Pelagius of Oviedo

Pelagius (or Pelayo) of Oviedo (died 28 January 1153) was a medieval ecclesiastic, historian, and forger who served the Diocese of Oviedo as an auxiliary bishop from 1098 and as bishop from 1102 until his deposition in 1130 and again from 1142 to 1143. He was an active and independent-minded prelate, who zealously defended the privileges and prestige of his diocese. During his episcopal tenure he oversaw the most productive scriptorium in Spain, which produced the vast Corpus Pelagianum,[1] to which Pelagius contributed his own Chronicon regum Legionensium ("chronicle of the Kings of León"). His work as a historian is generally reliable, but for the forged, interpolated, and otherwise skilfully altered documents that emanated from his office he has been called el Fabulador ("the Fabulist")[2] and the "prince of falsifiers".[3] It has been suggested that a monument be built in his honour in Oviedo.[4]

Life

The date and place of Pelagius' birth are unknown. The Liber testamentorum includes a genealogy that suggests that Pelagius may have been related to the western Asturian families that founded the monasteries of Coria and Lapedo. He also made a donation to his own canons of properties he owned in Villamoros and Trobajuelo, near León, suggesting perhaps a Leonese connexion.[5]

The earliest known reference to Pelagius is as a deacon at Oviedo in 1096. He was an archdeacon there in 1097. His consecration as the auxiliary of bishop Martin I took place on 29 December 1098.[6] He succeeded Martin four years later, as the choice of Alfonso VI,[7] and with vigour took up the defence of his church's properties and jurisdictions. The Archbishop of Toledo (1086), Bernard de Sedirac, sought to incorporate the sees of Oviedo, León, and Palencia into his province as suffragans. In 1099 Pope Urban II gave the order. In 1104, Pelagius of Oviedo and Peter of León went to Rome to plead their case to the new pope, Paschal II, who granted them a privilege of exemption and made them dependent directly on Rome (1105).[8] At the same time (1104), Pelagius engaged in lawsuits with the count Fernando Díaz, the countess Enderquina Muñoz, and the abbot of Corias to maintain his rights of seignory within Asturias.[9] He was also involved in jurisdictional battles with the neighbouring sees of Burgos (over Asturias de Santillana) and Lugo, and between 1109 and 1113 had to fight off the metropolitan claims of the Archdiocese of Braga as well.[9] In 1121 the Archdiocese of Toledo successfully petitioned Pope Callistus II to remove Paschal's 1105 exemption, though this was regained in 1122.[8]

Pelagius was generally on good terms with Alfonso VI (died 1109) and his successor, Urraca (died 1126). After 1106 no new Count of Asturias was appointed and it seems that the title lapsed, while a castellan, a novus homo, with lesser authority replaced the last count. This was probably in the interests of Pelagius and his authority, since the county of Asturias corresponded to the centre of his diocese.[10] The bishop gave Urraca political support against both her husband, Alfonso the Battler of Aragon, and her son, the future Alfonso VII, who was in conflict with his mother after 1110. She in turn made grants to Oviedo on three separate occasions, in 1112, 1118, and 1120 and Pelagius was the dominant Asturian at court, confirming fifteen royal charters during her reign.[11] Pelagius had a part in reconciling the queen and her son at a council of the realm in Sahagún (1116). After Alfonso's accession he never recovered his importance, rarely appearing at the new king's court and never receiving a gift from him.[12]

In 1130 Pelagius was deposed by a synod held under Cardinal Humbert at Carrión, along with Diego and Munio, bishops of León and Salamanca, and the abbot of Samos, because they had opposed the marriage of Alfonso VII and Berenguela of Barcelona (1127) on grounds of consanguinity. Their deposition was politically motivated, engineered by Alfonso and the prelate Diego Gelmírez.[13] During the last decades of the eleventh century and the first of the twelfth, Santiago de Compostela became one of the leading centres of pilgrimage among the Catholic faithful, aided by the efforts of its archbishop, Diego Gelmírez. The rivalry between Pelagius and Diego can be seen in the former's attempt to establish Oviedo as a comparable destination for pilgrims, by expanding the cult of the relics of the Cathedral of San Salvador, most importantly the alleged Sudarium of Christ.[14] He has even been credited with the creation of the Arca Santa to house his cathedral's relics.[15]

