétrusse rivers in southern Luxembourg, the city lies at the heart of Western Europe, situated 213 km (132 mi) by road from Brussels and 209 km (130 mi) from Cologne.[1] The city contains Luxembourg Castle, established by the Franks in the Early Middle Ages, around which a settlement developed.

As of 1 September 2024, Luxembourg City has a population of 135,441 inhabitants,[2] which is more than three times the population of the country's second most populous commune (Esch-sur-Alzette). The population consists of 160 nationalities. Foreigners represent 70.4% of the city's population, whilst Luxembourgers represent 29.6% of the population; the number of foreign-born residents in the city rises steadily each year.[3]

In 2024, Luxembourg was ranked by the IMF as having the highest GDP per capita in the world at $140,310 (PPP),[4] with the city having developed into a banking and administrative centre. In the 2019 Mercer worldwide survey of 231 cities, Luxembourg was placed first for personal safety, while it was ranked 18th for quality of living.[5]

Luxembourg is one of the de facto capitals of the European Union (alongside Brussels, Frankfurt and Strasbourg), as it is the seat of several institutions, agencies and bodies, including the Court of Justice of the European Union, the European Court of Auditors, the Secretariat of the European Parliament, the European Public Prosecutor's Office, the European Investment Bank, the European Investment Fund, the European Stability Mechanism, Eurostat, as well as other European Commission departments and services.[6] The Council of the European Union meets in the city for three months annually.[6]

History

In the Roman era, a fortified tower guarded the crossing of two Roman roads that met at the site of Luxembourg city. Through an exchange treaty with the abbey of Saint Maximin in Trier in 963, Siegfried I of the Ardennes, a close relative of King Louis II of France and Emperor Otto the Great, acquired the feudal lands of Luxembourg. Siegfried built his castle, named Lucilinburhuc ("small castle"), on the Bock Fiels ("rock"), mentioned for the first time in the aforementioned exchange treaty.

In 987, Archbishop Egbert of Trier consecrated five altars in the Church of the Redemption (today St. Michael's Church). At a Roman road intersection near the church, a marketplace appeared around which the city developed.

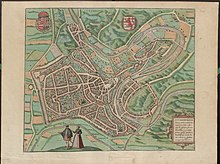

The city, because of its location and natural geography, has through history been a place of strategic military significance. The first fortifications were built as early as the 10th century. By the end of the 12th century, as the city expanded westward around the new St. Nicholas Church (today the Cathedral of Notre Dame), new walls were built that included an area of 5 hectares (12 acres). In about 1340, under the reign of John the Blind, new fortifications were built that stood until 1867.

In 1443, the Burgundians under Philip the Good conquered Luxembourg. Luxembourg became part of the Burgundian, and later Spanish and Austrian empires (See Spanish Netherlands and Spanish Road) and under those Habsburg administrations Luxembourg Castle was repeatedly strengthened so that by the 16th century, Luxembourg itself was one of the strongest fortifications in Europe. Subsequently, the Burgundians, the Spanish, the French, the Spanish again, the Austrians, the French again, and the Prussians conquered Luxembourg.[citation needed]

In the 17th century, the first casemates were built; initially, Spain built 23 km (14 mi) of tunnels, starting in 1644.[7] These were then enlarged under French rule by Marshal Vauban, and augmented again under Austrian rule in the 1730s and 1740s.

During the French Revolutionary Wars, the city was occupied by France twice: once, briefly, in 1792–93, and, later, after a seven-month siege.[8] Luxembourg held out for so long under the French siege that French politician and military engineer Lazare Carnot called Luxembourg "the best fortress in the world, except Gibraltar", giving rise to the city's nickname: the 'Gibraltar of the North'.[8]

Nonetheless, the Austrian garrison eventually surrendered, and as a consequence, Luxembourg was annexed by the French Republic, becoming part of the département of Forêts, with Luxembourg City as its préfecture. Under the 1815 Treaty of Paris, which ended the Napoleonic Wars, Luxembourg City was placed under Prussian military control as a part of the German Confederation, although sovereignty passed to the House of Orange-Nassau, in personal union with the United Kingdom of the Netherlands.

