Indian Larry

Indian Larry | |

|---|---|

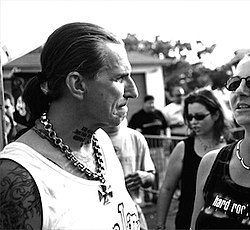

Indian Larry at bike rally in Daytona Beach, Florida, 2003 | |

| Born | Lawrence DeSmedt April 28, 1949 |

| Died | August 30, 2004 (aged 55) |

| Occupation(s) | Motorcycle builder and artist, stunt rider, biker |

| Notable work | Grease Monkey, Daddy-O (Rat Fink), Mr. Tiki, Wild Child, Chain of Mystery |

| Style | Old school (1950's–1960's hot rod - motorcycle culture) Kustom Kulture |

| Spouse | Andrea "Bambi" Cambridge |

Indian Larry (born Lawrence DeSmedt; April 28, 1949 – August 30, 2004) was an American motorcycle builder and artist, stunt rider, and biker. He first became known as Indian Larry in the 1980s when he was riding the streets of New York City on a chopped Indian motorcycle. Respected as an old school chopper builder, Larry sought greater acceptance of choppers being looked upon as an art form. He became interested in hot rods and motorcycles at an early age and was a fan of Von Dutch and Ed "Big Daddy" Roth, whom he would later meet in California.

Wide acknowledgment of Indian Larry's talent only came in the last few years of his life. He died in 2004 from injuries sustained in a motorcycle accident while performing at a bike show. His bike, Grease Monkey, was featured in Easyriders magazine in September 1998. In 2001 Indian Larry participated in the Discovery Channel program Motorcycle Mania II, followed by three different Biker Build-Off programs. During this period he and his team built the motorcycles, Daddy-O (known to most people as the Rat Fink bike), Wild Child, and Chain of Mystery.

Early life and education

Indian Larry was born Lawrence DeSmedt in Cornwall-on-Hudson, New York on April 28, 1949. He grew up in the Newburgh, New York area including the town of New Windsor.[1][2] The oldest of three children, with two younger sisters, Diane and Tina, Larry was described by his mother, Dorothy, as "a good boy, but mischievous."[3] Larry's strict father, Augustine, was a carpenter at United States Military Academy and had built the family's home. He wanted his son to follow in his footsteps in the carpentry trade.[3] As a boy Larry liked Lincoln logs and Ed "Big Daddy" Roth Revell plastic model kits.[4] Roth, a legendary California artist and hot rod builder, was a big influence on Larry and his style would later bubble up to influence Indian Larry's motorcycle designs.[5]

Larry attended a Catholic elementary school where he suffered abuse. The nuns would hit his knuckles until they bled and lock him in dark closets.[6][7] He kept what was occurring to himself, and didn't tell his family what was going on. When his mother asked about his knuckles, Larry would always just say that he had gotten into a fight.[3] It wasn't until years later that his family learned what had actually happened.[7] As a child Larry was described as being sensitive and artistic, and "feeling more than most."[8]

A well-known anecdote about Indian Larry is that as a kid he attempted to build a bomb in his parents' basement in order to blow up the Catholic school.[3][6] The contraption exploded taking off the little finger of Larry's left hand. Another version of the story states that the injury occurred while he was trying to build a skyrocket for the 4th of July.[9][10] When asked about the experience of being maimed as a kid during a 2003 Biker Build-Off program, Larry seemed to have come to peace with it:

Like most horrible atrocities that happen to you in life, when you look at them in retrospect, it's usually a blessing or a lesson. It's not much fun when you're caught up in it. But it's better. You can get into tighter spots. Makes you a better mechanic.[11]

As a youth Larry participated in the Boy Scouts. His scoutmaster, Gerald Doering, had raced Indian motorcycles which had an influence on Larry.[12]

Larry's first build was when he took his little sister Tina's tricycle and equipped it with Schwinn bicycle handlebars and a lawn mower engine.[3][6][13] According to a Rolling Stone interview that was mentioned in a New York Times article, Larry's first motorcycle was a 1939 Harley Knucklehead that he bought when he was a teenager for a couple hundred dollars. "Within hours, he had taken it apart, and it took him nine months to put it back together."[14]