Pelagius continued to live in Oviedo and be addressed as bishop. When his successor, Alfonso, died in January 1142, Pelagius took up the diocesan administration again until early in the summer of 1143.[16] By June the see was being administered by Froila Garcés, the archdeacon, and in September Martin II was elected bishop at a council in Valladolid. He had planned his own funeral and had reserved a space in the Cathedral of San Salvador for his burial. Nevertheless, his death came unexpectedly while he was visiting Santillana del Mar, and there he was buried.

Corpus Pelagianum

Among Pelagius writings is a short treatise on the origins of the cities of León, Oviedo, Toledo, and Zaragoza in 1142.[17] In the sixteenth century Ambrosio de Morales discovered a manuscript titled "Many Genealogies of the Scripture until Our Lady and Saint Anne", a genealogy of the Virgin Mary and Saint Anne ascribed to Pelagius, in the cathedral library of Oviedo. It contained several historical texts under the heading "Itacius", after the first of them, the chronicle by Hydatius. This manuscript has since been lost, but it demonstrates an especial interest of Pelagius' in the extended family of Jesus and his maternal grandmother.[18]

Liber chronicorum

Pelagius' original Chronicon[19] was composed as a continuation of a series of chronicles which he gathered together and had copied into the Liber chronicorum, the principal part of the Corpus Pelagianum. These included the Historia Gothorum of Isidore, the Chronica ad Sebastianum, and the Chronicon of Sampiro (which was heavily interpolated, but ultimately truncated).[20] Altogether these form the Liber chronicorum ("Book of Chronicles") which was finalised in 1132, when its preface, with an index, was composed.

Pelagius' original chronicle, that known as Chronicon regum Legionensium, was completed sometime after 1121, since it refers to the marriage of Alfonso VI's daughter Sancha to Rodrigo González, who is given the title Count.[21] The Chronicon can be found in twenty-four manuscripts, the earliest dating to the late twelfth century.[22] It begins with the rise of Vermudo II in 982 and ends with the death of Alfonso VI in 1109. Pelagius' work as a historian has been contrasted with that of the contemporary anonymous authors of the Historia seminense and the Chronica Adefonsi imperatoris. Pelagius' Latin is "unsophisticated and workmanlike ... [lacking] the verve and the rhetorical flourishes" of the Historia, and he does not display the "conspicuous erudition" of either.[22] Pelagius probably drew up his history in haste with a minimum of preparation.

Lopsided though it is in its coverage, Pelagius' Chronicon is the most important source for many eleventh-century events, such as the division of the realm that took place on Ferdinand I's death (1065). He is also a contemporary and frequent eyewitness for the reigns of Alfonso VI and Urraca; indeed, his is the only contemporary account that covers the entire reign of Alfonso VI, whom he laudingly calls "the father and defender of all the Spanish churches."[23] The reign of Alfonso V before him is covered very briefly, but that of Alfonso's father, Vermudo II, takes up roughly half the entire Chronicon and is highly critical of the king. Pelagius is the only source for the imprisonment of his predecessor, Bishop Gudesteus, by Vermudo in the 990s. The criticism of Vermudo is a useful window onto Pelagius' ideology and bias.[23] Pelagius' Chronicon is mostly interested in ecclesiastical history, especially that of his province, and its description of royal activity is barren, rarely amounting to more than a list of successes, such as cities conquered. The historian credits Divine Providence at every turn, such as when Almanzor was allowed to ravage the Christian states because of Vermudo II's sins. Pelagius was also interested in genealogy, a fact which comes through also in the Liber testamentorum, although his genealogy of the Leonese kings is imperfect.[24] The Chronicon regum Legionensium and the revised chronicle of Sampiro influenced the later authors of the Chronica Adefonsi imperatoris and the Chronica naierensis, and also Lucas de Tuy, Rodrigo Jiménez de Rada, and Alfonso X. Pelagius' importance as a historian is a matter of academic disagreement.[25] He is neither free from legend, nor miracle, nor all invention, but he did not set out to reconstruct the past.

