L. Smit en Zoon

Shipyard L. Smit to the right of J. & K. Smitd | |

| Industry | Shipbuilding |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1791 |

| Fate | Merged into IHC Holland in 1965 |

| Headquarters | , |

Key people | Fop Smit, L. Smit |

| Products | Dredging vessels, Inland navigation ships |

L. Smit en Zoon previously known as Fop Smit, was a Dutch shipbuilding company located in Kinderdijk. Its successor is now part of Royal IHC.

Context

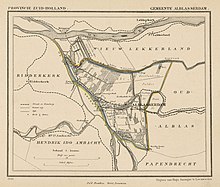

L. Smit en Zoon shipyard was one of multiple shipyards belonging to the Smit family. In 1785 Jan Smit Fopszoon (1742–1807)[1] and his brother Jacques Smit Fopszoon (1756–1820)[2] took over a shipyard in Alblasserdam, near the border with Nieuw-Lekkerland.

After they were established, Jacques built another shipyard west of the one they had, at the terrain later known as that of L. Smit en Zoon.[3] Jan Smit Fopszoon was very successful in building a small type of vessel, the hoogaars On his death, Jan Smit Fopszoon was wealthy. He had two shipyards, several houses, 18 hectares of land multiple (parts in) ships, as well as many securities. With Marrigje Ceelen (1747–1820) he had three sons and two daughters:[4]

- Fop Smit (1777–1866)

- Jan Smit (1779–1869) inherited his father's shipyard in Alblasserdam, and worked in partnership with Fop from 1824 to 1828, his sons founded J. & K. Smit

- Cornelis Smit (1784–1858) Founded his own shipyards Jan Smit Czn. near the harbor of Alblasserdam and in Zierikzee, and had a patent slip in Papendrecht.[5]

Fop Smit, or more exactly Fop Smit Janszoon (11 October 1777 – 25 August 1866)[1] took over the shipyard of his uncle Jacques Smit Fopszoon, and thus founded the shipyard Fop Smit, later known as L. Smit en Zoon.[3]

Fop Smit married Jannigje Mak (1776–1852) and had:[1]

- Pieter Smit (1808–1863), father of Pieter Smit Jr. (1848–1913)

- Jan Smit (1811–1875), father of Jan Smit V (1837- ?) and Arie Smit (1845–1925)

- Leendert Smit (1813–1893)[6][7]

- Fop Smit Jr. (1815–1892)

Jan Smit a.k.a. Jan Smit Fopszoon would later lead a shipyard at Slikkerveer, which was probably split off from Fop Smit's shipyard. He would be succeeded by his son Arie Smit.[8]

Leendert Smit continued to work at his father's shipyard, and would continue it as L. Smit en Zoon. He would be joined by his nephew Jan Smit V, who had married his daughter Jannetje Johanna (1838-?).[8]

History as Fop Smit's shipyard

Separate shipyards of Jan and Foppe

From 1807 to 1820 Jan Smit Fopszoon's second son Jan Smit and his mother continued his shipyard, which had about 10 employees. Afterwards Jan continued alone. Meanwhile, Fop acquired the shipyard of Jacques Smit Fopszoon (1756–1820). Until 1824 the shipyards of Fop Smit and Jan Smit continued to build only built small vessels.[9]

United shipyards of Fop and Jan

In 1824 Jan Smit contracted to build the paddle steamer Willem de Eerste for a shipping line between Rotterdam and Nijmegen. The engines were made by Billard in Jemappes.[10] It was probably on account of this project that Fop and Jan entered into a partnership.[9]

On 9 May 1825 the first Batavier was laid down by Fop Smit for an Amsterdam Hamburg line managed by the Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij (NSM, later NSBM). The engines would be built by John Cockerill in Liège.[11] Also for NSM, Fop Smit launched the steam vessel Lodewijk on 15 March 1826. It would be used for service between Mainz and Strasbourg[12] On 14 November 1826 the brothers laid down for their own account the Kinderdijk, a 380 tons Kofschip.[13] She was launched on 24 May 1828.[14] A Kofschip was a most often two-masted vessel meant for coastal shipping. Kinderdijk's hull was sheathed in zinc.[15]

The shipbuilding partnership between Fop and Jan Smit did not last long. Jan left it, and rented his part of the shipyard to Fop.[9] Fop Smit thus continued alone, but with both terrains. On 28 November 1828 Fop Smit laid down a two-deck commercial frigate of 34.2 m length.[16] This might have been Vier Gebroeders, launched in 1830.

