Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic

Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic Lietuvos Tarybų Socialistinė Respublika (Lithuanian) Литовская Советская Социалистическая Республика (Russian) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940–1941 1944–1990 | |||||||||

Flag (1953–1988) State emblem (1940–1990) | |||||||||

| Motto: Visų šalių proletarai, vienykitės! (Lithuanian) "Workers of the world, unite!" | |||||||||

| Anthem: Tautiška giesmė (1944–1950, 1988–1990) Anthem of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (1950–1988) | |||||||||

Location of annexed Lithuania (red) within the Soviet Union | |||||||||

| Status | Internationally unrecognized territory occupied by the Soviet Union (1940–1941; 1944–1990) | ||||||||

| Capital | Vilnius | ||||||||

| Common languages | Lithuanian · Russian | ||||||||

| Religion | Secular state (de jure) State atheism (de facto) | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Lithuanian Soviet | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary Marxist-Leninist one-party soviet socialist republic (1940–1989) Unitary multi-party parliamentary republic (1989–1990) | ||||||||

| First Secretary | |||||||||

• 1940–1974 | Antanas Sniečkus | ||||||||

• 1974–1987 | Petras Griškevičius | ||||||||

• 1987–1988 | Ringaudas Songaila | ||||||||

• 1988–1990 | Algirdas Brazauskas | ||||||||

| Head of state | |||||||||

• 1940–1967 (first) | Justas Paleckis | ||||||||

• 1990 (last) | Vytautas Landsbergis | ||||||||

| Head of government | |||||||||

• 1940–1956 (first) | Mečislovas Gedvilas | ||||||||

• 1985–1990 (last) | Vytautas Sakalauskas | ||||||||

| Legislature | Supreme Soviet | ||||||||

| Historical era | World War II · Cold War | ||||||||

| 16 June 1940 | |||||||||

• SSR established | 21 July 1940 | ||||||||

| 3 August 1940 | |||||||||

| June 1941 | |||||||||

• Soviet re-occupation SSR re-established | September–November 1944 | ||||||||

| 1988 | |||||||||

• Sovereignty declared | 18 May 1989 | ||||||||

| 11 March 1990 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1989 | 65,200 km2 (25,200 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1989 | 3,689,779 | ||||||||

| Currency | Soviet rouble (Rbl) (SUR) | ||||||||

| Calling code | +7 012 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Lithuania | ||||||||

The Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (Lithuanian SSR; Lithuanian: Lietuvos Tarybų Socialistinė Respublika; Russian: Литовская Советская Социалистическая Республика, romanized: Litovskaya Sovetskaya Sotsialisticheskaya Respublika), also known as Soviet Lithuania or simply Lithuania, was de facto one of the constituent republics of the Soviet Union between 1940–1941 and 1944–1990. After 1946, its territory and borders mirrored those of today's Republic of Lithuania, with the exception of minor adjustments to its border with Belarus.[1]

During World War II, the previously independent Republic of Lithuania was occupied by the Red Army on 16 June 1940, in conformity with the terms of the 23 August 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, and established as a puppet state on 21 July.[2] Between 1941 and 1944, the German invasion of the Soviet Union caused its de facto dissolution. However, with the retreat of the Germans in 1944–1945, Soviet hegemony was re-established and continued for forty-five years. As a result, many Western countries continued to recognize Lithuania as an independent, sovereign de jure state subject to international law, represented by the legations appointed by the pre-1940 Baltic states, which functioned in various places through the Lithuanian Diplomatic Service.

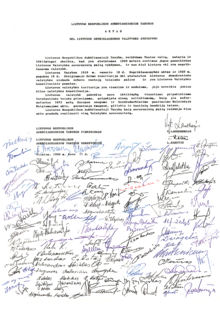

On 18 May 1989, the Lithuanian SSR declared itself to be a sovereign state, though still part of the USSR. On 11 March 1990, the Republic of Lithuania was re-established as an independent state, the first Soviet Republic to leave Moscow and leading other states to do so. Lithuania considered the Soviet occupation and annexation illegal and, like the other two Baltic States, claimed state continuity. This legal continuity has been recognised by most Western powers. The Soviet authorities considered the independence declaration illegal, but after the January Events in Lithuania and failed 1991 Soviet coup attempt in Moscow, the Soviet Union itself recognized Lithuanian independence on 6 September 1991.