As a young man Larry learned how to weld from Conrad Stenglein in the Newburgh, New York area. The shop was simple. As Stenglein described it: "All we had in the shop was a welding machine, torches, grinder, body putty, stuff like that."[15] Quality of work was important to Larry early on. Stenglein said that "Whatever part we made for a bike, it had to be strong and had to be good, that was our thing. It had to be perfect. If Larry put something on a bike that he didn't like, he'd cut it off. That's how he was."[15]

A month before he was to graduate from high school, Larry told his mother that he was heading to California to join his younger sister Diane who was deeply immersed in the 1960s counterculture (Diane had run away from home when she was 16).[16] In California Larry also took part in the scene and delved into drugs. Larry saw his sister Diane as a kindred spirit who understood what it was like to feel like an outsider in society.[17] On June 21, 1971, Diane was murdered. Larry accompanied her body back to their hometown for her funeral. The experience was emotionally devastating to him.[3][18]

Coupled with his grief, Larry was spiraling into drug addiction. To pay for the drugs he was robbing stores. The cops had an idea that it was Larry but had not been able to catch him so they set up a sting operation. In 1972 as Larry was exiting a bank he had just robbed, he was fired upon by two police officers. He narrowly escaped being killed when one of the bullets grazed his eyebrow.[3][19] At the age of 23, Larry was sent to Sing Sing prison for three years. During his incarceration Larry earned his GED, and started taking courses in welding and mechanics. Prison was "the place where he honed all his best mechanic skills."[20] He also asked his mother to send him a dictionary and books on philosophy and other topics. He was released in September 1976.[21]

Move to New York City

After completing parole, Larry relocated to New York City where he became involved with the underground scene. The first magazine article about Indian Larry was in Iron Horse Magazine in 1987.[22] It featured his 1950 Indian Chief chopper with red-orange flames.[23] It was during this period that people began to call him Indian Larry.[24] In the 1980s he hung out with Robert Mapplethorpe and Andy Warhol.[24] Mapplethorpe in particular was "attracted to Indian Larry's 'crash and burn'" lifestyle.[14] One of the photographs that he took of Indian Larry ended up on the cover of Artforum magazine.[6]

Indian Larry began working in different motorcycle shops in New York City and New Jersey during the 1980s and early 1990s. Often he would be rebuilding motors out of his apartment.[25] For many years Larry struggled with alcohol abuse and heroin.[26] In November 1991, during a period when he was living around the Bowery, Larry was going through severe withdrawals one night, wandering the streets cutting himself with a broken beer bottle. Larry would later say, "I was homeless, shirtless, penniless, showerless...I had nothing. I had nothing left".[3][27] According to Larry's sister Tina, when a cop arrived on the scene shining a spotlight in Larry's face, Larry told him, "Just shoot me." They committed him to Bellevue Hospital.[6][28] It was through Bellevue that Larry got connected up with a drug and alcohol program.[29]

Larry had "1991" and "1994" tattooed on his arm, as he explained that he had to go back after his initial treatment.[3] Larry struggled with a familiar cycle for years. As friend and bike building partner Paul Cox explained: "...he would go through periods of time when he didn't think he deserved fame or whatever, and would sabotage himself by doing drugs. Larry would attack himself internally and head down a self-destructive spiral."[30] It was not until the late 1990s that Larry was finally able to free himself and stop using.[31] Mentioning the long journey that it took, Larry expressed that he didn't think that he could do it all over again. "It was too hard," he said.[3] Larry's friend photographer Timothy White expressed, "drugs didn't belong with Larry and I think Larry knew that and it wasn't until he got to a point that he really realized that – only at that point could he let it all go. And once he did, his life changed completely. It changed completely, like nobody I've ever seen."[3]

Chopper builder

Indian Larry, along with Paul Cox, Fritz "Spritz by Fritz" Schenck, Steg Von Heintz, and Frank, formed the crew at Psycho Cycles on New York's Lower East Side beginning in the early 1990s.[9] During this period they created a distinct New York City chopper style.[32] In 2000, Larry and friends opened Gasoline Alley in Brooklyn.[32]

Larry is credited with helping to re-popularize the stripped down, tall handlebar, foot clutched, jockey shifted, no front brake or fender, small gas tank, open piped, kick start only, stock rake choppers that prevailed in the 1960s, before long front ends became popular (Larry explained during his first Biker Build-Off, that he preferred nimbleness in a bike so he could ride at high speeds along the mountain switchbacks).[33]

