Labor camp

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

A labor camp (or labour camp, see spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have many common aspects with slavery and with prisons (especially prison farms). Conditions at labor camps vary widely depending on the operators. Convention no. 105 of the United Nations International Labour Organization (ILO), adopted internationally on 27 June 1957, intended to abolish camps of forced labor.[1]

In the 20th century, a new category of labor camps developed for the imprisonment of millions of people who were not criminals per se, but political opponents (real or imagined) and various so-called undesirables under communist and fascist regimes.

Precursors

Early-modern states could exploit convicts by combining prison and useful work in manning their galleys.[2] This became the sentence of many Christian captives in the Ottoman Empire[3] and of Calvinists (Huguenots) in pre-Revolutionary France.[4]

20th century

Albania

Allies of World War II

- The Allies of World War II operated a number of work camps after the war. At the Yalta Conference in 1945, it was agreed that German forced labor was to be utilized as reparations. The majority of the camps were in the Soviet Union, but more than one million Germans were forced to work in French coal-mines and British agriculture, as well as 500,000 in US-run Military Labor Service Units in occupied Germany itself.[5] See Forced labor of Germans after World War II.

Bulgaria

Burma

- According to the New Statesman, Burmese military government operated, from 1962 to 2011, about 91 labour camps for political prisoners.[6]

China

- The anti-communist Kuomintang operated various camps between 1938 and 1949, including the Northwestern Youth Labor Camp for young activists and students.[7]

- The Chinese Communist Party has operated many labor camps for some crimes at least since taking power in 1949. Many leaders of China were put into labor camps after purges, including Deng Xiaoping and Liu Shaoqi. May Seventh Cadre Schools are an example of Cultural Revolution-era labor camps.

Cuba

- Beginning in November 1965, people classified as "against the government" were summoned to work camps referred to as "Military Units to Aid Production" (UMAP).[8]

Czechoslovakia

- After the communists took over Czechoslovakia in 1948, many forced labor camps were created.[citation needed] The inmates included political prisoners, clergy, kulaks, Boy Scout leaders and many other groups of people that were considered enemies of the state.[citation needed] About half of the prisoners worked in the uranium mines.[9] These camps lasted until 1961.[citation needed]

- Also between 1950 and 1954 many men were considered "politically unreliable" for compulsory military service, and were conscripted to labour battalions (Czech: Pomocné technické prapory (PTP)) instead.[citation needed]

Communist Hungary

- Following sentence, political prisoners were imprisoned. To serve this purpose, a large number of internment camps (e.g., in Kistarcsa, Recsk (Recsk forced labor camp), Tiszalök, Kazincbarcika and according to the latest research, in Bernátkút and Sajóbábony) were placed under the supervision of the State Protection Authority. [10] The most notorious of these camps were in Recsk, Kistarcsa, Tiszalök and Kazincbarcika. [11]

Italian Libya

- During the colonisation of Libya the Italians deported most of the Libyan population in Cyrenaica to concentration camps and used the survivors to build in semi-slave conditions the coastal road and new agricultural projects.[12]

Germany

- During World War II the Nazis operated several categories of Arbeitslager (Labor Camps) for different categories of inmates. The largest number of them held Jewish civilians forcibly abducted in the occupied countries (see Łapanka) to provide labor in the German war industry, repair bombed railroads and bridges or work on farms. By 1944, 19.9% of all workers were foreigners, either civilians or prisoners of war.[13]

- The Nazis employed many slave laborers. They also operated concentration camps, some of which provided free forced labor for industrial and other jobs while others existed purely for the extermination of their inmates. A notable example is the Mittelbau-Dora labor camp complex that serviced the production of the V-2 rocket. See List of German concentration camps for more.

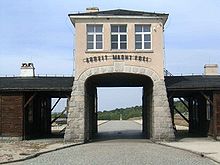

- The Nazi camps played a key role in the extermination of millions. The phrase Arbeit macht frei ("Work makes one free") has become a symbol of The Holocaust.

Imperial Japan

- During the early 20th century, the Empire of Japan used the forced labor of millions of civilians from conquered countries and prisoners of war, especially during the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Pacific War, on projects such as the Death Railway. Hundreds of thousands of people died as a direct result of the overwork, malnutrition, preventable disease and violence which were commonplace on these projects.