After the Luxembourg Crisis, the 1867 Treaty of London required Luxembourg to dismantle the fortifications in Luxembourg City. Their demolition took sixteen years, cost 1.5 million gold francs, and required the destruction of over 24 km (15 mi) of underground defences and 4 hectares (9.9 acres) of casemates, batteries, barracks, etc.[9] Furthermore, the Prussian garrison was to be withdrawn.[10]

When, in 1890, Grand Duke William III died without any male heirs, the Grand Duchy passed out of Dutch hands, and into an independent line under Grand Duke Adolphe. Thus, Luxembourg, which had hitherto been independent in theory only, became a truly independent country, and Luxembourg City regained some of the importance that it had lost in 1867 by becoming the capital of a fully independent state.

Despite Luxembourg's best efforts to remain neutral in the First World War, it was occupied by Germany on 2 August 1914. On 30 August, Helmuth von Moltke moved his headquarters to Luxembourg City, closer to his armies in France in preparation for a swift victory. However, the victory never came, and Luxembourg would play host to the German high command for another four years. At the end of the occupation, Luxembourg City was the scene of an attempted communist revolution; on 9 November 1918, communists declared a socialist republic, but it lasted only a few hours.[11]

In 1921, the city limits were greatly expanded. The communes of Eich, Hamm, Hollerich, and Rollingergrund were incorporated into Luxembourg City, making the city the largest commune in the country (a position that it would hold until 1978).

In 1940, Germany occupied Luxembourg again. The Nazis were not prepared to allow Luxembourgers self-government, and gradually integrated Luxembourg into the Third Reich by informally attaching the country administratively to a neighbouring German province. Under the occupation, the capital city's streets all received new, German names, which was announced on 4 October 1940.[12] The Avenue de la Liberté for example, a major road leading to the railway station, was renamed "Adolf-Hitlerstraße".[12] Luxembourg City was liberated on 10 September 1944.[13] The city was under long-range bombardment by the German V-3 cannon in December 1944 and January 1945.

After the war, Luxembourg ended its neutrality, and became a founding member of several inter-governmental and supra-governmental institutions. In 1952, the city became the headquarters of the High Authority of the European Coal and Steel Community. In 1967, the High Authority was merged with the commissions of the other European institutions; although Luxembourg City was no longer the seat of the ECSC, it hosted some part-sessions of the European Parliament until 1981.[14] Luxembourg remains the seat of the European Parliament's secretariat, as well as the Court of Justice of the European Union, the European Court of Auditors, and the European Investment Bank. Several departments of the European Commission are also based in Luxembourg.[6] The Council of the EU meets in the city for the months of April, June and October annually.[6]

Geography

Topography

Luxembourg City lies on the southern part of the Luxembourg plateau, a large Early Jurassic sandstone formation that forms the heart of the Gutland, a low-lying and flat area that covers the southern two-thirds of the country.

The city centre occupies a picturesque site on a salient, perched high on precipitous cliffs that drop into the narrow valleys of the Alzette and Pétrusse rivers, whose confluence is in Luxembourg City. The 70 m (230 ft) deep gorges cut by the rivers are spanned by many bridges and viaducts, including the Adolphe Bridge, the Grand Duchess Charlotte Bridge, and the Passerelle. Although Luxembourg City is not particularly large, its layout is complex, as the city is set on several levels, straddling hills and dropping into the two gorges.

The commune of Luxembourg City covers an area of over 51 km2 (20 sq mi), or 2% of the Grand Duchy's total area. This makes the city the fourth-largest commune in Luxembourg, and by far the largest urban area. Luxembourg City is not particularly densely populated, at about 1,700 people per km2; large areas of Luxembourg City are maintained as parks, forested areas, or sites of important heritage (particularly the UNESCO sites), while there are also large tracts of farmland within the city limits.

Quarters of Luxembourg City

Luxembourg City is subdivided into twenty-four quarters (French: quartiers), which cover the commune in its entirety. The quarters generally correspond to the major neighbourhoods and suburbs of Luxembourg City, although a few of the historic districts, such as Bonnevoie, are divided between two quarters.[citation needed]

Climate

Luxembourg City has an oceanic climate (Cfb), with moderate precipitation, cold to cool winters and warm summers. It is cloudy about two-thirds of the year.[citation needed]

| Climate data for Luxembourg City (1991–2020, extremes 1947–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.9 (57.0) |