When building a chopper, Larry could draw upon what he had mastered over the years in the fields of mechanics, welding, and metal fabrication. Among custom bike builders, Indian Larry was known and respected for having mastered the old-school style of building and remaining loyal to it.[34] Larry considered himself to be a "gearhead" originally, and was rooted in the hot rod culture of the 1950s and 1960s. During the Biker Build-Off period in 2003–2004, Larry's appreciation for modern horsepower and twin carburetors for increased fuel/air intake was expressed in his builds.[33]

Larry explained, "I'm a chopper builder. Old-time, old-school chopper builder. But I like the modern technology that's involved. So the bikes run better, perform better. And we have more fun with them."[33]

In the art of building a bike, Larry preferred old school methods and didn't use CNC machines.[35] He favored Paughco rigid frames and panhead motors.[24] Larry liked being able to see all of the nuts and bolts and mechanics of a bike, rather than concealing those elements in a bike's construction.[3][24] The way that Larry approached building a bike was evident early on. The man who taught Larry the craft of using a welding torch said that he remembered Larry not wanting to grind down welds if they were good because Larry "felt it showed your craftmanship."[15]

Larry's childhood friend, Ted Doering, who knew Larry when he was first learning to build and would chrome parts for him, said that Larry had even envisioned the idea for a "'clear,' see-through transmission case" in order to "view the gears working". Doering added that Larry "would fabricate or customize every piece because on a motorcycle, you can see everything."

Larry's shop partner, Paul Cox, (who first met Larry at Sixth Street Specials in the East Village, and started working with him at Psycho Cycles around 1992)[32] explained how Larry conceived the idea for a new chopper build: "Working alongside him you realized how much he ran on instinct. Built-in instinct. He would rarely make a sketch or jot down notes...he just envisioned what he wanted in one wide-eyed flash and would turn to you with a look like he saw God. At that point it was 'all over but the cryin,' he would say."[36]

Indian Larry appeared in Easyriders magazine in 1998 in an article entitled, "Hardcore NYC Troubadors".[37][38] Later that same year the magazine profiled Larry with his motorcycle, Grease Monkey,[39] which won the 1998 Editor's Choice Award at the Easyriders Invitational Bike Show in Columbus, Ohio, which was an important recognition by the biker world of Larry's talent.[40]

The beginning of Indian Larry becoming known to the general public was his appearance in the Discovery Channel program, Motorcycle Mania II in 2001. The program's primary focus was on customizer Jesse James, but it also featured different scenes profiling Indian Larry as he and the group (which included Jesse James, Chopper Dave, and Giuseppe Ronsin) set out to ride 1400 miles from Long Beach, California to the Sturgis 2001 Black Hills Classic in Sturgis, South Dakota. When one of the choppers breaks down in Southern Utah, Larry is shown performing his mechanical skills on the bike in a supermarket parking lot (when his own bike has magneto problems, Larry explains to the camera, "If the bike is not running; if it's leaking oil; and if it's dirty. That's about the only three things that will really get to me.")[41] The program also shows Larry displaying his famous neck tattoo, sharing snippets of his personal philosophy, and doing riding stunts – this included him reclining back on his bike, Grease Monkey,[42] with his legs outstretched over the handlebars, and standing up on the saddle with his arms outstretched to the side as he speeds down the highway. The group also visits Denver's Choppers in Las Vegas, Nevada (now in Reno) where Larry is shown meeting chopper builder, Mondo Porras for the first time.

Biker Build-Off

Larry wanted to "elevate the art of the motorcycle" in the general perception and the art world.[3] He stated, "As far as I'm concerned, it is one of the highest art forms, because it combines all media: sculpture, painting, as well as the mechanics, and it's just a lot more than any one single medium"[33][43] (In addition to metalwork and painting, Larry included engraving and leather work to the list in another interview).[44] He explained that being a chopper builder requires being able to create from the abstract, and having a sense for aesthetics, while also possessing mechanical skills to deal with "extremely critical tolerances...like 2/10,000 of an inch in the motors".[44][45]

The Biker Build-Off programs provided a public forum to do this. Indian Larry participated in three different Biker Build-Off programs on the Discovery channel:

| Competitors | air-date (premiere) | Chopper built | Ride |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indian Larry vs. Paul Yaffe | September 1, 2003 | Daddy-O (Rat Fink) | Rode north through 4 states: Beginning in New York City – Connecticut – Massachusetts – to the Laconia rally in New Hampshire. |

| Billy Lane vs. Indian Larry | September 1, 2004 | Wild Child | Rode northwest through 4 states: Beginning in St Louis, Missouri – Iowa – Nebraska – to the Sturgis rally in South Dakota. |

| Indian Larry vs. Mondo | February 8, 2005 | Chain of Mystery | Rode south through 4 states: Beginning in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania – West Virginia – Virginia – to the rally in Concord, North Carolina. |