Fop Smit works on his own

| Name | Type | Laid Down | Launched | Tonnage | Principal | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vier Gebroeders[17] | Frigate | 23 Jun. 1830 | 643 ton | N/a | Captain F.C. Lupcke. | |

| Cornelis Werner Eduard [18] | Frigate | 7 Sep. 1839 | 400 last | Weiland, Van Walcheren, W. Ruys J.D. Zn. | Captain D.H. Kramer. | |

| Louise[19] | Ship | 25 Sep. 1840 | 500 last | J. Antheunis from Rotterdam. | Captain was J.F. Verschuur. | |

| Jan Daniël[20] | Barque | 27 May 1841 | 450 last | W. Ruys J.D. Zn. | ||

| Nieuw-Lekkerland[21] | Barque | 22 Jun. 1842 | 450 Java last | 's Gravenhaagsche Scheepsrederij, | Captain W.H, Kramer. | |

| Drie Gebroeders[22] | Barque | 30 Jul. 1844 | 300 last | W. Ruys J.D. Zn. | Captain T.C. Bauditz. | |

| Name | Type | Laid Down | Launched | Power | For | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prinses Marianne[23] | Steam yacht | In service Feb. 1833 | Rotterdam - Middelburg line | |||

| Koningin der Nederlanden[24] | Paddle steamer | Delivered 18 Apr. 1836 | Rotterdam - Nijmegen line[25] | |||

| Herzog von Nassau[26] | Paddle steamer | In service 7 Nov. 1837 | First ship of DGNM | 160 * 20', engines by Miller Ravenhill | ||

| Kronprinz(essin) von Preußen[27] | Paddle steamer | In service Sep.1838 | Rotterdam - Düsseldorf line of DGNM | |||

| Stad 's Hertogenbosch [28] | Paddle steamer | 1 Sep. 1838 | Rotterdam - 's-Hertogenbosch line | |||

| Stad Gorinchem[29] | Paddle steamer | In service Mar.? 1838 | 80 hp | Gorinchem - Middelburg line | Engines by Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel | |

| Kinderdijk[30] | Sea tug | 31 Aug. 1843 | 140 hp | Smit's tug service | Engines by Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel.[31] |

What made Fop Smit special was the amount of steam vessels he built. Most of these were for inland shipping lines. For ocean-going sailing ships Fop Smit started a close cooperation with Willem Ruys J.D. zn. (1809–1889) in the late 1830s. Fop built a long line of sailing ships for Willem Ruys, who managed them for multiple owners that formed a partenreederei for each ship. Fop Smit himself also became a partner in many of these ships. These ships formed the nucleus of what would later become the Royal Rotterdam Lloyd.

Smit Slikkerveer and J. & K. Smit

The ship Louise, launched in 1840 was launched from Fop Smit's shipyard in Slikkerveer, municipality Ridderkerk.[19] This also applied to Drie Gebroeders in 1844.[22] In 1851, the Fop Smit was launched by J. Smit from his shipyard in Slikkerveer.[32] From then on a list of ships was built in Slikkerveer by Jan Smit, a.k.a. as Jan Smit Fopszoon, or Jan Fz. Jan would also build several ships for his father, amongst these most of the Noach's, designed by his son Arie.[8]

In 1847 the sons of Jan Smit started their own shipyard J. & K. Smit on the terrain of their father Jan Foppe, southeast of that of Fop Smit. In 1906 J. & K. Smit had to leave this terrain.[33] It obviously moved to a terrain north of that of L. Smit, a situation recognizable on the black and white aerial photograph. In 1906 the new shipyard was getting readied.[34]

L. Smit towage service

In 1842 Fop Smit founded a towage service between Hellevoetsluis and Brouwershaven. At the time Hellevoetsluis was the outport of Rotterdam. Hellevoetsluis was connected to Rotterdam via the ship canal Canal through Voorne. Brouwershaven on Schouwen-Duiveland offered the best opportunity to wait for a favorable wind to sail through the English Channel. Another reason to found the tug service was to decrease the losses through accidents. Therefore, many shipping lines and insurers in Rotterdam united to enable the foundation of the towage service. Fop Smit would manage it and build its first tugboat of 140 hp. The company would receive a yearly subsidy by multiple commercial parties.[35] The first tug, Kinderdijk entered service in December 1843.[36]

This tug service would become a major customer of the shipyard. In April 1847 Fop Smit bought the steam yacht Stad Gorinchem for 45,000 guilders, to serve as the second ship of the tow service.[37] The tug service would be continued as L. Smit & Co., later Smit International.