North Korea

- North Korea is known to operate six camps with prison-labor colonies for political criminals (Kwan-li-so). The total number of prisoners in these colonies is 150,000 to 200,000. Once condemned as a political criminal in North Korea, the defendant and his/or her family are incarcerated for life in one of the camps without trial and cut off from all outside contact.[14]

- See also: North Korean prison system

Romania

Russia and the Soviet Union

- Imperial Russia operated a system of remote Siberian forced labor camps as part of its regular judicial system, called katorga.

- The Soviet Union took over the already extensive katorga system and expanded it immensely, eventually organizing the Gulag to run the camps. In 1954, a year after Stalin's death, the new Soviet government of Nikita Khrushchev began to release political prisoners and close down the camps. By the end of the 1950s, virtually all "corrective labor camps" were reorganized, mostly into the system of corrective labor colonies. Officially, the Gulag was terminated by the MVD order 20 of January 25, 1960.[15]

- During the period of Stalinism, the Gulag labor camps in the Soviet Union were officially called "Corrective labor camps". The term "labor colony"; more exactly, "Corrective labor colony", (Russian: исправительно-трудовая колония, abbr. ИТК), was also in use, most notably the ones for underaged (16 years or younger) convicts and captured besprizorniki (street children, literally, "children without family care"). After the reformation of the camps into the Gulag, the term "corrective labor colony" essentially encompassed labor camps.[citation needed]

Russian Federation

Sweden

- 14 labor camps were operated by the Swedish state during World War II. The majority of internees were communists, but radical social democrats, syndicalists, anarchists, trade unionists, anti-fascists and other "unreliable elements" of Swedish society, as well as German dissidents and deserters from the Wehrmacht, were also interned. The internees were placed in the labor camps indefinitely, without trial, and without being informed of the accusations made against them. Officially, the camps were called "labor companies" (Swedish: arbetskompanier). The system was established by the Royal Board of Social Affairs and sanctioned by the third cabinet of Per Albin Hansson, a grand coalition which included all parties represented in the Swedish Riksdag, with the notable exception of the Communist Party of Sweden.

- After the war, many former camp inmates had difficulty finding a job, since they had been branded as "subversive elements".[16]

Turkey

United States

- During the United States occupation of Haiti, the United States Marine Corps and their Gendarmerie of Haiti subordinates enforced a corvée system upon Haitians.[17][18][19] The corvée resulted in the deaths of hundreds, and possibly thousands, of Haitians, with Haitian American academic Michel-Rolph Trouillot estimating that about 5,500 Haitians died in labor camps.[20] In addition, Roger Gaillard writes that some Haitians were killed fleeing the camps or if they did not work satisfactorily.[21]

Vietnam

Yugoslavia

- The Goli Otok prison camp for political opponents ran from 1946 to 1956.

21st century

China

- The Standing Committee of the National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China, which closed on December 28, 2013, passed a decision on abolishing the legal provisions on reeducation through labor. However, penal labor allegedly continues to exist in Xinjiang internment camps.[22][23][24][25][26]

North Korea

- North Korea is known to operate six camps with prison-labor colonies for political criminals (Kwan-li-so). The total number of prisoners in these colonies is 150,000 – 200,000. Once condemned as a political criminal in North Korea, the defendant and their families are incarcerated for lifetime in one of the camps without trial, and are cut off from all outside contact.[14]

United States

- In 1997, a United States Army document was developed that "provides guidance on establishing prison camps on [US] Army installations."[27]

See also

References

- ^ Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements: G to M, Routledge - New York, London, 1 January 2003, retrieved 19 July 2024

- ^

Gibson, Mary; Poerio, Ilaria (2018). "Modern Europe, 1750–1950". In Anderson, Clare (ed.). A Global History of Convicts and Penal Colonies. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1350000698. Retrieved 2019-10-07.

A second early modern form of punishment, the galleys, constituted a more direct precedent to the earliest hard labour camps. [...] Galley rowing offered no promise of rehabilitation and, in fact, often led to disease and death. However, it shared with the prison workhouses of northern Europe a new aspiration to integrate hard labour into punishment for the eeconomic benefit of the state.

- ^

Magocsi, Paul Robert (1996). A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples (2nd ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press (published 2010). p. 185. ISBN 978-1442698796. Retrieved 2019-10-07.