The premise of each 45 minutes program was to profile two different custom motorcycle builders, each from a different part of the United States, and film them and their crews at work in their respective shops building a unique bike from start to finish within a set number of days. (They were given 30 days to build for Larry's first two Biker Build-Offs, and 10 days for his third and final build for the program).[44] The format seemed perfectly suited to Larry, as television viewers witnessed segments showing the culmination of years of bike building experience interspersed with Larry's philosophical insights. Also shown helping Larry in the construction of each bike were Paul Cox and Keino Sasaki (pronounced "cane-o") from his shop.[46]

The bike builders would then meet at a neutral location and be filmed riding across several states to a particular bike show. The road trip was meant as a testing ground. Upon arrival at the bike shows, the general public in attendance could view the bikes and vote their preference between the two. Usually on the final day of a bike show, the votes would be tallied, a winner announced, and a trophy awarded. Indian Larry was voted the winner in all three Biker Build-Off competitions that he competed in. His second trophy was cut up and shared with his opponent, Billy Lane and the audience, after Larry unexpectedly declared an exact draw after it was announced that he had won in the voting.[45]

Indian Larry's fatal motorcycle accident occurred during the filming of his third Biker Build-Off in 2004, on the same day, and at the same bike show, where the votes were being tallied to determine the winner.[44]

Last build: Chain of Mystery

Indian Larry and crew built the Chain of Mystery bike for the final challenge. Larry said that the original idea for the bike's frame came to him in a flash of inspiration. He explained that his most creative ideas for a new build would flash across his mind in the form of an image, and then it would be his job to relentlessly chase that vision during a build until the image materialized in the finished product.[3] Chain of Mystery utilized a frame concept that had never been done before.[44] Using a jig as a guide, the heavy links of a chain, normally used for towing heavy vehicles, were welded together until the frame took shape (the shop's Eddie Mcgarry was the project welder). Since the frame is essentially the spine of the bike, any weaknesses in the welds could prove fatal, especially considering that Larry really pushed his bikes to perform when riding them.[44][47] As it turned out, the bike held up, and Larry rode the chopper to what would be his final bike show.

Personal life

The right bike, the right day, the right road, I just pretty much feel

at one with the universe. When I feel like I don't fit anywhere or I'm

lonely or I'm like all screwed up in the head, I get on my bike and go

for a ride and it's like all of the sudden, I'm fixed.

— Indian Larry during a Biker Build-Off program[44]

Indian Larry considered himself a "lone wolf", and was not a member of a motorcycle club, nor of what are termed outlaw motorcycle clubs.[14][33] Larry loved being on the road on his bike and living the biker lifestyle.[48]

When Indian Larry first met the woman that would become his wife, Andrea "Bambi" Cambridge, in 1996, her first impression of him is that she thought he looked like "a total mass-murderer".[6] People would go out of their way to avoid him on the subway, but the moment Larry would start talking he'd instantly put them at ease with his sense of humor.[49]

Bambi relates in the biography, Indian Larry: Chopper Shaman, stories about how she first knew about Larry and the experiences that occurred before they came to be in a relationship. Before they officially started to date in 1997, they hung out together at a bar and Larry kept putting quarters in the jukebox, playing romantic songs by Roy Orbison and Patsy Cline. This was when he was still drinking, and Bambi wrote that at one point he started crying, and said to her, "No one else is ever really going to know my soul". And Bambi thought to herself, "I will. I could do that."[50]

Larry proposed to Bambi in the Bahamas. He surprised her by getting her name tattooed in circus letters on his chest. When he showed it to her he said, "You know, you only have one girl's name tattooed over your heart in a lifetime."[51] They had a circus themed wedding at Coney Island (Coney Island was where they were both involved with the sideshow. She performed as "Bambi the Mermaid", and Larry's act involved lying on a bed of nails while large blocks of ice would be broken over his chest by a girl with a sledgehammer; or she would stand on his stomach.[52] The experience performing in front of audiences helped prepare Larry for his later appearances on camera and performing at bike shows). Larry's marriage to Bambi gave him a lot of strength, and gave him something to believe in.[3]