19.8 (67.6) |

23.5 (74.3) |

27.9 (82.2) |

31.6 (88.9) |

35.4 (95.7) |

39.0 (102.2) |

37.9 (100.2) |

31.5 (88.7) |

26.0 (78.8) |

19.8 (67.6) |

14.7 (58.5) |

39.0 (102.2) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 10.7 (51.3) |

12.2 (54.0) |

17.4 (63.3) |

22.9 (73.2) |

26.6 (79.9) |

30.1 (86.2) |

31.9 (89.4) |

31.5 (88.7) |

25.6 (78.1) |

20.9 (69.6) |

14.6 (58.3) |

10.8 (51.4) |

33.5 (92.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.8 (38.8) |

5.2 (41.4) |

9.8 (49.6) |

14.4 (57.9) |

18.4 (65.1) |

21.7 (71.1) |

23.9 (75.0) |

23.5 (74.3) |

19.0 (66.2) |

13.5 (56.3) |

7.7 (45.9) |

4.5 (40.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) |

2.2 (36.0) |

5.7 (42.3) |

9.6 (49.3) |

13.5 (56.3) |

16.7 (62.1) |

18.7 (65.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

14.3 (57.7) |

9.9 (49.8) |

5.2 (41.4) |

2.3 (36.1) |

9.8 (49.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −1.0 (30.2) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

2.0 (35.6) |

5.1 (41.2) |

8.7 (47.7) |

11.8 (53.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

13.6 (56.5) |

10.3 (50.5) |

6.6 (43.9) |

2.8 (37.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

6.1 (43.0) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −8.0 (17.6) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

6.0 (42.8) |

9.1 (48.4) |

8.3 (46.9) |

5.5 (41.9) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−10.4 (13.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −17.8 (0.0) |

−20.2 (−4.4) |

−14.4 (6.1) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

0.9 (33.6) |

4.5 (40.1) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−15.3 (4.5) |

−20.2 (−4.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 72.0 (2.83) |

59.0 (2.32) |

57.0 (2.24) |

49.0 (1.93) |

71.2 (2.80) |

75.6 (2.98) |

71.5 (2.81) |

71.9 (2.83) |

66.2 (2.61) |

76.6 (3.02) |

72.1 (2.84) |

89.4 (3.52) |

831.5 (32.74) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 17.3 | 15.4 | 14.8 | 12.7 | 14.0 | 13.3 | 13.7 | 13.2 | 12.2 | 15.2 | 17.5 | 18.1 | 177.4 |

| Average snowy days | 7.5 | 7.6 | 3.6 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 2.3 | 6.8 | 29.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 88 | 83 | 74 | 67 | 68 | 68 | 67 | 68 | 75 | 84 | 89 | 90 | 77 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 52.0 | 79.5 | 137.1 | 197.5 | 226.3 | 241.2 | 257.6 | 237.1 | 174.9 | 106.7 | 51.1 | 41.9 | 1,802.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 18.8 | 29.4 | 34.0 | 44.1 | 44.8 | 46.7 | 51.0 | 51.7 | 42.7 | 31.8 | 19.8 | 16.1 | 35.9 |

| Source 1: Meteolux (percent sunshine 1981–2010)[15][16][17] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Infoclimat[18] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: Le Portail des Statistiques du Luxembourg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Government

Local government

Under the Luxembourgish constitution, local government is centred on the city's communal council. Consisting of twenty-seven members (fixed since 1964), each elected every six years on the second Sunday of October and taking office on 1 January of the next year,[19] the council is the largest of all communal councils in Luxembourg. The city is nowadays considered a stronghold of the Democratic Party (DP),[20] which is the second-largest party nationally. The Democratic Party is the largest party on the council, with ten councillors.[21]

The city's administration is headed by the mayor, who is the leader of the largest party on the communal council. After Xavier Bettel became Luxembourg's new prime minister on 4 December 2013, Lydie Polfer (DP) was sworn in as new mayor of Luxembourg on 17 December of the same year. Since the last elections the mayor leads the cabinet, the collège échevinal, in which the DP forms a coalition with CSV. Unlike other cities in Luxembourg, which are limited to four échevins at most, Luxembourg is given special dispensation to have six échevins on its collège échevinal.[22]

National government

Luxembourg City is the seat for the Luxembourg Government. The Grand Ducal Family of Luxembourg lives at Berg Castle in Colmar-Berg.

