Orchid Island

Native name: Pongso no Tao | |

|---|---|

| |

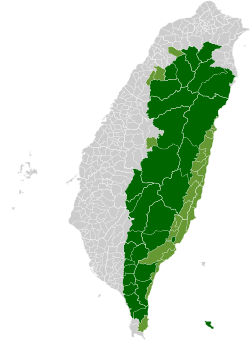

Orchid Island in Taiwan | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Philippine Sea |

| Coordinates | 22°03′N 121°32′E / 22.050°N 121.533°E |

| Area | 45 km2 (17 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 552 m (1811 ft) |

| Highest point | Mount Hongtou |

| Administration | |

Republic of China | |

| Township | Lanyu |

| County | Taitung |

| Province | Taiwan (streamlined, government dissolved) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 5,255 (February 2023) |

| Ethnic groups | Tao, Han |

| Orchid Island | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The shore of Orchid Island from an imperial Japanese publication (c. 1931) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 蘭嶼 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Orchid Islet(s) | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Former names | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 紅頭嶼 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 紅頭嶼 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | こうとうしょ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Katakana | コウトウショ | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Lesser Orchid Island | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Lesser Orchid Island | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 小蘭嶼 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Little Orchid Islet | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Orchid Island,[2] also known by other names, is a 45 km2 (17 sq mi) volcanic island off the southeastern coast of Taiwan, which Orchid Island is part of. It is separated from the Batanes of the Philippines by the Bashi Channel of the Luzon Strait. The island and the nearby Lesser Orchid Island are governed as Lanyu Township in Taitung County, which is one of the county's two insular townships (the other being Lyudao Township).

Names

Orchid Island is known by the Tao people indigenous to the island as Pongso no Tao ("island of human beings"). It was also known by the Tao as Ma'ataw ("floating in the sea") or Irala ("facing the mountain"); the latter being contrasted with the Tao name for the Taiwanese mainland – "Ilaod" ("toward the sea").[3]

In the 17th century, it appeared on Japanese maps as "Tabako",[4] a name borrowed into French[4] and English as "Tabaco". It is still known by Filipinos as Botel Tobago, a name also formerly used in English.[5] Lesser Orchid Island was similarly known as "Little Botel-Tobago".[5]

"Orchid Island" is a calque of the Chinese name, written 蘭嶼 in traditional characters, although strictly the second character means an islet rather than an island. The name honors the local Phalaenopsis orchids and was established by the Republic of China government in 1947.[6] It is also sometimes known as Lanyu or Lan Yu, derived from Pinyin romanization of the name's Mandarin reading (Mandarin Chinese: 蘭嶼; pinyin: Lányǔ). It is also known in Taiwanese Hokkien Chinese: 蘭嶼; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Lân-sū.

The island had previously been known to the Chinese as "Redhead Island" (Mandarin Chinese: 紅頭嶼; pinyin: Hóngtóuyǔ; Taiwanese Hokkien Chinese: 紅頭嶼; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Âng-thâu-sū), referring to the island's northwestern mountain peaks, which resemble red human heads when illuminated by the setting sun.[7] These characters were borrowed into Japanese as Kōtōsho during their rule of Taiwan.[8]

History

Prehistory

Based on genetic studies, Orchid Island was settled by the ancestors of the Tao people during the Austronesian Expansion (approximately 4000 BP) from the mainland of Taiwan. They maintained close contact through trade and intermarriage with the Ivatan people of the neighboring Batanes Islands of the Philippines until the beginning of the Colonial Era.[9]

Great Qing

The island first appears on surviving charts in the 17th century, when it was noted by Japanese sailors.

The island was visited by a surveying party from HMS Sylvia in 1867. In the early 1870s, William Campbell saw the island from aboard the Daphne, and wrote:[10]

We had a very stormy passage, so much so, that my servant boy and the Chinese preacher (Chiu Paw-ha) who accompanied me, were dead sick during the seven days we were at sea. While laboring off the Island of Botel Tobago, our mainsail was torn in pieces ; and, for several days, every other great sea we faced threatened to engulf us. I was sorry for the poor ship-hands, who had to work hard, and be content with mere snatches of time for food and sleep. It was only through repeated drenchings, and with firm holding on, that I succeeded in getting a good look at the land which came now and then into view. Every one was interested as we approached Botel Tobago. The last European visit to it was by a surveying party from H.M.S. Sylvia in 1867. It stands about twenty-six miles out from the south-eastern end of Formosa, is seven and a half miles long, and densely peopled by an aboriginal race. We saw their huts, and could make out rows of little canoes or rafts drawn up on the beach.