Philosophy

Timothy White explained, "Larry lived his art. There's no doubt about it. His life was his art".[3] Having experienced and overcome many extreme tests in life, Indian Larry adopted the question mark as his life logo. Larry "had a lot going on in his head",[53] and was by nature analytical, and a deep thinker. But ultimately he thought that one should just "roll with the mystery", and "live in the moment".[54] Larry often expressed to those around him that he didn't pretend to know what was going on.[45][55] Basically applying the adage that wisdom is understanding what one doesn't know. Larry explained:

I don't know anything in life. I just show up and go with the flow. I'm not a religious person but I'm a very spiritual person. Spirituality is instinctive and I believe it's more of a Zen type of thing. You stay in the moment and you'll get the right answers, the correct answers. Every motorcycle is always a spiritual experience. Choppers specifically are a very integral part to my spirituality. When I go out for a ride or something I'm exactly in the moment. It's like meditation. I'm in the flow.[33]

One of Larry's attributes that was well known to the public was his many tattoos, although he didn't have most of his tattoos until later in life (he got his neck tattoo when he was in his mid 40s in the mid-1990s).[34] The tattoo on his neck, which went across the front of his throat, was often commented on. The tattoo read:

IN GOD WE TRUST

VENGEANCE IS MINE

NO FEAR

SAYETH THE LORD

The lettering of the middle two lines was in reverse so that it could be read in the mirror.[6] Larry said that it was his way to remind himself not to judge others and that revenge was not his job.[56] When asked about its meaning during the Motorcycle Mania II program in 2001, Larry explained with a big grin on his face, "...it's my philosophy. Go through life see what's up. Try not to kill nobody!"[41] Larry often expressed his belief that life is "a really precious, short gift."[57]

Film and television

Indian Larry was involved with acting, and performed stunt work for films. He appears in the documentary, Rocket's Red Glare!, and performed stunts for the films, Quiz Show, Muscle Machine, My Mother's Dream, and 200 Cigarettes. He appeared on the Late Show with David Letterman, among other appearances in film and television.

Death

In 2004, Indian Larry was living in the East Village with Bambi, working at his shop in Williamsburg, Brooklyn and was appearing at bike shows and rallies around the United States.[46] He was regularly being recognized and approached by fans. When interviewed for the Discovery Channel in July 2004, Larry said, "I just feel like that I'm maybe slightly starting to fit in somewhere and slightly starting to be accepted."[3] His friend Timothy White said: "It was finally making sense to him – all his turmoil, all his craziness...everything was just all coming together into this one moment of recognition that he was coming to..."[3]

In August 2004, Indian Larry and crew participated in the third Biker Build Off competition building the chain frame bike, Chain of Mystery. This time competing against Mondo Porras, whom he first met while filming Motorcycle Mania II in 2001 (Mondo, who began building choppers in 1967 with the late Denver Mullins in California, is known for his long down tube, stretch frame choppers. He and Larry had hung out together in Hawaii while appearing at a bike show there two months earlier).[58]

Both bike builders met in Pittsburgh, and then spent three days riding through Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Virginia, and North Carolina to arrive at the Liquid Steel Classic and Custom Bike Series bike show in Concord, North Carolina, north of Charlotte. Larry was scheduled to perform stunts at the event the afternoon of August 28, 2004, such as riding through a tunnel-of-flames.

Larry was always careful to build his bikes with aligned geometry so that they did not veer to the side while riding down the road. One of the benefits derived from this level of bike stability is that it allowed Larry to perform his stunts on his own bikes, such as standing fully upright on the seat while speeding down the road.[44][45] This is a stunt Larry had done countless times over the years. After standing up while balancing himself, Larry would then outstretch his arms in a "T" configuration, called a "crucifix" pose. Larry rode through the tunnel-of-flames that afternoon in front of a crowd of several thousand people. A short time later, Larry attempted to perform the standing stunt again, this time on his bike, Grease Monkey.[35][42]