The switch to iron (1846)

The first steam vessels were made of wood, but in time the first iron hulls appeared. In 1837 Fijenoord launched its first commercial iron steamship. In 1844 Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel secured orders for iron tugs on the Rhine, and started to construct its own shipyard. If iron was the future for inland navigation, Fop Smit had to follow suit, or loose this market. In June 1846 Fop Smit delivered the iron steam yacht Amicitia.[38] For construction in iron, the shipyard had to acquire a lot of technical skills. On the other hand, it could employ these on the market for sailing ships. In 1847 Fop Smit launched the schooner Industrie, the first iron sailing vessel of the Netherlands. Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel followed by launching its own iron schooners.

In 1853 Fop Smit launched California, the first Dutch iron ship.[39] (Ship in the sense of a fully rigged three mast sailing vessel.) Other innovations that Fop Smit promoted were iron masts[40] and iron stays. On 31 March 1856 the machine factory Diepeveen, Lels en Smit was founded. With Smit referring to Fop's son Leendert, and Fop's brother's son Jan.[41]

The main market for Dutch ocean going ships was the route to the Dutch East Indies. From about 1848 this profited from extremely favorable circumstances, such that even small old ships still made a profit. This lasted until freight rates suddenly plummeted in 1857. It led to a major crises in the Dutch shipping industry.[42] Fop Smit survived the crisis, and even built some more iron sailing ships in the early 1860s. These had the advantage that they suffered less partial damage to the cargo.[43] Another advantage of Smit's ships was their speed. E.g. in 1859 the clipper Noach made the trip from Batavia to Brouwershaven in a record time of 82 days.[44]

| Name | Type | Laid Down | Launched | Tonnage | Power | Principal | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japara[45] | Barque | 4 Nov. 1846 | 300 last | W. Ruys J.D. Zn. | |||

| Ida Elisabeth[46] | Barque | 15 Jul. 1847 | 300 last | W. Ruys J.D. Zn. | |||

| Industrie[47] | Iron schooner | 21 Sep. 1847 | 120 rye last | W. Ruys J.D. Zn. | First Dutch iron sailing vessel | ||

| Resident van Son[48] | Barque | 15 Jul. 1847[46] | 23 May 1849 | 450 last | W. Ruys J.D. Zn. | ||

| Doelwijk[49] | Barque | 23 May 1849[48] | 18 Sep. 1850 | 400 last | W. Ruys J.D. Zn. | Captain D.H. Kramer | |

| Fop Smit[32] | Barque | 18 Sep. 1850[49] | 2 Oct. 1851 | 350 last | |||

| Macassar[50] | Iron Screw steamship | 3 Jun. 1851 | Cores de Vries in D.E.I | ||||

| Ambon[51] | three mast screw ship | 3 Jun. 1851[50] | 26 Nov. 1851 | Cores de Vries in D.E.I | |||

| California[52] | Iron clipper | 1 Mar. 1852[53] | 24 Mar. 1853 | 400 last | Louis Bienfait en Zoon | First Dutch iron Ship | |

| Australie | Barque ship | 18 Dec. 1852[54] | 14 Mar. 1854[55] | 360 last | Q. Blauw in Amsterdam | ||

| De Maas[56] | Iron clipper | 25 Aug. 1854 | 400 last | C. Balguerie & Zonen, Rotterdam | |||

| Ternate[57] | Iron clipper | 25 Aug. 1854[56] | 16 Jul. 1855[57] | 400 last | H. van Rijckevorsel | 175 feet long[57] | |

| Noach[58] | Clipper | 19 Sep. 1857 | 500 last | Own account | First Dutch ship with all metal stays[59] | ||

| Oceaan[60] | Iron clipper | 24 Dec. 1856[60] | 17 Oct. 1857[61] | 500 last | Louis Bienfait en Zoon | ||

| Jan de Wit[62] | Iron clipper | 15 Jun. 1858 | 425 last | C. Balguerie en Zoon | |||

