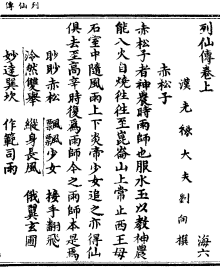

Liexian Zhuan

| Liexian Zhuan | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 列仙傳 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 列仙传 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Biographies of Exemplary Immortals | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

The Liexian Zhuan, sometimes translated as Biographies of Immortals, is the oldest extant Chinese hagiography of Daoist xian "transcendents; immortals; saints; alchemists". The text, which compiles the life stories of about 70 mythological and historical xian, was traditionally attributed to the Western Han dynasty editor and imperial librarian Liu Xiang (77–8 BCE), but internal evidence dates it to the 2nd century CE during the Eastern Han period. The Liexian Zhuan became a model for later authors, such as Ge Hong's 4th century CE Shenxian zhuan ("Biographies of Divine Immortals").

Title

Liexian Zhuan combines three words:

- liè (列, "rank; array; order; line up; list")

- xiān (仙, "transcendent being; celestial being; 'immortal'")

- zhuàn (傳, " tradition; biography; commentary on a classic (e.g., Zuozhuan)"(—cf. chuàn (傳, "transmit; pass along; hand down; spread")

The compound lièzhuàn (列傳, lit. "arrayed lives") is a Classical Chinese term meaning "[non-imperial] biographies". The Liexian Zhuan follows the liezhuan biographical format of traditional Chinese historiography, which was established by Sima Qian in his c. 94 BCE Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian). Many later texts adopted the liezhuan format, for example, the Daoist Shenxian zhuan and the Buddhist Gaoseng zhuan (Memoirs of Eminent Monks).[1]

There is no standard translation of Liexian Zhuan, and renderings include:

- A Gallery of Chinese Immortals[2]

- Biographies of the Many Immortals[3]

- Biographies of Illustrious Genii[4]

- Collections of the Biographies of the Immortals[5]

- Immortals' Biographies[6]

- Arrayed Lives of Transcendents[7]

- Biographies of the Immortals[8]

- Biographies of Exemplary Immortals[9]

- Biographies of Immortals[10][11]

- Arrayed Traditions of Transcendents[12]

- Traditions of Exemplary Transcendents[13]

- Biography of the Immortal Deities[14]

- Lives of the Immortals[15]

The difficulty of translating this title is demonstrated by Campany's three versions. Note the modern shift to translating xian as "transcendent" rather than "immortal"; Daoist texts describe xian as having extraordinary "longevity" or "long life" but not eternal "immortality" as understood in Western religions.[16][17]

Liu Xiang

The traditional attribution of the Liexian Zhuan to the Western Han scholar Liu Xiang is regarded as dubious, and modern scholars generally believe it was compiled during the Eastern Han (25-220 CE).[18] There are two kinds of evidence that Liu was not the compiler.

First, the Liexian Zhuan was not listed in Ban Gu's 111 CE Book of Han Yiwenzhi ("Treatise on Literature") imperial bibliography, and the 636 Book of Sui was the first official dynastic history to record it bibliographically. However, the Yiwenzhi does list many works written and compiled by Liu Xiang, including two with similar titles: Lienǚ Zhuan (列女傳, Biographies of Exemplary Women) and Lieshi zhuan (列士傳, Biographies of Exemplary Officials).

Second, some sections of the Liexian Zhuan refer to events after Liu Xiang's death in 8 or 6 BCE. Eastern Han historical books dating from the early 2nd century CE cite a version (or versions) of the hagiography. Internal evidence shows that some sections of the text were added in the 2nd century, and later editing occurred.[18] The hagiography contains some phrases dating from the Jin dynasty (266–420), but remains the oldest surviving collection of Taoist hagiography.[11]

The attribution of the Liexian zhuan to Liu Xiang occurred relatively early, and it was accepted by the Eastern Jin Daoist scholar Ge Hong.[18] Ge's c. 330 Baopuzi describes how Liu redacted his Liexian Zhuan in a context explaining the reason Liu failed to produce an alchemical gold elixir using the private method of Liu An was because no teacher had transmitted the necessary oral explanations to him.

As for his compilation (撰) of Liexian zhuan, he revised and extracted (自刪…出) passages from the book by the Qin grandee Ruan Cang 阮倉, and in some cases [added] things he had personally seen (或所親見), and only thus (然後) came to record (記) it. It is not an unwarranted fabrication ([or "fiction"] 非妄言也).[19]

Ge Hong uses ranhou (然後, "only thus") to emphasize that the veracity of Liexian Zhuan biographies is not tainted by Liu Xiang's failure in waidan alchemy, indicating that the collected stories are reliable because he could not have invented them.[20] Internal evidence suggests that Liu compiled the Liexian zhuan in the very last years of his life. Although his authorship is disputed and the text is dated later than the 1st century BCE, "recent scholars have argued cogently" for the traditional attribution.[21] He concludes that the ascription to Liu Xiang is "not wholly incredible, but the text we have today contains later accretions and has also dropped some passages".[22]