Imperial Japan

During Japan's rule of Taiwan, its government declared Kōtō Island an ethnological research area off-limits to the general public.

Republic of China

After the Republic of China took over Taiwan, the island was administered as the Hong-tou-yu "township" of Taitung County after 19 January 1946 but the Japanese restrictions on visitors remained in effect. Because of these policies, the Tao continue to have the best-preserved traditions among the Taiwanese aborigines[11] despite the end of the ban on settlement and tourism in 1967.

Since 1967, schools have been built on the island and education in Mandarin is compulsory.

Lesser Orchid Island has been used for target practice drills by the Republic of China Air Force.[when?][citation needed]

A nuclear-waste storage facility was built in 1982 without prior consultation with the island's inhabitants. Tao Aborigines have protested, and since the early 1990s demonstrated, their desire to rid their island of the "evil spirits" of nuclear waste.[12] The plant receives nuclear waste from Taiwan's three nuclear power plants, all operated by the state utility Taipower. About 100,000 barrels of nuclear waste have been stored at the Lanyu complex.[13] In 2002 and 2012, there were major protests from local residents, calling on Taipower to remove the waste from the island.[14]

Geography

There are eight mountains over 400 m (1,300 ft) high. The tallest mountain is Mount Hongtou or Hongtoushan (紅頭山) at 552 m (1,811 ft). The rock on the island is volcanic tholeiite andesite and explosive fragments. The volcano last erupted in the Miocene period. It is part of the Luzon Volcanic Arc. Magma was formed from underthrusting oceanic crust under compression about 20 km (12 mi) deep. The andesite rock contains some visible crystals of pyroxene or amphibole. The geochemistry of the rock shows that it is enriched in sodium, magnesium, and nickel but depleted in iron, aluminum, potassium, titanium, and strontium.[15]

As the island is within the tropics, the island experiences a warm and rainy tropical climate throughout the year with humidity often reaching more than 90%. Rainfall, abundant throughout the year, cools the temperature significantly. The climate is classified as a monsoon-influenced Köppen's tropical rainforest climate (Af) with frequent cyclones therefore not equatorial, with annual temperatures averaging around 23 °C (73 °F) on the mountains and 26 °C (79 °F) on the coasts, one of the highest in Taiwan.

Lesser Orchid Island is an uninhabited volcanic islet nearby. It is the southernmost point of Taitung County. It is home to a critically endangered endemic[citation needed] orchid, Phalaenopsis equestris f. aurea.

Forest Belle Rock is located south of Lesser Orchid Island.[16]

| Climate data for Lanyu Weather Station – 324 m above sea level (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1942–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 27.3 (81.1) |