History

Background

On 23 August 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact,[3] which contained agreements to divide Europe into spheres of influence, with Lithuania falling into Germany's sphere of influence. On 28 September 1939, the USSR and Germany signed the Frontier Treaty and its secret protocol, by which Lithuania was placed in the USSR's sphere of influence in exchange for Germany gaining an increased share of Polish territory, which had already been occupied.[4] The next day, the USSR offered Lithuania an agreement on the establishment of Soviet military bases in its territory. During the negotiations, the Lithuanian delegation was told of the division of the spheres of influence. The Soviets threatened that if Lithuania refused to host the bases, Vilnius could be annexed to Belarus (at that time the majority of population in Vilnius and Vilnius region were Polish people). In these circumstances a Lithuania–USSR agreement on mutual assistance was signed in Moscow on 10 October 1939, allowing a Soviet military presence in Lithuania.[5] A total of 18,786 Red Army troops were deployed at strategically important locations within the country: Alytus, Prienai, Gaižiūnai, and Naujoji Vilnia.[6] This move effectively ended Lithuanian neutrality and brought it directly under Soviet influence.

Occupation and annexation

While Germany was conducting its military campaign in Western Europe in May and June 1940, the USSR invaded the Baltic states.[7] On 14 June 1940, an ultimatum was served to Lithuania on the alleged grounds of abduction of Red Army troops. The ultimatum said Lithuania should remove officials that the USSR found unsuitable (the Minister of the Interior and the Head of the Security Department in particular), replace the government, and allow an unlimited number of Red Army troops to enter the country. The acceptance of the ultimatum would have meant the loss of sovereignty, but Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov declared to diplomat Juozas Urbšys that, whatever the reply may be, "troops will enter Lithuania tomorrow nonetheless".[8] The ultimatum was a violation of every prior agreement between Lithuania and the USSR and of international law governing the relations of sovereign states.[9]

The last session of the government of the Republic of Lithuania was called to discuss the ultimatum,[9] with most members in favour of accepting it. On 15 June, President Antanas Smetona left for the West, expecting to return when the geopolitical situation changed,[10] leaving Prime Minister Antanas Merkys in Lithuania. Before his departure, Smetona transferred most presidential duties to Merkys. Under the constitution, the prime minister became acting president whenever the president was unable to carry out his duties.

Meanwhile, the 8th and 11th armies of the USSR, comprising a total of 15 divisions, crossed the border. Flying squads took over the airports of Kaunas, Radviliškis, and Šiauliai. Regiments of the Red Army disarmed the Lithuanian military, took over its assets, and supported local communists. On 16 June, Merkys announced in a national radio broadcast that he had deposed Smetona, and was now president in his own right. On 17 June, the cabinet resolved that Smetona had effectively abandoned his post by leaving the country and confirmed Merkys as president without any qualifiers.

Later that day, under pressure from Moscow, on 17 June 1940, Merkys appointed Justas Paleckis prime minister and resigned soon after. Paleckis then assumed presidential duties, and Vincas Krėvė was appointed prime minister.[11] The Communist Party was legalized again and began publication of its papers and staging meetings to support the new government. Opposition organizations and newspapers were outlawed, and ties abroad cut. On 14–15 July, elections took place for a "People's Seimas." The only contender was the Union of the Working People of Lithuania, a front for the Communists. Citizens were mandated to vote, and the results of the elections were likely falsified. At its first meeting on 21 July, the new People's Seimas declared that the Lithuanian people desired to join the Soviet Union. Accordingly, it unanimously changed Lithuania's official name to the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (LSSR) and formally petitioned to join the Soviet Union as a constituent republic. Resolutions to start the country's Sovietisation were passed the same day. On 3 August, a Lithuanian delegation of prominent public figures was dispatched to Moscow to sign the document by which Lithuania acceded to the USSR. After the signing, Lithuania was annexed to the USSR.[12] On 25 August 1940, an extraordinary session of the People's Seimas reorganized itself as the provisional Supreme Soviet of the LSSR, ratified the Constitution of the LSSR, which in form and substance was similar to the 1936 Constitution of the Soviet Union.