Since Liu Xiang was an orthodox Confucianist and not a Daoist, his Liexian Zhuan depiction of transcendents' lives represents knowledge from general Han culture rather than a specific religious community. In subsequent generations, his hagiography became widely known as a source for literary allusion among educated Chinese of later periods.[18]

From a higher perspective, the question of Liu Xiang's authorship "is irrelevant", because the received text is not the original. The Liexian Zhuan was transmitted in diverse manuscript copies for ten centuries, until the Song dynasty 1019 Daoist Canon incorporated a standard edition.[23]

Textual versions

The Liexian Zhuan exists in many, sometimes dissimilar, versions. For instance, the original text likely contained 72 hagiographies, yet the standard version has 70, and others have 71. The c. 1029 Daoist encyclopedia Yunji Qiqian includes 48 hagiographies.[21]

Two Tang dynasty leishu Chinese encyclopedias, the 624 Yiwen Leiju and 983 Taiping Yulan extensively quote from the Liexian Zhuan.[11] Analysis of Liexian zhuan citations preserved in these and other old sources shows that some portions of the original text have been lost from all surviving versions.[18]

The earliest extant version of the Liexian Zhuan is from the Ming dynasty 1445 Zhengtong daozang (正統道藏, "Daoist Canon of the Zhengtong Era, 1436-1450"). Several other Ming and Qing editions of the text were published, including two jiàozhèng (校正, "corrected; rectified") versions.[24]

Liexian Zhuan is also the title of a different Yuan dynasty (1206-1368) collection of 55 xian biographies, including the popular Eight Immortals, with woodcut illustrations.[25]

Content

The present Daoist canonical Liexian Zhuan, which is divided into two chapters, comprises about 70 "tersely worded" hagiographies of transcendents.[22] In many cases, the Liexian Zhuan is the only early source referring to an individual transcendent.[26] The collection does not offer anything resembling a full biography, but only a few informative anecdotes about each person. The briefest entries have fewer than 200 characters.[18]

Employing the traditional liezhuan ("arrayed lives") biographical arrangement, the Liexian Zhuan arranges its Daoist hagiographies in roughly chronological order, starting with the mythological figure Chisongzi who was Rain Master for the culture hero Shennong (mythically dated to the 28th century BCE), and ending with the Western Han herbalist and fangshi Xuan Su 玄俗. They include individuals "of every rank and station, ranging from purely mythical beings to hermits, heroes, and men and women of the common people".[27] The collection includes mythic personages (e.g., Yellow Emperor and Pengzu who allegedly lived over 800 years), famous Daoists (Laozi and Yinxi the Guardian of the Pass), and historical figures (Anqi Sheng who instructed Qin Shi Huang (r. 247-220 BCE) and Dongfang Shuo the court jester for Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141–87 BCE)).[28]

The standard format for Liexian zhuan entries is to give the subject's name, sometimes style name, usually native place (or the formulaic "No one knows where he came from"), and often the period in which he or she supposedly lived. Sometime after the 330s, the text was appended with sets of laudatory zàn (贊, "encomia") that are rhymed hymns praising the recorded xian.[29] Some editions include an old preface, of uncertain authorship and date, that is not included in the Daoist canonical edition.[24]

Two sample hagiographies illustrate some common themes in the Liexian Zhuan. First, many stories focus on the supernatural techniques of transcendents and how they acquired them.[21] Mashi Huang (馬師皇) was a legendary equine veterinarian during the Yellow Emperor's reign.

...a horse doctor in the time of the Yellow Emperor. He knew the vital symptoms in a horse's constitution, and on receiving his treatment the animal would immediately get well. Once a dragon flew down and approached him with drooping ears and open jaws. Huang said to himself: "This dragon is ill and knows that I can effect a cure." Thereupon he performed acupuncture on its mouth just below the upper lip, and gave it a decoction of sweet herbs to swallow, which caused it to recover. Afterwards, whenever the dragon was ailing, it issued from its watery lair and presented itself for treatment. One morning the dragon took Huang on its back and bore him away[30]

Second, hagiographies often didactically represent xian using their transcendental powers to support the poor and helpless.[11] Chang Rong (昌容) was able to maintain the appearance of a young woman for two centuries by only eating Rubus crataegifolius (Korean raspberry) roots:

Chang Rong was a follower of the Dao from Mount Chang (Changshan 常山; i.e., the Hengshan, Shanxi). She called herself the daughter of the King of Yin (Yinwang nǚ 殷王女) and ate roots of rubus (penglei 蓬虆). She would come and go, ascending and descending. People saw her for some two hundred years yet she always looked about twenty. When she was able to get purple grass she sold it to dyers and gave the proceeds to widows and orphans. It was like this for generations. Thousands came to make offerings at her shrine.[31]

Researchers have found evidence of anti-inflammatory effects from R. crataegifolius root extracts.[32]

