Fort Jackson (Virginia)

| Fort Jackson | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Civil War defenses of Washington, D.C. | |

| Arlington, Virginia | |

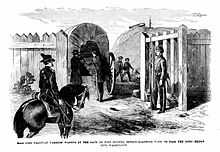

The Long Bridge and two of its guards, as seen from the Washington side of the Potomac River. | |

| Coordinates | 38°52′16″N 77°02′27″W / 38.87111°N 77.04083°W |

| Type | Timber fort |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | Union Army |

| Condition | Dismantled |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1861 |

| Built by | U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

| In use | 1861-1865 |

| Materials | Earth, timber |

| Demolished | 1865 |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Fort Jackson was an American Civil War-era fortification in Virginia that defended the southern end of the Long Bridge, near Washington, D.C. Long Bridge connected Washington, D.C. to Northern Virginia and served as a vital transportation artery for the Union Army during the war. Fort Jackson was named for Jackson City, a seedy suburb of Washington that had been established on the south side of the Long Bridge in 1835. It was built in the days immediately following the Union Army's occupation of Northern Virginia in May 1861. The fort was initially armed with four cannon used to protect the bridge, but these were removed after the completion of the Arlington Line, a line of defenses built to the south. After 1862, the fort lacked weapons except for small arms and consisted of a wooden palisade backed by earthworks. Two cannon were restored to the fort in 1864 following the Battle of Fort Stevens. The garrison consisted of a single company of Union soldiers who inspected traffic crossing the bridge and guarded it from potential saboteurs.

Following the final surrender of the Confederate States of America in 1865, Fort Jackson was abandoned. The lumber used in its construction was promptly salvaged for firewood and construction materials and, due to its proximity to the Long Bridge, the earthworks were flattened in order to provide easier access to Long Bridge. In the early 20th century, the fort's site was used for the footings and approaches to several bridges connecting Virginia and Washington. Today, no trace of the fort remains, though the site of the fort is contained within Arlington County's Long Bridge Park, and a National Park Service 2004 survey of the site indicated some archaeological remnants may still remain beneath the park.

Occupation of Arlington

Before the outbreak of the Civil War, Alexandria County (renamed Arlington County in 1920), the county in Virginia closest to Washington, D.C., was a predominantly rural area. Part of the original ten-mile-square District of Columbia, the land now comprising the county was retroceded to Virginia in a July 9, 1846, act of Congress that took effect in 1847.[1] Most of the county is hilly, and at the time, most of the county's population was concentrated in the city of Alexandria, at the far southeastern corner of the county. In 1861, the rest of the county largely consisted of scattered farms, the occasional house, fields for grazing livestock, and Arlington House, owned by Mary Custis, wife of Robert E. Lee.[2] The county was connected to nearby Washington via the Long Bridge, which spanned the Potomac River. On the river flats of the Virginia side of the river was Jackson City,[3] a seedy entertainment district named after President Andrew Jackson and home to several racetracks, gambling halls, and saloons.[4]

Following the surrender of Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, on April 14, 1861, President Abraham Lincoln declared that "an insurrection existed", and called for 75,000 troops to be called up to quash the rebellion.[5] The move sparked resentment in many other southern states, which promptly moved to convene discussions of secession. The Virginia State Convention passed "an ordinance of secession" and ordered a May 23 referendum to decide whether or not the state should secede from the Union.[6] The U.S. Army responded by creating the Department of Washington, which united all Union troops in the District of Columbia and Maryland under one command.[7]

Brigadier General J.F.K. Mansfield, commander of the Department of Washington, argued that Northern Virginia should be occupied as soon as possible in order to prevent the possibility of the Confederate Army mounting artillery on the hills of Arlington and shelling government buildings in Washington. He also urged the erection of fortifications on the Virginia side of the Potomac River to protect the southern terminuses of the Chain Bridge, Long Bridge, and Aqueduct Bridge. His superiors approved these recommendations, but decided to wait until after Virginia voted for or against secession.[8]

On May 23, 1861, Virginia voted by a margin of 3 to 1 in favor of leaving the Union. That night, U.S. Army troops began crossing the bridges linking Washington, D.C. to Virginia. The march, which began at 10 p.m. on the night of the 23rd, was described in colorful terms by the New York Herald two days later:

There can be no more complaints of inactivity of the government. The forward march movement into Virginia, indicated in my despatches last night, took place at the precise time this morning that I named, but in much more imposing and powerful numbers.