29.3 (84.7) |

29.8 (85.6) |

32.1 (89.8) |

32.1 (89.8) |

33.1 (91.6) |

33.1 (91.6) |

35.2 (95.4) |

32.2 (90.0) |

31.1 (88.0) |

29.8 (85.6) |

28.5 (83.3) |

35.2 (95.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 20.8 (69.4) |

21.4 (70.5) |

22.9 (73.2) |

24.8 (76.6) |

26.7 (80.1) |

28.0 (82.4) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.5 (83.3) |

27.7 (81.9) |

25.9 (78.6) |

23.9 (75.0) |

21.5 (70.7) |

25.1 (77.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 18.6 (65.5) |

19.0 (66.2) |

20.4 (68.7) |

22.3 (72.1) |

24.3 (75.7) |

25.9 (78.6) |

26.2 (79.2) |

26.0 (78.8) |

25.3 (77.5) |

23.7 (74.7) |

21.9 (71.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

22.8 (73.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 17.0 (62.6) |

17.4 (63.3) |

18.7 (65.7) |

20.7 (69.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.3 (75.7) |

23.6 (74.5) |

22.3 (72.1) |

20.5 (68.9) |

18.1 (64.6) |

21.2 (70.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 9.2 (48.6) |

9.5 (49.1) |

10.3 (50.5) |

11.3 (52.3) |

16.1 (61.0) |

17.6 (63.7) |

20.2 (68.4) |

19.3 (66.7) |

13.3 (55.9) |

14.1 (57.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

9.2 (48.6) |

9.2 (48.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 249.9 (9.84) |

190.7 (7.51) |

135.2 (5.32) |

142.9 (5.63) |

247.2 (9.73) |

245.8 (9.68) |

252.0 (9.92) |

328.8 (12.94) |

361.1 (14.22) |

299.0 (11.77) |

282.6 (11.13) |

243.5 (9.59) |

2,978.7 (117.28) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 22.0 | 18.4 | 16.1 | 14.3 | 15.1 | 13.7 | 14.9 | 16.9 | 18.4 | 18.2 | 19.9 | 21.7 | 209.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85.6 | 86.6 | 86.4 | 88.2 | 89.0 | 90.2 | 89.4 | 89.5 | 86.6 | 85.8 | 86.4 | 85.3 | 87.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 73.3 | 73.5 | 96.9 | 109.7 | 127.7 | 142.4 | 179.1 | 158.2 | 136.7 | 125.7 | 81.6 | 64.3 | 1,369.1 |

| Source: Central Weather Bureau[17][18][19][20][21] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Lanyu Weather Station – Ground level | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 24.1 (75.4) |

24.6 (76.3) |

26.3 (79.3) |

28.1 (82.6) |

30.2 (86.4) |

31.0 (87.8) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.3 (90.1) |

31.7 (89.1) |

29.8 (85.6) |

27.4 (81.3) |

24.8 (76.6) |

28.5 (83.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 21.8 (71.2) |

22.5 (72.5) |

24.0 (75.2) |

25.8 (78.4) |

27.9 (82.2) |

29.2 (84.6) |

29.5 (85.1) |

29.3 (84.7) |

28.6 (83.5) |

27.3 (81.1) |

25.1 (77.2) |

22.8 (73.0) |

26.2 (79.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 20.2 (68.4) |

20.6 (69.1) |

22.2 (72.0) |

24.1 (75.4) |

25.3 (77.5) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.6 (81.7) |

26.8 (80.2) |

25.5 (77.9) |

23.5 (74.3) |

21.3 (70.3) |

24.4 (75.9) |

| Source: Lanyu Weather Accuweather | |||||||||||||

Administrative divisions

There are seven neighborhoods (社) in Lanyu Township, four of which are also administrative villages (村):

| Yami name | Chinese | Note | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pinyin | Chars. | ||

| Jiayo | Yeyou | 椰油 | village |

| Jiraralay | Langdao | 朗島 | village |

| Jiranmilek | Dongqing | 東淸 | village |

| Jivalino | Yeyin | 野銀 | |

| Jimowrod | Hongtou | 紅頭 | village and township seat |

| Jiratay | Yuren | 漁人 | incorporated into Hongtou Village in 1946 |

| Iwatas | Yiwadasi | 伊瓦達斯 | incorporated into Yeyou Village in 1940 |

Flora and fauna

Orchid Island hosts many tropical plant species, sharing many species with tropical Asia but also many endemics: there are 35 plant species found nowhere else.[22] For example, Pinanga tashiroi is a species of palm tree found nowhere else than Orchid Island.[23]

Green sea turtles make nests on the island,[24] which is surrounded by coral reefs.[25] Four species of sea snake inhabit the waters around the island.[26] Humpback whales were historically common in the area,[27] and there were continuous sightings of them in the 2000s,[28] which marked the first return of the species into Taiwanese waters since the cessation of whaling.[29] Sightings are reported almost every year, although the whales do not stay for long, as they once did. They appear instead to be migratory visitors.[30]

Demographics

Out of a total current population of 5036,[when?] approximately 4200 belong to the indigenous Tao people and the remaining 800 are mainly Han Chinese.[citation needed]

Economy

The islanders are mostly farmers and fishermen relying on a large annual catch of flying fish and on wet taro, yams, and millet.

On 19 September 2014, the first 7-Eleven store in the island was opened. During the opening ceremony, the township chief said that the store could provide conveniences to the local residents such as fee and tax collection.[31]

Energy

Nuclear waste

The Lanyu nuclear waste storage facility was built at the southern tip of Orchid Island in 1982. The plant receives nuclear waste from Taiwan's three nuclear power plants operated by state utility Taiwan Power Company (Taipower). Islanders did not have a say in the decision to locate the facility on the island.[13]