Pelagius also penned an account of the translation of the relics of Pelagius of Córdoba from León to Oviedo and of those of Froilán to Valle César, near Oviedo, which he included in his chronicle.

Liber testamentorum

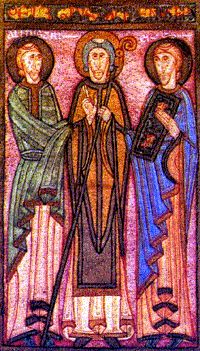

Pelagius also had all judicial documents relating to the diocese collected and copied into a massive cartulary called the Liber testamentorum or Libro (gótico) de los testamentos, compiled around 1120, possibly at the monastery of Santos Facundo y Primitivo in Sahagún.[26] Though it contains falsified, forged, and interpolated documents designed to buttress the claims of Oviedo, otherwise it remains an important compilation for historical research. It is illustrated with colourful miniatures in the Romanesque style, and is the most important monument to this period in the history of painting in Spain.

The Gregorian reform had always desired the reorganisation of the Spanish Church along the same lines as had been during the Visigothic Kingdom. As the see of Oviedo was created during the period of the Asturian Kingdom, Pelagius had recorded the false history of a diocese founded at a place called Lugo de Asturias during the period of the Vandal domination in Spain in the fourth century, before even the Visigoths.[27] Pelagius forged many related documents to demonstrate his diocese's claims against those of Burgos and Lugo. To fend off claims by several sees to be Oviedo's legitimate metropolitan he forged documents claiming that Oviedo had once been a metropolitan seat as well.[28] He made to be forged a letter from Pope John VIII, dated incorrectly to 899, in which Oviedo was made a metropolitan. He had acta (decrees) drawn up for synods which had supposedly taken place at Oviedo in 821 and 872, but for which there is no evidence. In these Lugo and Braga are listed as suffragans of Oviedo and it is claimed that after the Islamic conquest (711) God had translated all the rights and privileges of the church of Toledo to Oviedo, along with her relics, as a punishment for Spain's sins. Pelagius also wrote a history of the movement of the Arca Santa from Jerusalem to Oviedo, which is preserved in the Liber testamentorum and was also interpolated into the Chronica ad Sebastianum in the Liber chronicorum.[27]

Notes

- ^ A catalogue of the Corpus can be found in the Inventario General de Manuscritos de la Biblioteca Nacional, IV (Madrid: 1958), no. 1513, pp. 401–4.

- ^ According to Simon Barton and Richard A. Fletcher (2000), The World of El Cid: Chronicles of the Spanish Reconquest (Manchester: Manchester University Press), p. 65 and n3, this comes from M. G. Martínez (1964), "Regesta de Don Pelayo, obispo de Oviedo," Boletín del Instituto de Estudios Asturianos, 18:211–48.

- ^ According to Barton and Fletcher, p. 70, the sobriquet was coined by Peter A. Linehan (1982), "Religion, Nationalism and National Identity in Medieval Spain and Portugal," Religion and National Identity, ed. S. Mews, Studies in Church History, 18 (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 161–99, at p. 162. Linehan (1993) History and the Historians of Medieval Spain (Oxford), 78, also remarks that Pelagius "was a giant amongst falsifiers in an age which provided him with keen competition and ample opportunity."

- ^ Vicente J. González García, "El obispo don Pelayo, clave para el estudio de la historia de Asturias", El Basilisco, 8 (1979), 72–84.

- ^ Barton and Fletcher, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Bernard F. Reilly (1982), The Kingdom of León-Castilla under Queen Urraca, 1109–1126 (Princeton: Princeton University Press), p. 32 n66.