German invasion and the second Soviet occupation

On 22 June 1941, Nazi Germany invaded the USSR and occupied all of Lithuania within a month. The Lithuanian Activist Front (LAF), a resistance organisation founded in Berlin and led by Kazys Škirpa whose goal was to liberate Lithuania and re-establish its independence, cooperated with the Nazis. The LAF was responsible for killing many Lithuanian Jews (during the first days of the Holocaust in Lithuania).[13] Škirpa was named prime minister in the Provisional Government of Lithuania; however, the Germans placed him under house arrest and dissolved the LAF on 5 August 1941.[14][15] During the German occupation, Lithuania was made part of the Reichskommissariat Ostland. Between July and October 1944, the Red Army entered Lithuania once again, and the second Soviet government began. The first post-war elections took place in the winter of 1946 to elect 35 representatives to the LSSR Supreme Council. The results were again likely falsified to show an attendance rate of at over 90% and to establish an absolute victory for Communist Party candidates. The LSSR Supreme Council under Paleckis was formally the supreme governmental authority; in reality, power was in the hands of the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, a post held by Antanas Sniečkus until 1974.[16]

Red Army crimes

Upon recapturing Lithuania from the retreating Germans in 1944, the Red Army immediately began committing war crimes. The situation was so extreme that even Sniečkus complained to Lavrentiy Beria on 23 July that "If such robbery and violence continues in Kaunas, this will burst our last sympathy for the Red Army". Beria passed this complaint on to Joseph Stalin.[17]

In a special report on the situation in the Klaipėda Region, the head of the local NKGB operational group wrote that:

A beautiful city, Šilutė, left by the Germans without a battle, currently looks repulsive: there is not one remaining store, almost no flats that are suitable for living. ... Metal scrap collection teams are blowing up working agricultural machinery, engines of various kinds, stealing valuable equipment from the companies. There is no electricity in Šilutė because an internal combustion engine was blown up.[18]

In the same report, the mass rape of Lithuanian women in the Klaipėda and Šilutė regions was reported:

Seventy year old women and fourteen-year-old girls are being raped, even in the presence of parents. For example, in November 1944 eleven soldiers raped a Priekulė County resident in the presence of her husband. In Šilutė district, two soldiers, covering her head with a bag, at the doorway raped a seventy-year-old woman. On 10 December, two soldiers shot a passing elderly woman.[18]

In Klaipėda Lithuanian men aged 17 to 48 were arrested and deported. In December 1944, Chief of the Priekulė KGB Kazakov wrote to the LSSR Minister of the Interior Josifas Bertašiūnas that due to the soldiers' violence most of the houses in Priekulė were unsuitable for living in: windows were knocked out, fireplaces disassembled, furniture and agricultural inventory broken up and exported as scrap. Many Red Army soldiers engaged in robbery, rape, and murder, and Lithuanians who saw soldiers at night would often run from their homes and hide.[19]

"On the night of 20 October, aviation unit senior M. Kapylov, by taking revenge against 14-year-old Marija Drulaitė who refused to have sexual intercourse, killed her, her mother, uncle Juozas and severely injured a 12-year-old."