Third, like the above "decoction of sweet herbs" and "roots of rubus", about half the transcendents described in the Liexian Zhuan had powers that ultimately came from drugs. For instance, after Master Redpine took a drug called shuiyu (水玉, "liquid jade") denoting quartz crystals in solution,[33] he transformed himself by fire, and ascended to Mount Kunlun where he lived with the Queen Mother of the West. The text mentions many herbal and mineral drugs, including pine nuts, pine resin, China root, fungus, Chinese angelica, cinnabar powder, and mica.[34]

Translations

There are no full English translations of the text analogous to the French critical edition and annotated translation Le Lie-sien tchouan by Kaltenmark.[35][28] Giles translated eight Liexian Zhuan entries,.[2] and Campany's annotated translation of the Shenxian Zhuan frequently cites the Liexian Zhuan.[12]

References

- Campany, Robert Ford (1996). Strange Writing: Anomaly Accounts in Early Medieval China. Albany NY: SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791426593.

- Campany, Robert Ford (2002). To Live As Long As Heaven and Earth: Ge Hong's Traditions of Divine Transcendents. contribution by Hong Ge. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520230347.

- Campany, Robert Ford (2009). Making Transcendents: Ascetics and Social Memory in Early Medieval China. University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 9780824833336.

- Giles, Lionel (1979) [1948]. A Gallery of Chinese Immortals. London / New York City: John Murray / AMS Press (reprint). ISBN 0-404-14478-0.

- Kohn, Livia, ed. (1989). Taoist Meditation and Longevity Techniques. University of Michigan Center for Chinese studies. ISBN 9780892640850.

- Pas, Julian; Leung, Man Kam (1998). Historical Dictionary of Taoism. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810833692.

- Penny, Benjamin (2008). "Liexian zhuan 列仙傳 Biographies of Exemplary Immortals". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Taoism. Two volumes. Routledge. pp. 653–654. ISBN 9780700712007.

- Alchemy, Medicine and Religion in the China of A.D. 320: The Nei Pien of Ko Hung. Translated by Ware, James R. MIT Press. 1966. ISBN 9780262230223.

- Wu, Lu-Ch'iang and Davis, Tenney L. (1934). "Ko Hung (Pao P'u Tzu), Chinese Alchemist of the Fourth Century", Journal of Chemical Education, pp. 517–20.

Footnotes

- ^ Campany 1996, p. 25.

- ^ a b Giles 1979.

- ^ Chan, Wing-Tsit. (1963). The Way of Lao Tzu, Bobbs-Merrill.

- ^ Ware 1966.

- ^ Needham, Joseph; et al. (1986). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 6 Biology and Biological Technology, Part 1: Botany. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521087315.

- ^ Kohn 1989.

- ^ Campany 1996.

- ^ Eskildsen, Stephen (1998). Asceticism in Early Taoist Religion. Albany NY: SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-3955-0.

- ^ Penny 2008.

- ^ Pas & Leung 1998.

- ^ a b c d Theobald, Ulrich (2010), Liexianzhuan 列仙傳 "Biographies of Immortals", Chinaknowledge.

- ^ a b Campany 2002.

- ^ Campany 2009.

- ^ Yap, Joseph P. (2016). Zizhi Tongjian, Warring States and Qin, CreateSpace.

- ^ Strickmann, Michel and Anna K. Seidel (2017), "Daoism", Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Bokenkamp, Stephen R. (1997). Early Daoist Scriptures. University of California Press. pp. 21-3. ISBN 9780520923126.

- ^ Campany 2002, pp. 4-5; Campany 2009, pp. 33-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Penny 2008, p. 653.

- ^ Tr. Campany 2002, p. 104, emending Ware 1966, p. 51.

- ^ Campany 2002, p. 104.

- ^ a b c Campany 1996, p. 41.

- ^ a b Campany 2009, p. 7.

- ^ Pas & Leung 1998, p. 55.

- ^ a b Campany 1996, pp. 40–1.

- ^ Giles 1979, p. 11.

- ^ Pas & Leung 1998, p. 56.

- ^ Giles 1979, p. 13.

- ^ a b Penny 2008, p. 654.

- ^ Penny 2008, pp. 653–4.

- ^ Tr. Giles 1979, p. 13.

- ^ Tr. .Penny 2008, p. 654.

- ^ Cao Y., Wang Y., Jin H., Wang A., Liu M., and Li X. (1996), "Anti-inflammatory effects of alcoholic extract of roots of Rubus crataegifolius", Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi (China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica) 21.11: 687-688.

- ^ Campany 2002, p. 230.

- ^ Kohn 1989, p. 76.

- ^ Kaltenmark, Max, tr. (1953). Le Lie-sien tchouan: Biographies légendaires des immortels taoïstes de l'antiquité. Beijing: Université de Paris, Publications du Centre d'études sinologiques de Pékin. 1987 reprint Paris: Collège de France.

Further reading

- Kohn, Livia. (1998). God of the Dao, Lord Lao in History and Myth, Center for Chinese Studies, The University of Michigan.

External links

- Liexian Zhuan full text at the Chinese Text Project (in Chinese)