About ten o'clock last night four companies of picked men moved over the Long Bridge, as an advance guard. They were sent to reconnoitre, and if assailed were ordered to signal, when they would have been reinforced by a corps of regular infantry and a battery....

At twelve o'clock the infantry regiment, artillery and cavalry corps began to muster and assume marching order. As fast as the several regiments were ready they proceeded to the Long Bridge, those in Washington being directed to take that route.

The troops quartered at Georgetown, the Sixty-ninth, Fifth, Eighth and Twenty-eighth New York regiments, proceeded across what is known as the chain bridge, above the mouth of the Potomac Aqueduct, under the command of General McDowell. They took possession of the heights in that direction.

The imposing scene was at the Long Bridge, where the main body of the troops crossed. Eight thousand infantry, two regular cavalry companies and two sections of Sherman's artillery battalion, consisting of two batteries, were in line this side of the Long Bridge at two o'clock.[9]

The occupation of Northern Virginia was peaceful, with the exception of the town of Alexandria. There, as Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth, commander of the New York Fire Zouaves (11th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment), entered a local hotel to remove the Confederate flag flying above it, he was shot and killed by James Jackson, the proprietor. Ellsworth was one of the first men killed in the American Civil War.[10]

Planning and construction

Over 13,000 men marched into northern Virginia on May 25, bringing with them "a long train of wagons filled with wheelbarrows, shovels, &c."[9] These implements were put to work even as thousands of men marched further into Virginia. Engineer officers under the command of then-Colonel John G. Barnard accompanied the army and began building fortifications and entrenchments along the banks of the Potomac River in order to defend the bridges that crossed it.[11] By sunrise on the morning of the 24th, ground had already been broken on the first two forts comprising the Civil War defenses of Washington — Fort Runyon and Fort Corcoran. Within a week, other, smaller forts had sprung up as supporting works. Fort Jackson, built to the northeast of Fort Runyon about fifty yards south of the intersection of the present-day 14th Street Bridge and the Virginia shore and armed with four cannon, was one of these.[11][12]

Owing to its large physical size and extensive armament, Fort Runyon was intended to be the primary fort defending the Long Bridge. Fort Jackson, located at the southern end of the bridge, received four cannon and was intended as a guard post for soldiers inspecting civilian traffic crossing the bridge and to detour any Confederate saboteurs that might attempt to destroy the bridge.[13] To man the fort's four guns, 60 artillerymen were assigned, bringing the total garrison to 200 men.[14]

Wartime use

On July 14, 1861, Company E of the 21st New York Volunteer Infantry was assigned to garrison Fort Jackson.[15] On August 31, the 21st New York was ordered to Fort Cass, Virginia, and was later involved in the Second Battle of Bull Run.[16] No information exists on the unit that replaced it in garrisoning Fort Jackson.

Following the completion of the Arlington Line, which was built several miles to the southwest of Fort Jackson, atop the heights of Arlington, the maintenance of Forts Jackson and Runyon was neglected. The two forts had largely been made redundant by the newer, stronger works atop the hills, and it was believed that neither played a crucial role any longer in the defenses of Washington. Fort Jackson was kept in service only as an inspection station for traffic crossing Long Bridge.[17]

Railroad and rebuilding

In 1863, a new railroad bridge was constructed adjacent to the Long Bridge as part of a plan to strengthen the logistics of the Army of the Potomac as it operated in northern Virginia. An extension of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, the bridge would be used until the turn of the century before being replaced. Owing to the weight of the railroad and the weak strength of the bridge, no locomotives were allowed on the bridge. Prior to crossing the Potomac, the train would detach its locomotive and be pulled across the bridge by a team of horses.[18]