In 2002, almost 2000 protesters, including many residents and elementary and high school students from the island, staged a sit-in in front of the storage plant, calling on Taipower to remove nuclear waste from the island. The government had pledged and then failed to withdraw the 100,000 barrels of waste from their island by the end of 2002.[13][32] Aboriginal politicians successfully obstructed legislative proceedings that year to show support for the protests.[33] In a bid to allay safety concerns, Taipower has pledged to repackage the waste since many of the iron barrels used for storage have become rusty from the island's salty and humid air. Taipower has for years been exploring ways to ship the nuclear waste overseas for final storage, but plans to store the waste in an abandoned North Korean coal mine have met with strong protests from neighboring South Korea and Japan due to safety and environmental concerns, while storage in Russia or China is complicated by political factors. Taipower is "trying to convince the islanders to extend the storage arrangement for another nine years in exchange for payment of NT$200 million (about $5.7 million)".[13]

Following years of protests by residents, more concerns arose about the facility after Japan's Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011. A report released in November 2011 said a radioactive leak had been detected outside the facility and this has added to residents' concerns. In February 2012, hundreds of Tao living on Orchid Island held a protest outside the nuclear waste storage facility.[14] Chang Hai-yu, a preacher at a local church, said "it was a tragedy that Tao children are being born into a radiation-filled environment". Lanyu mayor Chiang To-li "urged Taipower to remove nuclear waste from the island as soon as possible".[14]

In March 2012, about 2,000 people staged an anti-nuclear protest in Taiwan's capital Taipei. Scores of aboriginal protesters "demanded the removal of 100,000 barrels of nuclear waste stored on Orchid Island, off south-eastern Taiwan. Authorities have failed to find a substitute storage site amid increased awareness of nuclear danger over the past decade".[34][35]

Power generation

The island houses its only power generation facility, the fuel-fired Lanyu Power Plant. Commissioned in 1982, the plant has a total installed capacity of 6.5 MW and is owned and operated by Taipower. Stipulated under Article 14 of the Offshore Islands Development Act, households on the island enjoy free electricity. The situation on the island resulted from the preferential policy given to the island residents due to the construction of the Lanyu Storage Site on the island in 1982.[36][37]

Due to the free electricity, electricity consumption on the island is generally much higher than in other parts of Taiwan. In 2011, the average annual electricity consumption per household in Lanyu was 6,522 kWh, almost twice the 3,654 kWh Taiwan average. In 2002, Taipower provided an equivalent of NT$6.35 million worth of electricity to the island, and in 2011 the amount rose to NT$24.39 million. Due to this suspected abuse, members of Control Yuan called for an investigation into the electricity subsidy to Lanyu Island in 2012.[38]

Tourist attractions

Transport

The island is accessible by sea or air. Daily Air offers flights from Taitung Airport in Taitung City to Lanyu Airport on Orchid Island. The flight duration is half an hour and the daily frequency is dependent on weather conditions. Ferry trips to the island are available from Taitung City's Fugang Fishery Harbor year round. In the summer, there is a ferry from Houbihu port in Kenting.

Gallery

- Langdao beach

- Traditional canoe

- Lovers' Cave near Iranmeylek

- Fields along the coast

- Mantou Rock

- Old anti-Communist slogan

- Traditional Tao building

- Tao fishermen in 1900

See also

- Green Island – the other offshore township of Taitung County

- List of islands of Taiwan

- List of volcanoes in Taiwan

References

Citations

- ^ Stöpel, Karl Theodor (1905). Eine Reise in das Innere der Insel Formosa (in German).

- ^ RICK CHARETTE (November 2019). "Surf and Turf With Indigenous Influences". Travel in Taiwan. Tourism Bureau, MOTC. p. 39.

Orchid Island (Lanyu) 蘭嶼

- ^ Rau, Victoria (2015). "A Yami language teacher's journey in Taiwan". In Volker, Crag Alan; Anderson, Fred E. (eds.). Education in Languages of Lesser Power: Asia-Pacific Perspectives (PDF). John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 9789027218766.

- ^ a b A 1654 map.[clarification needed]

- ^ a b Campbell (1896), map.

- ^ "Renshi Lanyu". Lanyu Township Office. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ Tourism Bureau, Republic of China (Taiwan) (2008-04-30). "Tourism Bureau, Republic of China (Taiwan)-Taitung County". Tourism Bureau, Republic of China (Taiwan). Retrieved 2020-04-23.

- ^ "Koto-Sho, Formosa" 1:50,000 AMS Series L792 map, United States Army Corps of Engineers, 1944

- ^ Loo, Jun-Hun; Trejaut, Jean A; Yen, Ju-Chen; Chen, Zong-Sian; Lee, Chien-Liang; Lin, Marie (2011). "Genetic affinities between the Yami tribe people of Orchid Island and the Philippine Islanders of the Batanes archipelago". BMC Genetics. 12 (1): 21. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-12-21. PMC 3044674. PMID 21281460.