Larry had expressed apprehension that day about performing the stunt. Larry shared with Mondo that he did not have a good feeling about doing it, but he felt pressure to do it.[35] Bambi said that normally Larry did this stunt after the bigger stunts as "his way of blowing off steam...winding down."[14] As Larry was performing the maneuver, something went wrong and the front end of his bike started to wobble.[59] Rather than being able to jump down in the seat and regain control, Larry fell off the bike, hitting his head.[35] Larry sustained serious head injuries and he was airlifted to the Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte. Indian Larry died from his injuries on Monday, August 30, 2004, at 3:30am.[3] He was 55 years old. The last words that Larry uttered were to his wife Bambi (who was at the event) saying, "Sweetie, sweetie."[6]

Legacy

Fellow bike builder, Mondo said after Larry's death, "I think he humbled a lot of people because he was so real and genuine."[35]

A tribute bike was built by Billy Lane, Keino Sasaki, Paul Cox, and Kendall Johnson in the Indian Larry shop which was filmed by Discovery Channel for a one-hour biography special on the life of Indian Larry. The name, Love Zombie, was chosen since this was a name that Larry had previously thought up for a future chopper he had wanted to build. Billy Lane hand-fabricated the gas tank, among the other contributions made by the team to build the bike[3][60] (a vintage Pontiac car hood ornament of an Indian chief's bust was incorporated into the design of the gas tank). Robert Pradke of Eastford, Connecticut applied purple paint with green flames.

Two books were published about Indian Larry in 2006:

- Indian Larry: Chopper Shaman by Dave Nichols with Andrea "Bambi" Cambridge; photographs by Michael Lichter

- Indian Larry by photographer Timothy White

| Notable Chopper Builds | Details | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Grease Monkey[40][42][61] | Larry's personal ride. First Indian Larry Bike featured on cover of Easyriders magazine (No. 303 September 1998). Panhead transplanted from his previous bike, Voodoo Chili, into Grease Monkey in 1996/97. Modified Paughco frame. Four-speed transmission. Ceriani front end. Frame and jockey shifter are nickel-plated. Black leather seat by Paul Cox. Rear display, orange oil filter (as with all of Larry's bikes, the oil filter was mounted behind the transmission to hang near the rear tire). Bike that Larry is shown riding on Motorcycle Mania II program. | Red metal flake paint and pearl white flames on gas tank.[62] "Indian Larry" name logo and two biker crosses in gold leaf on top of tank. Naked rear fender. "Grease Monkey" airbrushed on chain belt. Larry chose mediums that were popular in the 1960s: metal flake paint and gold leafing. |

| Daddy-O (Rat Fink)[33][63][64][65] | Built during Indian Larry's first appearance on Biker Build-Off (vs. Paul Yaffe) which culminated at the Laconia rally. Bike appeared in the December 2004 issue of Easyriders. Inspired by hot rods with dual carbs to increase fuel/air intake. 88" motor. Baker 6-speed transmission. Mustang gas tank. Indian Larry twisted Springer front-end. Hand-spoked wheels. Chrome oil filter. Paul Cox hand-tooled, red buffalo hide seat. Large question mark symbol on sissy bar. Shifter knob is white ball with red spirals. Bike a tribute to Ed "Big Daddy" Roth who Larry said was his inspiration to get into the business. | Robert Pradke paint and airbrushing. Larry stated that it looks "late 1960s".[33] Gold metal flake paint. Red flames with pink borders. Green Rat Fink character airbrushed on top of gas tank against ruby red background. Among the lettering, "In memory of Ed "Big Daddy" Roth 1932-2001". Green pin striping on rear fender with Indian Larry name logo in gold leaf, and "Gasoline Alley" and "New York City" in silver leaf against ruby red background. Chain belt airbrushed: "Way Out Daddy O from Weirdsville".[66] |

| Mr. Tiki's Shop Droppings (Mr. Tiki)[67][68] | Tribute to 1960s Tiki culture for Bambi the Mermaid; Constructed for Easyriders Centerfold Tour 2004. Underlying frame consists of steel rings welded to the frame. Name comes from incorporating different parts lying around the shop to keep costs low - "backyard building".[67] Panhead motor. Dark brown tiki shifter knob. Paul Cox leather seat made to resemble Polynesian weave. | Robert Pradke's molding and paint creates illusion that bike frame is made of yellow bamboo.[69] Paint stylized as wood grain on gas tank and fender. "Indian Larry" name logo in gold on side of dished tank and red and yellow question marks. Tiki airbrushed on top of tank. Green and purple pin striping on rear fender with lettering, "Easyriders Centerfold Tour 2004". |