Other regions of the LSSR also suffered heavily. For example, on 26 December 1944, Kaunas' NKGB representative Rodionov wrote to the USSR and LSSR Ministers of the Interior that due to the violence and mass arrests by the counterintelligence units of SMERSH, many Kaunas inhabitants were forced into crime[clarification needed]. Eleven SMERSH subdivisions did not obey any orders, not even those from the NKGB.[22] Chief of the Vilnius Garrison, P. Vetrov, in his order described discipline violations: on 18 August a soldier went fishing with explosives in the Neris river; on 19 August a fifteen-minute firefight took place between the garrison soldiers and prison guards; on 22 August drunk officers shot at each other.[23] On 1 October 1944, Chief of the Kaunas NKVD G. Svečnikov reported that on the night of 19 October two aviation unit soldiers killed the Mavraušaitis family during a burglary.[20] On 17 January 1945, Chairman of the Alytus Executive Committee requested the LSSR People's Commissars Council to withdraw the border guards unit, which was sent to fight the Lithuanian partisans, because it was burning not only the enemy's homes and farms, but also those of innocent people. They were also robbing local inhabitants cattle and other property.[24]

Sovietisation

The Sovietisation of Lithuania began with the strengthening of the supervision of the Communist Party. Officials were sent from Moscow to set up bodies of local governance. They were exclusively Lithuanian, with trustworthy Russian specialists for assistants – it was these who were in effective control. By the spring of 1945, 6,100 Russian-speaking workers had been sent to Lithuania.[12] When the Soviets reoccupied the territory, Lithuanians were deprived of all property except personal belongings. This was followed by collectivisation, which started in 1947, with people being forced to join kolkhozes.[25] Well-off farmers would be exiled, and the livestock of the peasants from the surrounding areas would be herded to their properties. Since kolkhozes had to donate a large portion of their produce to the state, the people working there lived in poorer conditions than the rest of the nation. Their pay would often be delayed and made in kind and their movement to cities was restricted. This collectivisation ended in 1953.

Lithuania became home to factories and power plants, in a bid to integrate the country into the economic system of the USSR. The output of major factories would be exported from the republic as there was a lack of local demand. This process of industrialisation was followed by urbanisation, as villages for the workers had to be established or expanded in the vicinity of the new factories,[26] resulting in new towns such as Baltoji Vokė, Naujoji Akmenė, Elektrėnai and Sniečkus or expansion of old ones such as Jonava. Residents would be relocated from elsewhere in the LSSR, and from other USSR republics.[27] By 1979, more than half of population lived in urban areas.

All symbols of the former Republic of Lithuania were removed from public view by 1950, and the country had its history rewritten and its achievements belittled. The veneration of Stalin was spread and the role of Russia and the USSR in the history of Lithuania was highlighted. People were encouraged to join the Communist Party and communist organisations. Science and art based on communist ideology and their expression controlled by censorship mechanisms. People were encouraged into atheism in an attempt to secularise Lithuania, with monasteries closed, religion classes prohibited and church-goers persecuted.

Armed resistance

The second Soviet occupation was followed by armed resistance in 1944–1953, aiming to restore an independent Lithuania, re-establish capitalism and eradicate communism, and bring back national identity and freedom of faith. Partisans were labelled bandits by the Soviets. They were forced into the woods and into armed resistance by the Soviet rule. Armed skirmishes with the Red Army were common between 1944 and 1946. From the summer of 1946 a partisan organisational structure was established, with units of 5–15 partisans living in bunkers. Guerrilla warfare with surprise attacks was the preferred tactic. In 1949 the Union of Lithuanian Freedom Fighters under Jonas Žemaitis–Vytautas was founded. Partisan units became smaller still, consisting of 3 to 5 partisans. Open fighting was a rarity, with sabotage and terrorism preferred. Despite guerrilla warfare failing to achieve its objectives and claiming the lives of more than 20,000 fighters, it demonstrated to the world that Lithuania's joining the USSR had not been a voluntary act and highlighted the desire of many Lithuanians to be independent.[28]

Deportations

In the fall of 1944, lists of 'bandits' and 'bandit family' members to be deported appeared. Deportees were marshaled and put on a USSR-bound trains in Kaunas in early May 1945, reaching their destination in Tajikistan in summer. Once there, they employed as forced labour at cotton plantations.[29] In May 1945, a new wave of deportations from every county took place, enforced by battlegroups made of NKVD and NKGB staff and NKVD troops – the destruction battalions, or istrebitels. On 18–21 February 1946, deportations began in four counties: Alytus, Marijampolė, Lazdijai, and Tauragė.