For national elections to the Chamber of Deputies, the city is located in the Centre constituency.[citation needed]

European institutions

Luxembourg City is the seat of several institutions, agencies and bodies of the European Union, including the Court of Justice of the European Union, the European Commission, the secretariat of the European Parliament, the European Court of Auditors and the European Investment Bank. The majority of these institutions are located in the Kirchberg quarter, in the northeast of the city.[23]

Culture

Despite the city's small size, it has several notable museums: the recently renovated National Museum of History and Art (MNHA), the Luxembourg City History Museum, the new Grand Duke Jean Museum of Modern Art (Mudam) and National Museum of Natural History (NMHN).

Luxembourg was the first city to be named European Capital of Culture twice. The first time was in 1995. In 2007, along with the Romanian city of Sibiu, the European Capital of Culture[24] was to be a cross-border area consisting of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, the Rheinland-Pfalz and Saarland in Germany, the Walloon Region and the German-speaking part of Belgium, and the Lorraine area in France. The event was an attempt to promote mobility and the exchange of ideas, crossing borders in all areas, physical, psychological, artistic and emotional.[citation needed]

Luxembourg City is also famed for its wide selection of restaurants and cuisines, including four Michelin starred establishments.[25]

UNESCO World Heritage Site

The city of Luxembourg is on the UNESCO World Heritage List as City of Luxembourg: its Old Quarters and Fortifications, on account of the historical importance of its fortifications.[26] In addition to its two main theatres, the Grand Théâtre de Luxembourg and the Théâtre des Capucins, there is a new concert hall, the Philharmonie, as well as a conservatory with a large auditorium. Art galleries include the Villa Vauban, the Casino Luxembourg and Am Tunnel.[27]

The site is located mainly in Ville Haute (Uewerstad).

Sport

The ING Europe Marathon has been contested annually in the capital since June 2006. It attracted 11,000 runners and over 100,000 spectators during the 2014 edition.

The Luxembourg Open is a tennis tournament held since 1991 in the capital. The tournament runs from 13 to 21 October. BGL BNP Paribas, one of the more famous sponsors in the world of tennis, was the contracted title sponsor of the tournament until 2014.

The Stade de Luxembourg, situated in Gasperich, southern Luxembourg City, is the country's national stadium and largest sports venue in the country with a capacity of 9,386 for sporting events, including football and rugby union, and 15,000 for concerts.[28] The largest indoor venue in the country is d'Coque, Kirchberg, north-eastern Luxembourg City, which has a capacity of 8,300. The arena is used for basketball, handball, gymnastics, and volleyball, including the final of the 2007 Women's European Volleyball Championship. D'Coque also includes an Olympic-size swimming pool.[29]

The two football clubs of the city of Luxembourg; Racing FC Union Luxembourg and F.C. Luxembourg City, play in the country's highest league, the BGL Ligue, and second-tier, Division of Honour, respectively. The Stade de Luxembourg hosts the Luxembourg national football team.

Places of interest

Places of interest include the Gothic Revival Cathedral of Notre Dame, the fortifications, Am Tunnel (an art gallery underground), the Grand Ducal Palace, the Gëlle Fra war memorial, the casemates, the Neimënster Abbey, the Place d'Armes, the Adolphe Bridge and the city hall. The city is home to the RTL Group.

The Second World War Luxembourg American Cemetery and Memorial is located within the city limits of Luxembourg at Hamm. This cemetery is the final resting place of 5,076 American military dead, including General George S. Patton. There is also a memorial to 371 Americans whose remains were never recovered or identified.

Transport

Highways

Luxembourg is situated in the heart of Europe in the Gold Triangle between Frankfurt, Paris, and Amsterdam. It is therefore connected to several motorways and international routes.[citation needed]

- A1 (E44): to Grevenmacher and Trier (Germany).

- A3 (E25): to Dudelange and Thionville (France).

- A4: to Esch-sur-Alzette and to A13 to Pétange, Athus (Belgium) and Longwy (France)

- A6 (E25 / E411): to Arlon and Brussels.

- A7 (E421): to Mersch and Ettelbruck.