- ^ Bernard F. Reilly (1988), The Kingdom of León-Castilla under King Alfonso VI, 1065–1109 (Princeton: Princeton University Press), p. 14 and n1.

- ^ a b Barton and Fletcher, p. 69.

- ^ a b Barton and Fletcher, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Reilly (1982), pp. 286–87.

- ^ Reilly (1982), p. 221.

- ^ On the relationship between Pelagius and Urraca, see Barton and Fletcher, p. 67. The grant of 1120 has been partially interpolated, cf. Reilly (1982), p. 79 and n107. The source for his rôle at Sahagún is the Historia Compostelana, I.cxiii (in Enrique Flórez, ed., España Sagrada, XX).

- ^ Barton and Fletcher, p. 66, citing Bernard F. Reilly (1978), "On Getting to be Bishop in León-Castile: the 'Emperor' Alfonso VII and the Post-Gregorian Church," Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History, 1:37–68, esp. pp. 48–51.

- ^ S. Suárez Beltrán (1993), "Los orígenes y la expansión del culto a las reliquias de San Salvador de Oviedo," Las peregrinaciones a Santiago de Compostela y San Salvador de Oviedo en la Edad Media, ed. J. I. Ruíz de la Peña Solar (Oviedo), pp. 37–55, esp. pp. 46–51, has yet to be consulted.

- ^ Julie A. Harris (1995), "Redating the Arca Santa of Oviedo," The Art Bulletin, 77(1):82–93.

- ^ Barton and Fletcher, p. 66 and n10. Pelagius is named as Bishop of Oviedo in documents of March and April 1142 and March 1143.

- ^ Edited in Manuel Risco (1793), España Sagrada, 38:372–76.

- ^ Harris, 90.

- ^ The definitive modern edition is Benito Sánchez Alonso (1924), Crónica del Obispo Don Pelayo (Madrid). A partial Spanish translation is available by J. E. Casariego (1985), Crónicas de los reinos de Asturias y de León (León), pp. 172–81. An English translation can be found in Barton and Fletcher, pp. 74–89.

- ^ For the relationship between Pelagius and Sampiro, see Justo Pérez de Urbel (1951), "Pelayo de Oviedo y Sampiro de Astorga", Hispania, 11(44):387–412.

- ^ Rodrigo did not become Count until 1121 and the first reference to his marriage dates to July 1122. Additionally, Pelagius refers to the marriage of Elvira, daughter of Alfonso VI, to Roger II of Sicily in 1118 (cf. Reilly, p. 14).

- ^ a b Barton and Fletcher, 71.

- ^ a b Barton and Fletcher, pp. 72–73.

- ^ M. Calleja Puerta (1999), "Una genealogía leonesa del siglo XII: la descendencia de Vermudo II en la obra cronística de Pelayo de Oviedo", La nobleza peninsular en la Edad Media (León), pp. 527–39, is yet to be consulted.

- ^ According to Barton and Fletcher, pp. 72–73, nn. 33 and 36–37, F. J. Fernández Conde (1971), "La obra del obispo ovetense D. Pelayo en la historiografía española," Boletín del Instituto de Estudios Asturianos, 25:249–91, esp. pp. 250–55, is highly critical of Pelagius' historiography, and B. Sánchez Alonso (1947), Historia de la historiografía española (Madrid), p. 117, lambastes it as superficial, while A. Blázquez y Delgado Aguilera (1910), "Elogio de Don Pelayo, obispo de Oviedo and historiador de España," Memorias de la Real Academia de la Historia, 12:439–92.

- ^ The modern edition is F. J. Fernández Conde (1971), El Libro de los Testamentos de la catedral de Oviedo (Rome).

- ^ a b Barton and Fletcher, p. 70.

- ^ Demetrio Mansilla (1955), "La supuesta metrópoli de Oviedo," Historia Sacra, 8(16):259–74, esp. §. II, pp. 264–74, on the "Teoría del obispo Don Pelayo sobre la metrópoli de Oviedo: fundamentos y crítica de la misma".