| Sara[63] | Iron screw steam ship | 18 Nov. 1861[64] | 5 May 1862 | 600 ton | Dordrecht - London line | ||

| Cornelia[65] | Iron barque | 29 May 1863 | 400 last | L. Bienfait en Zoon | |||

| Hoek van Holland[66] | Iron clipper | 2 Apr. 1864 | 500 last | Wm Ruys | |||

| Willem en Clara[67] | Iron screw steam vessel | 2 Apr. 1864[66] | 17 Sep. 1864 | Dordrecht - London line | Laid down as Stad Dordrecht[66] |

| Name | Type | Laid Down | Launched | Power | For | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amicitia[38] | Iron steam yacht | Delivered June 1846 | Rotterdam - Antwerp line | Engines by Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel | ||

| Jan van Arkel No.2[68] | Paddle steamer | 8 Mar. 1847 | 's-Hertogenbosch Gorinchem Schiedam line. | |||

| Amicitia No. 2[69] | Iron steam yacht | 16 Aug. 1847 | Rotterdam - Antwerp line | |||

| Zederik [70] | Iron Screw steam vessel | 19 Mar. 1852[71] | 12 Jul. 1852 | Gorinchem - Vianen line | ||

| Stad Middelburg[72] | Iron Steam yacht | 26 Mar. 1852[73] | 28 Dec. 1852 | Middelburg - Rotterdam line | ||

| Stad Rotterdam[74] | Steam yacht | 25 Jun. 1852[75] | 1 April 1853 | Rotterdam - 's-Hertogenbosch line | Engines by Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel | |

| Volharding[76] | Screw steam vessel | 8 Jun. 1853 | Leiden - Amsterdam line | |||

| Oude Maas[77] | Steam yacht | 8 Dec. 1853 | 60 hp[78] | Rotterdam - Dordrecht - Oud-Beijerland line | 120 * 16.5 feet[78] | |

| Stad Vlissingen[79] | Iron steam yacht | 30 Jan. 1854 | Vlissingen - Rotterdam line | |||

| De IJssel[80] | Iron steam vessel | 14 Dec. 1854 | Rotterdam - Gouda line | |||

| Brouwershaven.[81] | Iron tug | 19 Dec. 1854 | Smit's tug service | |||

| Telegraaf II[82] | Iron Steam yacht | 8 Mar. 1856 | Rotterdam - Antwerpen line | |||

| Telegraaf III[83] | Iron steam yacht | 17 Dec. 1857 | Rotterdam - Antwerpen line | |||

| Stad Gorinchem[84] | Iron screw steam vessel | 23 Nov. 1859[85] | 25 Apr. 1860 | Gorinchem - Amsterdam line | Engines by Diepeveen, Lels en Smit | |

| Reserve[86] | Iron tug | 8 Jun. 1860 | ||||

| Hellevoetsluis[87] | Iron tug | 3 Mar. 1862 | ||||

| Stad Amsterdam[88] | Screw steam vessel | 10 June 1863[89] | 2 Feb. 1864 | Gorinchem - Gouda - Amsterdam line | ||

| Karel Hertog van Gelder[90] | Screw steam vessel | 19 Feb. 1864[91] | 21 Jul. 1864 | Arnhem - Rotterdam - Schiedam line | ||

| Merwede[92] | Steam yacht | 17 Sep. 1864[67] | 23 Feb. 1865 | 90 hp | Gorinchem - Rotterdam line | Line owned by Fop Smit |

| De Linge[93] | Screw steam vessel | 29 Jul. 1865 | Gorinchem - Geldermalsen line | |||

| Leerdam[94] | Screw steam vessel | 29 Jul. 1865[93] | 28 Sep. 1865 | Gorinchem - Leerdam line | Engines by Diepeveen, Lels en Smit | |

| Merwede II[95] | Screw steam vessel | 1 Feb. 1866 | Rotterdam - Gorinchem line | Engines by Diepeveen, Lels en Smit |

History as L. Smit and Son shipyard

Succession of Fop Smit

After his death on 25 August 1866, Fop Smit was succeeded by his four sons. Leendert Smit would succeed to his shipyard, and his office as ambachtsheer of Nieuw Lekkerland. However, there can be little doubt that Fop Smit's estate consisted primarily of stock and participations in a lot of businesses. A substantial part was formed by the partial and or full ownership of many ships. These had probably not earned much, or even lost money since the 1857 shipping crisis. In summary, the financial power behind L. Smit en Zoon was a lot less than that behind Fop Smit shipyard. On 15 November Leendert made a partnership with his nephew Jan Smit V.[96] This probably brought a lot of capital back into the business.