In order to provide space for the railroad tracks, the gates of Fort Jackson had to be removed. These were eventually replaced, but the wide opening needed for the tracks proved to have a detrimental effect on the fort's defensive ability.[19] An 1864 report by Lt. Col. Barton S. Alexander, the aide de camp to Gen. John Gross Barnard, chief engineer of the defenses of Washington, described the way Fort Jackson had been allowed to fall into disrepair:

The defense of the bridge is very imperfect, owing to the dilapidation and decay of Fort Jackson. The railroad cuts through the parapet and there are no gates except at turnpike entrance. The railroad crosses the ditch of the fort on a bridge which is not floored, but an enemy could soon cover it so as to make it passable. Cavalry could also ride around to the lower side of the fort and come in on the bridge.[20]

To fix the problems at Fort Jackson, Alexander recommended the addition of an artillery section, a second company of infantry, and various improvements to the fort itself.[20] Spurred in part by the Confederate attack on Fort Stevens north of Washington, several improvements were made, including the restoration of gates that had been removed when the railroad line was constructed.[19] Gen. Christopher Columbus Augur, commander of the Department of Washington, recommended that Fort Jackson be assigned two light guns as armament during the reconstruction.[21]

Post-war use

After the surrender of General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865, the primary reason for manned defenses protecting Washington ceased to exist. Initial recommendations by Colonel Barton S. Alexander, then-chief engineer of the Washington defenses, were to divide the defenses into three classes: those that should be kept active (first-class), those that should be mothballed and kept in a reserve state (second-class), and those that should be abandoned entirely (third-class). Due to its rear-area nature and the fact that inspections were no longer needed to protect the Long Bridge against sabotage, Fort Jackson fell into the third-class category.[22]

The lumber used in the construction of Fort Jackson was either sold for salvage or scavenged by squatters, most of whom were freed slaves traveling north in a search for new lives following the ending of slavery in the United States. Many settled in the area of the former Fort Runyon, and it seems likely that the lumber of Fort Jackson would have been a ready source of firewood.[23]

All the forts around or overlooking the city are dismantled, the guns taken out of them, the land resigned to its owners. Needy negro squatters, living around the forts, have built themselves shanties of the officers' quarters, pulled out the abatis for firewood, made cord wood or joists out of the log platforms for the guns, and sawed up the great flag-staffs into quilting poles or bedstead posts... The strolls out to these old forts are seedily picturesque. Freedmen, who exist by selling old horse-shoes and iron spikes, live with their squatter families where, of old, the army sutler kept the canteen; but the grass is drawing its parallels nearer and nearer the magazines. Some old clothes, a good deal of dirt, and forgotten graves, make now the local features of war."[23]

By the turn of the century, the site of Fort Jackson had become the footings for a new railroad bridge, constructed in 1903. Three years later, a road bridge was constructed just to the west.[24] A brickworks was also located nearby, sometimes utilizing the clay that formed the bastions of Fort Runyon as raw material for the bricks that would later go into the walls of Washington homes.[25] These projects obliterated what little trace there was of Fort Jackson.

Today, a CSX Corporation railroad bridge runs through the site of Fort Jackson, and the Potomac shoreline just south of the bridge is being studied by the National Park Service as one possible site for an Arlington County boathouse.[26] Just south of the federal George Washington Memorial Parkway, between the CSX tracks and I-395, is Arlington County's Long Bridge Park.[27] The northern end of the park, not yet developed for recreational use, may include part of the site of Fort Jackson. A National Park Service study commissioned during the ongoing review of potential boathouse sites included an observation that historical artifacts from Fort Jackson may still be present at the site.[26]

Notes

- ^ Alexandria County, District of Columbia Archived 2008-05-11 at the Wayback Machine Arlington (Va.) Historical Society. Accessed June 18, 2008.

- ^ Evacuation of Arlington House U.S. National Park Service, March 27, 2002. Accessed June 18, 2008.