On 12 December 1947 the Central Committee of the Lithuanian Communist Party resolved that actions against supporters of resistance were too weak and that additional measures were in order.[30] A new series of deportations began and 2,782 people were deported in December. In January–February 1948, another 1,134 persons[31] were exiled from every county in Lithuania. By May 1948, the total number of deportees had risen to 13,304. In May 1948, preparations for very large-scale deportations were being made, with 30,118 staff members from Soviet organisations involved.[32] On 22–23 May 1948, a large-scale deportation operation called Vesna began, leading to 36,932 arrests, a figure that later increased to 40,002.

The second major mass deportation, known as Operation Priboi, took place on 25–28 March 1949, during which the authorities put 28,981 persons into livestock cars and dispatched them deep into the USSR. Some people went into hiding and managed to escape the deportations, but then a manhunt began in April. As a result, another two echelons left for the remote regions of the USSR. During March–April 1949, a total of some 32,000 people were deported from Lithuania. By 1952, 10 more operations had been staged, but of a smaller scale. The last deportations took place in 1953, when people were deported to the district of Tomsk and the regions of Altai and Krasnoyarsk.[33]

Dissident movement

Even after the guerrilla resistance had been quelled, Soviet authorities failed to suppress the movement for Lithuania's independence. Underground dissident groups had been active from the 1950s, publishing periodicals and Catholic literature.[34] They fostered national culture, celebrated historical events, instigated patriotism and encouraged hopes for independence. In the 1970s, dissidents established the Lithuanian Liberty League under Antanas Terleckas. Founded in Vilnius in the wake of an international conference in Helsinki, Finland, which recognised the borders established after the Second World War, the Lithuanian Helsinki Group demanded that Lithuania's occupation be recognised as illegal and the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact be condemned.[35] The dissidents ensured that the world would receive information about the situation in the LSSR and human rights violations, which caused Moscow to soften the regime.[36] In 1972, young Romas Kalanta immolated himself in Kaunas in a public display of protest against the regime. This was followed by public unrest, demonstrating that a large portion of the population were against the regime.[37]

The Catholic Church took an active part in opposing the Soviets. The clergy published chronicles of the Catholic Church of Lithuania, secretly distributed in Lithuania and abroad. The faithful would gather in small groups to teach their children religion, celebrate religious holidays, and use national and religious symbols. The most active repressed figures of the movement were Vincentas Sladkevičius, Sigitas Tamkevičius, and Nijolė Sadūnaitė.[38]

Collapse of Soviet rule

In the 1980s, the USSR sank into a deep economic crisis. In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev was elected head of the USSR's Communist party and undertook internal reforms which had the effect of liberalising society (whilst actually increasing the economic chaos) and a new approach to foreign policy that effectively ended the Cold War. This encouraged the activity of anti-communist movements within the USSR, the LSSR included.[39] On 23 August 1987, the Lithuanian Liberty League initiated an unsanctioned meeting in front of the monument to Adomas Mickevičius in Vilnius. At the meeting, the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact was condemned for the first time in public. The meeting and the speeches made at it were widely reported by western radio stations. Also meeting was reported by Central Television and even TV Vilnius.

In May 1987, the Lithuanian Cultural Fund was established to engage in environmental activity and the protection of Lithuanian cultural assets. On 3 June 1988, the Lithuanian Reformation Movement (LRM) was founded; its mission was to restore the statehood of Lithuania; LRM supporters formed groups across Lithuania. On 23 August 1988, a meeting took place at Vingis Park in Vilnius, with a turnout of about 250,000 people. On 23 August 1989, marking 50 years of the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact and aiming to draw the world's attention to the occupation of the Baltic states, the Baltic Way event was staged.[40] Organised by the Lithuanian Reformation Movement, the Baltic Way was a chain of people holding hands that stretched for nearly 600 kilometres (370 mi) to connect the three Baltic capitals of Vilnius, Riga, and Tallinn. It was a display of the aspiration of the Lithuanian, Latvian, and Estonian people to part ways with the USSR. The LSSR de facto ceased to exist on 11 March 1990, with the Reconstituent Seimas declaring Lithuania's independence restored. It took the line that since Lithuania's membership in the USSR was a violation of international law, it was reasserting an independence that still legally existed. Therefore, the Reconstituent Seimas argued that Lithuania did not need to follow the formal procedure of secession from the USSR.