In the night of 25 to 26 February 1869 most of the shipyard of L. Smit en Zoon would burn down.[97] The insurance would handle the damage to the satisfaction of the company.

L. Smit & Co. vs. L. Smit & Zoon

Fop Smit's tug service was continued by a consortium called L. Smit & Co. from Alblasserdam, which got its permit by decree of 4 January 1869.[98] In 1903 it became the N.V. L. Smit en Co.'s Sleepdienst. Thus L. Smit & Co, refers to the tug service. L. Smit en Zoon refers to the shipbuilding company.

Steam vessels for inland navigation

After the death of Fop Smit, the business of building ships for inland navigation kind of continued as usual. For deep rivers, the propeller became ever more popular, but for shallow waters, the paddle steamer remained in use. L. Smit was a leader in the construction of vessels for inland (passenger) shipping lines. This is shown by the number of vessels that L. Smit exported to Germany, and in particular by the fact that this export continued after German industrial capability had surpassed the Dutch in so many ways. A telltale sign is that some German shipping lines ordered vessels at L. Smit with Swiss engines.

| Name | Type | Laid Down | Launched | Power | For | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paddle steamer No. 1[99] | Paddle steamer | 24 Apr. 1866[100] | 21 Nov. 1866 | Later Köln-Düsseldorfer shipping line | 240 feet and 140 hp | |

| Paddle steamer No. 2[101] | Paddle steamer | 24 Apr. 1866[100] | 24 Nov. 1866 | Later Köln-Düsseldorfer shipping line | 240 * 25 * 3 feet and 140 hp[102] | |

| Zeeland[103] | Iron tug | 3 Aug. 1867 | L. Smit & Co. | |||

| Industrie[104] | Steam yacht | 2 May 1868 | ||||

| Industrie[105] | Screw steam vessel | 18 Jun. 1869 | Rudolf Wahl in Mannheim | Machines by Diepeveen, Lels & Smit. | ||

| Middelharnis?[106] | Paddle steamer | 22 Jul. 1869 | 24 Dec. 1869.[107] | Rotterdam - Middelharnis line. | Machines by Diepeveen, Lels & Smit. | |

| Deutscher Kaiser[108] | Iron paddle steamer | 30 May 1870 | 140 hp | Later Köln-Düsseldorfer line. | 260 feet, Engines by Ravenhill, Hodgson & Co. | |

| An[109] | Iron tug | 21 Sep. 1872 | 50 hp | Own account | ||

| A[110] | Steam Hopper barge | 10 Sep. 1877 | 25 hp | A. Volker Lz. Sliedrecht | ||

| Maasmond II[111] | Steam hopper barge | 30 Mar. 1878 | A. Volker Lz. & P.A. Bos | capacity 160 m3 | ||

| Leerdam[112] | Screw steam vessel | 22 Jan. 1879 | Rotterdam - Leerdam line | Machines by DLS | ||

| Argus[113] | Screw steam vessel | 17 Mar. 1879 | Rotterdam investigation service | DLS compound engines with surface condensers | ||

| A[114] | Paddle steamer | 11 Jun. 1879 | Rotterdam - Gorinchem line | Fop Smit & Co. | ||

| Vlaardingen III[115] | Screw steam vessel | c. Jul. 1880 | 25 hp | Vlaardingen steam vessel company | DLS compound engines | |

| Kolonel[116] | Screw steam vessel | 27 Sep. 1880 | Volker and Bos | |||

| Willem I[117] | Paddle steamer | 13 Apr. 1881 | Rederij Maas en Rijn | Engines DLS | ||

| A[117] | Paddle steamer | 13 Apr. 1881[117] | 28 Dec. 1881[118] | Preussisch-Rheinische | Engines Escher Wyss & Cie. | |

| Industrie III[119] | Screw steam vessel | 27 May 1881 | Rudolf Wahl Mannheim | |||

| Zealandia[119] | Sea screw tug | 27 May 1881 | 8 Nov. 1881[120] | For William Watkins London | ||