Public transport

Public transport in Luxembourg City has been free since 2020, including rail, bus and tram.[30]

Rail

Luxembourg City is served by five rail stations operated by the state rail company, the Société Nationale des Chemins de Fer Luxembourgeois (CFL), including the principal station and terminus of all rail lines in the Grand Duchy, Luxembourg station. Stations in Luxembourg City are served by domestic rail services operated by CFL, as well as international rail services, operated by CFL, and German, Belgian, and French service providers. Additionally, Luxembourg station is connected to the French LGV Est network, providing high-speed services on to Paris and Strasbourg. Services to Basel and Zürich in Switzerland are available via two daily scheduled international trains.[31]

Bus

Luxembourg City has a network of 40[32] bus routes, operated by the municipal transport authority, Autobus de la Ville de Luxembourg (AVL), partly subcontracted to private bus companies. There is also a free bus service linking the Glacis to Luxembourg station, the "Joker Line" for seniors, and a "City night network". A "Park & Ride" scheme is operated by the city with five carparks connected to the bus network. In addition to AVL buses, CFL and RGTR operate regional buses to other locales in Luxembourg and nearby cities in Germany and France.[citation needed]

Tram

Between 1875 and 1964, the city was covered by an extensive tram network. In December 2017, trams were reintroduced to the capital, with the phased opening of a new line, which currently runs between Kirchberg and Gasperich, via the city centre.[33][34] An extension to Luxembourg Airport is expected to be operational by March 2025.[35] Future lines to extend the network are currently in the planning stages.[36]

Air

Luxembourg City is served by the only international airport in the country: Luxembourg Airport (codes: IATA: LUX, ICAO: ELLX). Accessibility to the airport, situated in the commune of Sandweiler, 6 kilometres (3.7 miles) from the city centre, is provided via the municipal bus network, with a tram connection due to be completed by early 2024.[37] The airport is the principal hub for Luxembourg's flag carrier, Luxair, and one of the world's largest cargo airlines, Cargolux.[38]

International relations

Luxembourg is a member of the QuattroPole union of cities, along with Trier, Saarbrücken, and Metz (neighbouring countries: Germany and France).[39]

Twin towns – Sister cities

Luxembourg is twinned with:

Metz, France

Metz, France Tambov Oblast, Russia

Tambov Oblast, Russia Prague, Czech Republic[40]

Prague, Czech Republic[40]

Image gallery

- Luxembourg City as seen from a Sentinel-2 satellite

- Skyline of the Hollerich quarter

- The gorges and Adolphe Bridge

- View of the Luxembourg center cityscape from Cité Judiciaire

- The Center of Luxembourg City with the Pulvermuhl Viaduct

- Cité Judiciaire in Luxembourg

See also

- Cessange

- Eurovision Song Contest 1962

- Eurovision Song Contest 1966

- Eurovision Song Contest 1973

- Eurovision Song Contest 1984

- Limes Luxemburgensis

- List of mayors of Luxembourg City

- Strassen, Luxembourg

Notes

- ^ Luxembourgish: [ˈlətsəbuəɕ] ⓘ

French: [lyksɑ̃buʁ] ⓘ

German: [ˈlʊksm̩bʊʁk] ⓘ - ^ Luxembourgish: [ʃtaːt ˈlətsəbuəɕ] ⓘ or [tʃtaːt]

French: [vil də lyksɑ̃buʁ]

German: [ʃtat ˈlʊksm̩bʊʁk] or [ˈlʊksm̩bʊʁk ˌʃtat]

References

- ^ "Great Circle Distances between Cities". United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on 26 March 2005. Retrieved 23 July 2006.

- ^ "La ville en chiffres". vdl.lu. Archived from the original on 27 September 2024. Retrieved 5 October 2024.

- ^ "The capital of Luxembourg counts 110,499 inhabitants". www.luxembourg.public.lu. Archived from the original on 3 October 2019. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- ^ "Luxembourg". International Monetary Fund. January 2024. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ^ "Quality of living city ranking". Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d "The European institutions in Luxembourg". luxembourg.public.lu. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ "The Fortress". Luxembourg City Tourism Office. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2006.

- ^ a b Kreins (2003), p. 64

- ^ "World Heritage List – Luxembourg" (PDF). UNESCO. 1 October 1993. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2004. Retrieved 19 July 2006.

- ^ (in French) Treaty of London, 1867 Archived 22 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Article IV. GWPDA. Retrieved 19 July 2006.

- ^ "Luxembourg's history : Mutiny in the Grand Duchy". today.rtl.lu. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ a b May, Guy (2002). "Die Straßenbezeichnungen der Stadt Luxemburg unter deutscher Besatzung (1940–1944)" (PDF). Ons Stad (in German) (71): 30–32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Thewes (2003), p. 121

- ^ "Alcide De Gasperi Building". Centre Virtuel de la Connaissance sur l'Europe. 16 June 2006. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2006.