Independence restored

Lithuania declared the sovereignty of its territory on 18 May 1989 and declared independence from the Soviet Union on 11 March 1990 under its pre-1940 name, the Republic of Lithuania. Lithuania was the first Baltic state to assert state continuity, and the first Soviet Republic to declare full independence from the Union (though Estonia was the first Soviet Republic to assert its national sovereignty and the supremacy of its national laws over the laws of the Soviet Union). All of the Soviet Union's claims on Lithuania were repudiated as Lithuania declared the restitution of its independence. The Soviet Union claimed that this declaration was illegal, as Lithuania had to follow the process of secession mandated in the Soviet Constitution if it wanted to leave.

Lithuania contended that it did not need to follow the process of secession because the entire process by which Lithuania joined the Soviet Union violated both Lithuanian and international law. Specifically, it contended that Smetona never resigned, making Merkys' takeover of the presidency illegal and unconstitutional. Therefore, Lithuania argued that all acts leading up to the Soviet takeover were ipso facto null and void, and it was simply reasserting an independence that still existed under international law.

The Soviet Union threatened to invade, but the Russian SFSR's declaration of sovereignty on 12 June meant that the Soviet Union could not enforce Lithuania's retention. While other republics held the union-wide referendum in March to restructure the Soviet Union in a loose form, Lithuania, along with Estonia, Latvia, Armenia, Georgia, and Moldova did not take part. Lithuania held an independence referendum earlier that month, with 93.2% voting for it.

Iceland immediately recognised Lithuania's independence. Other countries followed suit after the failed coup in August, with the State Council of the Soviet Union recognising Lithuania's independence on 6 September 1991. The Soviet Union officially ceased to exist on 26 December 1991.

It was agreed that the Soviet Army (later the Russian Army) must leave Lithuania because it was stationed without any legal reason. Its troops withdrew in 1993.[41]

Politics

First secretaries of the Communist Party of Lithuania

The first secretaries of the Communist Party of Lithuania were:[42]

- Antanas Sniečkus, 1940–1941; 1944–1974

- Petras Griškevičius, 1974–1987

- Ringaudas Songaila, 1987–1988

- Algirdas Brazauskas, 1988–1989

Economy

Collectivization in the Lithuanian SSR took place between 1947 and 1952.[43] The 1990 per capita GDP of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic was $8,591, which was above the average for the rest of the Soviet Union of $6,871.[44] This was half or less of the per capita GDPs of adjacent countries Norway ($18,470), Sweden ($17,680) and Finland ($16,868).[44] Overall, in the Eastern Bloc, systems without competition or market-clearing prices became costly and unsustainable, especially with the increasing complexity of world economics.[45] Such systems, which required party-state planning at all levels, collapsed under the weight of accumulated economic inefficiencies, with various attempts at reform merely contributing to the acceleration of crisis-generating tendencies.[46]

Lithuania accounted for 0.3 percent of the Soviet Union's territory and 1.3 percent of its population, but it generated a significant amount of the Soviet Union's industrial and agricultural output: 22 percent of its electric welding apparatus, 11.1 percent of its metal-cutting lathes, 2.3 percent of its mineral fertilizers, 4.8 percent of its alternating current electric motors, 2.0 percent of its paper, 2.4 percent of its furniture, 5.2 percent of its socks, 3.5 percent of underwear and knitwear, 1.4 percent of leather footwear, 5.3 percent of household refrigerators, 6.5 percent of television sets, 3.7 percent of meat, 4.7 percent of butter, 1.8 percent of canned products, and 1.9 percent of sugar.[47]