- ^ William Campbell (1915). "Sketches from Formosa". pp. 46–47.

- ^ "Taiwan's indigenous peoples portal".

- ^ Han Cheung (19 February 2017). "Taiwan in Time: Chasing away 'evil spirits'". Taipei Times. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Orchid Island launches new protests against nuclear waste". Asian Economic News. May 6, 2002.

- ^ a b c Loa Iok-sin (21 February 2012). "Tao protest against nuclear facility". Taipei Times.

- ^ Zhang Jinhai; He Lishi (2002). "Geology of Taiwan Province". Geology of China. Geological Publishing House. ISBN 978-7-116-02268-3.

- ^ George Leslie MacKay (1896). From far Formosa : the island, its people and missions. Chicago: Fleming H. Revell Company. p. 40.

Forest Belle Rk.

- ^ "Monthly Mean". Central Weather Bureau. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ "氣象站各月份最高氣溫統計" (PDF) (in Chinese). Central Weather Bureau. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ "氣象站各月份最高氣溫統計(續)" (PDF) (in Chinese). Central Weather Bureau. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ "氣象站各月份最低氣溫統計" (PDF) (in Chinese). Central Weather Bureau. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ "氣象站各月份最低氣溫統計(續)" (PDF) (in Chinese). Central Weather Bureau. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ Hsieh, Chang-Fu (2002). "Composition, endemism and phytogeographical affinities of the Taiwan flora". Taiwania. 47: 298–310.

- ^ Liao, Jih-Ching (2000). "Palmae (Arecaceae)". In Huang, Tseng-chieng (ed.). Flora of Taiwan. Vol. 5 (2nd ed.). Taipei, Taiwan: Editorial Committee of the Flora of Taiwan, Second Edition. pp. 655–662. ISBN 978-957-9019-52-1. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ^ Cheng, I-Jiunn; Cheng-Ting Huang; Po-Yen Hung; Bo-Zong Ke; Chao-Wei Kuo; Chia-Ling Fong (2009). "Ten years of monitoring the nesting ecology of the green turtle, Chelonia mydas, on Lanyu (Orchid I.), Taiwan" (PDF). Zoological Studies. 48 (1): 83–94.

- ^ Dai, C.-F. (1991). "Reef environment and coral fauna of southern Taiwan" (PDF). Atoll Research Bulletin. 354: 1–24. doi:10.5479/si.00775630.354.1.

- ^ Tu, M. C.; M. C. Tu, S. C. Fong and K. Y. Lue (1990). "Reproductive biology of the sea snake, Laticauda semifasciata, in Taiwan". Journal of Herpetology. 24 (2): 119–126. doi:10.2307/1564218. JSTOR 1564218.

- ^ "Deep-water serenader gives local performance – Taiwan Today". Archived from the original on 2016-03-11. Retrieved 2016-03-02.

- ^ (utmost), utmost (5 January 2011). "2011 鯨年要做的事 @ ARKILA :: 痞客邦 PIXNET".

- ^ "尋鯨記".

- ^ 滔滔 - Ocean says, 2015, 追逐鯨魚的人:專訪台灣第一位水下鯨豚攝影師金磊

- ^ "7-Eleven opens on Orchid Island – Taipei Times". www.taipeitimes.com. 20 September 2014.

- ^ Hsu, Crystal (10 April 2002). "Yu apologizes for island's nuclear woes". Taipei Times. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ Hsu, Crystal (4 May 2002). "Aborigine lawmakers make good on threat". Taipei Times. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ "About 2,000 Taiwanese stage anti-nuclear protest". Straits Times. 11 March 2011.

- ^ "Taiwan – Standing on Shaky Ground". 9 April 2013 – via www.abc.net.au.

- ^ "Lanyu residents accused of abusing free electricity|Society|News|WantChinaTimes.com". Archived from the original on 2014-10-13. Retrieved 2014-10-08.

- ^ "Offshore Islands Development Act". Laws & Regulations Database of The Republic of China.

- ^ "The China Post". The China Post.

Bibliography

- Campbell, William (1896), "The Island of Formosa: Its Past and Future", Scottish Geographical Magazine, vol. 12, pp. 385–399, doi:10.1080/00369229608732903.