- ^ Sketch of the seat of war in Alexandria & Fairfax Cos. V.P. Corbett, Washington, D.C., 1861. U.S. Library of Congress, LC Civil War Maps (2nd ed.), page 522.

- ^ The Heritage behind Long Bridge Park Archived 2007-11-28 at the Wayback Machine "Long Bridge Park," Department of Parks, Recreation, and Cultural Resources. Arlington, Virginia. Accessed June 13, 2008.

- ^ Long, pp. 47-50.

- ^ Long, April 17

- ^ Long, p. 67

- ^ Cooling, 1991, pp. 32-26, 41.

- ^ a b New York Herald. "THE INSURRECTION. ADVANCE OF THE FEDERAL TROOPS INTO VIRGINIA," Washington, D.C., May 24, 1861.

- ^ Ames W. Williams, "The Occupation of Alexandria," Virginia Cavalcade, Volume 11, (Winter 1961-62), pp. 33-34.

- ^ a b Cooling, 1991, p. 37.

- ^ Cooling III, Benjamin Franklin; Owen II, Walton H. (2010). "Touring the Forts South of the Potomac: Fort Runyan and Fort Jackson". Mr. Lincoln's Forts: A Guide to the Civil War Defenses of Washington (New ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-8108-6307-1. LCCN 2009018392. OCLC 665840182. Retrieved 2018-03-07 – via Google Books.

- ^ Military-use Structures, "Fort Runyon" Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Arlington (Va.) Historical Society. Accessed June 18, 2008.

- ^ Scott, et al., Volume 5, Chapter 14, p. 628.

- ^ History of the 21st New York State Volunteers New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center. October 20, 2006. Accessed June 18, 2008.

- ^ 21st Infantry Regiment "History" New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center. October 20, 2006. Accessed June 18, 2008.

- ^ Williams, Duane J. Civil War Diaries. iUniverse, 2002. Page 27.

- ^ Norfolk Southern Railway History, "Orange and Alexandria Railroad" Archived 2016-11-11 at the Wayback Machine Piedmont Railroaders, Spring 2002. Accessed June 19, 2008.

- ^ a b List of Virginia Forts, "Fort Jackson" Pete Payette and Phil Payette. November 17, 2007. Accessed June 19, 2008.

- ^ a b Scott, et al., Volume 37 (Part 2), Chapter 49, Page 85.

- ^ Scott, et al., Volume 37 (Part 2), Chapter 49, Page 495.

- ^ Scott, et al., Volume 46 (Serial 97), Part 3, p. 1130.

- ^ a b George Alfred Townsend, Washington, Outside and Inside. A Picture and A Narrative of the Origin, Growth, Excellences, Abuses, Beauties, and Personages of Our Governing City. Hartford, CT; James Betts & Co., 1873. p. 640-641.

- ^ 14th Street Bridge Scott M. Kozel, Roadstothefuture.com. June 20, 2004. Accessed June 19, 2008.

- ^ Snowden, William Henry. Some Old Historic Landmarks of Virginia and Maryland G.H. Ramey & Son, 1902. Page 7.

- ^ a b National Park Service boathouse project (PDF) U.S. National Park Service. June 2004. Accessed June 19, 2008.

- ^ Long Bridge Park Archived 2008-10-03 at the Wayback Machine County of Arlington, Virginia. Accessed June 19, 2008.

References

- Cooling, Benjamin Franklin III (1991). Symbol, Sword, and Shield: Defending Washington During the Civil War (2nd revised ed.). Shippensburg, Pennsylvania: White Mane Publishing Company. ISBN 0942597249. LCCN 91026949. OCLC 24107616. Retrieved March 7, 2018 – via Google Books.

- Long, E.B.; Long, Barbara (1971). The Civil War Day by Day: An Almanac 1861-1865. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc. ISBN 9780307819048. LCCN 73163653. OCLC 650017632. Retrieved March 7, 2018 – via Google Books.

- Scott, Robert N. (ed.). The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Published under the direction of the Secretary of War. Series 1 (Military Operations). Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office. LCCN 03003452. OCLC 224137463. (See: Official Records of the War of the Rebellion)

External links