Lithuania was also a net donor to the USSR budget.[48] It was calculated in 1995 that the occupation resulted in 80 billion LTL (more than 23 billion euros) worth of losses, including population, military, and church property losses and economic destruction among other things.[49] Lithuania mostly suffered until 1958 when more than a half of the annual national budgets was sent to the USSR budgets, later this number decreased but still remained high at around 25% of the annual national budgets until 1973 (totally, Lithuania sent about one third of all its annual national budgets money to the USSR budgets during the whole occupation period).[50]

In astronomy

A minor planet, 2577 Litva, discovered in 1975 by a Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh is named after the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic.[51]

See also

References

- ^ "Закон о принятии Литовской Советской Социалистической Республики в Союз Советских Социалистических Республик. от 3 августа 1940 года".

- ^ Ronen, Yaël (2011). Transition from Illegal Regimes Under International Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-521-19777-9.

- ^ Šepetys N., Molotovo – Ribbentropo paktas ir Lietuva, Vilnius, 2006.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (2004). The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999. Yale University Press. pp. 62–63. ISBN 0-300-10586-X.

- ^ "Å altiniai".

- ^ Lithuania in 1940–1990. A History of Lithuania under Occupation, ed. Anušauskas A., Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania, Vilnius, 2007.

- ^ Christie, Kenneth, Historical Injustice and Democratic Transition in Eastern Asia and Northern Europe: Ghosts at the Table of Democracy, RoutledgeCurzon, 2002, ISBN 0-7007-1599-1

- ^ Urbšys J., Lietuva lemtingaisiais 1939–1940 metais, Tautos fondas, 1988.

- ^ a b Audėnas J., Paskutinis posėdis, Vilnius, 1990.

- ^ Eidintas, A. Antanas Smetona and His Lithuania, Brill/Rodopi, 2015.

- ^ Senn A. E., Lithuania 1940– Revolution from Above, Rodopi, 2007.

- ^ a b Breslavskienė L, Lietuvos okupacija ir aneksija 1939-1940: dokumentų rinkinys, Vilnius: Mintis, 1993.

- ^ Timothy Snyder - Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, ch.6-Final Solution. 2012. ISBN 978-0-465-0-3147-4

- ^ Jegelevičius, Sigitas (11 June 2004). "1941 m. Lietuvos laikinosios vyriausybės atsiradimo aplinkybės". Voruta (in Lithuanian). 11 (557). ISSN 1392-0677. Archived from the original on 7 May 2006.

- ^ Burauskaitė, Teresė Birutė (5 January 2016). "Kazio Škirpos veiklą Antrojo pasaulinio karo metais" (PDF). Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ "XXI amžius". Xxiamzius.lt.

- ^ a b "Raudonosios armijos nusikaltimai Lietuvoje: žmogžudystės, prievartavimai, plėšimai". 15min.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ a b Kuzmin. "Klaipėdos NKGB operatyvinės grupės viršininko spec. pranešimas NKGB liaudies komisarui A. Guzevičiui apie padėtį Klaipėdos krašte". Kgbveikla.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ "NKVD operatyvinės grupės aiškinamasis raštas NKVD liaudies komisarui J. Bartašiūnui apie padėtį Priekulės valsčiuje (Mėmelio krašte)". Kgbveikla.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ a b "1944 m. rugsėjo 26–30 d. Kauno m. NKVD skyriaus operatyvinės veiklos suvestinė". Kgbveikla.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ Petrov, Nikita (2010). Кто руководил органами госбезопасности: 1941-1954. Moscow: Звенья. ISBN 978-5-7870-0109-9. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ "Kauno operatyvinio sektoriaus viršininko pranešimas NKVD liaudies komisarui J. Bartašiūnui apie SMERŠ-o savivaliavimą Kaune". Kgbveikla.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ "Vilniaus įgulos viršininko įsakymas Nr. 13 dėl drausmės pažeidimų". Kgbveikla.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ "Alytaus apskrities Vykdomojo komiteto skundas Lietuvos SSR liaudies komisarų tarybai apie neteisėtus pasieniečių veiksmus". Kgbveikla.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ The History of the SSR of Lithuania, vol. 4, Vilnius, 1947.