| Wild Child[45][70][71] | Second Build-Off appearance (vs. Billy Lane at Sturgis). Larry said during the taping of the program that up to that point it was the "best bike" he had "ever-ridden," and "ever-built" in "his whole life".[45] Chromed twisted down tube. Shovelhead front cylinder, Panhead rear. Twin carburetors. Baker six-speed transmission. Paul Cox created the concave sides of the gas tank by welding round stock and then hammer dishing it. Inverted Ceriani front end. Billet wheels. Jockey shift knob is white ball with blue spirals. As Larry explained it, "You're riding out of the 60s, but on 2003 equipment."[45] Was featured on cover of Easyriders magazine (No. 322, p. 18-22). | Robert Pradke paint (Custom Auto Design). Root beer metal flake paint. White flames bordered with green pinstripe. Metal leaf design over sterling silver leaf on side of dished tank with "Indian Larry" name logo in gold leaf and "Gasoline Alley, New York City" in black lettering. Open belt drive airbrushed: "Wild Child". |

| Chain of Mystery[44][72][73] | Built during Larry's third and final Biker Build-Off (vs. Mondo from Denver's Choppers). Was originally started as Larry's personal bike. Original, innovative frame made from welded tow chain links. Combination Panhead front cylinder - Shovelhead rear cylinder. S&S L Carburetor in front and S&S B Carburetor in rear. Brake rotor laser cut with question marks (also referred to as question crosses). C J Allan engraved parts, including panhead rocker box cover with Indian Larry question marks. Jockey shift knob is a white ball with red spiral. Paul Cox hand-tooled, American cowhide leather seat of cartoon of Indian Larry as the Grease Monkey. | Frame, gas tank, and fender were powder coated "starburst violet" color, which Larry described as being "definitely Munster Koach".[44] Robert Pradke painted graphics and applied clear coat. "Indian Larry" name logo in gold leaf and leafing of Psychedelic floating question marks on gas tank which are outlined in red and purple. Leafed flames outlined in green. Von Dutch style pin striping in red/orange and purple. Lettering on top of tank near seat says, "God Help Me!!" Pradke originally airbrushed the chain belt: "Chain of Mystery". Larry commented: "You don't see bikes like this that often. That's what I shoot for something that's just mind-bending".[44] |

References

- ^ Kessler, Donna; DeSmedt-Wells, Tina (2012-09-10). "Indian Larry to be remembered at Motorcyclepedia Saturday". Times Herald-Record. Retrieved 2012-11-11.

- ^ "Indian Larry exhibit". Archived from the original on 2013-01-06. Retrieved 2012-11-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Biography special on Indian Larry. Program included interviews with Larry's sister Tina, his mother Dorothy, wife Bambi, friend Timothy White, and others; footage of Larry from past Biker Build-Off programs; segments showing Billy Lane, Paul Cox, Keino, and Kendall Johnson and crew building tribute bike they named "Love Zombie". Executive Producer: Thom Beers. Co-Executive Producers: Tracy Green, Hugh King. Producer/Writer/Editor: Larry Law. Discovery Channel. 2005.

- ^ Nichols, Dave; Cambridge, Andrea "Bambi"; Lichter, Michael (2006). Indian Larry: Chopper Shaman. Motorbooks. p. 19.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 134.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lieb, Rebecca (February 2006). "Remembering Indian Larry: Joe Coleman's Homage to the Ultimate Motorcycle Artist". Juxtapoz: Arts & Culture Magazine. No. 61. pp. 40–47.

- ^ a b Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 20, 22, 29.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 38.

- ^ a b Babolcsky, "TBear" Ted (2007-01-25). "Indian Larry Tribute: The Emperor of Old Skool". bikernet.com. Retrieved 2012-02-05.

- ^ Both versions are hinted at in the 2006 Tom Zimberoff book: Art of the Chopper II. ISBN 978-0-8212-5815-6.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. p.24.

- ^ Doering and his son Ted, who was in the scout troop with Larry, would later open a motorcycle museum in New York, the Motorcyclepedia. Ted had opened a chopper shop in 1969 out of a shed on the family's property, and the Doerings started selling wholesale parts in the early 70s focusing mainly on older Harley-Davidson models and had collected Indian motorcycles over the decades. See [1] and [2] Archived 2012-10-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 20.

- ^ a b c d Saxon, Wolfgang (2004-09-01). "Indian Larry, Motorcycle Builder and Stunt Rider, Dies at 55". New York Times. Retrieved 2012-01-13.