- ^ "Annuaire climatologique 2021" (in French). Meteolux. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ "Données Climatologiques" (PDF). Meteolux. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 January 2017. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ^ "Normales et extrêmes" (in French). Administration de l’Aéroport de Luxembourg. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ "Climatologie de l'année à Luxembourg" (in French). Infoclimat. Archived from the original on 22 November 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ "Organisation et fonctionnement des organes politiques". Ville de Luxembourg (in French). Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ^ Hansen, Josée (8 October 1999). "Cliff-hanger". Lëtzebuerger Land (in French). Archived from the original on 16 August 2007. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

- ^ "Members of the Municipal Council". Ville de Luxembourg. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ "Organisation des communes – Textes Organiques" (PDF). Code administratif Luxembourgeois (in French). Service central de législation. 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

- ^ "Kirchberg Plateau in Luxembourg City". www.luxembourg-city.com. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ "Luxembourg and Greater Region, European Capital of Culture 2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ ""Guide Michelin 2012: Le Luxembourg perd des étoiles"". Archived from the original on 23 November 2011.

- ^ "Culture in Luxembourg". Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ "Art et Culture", Ville de Luxembourg. (in French) Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ "Stade de Luxembourg (Stade National) – StadiumDB.com". stadiumdb.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ "Infrastructure". www.coque.lu. 22 February 2019. Archived from the original on 1 October 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ "Public transport". luxembourg.public.lu. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "A guide to French Railway's TGV high-speed trains". www.seat61.com. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ "En bus". vdl.lu.

- ^ Bauldry, Jess (12 July 2017). "Tram returns to city after 50 years". delano.lu. Archived from the original on 21 February 2023. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ Fick, Maurice (7 July 2024). "New section opening on Sunday: Tram passengers to expect 'several new exciting changes': Luxtram director". today.rtl.lu. Retrieved 24 August 2024.

- ^ Weyrich, Frank (27 September 2024). "Tram to run to Luxembourg airport from March, minister says". luxtimes.lu. Archived from the original on 7 October 2024. Retrieved 7 October 2024.

- ^ Carette, Julien (2 May 2022). "Tram network to grow to four lines by 2035". delano.lu. Archived from the original on 15 February 2023. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ "Tram network to reach Findel airport by 2024". RTL Today. Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "Luxembourg Airport | My Journey Starts Here". Luxembourg Airport. Archived from the original on 30 December 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ "Futurium | Border Focal Point Network - QuattroPole: a cross-border network in the heart of Europe". futurium.ec.europa.eu (in Italian). Archived from the original on 20 June 2023. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ "Partnerská města HMP". zahranicnivztahy.praha.eu (in Czech). Prague. Archived from the original on 25 June 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- Kreins, Jean-Marie (2003). Histoire du Luxembourg (in French) (3rd ed.). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 978-2-13-053852-3.

- Thewes, Guy (July 2003). Les gouvernements du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg depuis 1848 (PDF) (in French) (Édition limitée ed.). Luxembourg City: Service Information et Presse. ISBN 2-87999-118-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 February 2004. Retrieved 6 July 2006.

Bibliography

Further reading

- Makos, Adam (2019). Spearhead (1st ed.). New York: Ballantine Books. p. 48. ISBN 9780804176729. LCCN 2018039460. OL 27342118M.

- Philippart, Robert L. (2021). "La ville intègre sa périphérie" (PDF). ons stad (in French) (123): 18–23.

- Thewes, Guy; Wagener, Danièle (1995). "La Ville de Luxembourg en 1795" (PDF). ons stad (in French) (49): 4–7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- Thewes, Guy (2002). "Nationalsozialistische Architektur in Luxemburg" (PDF). ons stad (in German) (71): 25–29. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 February 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- Thewes, Guy (2004). "L'évacuation des déchets de la vie urbaine sous l'Ancien Régime" (PDF). ons stad (in French) (75): 30–33. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- Thewes, Guy (2012). "Le "grand renfermement" – La ville à l'âge de la forteresse" (PDF). ons stad (in French) (99): 10–13. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 September 2016.

- Thewes, Guy (2013). "Luxembourg, ville dangereuse sous l'Ancien Régime? – Police et sécurité au XVIIIe siècle" (PDF). ons stad (in French) (104): 58–61. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.