Further reading

- Martinson, Barry (2016), Song of Orchid Island (2nd ed.), Camphor Press

- Badaiwan de Shenhua 《八代灣的神話》 (Myths from Ba-dai Bay). Taipei: Morning Star Publishing Co., 1992.—Syaman Rapongan's first book; a collection of myths and his personal reflections on contemporary Tao; divided into two parts, with the first on myths, and the second on personal reflections.

- Lenghai Qing Shenhaiyang Chaosheng Zhe 《冷海情深—海洋朝聖者》(Deep Love for Cold Sea: The Oceanic Pilgrim). Taipei: Unitas Publishing Co., Ltd., 1997.—A collection of short stories about Syaman Rapongan's life on Lanyu; the book marks the writer's constant struggles with himself and his family because he voluntarily went unemployed and devoted himself solely to the ocean as a bare-hand diver in order to explore Tao civilization and find the meaning of life. The book also marks the writer's initial identity transition from a Sinicized man to a real Tao who embraces the value of physical labor and learns to cultivate the art of story-telling. The book was the Annual Reading for 1997 by United Daily News.

- Heise de Chibang 《黑色的翅膀》 (Black Wings). Taipei: Morning Star Publishing Co., 1999.—Syaman Rapongan's first novel; it questions the future of Tao people through the characterization of four young men (Kaswal, Gigimit, Jyavehai and Ngalolog) Should they run rigorously after the tempting ‘white body’ on the land or wait patiently for the arrival of ‘black wings’ on the sea? Although this appears a rhetorical question, Syaman Rapongan reveals that the conflicts are severe and their impact profound. This novel won Wu Zhuo-liou Literary Award in 1999.

- Hailang de Jiyi 《海浪的記憶》 (Memory of the Ocean Waves). Taipei: Unitas Publishing Co., Ltd., 2002.—Another collection of short stories; divided into two parts, with the first on the countless ties between Tao and the sea (six stories), and the second on Tao's staunch fights against foreign influences. Experimenting boldly with different genre and languages, the writer combines verses with prose and juxtaposes Tao and Chinese languages. As another Taiwanese writer and critic, Song Ze-lai, points out, Syaman Rapongan deliberately defamiliarizes his language and syntax in order to praise traditional Tao values and to guide his readers, especially Tao, back to the original way of living, far from influences of Chinese culture and modern civilization.

- Hanghaijia de Lian 《航海家的臉》 (The Face of a Navigator). Taipei: INK Literary Publishing Co., 2007.—Also a collection of articles; it continues the oceanic theme but exposes more of Syaman Rapongan's personal battles with modernity or traditionality and his pursuit of prosperity or return to innocence. Calling him-self a nomadic soul, Syaman Rapongan knows there may be no end to his battle. His course is a romantic one, without any definite plan. Nor will his beloved sea offer any answer or guidance. Nevertheless, consolation can be found in sweet solitude and family understanding. Syaman Rapongan's first attempt at trans-Pacific navigation with a Japanese captain and five Indonesian crew members is also included here.

- Lao Hairen 《老海人》 (Old Ama Divers). Taipei: INK Literary Publishing Co., Ltd., 2009.—Syaman Rapongan's second novel; highly praised and awarded (The Wu Lu-chin Prize for Essays, Chiu Ko Publishing Co. Annual Selection in 2006). Instead of following the previous semi-biographical direction, Syaman Rapongan focuses on three outcasts on his island, Ngalomirem, Tagangan and Zomagpit, whose pretty names fail to bring them pretty lives. Ngalomiren is regarded as a psychopath, Tagangan a miserable student though a brilliant octopus-catcher, and Zomagpit a hopeless drunkard. Through these figures, Syaman Rapongan portrays how Tao society stumbles between traditionality and modernity, and how broken the society has become in both material and mental terms as its humble and simple way becomes recognized again. In spite of a slight hope for reconciliation, this way back to the humble and simple Tao world is arduous, sometimes painful, and fully filled with regrets.

External links

- Taiwan Aborigine Monograph Series 2

- Taipei Multicultural Arts Group

- Cultural Survival on Orchid Island

- Some information and pictures about the island

- Taipower, North Korea strike accord on nuke waste storage

- Orchid Island: Taiwan's nuclear dumpsite

- Syaman Rapongan, Taiwan's Ocean Literature Writer

- BBC News: Taiwan's paradise island fights to save its identity

- A subaqueous loner — Syaman Rapongan