- ^ a b c Kessler, Donna (2012-11-05). "Indian Larry Day pays tribute to the builder and the man". Times Herald-Record. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 30.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 40.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 30, 35, 38, 40.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 42, 43.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 48, 52.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 56.

- ^ Issue # 70 November 1987

- ^ "Iron Horse article on Jockeyjournal.com". Retrieved 2012-02-11.

- ^ a b c d Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 60.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 67.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 104, 107.

- ^ Describing one incident to his friend, artist Joe Coleman, Larry said, "Going through withdrawal, my whole body shook like an engine going through a full stop." (See: Lieb, Rebecca. "Remembering Indian Larry: Joe Coleman's Homage to the Ultimate Motorcycle Artist". Juxtapoz: Arts & Culture Magazine February 2006 Issue #61. pp. 40–47.)

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 105, 106.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 107.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 65.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 65, 67.

- ^ a b c "Paul Cox Industries: About".

- ^ a b c d e f g h Executive Producer: Thom Beers; Co-Executive Producer: Hugh King. (September 1, 2003). "Indian Larry vs Paul Yaffe". Biker Build-Off. Discovery Channel.

- ^ a b Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 131-132.

- ^ a b c d e Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 160.

- ^ White, Timothy (2006). Indian Larry. New York City, NY: Merrell. p. Introduction. ISBN 978-1-8589-4411-1.

- ^ February 1998, No. 296, p. 87-91

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 68. 123.

- ^ September 1998, No. 303

- ^ a b Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 70-71.

- ^ a b Executive Producer: Thom Beers. "Motorcycle Mania II". (Motorcycle Mania series). Discovery Channel – 2001.

- ^ a b c "Photograph of Grease Monkey (Timothy White)". Morrison Hotel Gallery. Archived from the original on 2015-10-25. Retrieved 2012-05-30.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 145.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Executive Producer: Thom Beers; Co-Executive Producer: Hugh King; Producer/Writer: Craig Constantine. Editor: Tim Roche (February 8, 2005). "Indian Larry vs Mondo". Biker Build-Off. Discovery Channel.

- ^ a b c d e f g Executive Producer: Thom Beers; Series Producer: Hugh King; Producer/Writer: Caty Burgess; Editor: Philippe Ramsay LeMieux (September 1, 2003). "Billy Lane vs Indian Larry". Biker Build-Off. Discovery Channel.

- ^ a b Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 141, 142, 147.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 87.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 132, 148, 159.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 62.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 112.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 120.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 100-101, 120.

- ^ As explained by Timothy White in the Discovery Channel bio of Indian Larry

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 148.

- ^ Pavony, Eric Harris (2004-10-03). "Indian Larry 1949-2004". Block magazine. Archived from the original on 2013-01-18. Retrieved 2012-01-13.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 124.

- ^ An anecdote illustrating Larry's philosophy

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 159

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 159, 160.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 170-173.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 158.

- ^ Indian Larry: Chopper Shaman (p. 71): Larry did the molding, with the paintwork by Cassato Airbrush.

- ^ "Photographs of Daddy-O (Michael Lichter)". lichterphoto.com. Archived from the original on 2012-02-02. Retrieved 2012-02-02.

- ^ Courter, Josh (2011-12-11). "Indian Larry's Daddy-O". Kustoms and Choppers magazine. Archived from the original on 2012-01-09. Retrieved 2012-01-13.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 72-75.

- ^ "Timothy White photograph: overhead shot showing detail of Daddy-O". Morrison Hotel Gallery. Archived from the original on 2015-10-26. Retrieved 2012-06-02.

- ^ a b Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 78-81.

- ^ "Photographs of Mr. Tiki (Michael Lichter)". lichterphoto.com. Archived from the original on 2012-02-02. Retrieved 2012-02-02.

- ^ "Timothy White photograph: example of Robert Pradke's molding and paint to resemble bamboo on Mr Tiki". Morrison Hotel Gallery. Archived from the original on 2015-10-26. Retrieved 2012-06-02.

- ^ "Photographs of Wild Child (Michael Lichter)". lichterphoto.com. Archived from the original on 2012-08-26. Retrieved 2012-02-02.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 82-85.

- ^ "Photographs of Chain of Mystery (Michael Lichter)". lichterphoto.com. Archived from the original on 2009-06-05. Retrieved 2012-02-02.

- ^ Nichols; Cambridge. - p. 86-89.