And what happened to the captives from Ukraine [...]? The slaves functioned at all levels of Ottoman society [...]. At the lowest end of the social scale were galley slaves conscripted into the imperial naval fleet and field hands who labored on Ottoman landed estates.

- ^

van Ruymbeke, Bertrand (2005). "'A Dominion of True Believers Not a Republic for Heretics': French Colonial Religious Policy and the Settlement of Early louisiana, 1699–1730". In Bond, Bradley G. (ed.). French Colonial Louisiana and the Atlantic World. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0807130353. Retrieved 2019-10-07.

Andre Zysberg's study shows that [...] nearly 1,500 Huguenots were sentenced to the galleys between 1680 and 1716 [...].

- ^ John Dietrich, The Morgenthau Plan: Soviet Influence on American Postwar Policy (2002) ISBN 1-892941-90-2

- ^ "Burma's forced labour". www.newstatesman.com. 9 June 2008.

- ^ Mühlhahn, Klaus (2009). Criminal Justice in China: A History. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press ISBN 978-0-674-03323-8. pp. 132–133.

- ^ "A book sheds light on a dark chapter in Cuban history" Archived 2009-11-03 at the Wayback Machine, El Nuevo Herald, January 19, 2003. (in Spanish)

- ^ Sivoš, Jerguš. "Tábory Nucených Prací (TNP) v Československu" (in Czech). totalita.cz. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ^ From secret interrogations to the “Vatican” of transit prison

- ^ Internment

- ^ General History of Africa, Albert Adu Boahen, Unesco. International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa, p. 196, 1990

- ^ Herbert, Ulrich (2000). "Forced Laborers in the Third Reich: An Overview (Part One)" (PDF). International Labor and Working-Class History. 58. doi:10.1017/S0147547900003677. S2CID 145344942. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-09. (offprint)

- ^ a b "The Hidden Gulag – Part Two: Kwan-li-so Political Panel Labor Colonies" (PDF). The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea. pp. 25–82. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ^ "Система исправительно-трудовых лагерей в СССР". old.memo.ru.

- ^ Berglund, Tobias; Sennerteg, Niclas (2008). Svenska koncentrationsläger i Tredje rikets skugga. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur. ISBN 978-9127026957.

- ^ Alcenat, Westenly. "The Case for Haitian Reparations". Jacobin. Retrieved 2021-02-20.

- ^ "U.S. Invasion and Occupation of Haiti, 1915–34". United States Department of State. 2007-07-13. Retrieved 2021-02-24.

- ^ Paul Farmer, The Uses of Haiti (Common Courage Press: 1994)

- ^ Belleau, Jean-Philippe (2016-01-25). "Massacres perpetrated in the 20th Century in Haiti". Sciences Po. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- ^ Belleau, Jean-Philippe (2016-01-25). "Massacres perpetrated in the 20th Century in Haiti". Sciences Po. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- ^ Finley, Joanne Smith (2022-09-01). "Tabula rasa: Han settler colonialism and frontier genocide in "re-educated" Xinjiang". HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory. 12 (2): 341–356. doi:10.1086/720902. ISSN 2575-1433. S2CID 253268699.

- ^ Clarke, Michael (2021-02-16). "Settler Colonialism and the Path toward Cultural Genocide in Xinjiang". Global Responsibility to Protect. 13 (1): 9–19. doi:10.1163/1875-984X-13010002. ISSN 1875-9858. S2CID 233974395.

- ^ Byler, Darren (2021-12-10). Terror Capitalism: Uyghur Dispossession and Masculinity in a Chinese City. Duke University Press. doi:10.1215/9781478022268. ISBN 978-1-4780-2226-8. JSTOR j.ctv21zp29g. S2CID 243466208.

- ^ Byler, Darren (2021). In the Camps: China's High-Tech Penal Colony. Columbia Global Reports. ISBN 978-1-7359136-2-9. JSTOR j.ctv2dzzqqm.

- ^ Lipes, Joshua (November 12, 2019). "Expert Estimates China Has More Than 1,000 Internment Camps For Xinjiang Uyghurs". Radio Free Asia. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- ^ "US Army Civilian Inmate Labor Program" (PDF). Army.mil. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2003-04-03.

External links

Media related to Communist labour camps at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Communist labour camps at Wikimedia Commons Media related to Concentration camps at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Concentration camps at Wikimedia Commons