- ^ Grybkauskas S., Sovietinė nomenklatūra ir pramonė Lietuvoje 1965-1985 metais / Lietuvos istorijos institutas. – Vilnius: LII leidykla, 2011.

- ^ Epochas jungiantis nacionalizmas: tautos (de)konstravimas tarpukario, sovietmečio ir posovietmečio Lietuvoje / Lietuvos istorijos institutas. – Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos instituto leidykla, 2013

- ^ Gailius B., Partizanai tada ir šiandien, Vilnius, 2006.

- ^ Lithuania in 1940–1990, ed. A. Anušauskas, Vilnius: GRRCL, 2005, p. 293.

- ^ Lietuvos sovietizacija 1944–1947 m.: VKP(b) CK dokumentai, sud. M. Pocius, Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos institutas, 2015, p. 126.

- ^ Tremtis prie Mano upės, sud. V. G. Navickaitė, Vilnius: Lietuvos nacionalinis muziejus, 2008, p. 7.

- ^ Lietuvos gyventojų trėmimai 1941, 1945–1952 m., Vilnius, 1994, p. 210.

- ^ Lietuvos kovų ir kančių istorija. Lietuvos gyventojų trėmimai 1940–1941; 1944–1953 m. Sovietinės okupacija valdžios dokumentuose, red. A. Tyla, Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos institutas, 1995, p. 101

- ^ V. Vasiliauskaitė, [null Lietuvos Ir Vidurio Rytų Europos šalių periodinė savivalda], 1972–1989, 2006.

- ^ Lietuvos Helsinkio grupė (dokumentai, atsiminimai, laiškai), sudarė V. Petkus, Ž. Račkauskaitė, . Uoka, 1999.

- ^ Tininis V., Sovietinė Lietuva ir jos veikėjai, Vilnius, 1994.

- ^ Bagušauskas J. R., [null Lietuvos jaunimo pasipriešinimas sovietiniam režimui ir jo slopinimas], 1999.

- ^ "Neginkluotas antisovietinis pasipriešinimas 1954-1988 m." Genocid.lt.

- ^ Ivanauskas V., Lietuviškoji nomenklatūra biurokratinėje sistemoje. Tarp stagnacijos ir dinamikos (1968-1988 m.), Vilnius, 2011.

- ^ Anušauskas A., Kelias į nepriklausomybę – Lietuvos sąjūdis, Kaunas, 2010.

- ^ Saldžiūnas, Vilius. "Paskutiniai Rusijos kariai iš Lietuvos gėdingai traukėsi nakties tyloje: jie jau buvo virtę nevaldoma ir mirtinai pavojinga gauja". DELFI (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ "07636". Knowbysight.info.

- ^ O'Connor 2003, p. xx–xxi

- ^ a b Maddison 2006, p. 185

- ^ Hardt & Kaufman 1995, p. 1

- ^ Hardt & Kaufman 1995, p. 10

- ^ "Structure of the Economy". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ Orlowski, Lucjan T. "Direct transfers between the former Soviet Union central budget and the republics: Past evidence and current implications" (PDF). Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ Tracevičiūtė, Roberta (1 April 2019). "Maskvai nepatiks: surinkti įrodymai, kad Lietuva buvo SSRS donorė". 15min.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ Tracevičiūtė, Roberta. "Paneigtas Kremliaus transliuojamas mitas: kada išrašysime sąskaitą Rusijai?". 15min.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ ""2577 Litva" - Google Search". Google.com.

Bibliography

- Hardt, John Pearce; Kaufman, Richard F. (1995). East-Central European Economies in Transition. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 1-56324-612-0.

- Maddison, Angus (2006). The world economy. OECD Publishing. ISBN 92-64-02261-9.

- O'Connor, Kevin (2003). The history of the Baltic States. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-32355-0.

External links

- 1940 Constitution of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic

- 1978 Constitution of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic

- Lithuania: An Encyclopedic Survey – a 1986 English-language Soviet work.