| Havik[121] | Screw tug | 17 Aug. 1881 | Tug service L. Smit & Co. | |||

| Colonia I[121] | Screw tug | 17 Aug. 1881[121] | 24 Dec. 1881[122] | Kölnische Dampf schleppschifffahrt | ||

| Valk II[123] | Screw Steam vessel | 4 Sep. 1882 | 25 hp comp. | Zeeuwsche Stoomboot Maatschappij | ||

| Queen[124] | Paddle steamer | 4 Sep. 1882[123] | 5 Jan. 1883 | Watkins, Weymouth Steamboat Company | ||

| Amsterdam[125] | Pump hopper barge | 4 Sep. 1882[123] | 19 Dec. 1882 | 45 hp comp.[123] | L. Kalis & Co. | Machines DLS 275 m3 capacity |

| Wodan[126] | Paddle steamer tug | 25 Jul. 1883 | L. Smit & Co. tug service | |||

| Colonia III[127] | Screw tug | 10 Aug. 1883 | 70 hp comp. | Kölnische Dampf schleppschifffahrt | Engines Escher Wyss & Cie. | |

| Industrie[128] | Screw steamer | 10 Aug. 1883[127] | 31 Oct. 1883 | 60 hp | Badische Schrauben-Dampfs. G. (BSDG) | Engines by Howaldt brothers |

| Hohenstaufen[129] | Steel paddle steamer | 10 Aug. 1883[127] | 26 Mar. 1884 | Preussisch-Rheinische | ||

| Oran[130] | Suction hopper barge | 18 Dec. 1884 | J. Dollfus, Oran | |||

| Industrie[131] | Steel twin screw ship | 18 Dec. 1884[130] | 22 Jan. 1885 | London - Cologne line (BSDG) | 200 * 28.5 * 12.5 feet 750 ton | |

| Industrie VI[132] | Screw Vessel | 19 Feb. 1885 | Oberrheinische Schifffahrts-Gesellschaft Mannheim | Engines by DLS | ||

| Industrie VII[133] | Screw Vessel | 30 Mar. 1885 | Oberrheinische Schifffahrts-Gesellschaft Mannheim | |||

| Oude Maas I[134] | Iron paddle steamer | 30 Mar. 1885 | 22 Jul. 1885 | comp. | Rotterdam - Oud-Beijerland line | Oude Maas Steamboat Company |

| Hansa[135][136][137] | Steel paddle steamer | 23 Oct. 1885 | 550 ihp | Rheinische Dampfschiffahrt G. Cologne | Engines Escher Wyss & Cie. | |

| Rhein[138] | Paddle Steamer | 29 Nov. 1887 | Preussisch-Rheinische D.G. | |||

| Koningin Emma[139] | Steel paddle steamer | 14 Jun. 1889 | Rotterdam - Mannheim line | Nederlandsche Stoombootrederij | ||

| Overstolz[140] | Paddle steamer | 2 Apr. 1890 | Preussisch-Rheinische D.G. | Engines Escher Wyss & Cie. | ||

| Wilhelmina[141] | Steel paddle steamer | 20 May 1891 | Rotterdam - Mannheim line | Ned. Stoombootrederij | ||

| Willem III[142] | Steel paddle steamer | 20 Aug. 1891 | 550 ihp | Rotterdam - Mannheim line | Ned. Stoombootreederij | |

| Oerona[143] | Paddle steamer | 17 Feb. 1893 | DLS, Bonn Beueler Faehr A.G. | |||

| A[144] | Steel paddle steamer | 18 Mar. 1893 | 10 Aug. 1893 | Preusische-Rheinische D.G. | Engines Escher Wyss & Cie. | |

| Hollandia[145] | Steel paddle steamer | 10 Aug. 1893[144] | 23 Nov. 1893 | 625 ihp | Rotterdam - Mannheim line | DLS Ned. Stoomboot Rederij |

| Concurrent I[146] | Steel tug | 22 Jan. 1895 | 500 ihp | Tug service Smit & Co. | 40 * 7.50 * 2.75 m | |

| W.F. Leemans[147] | Paddle steamer | 4 Jun. 1896 | 6 Oct. 1896 | 450 ihp | Rotterdam - Gorinchem line | Fop Smit & Co. |

| Steyn[148] | Paddle steamer | 2 Oct. 1902 | 400 hp | Rotterdam - Gorinchem line | Fop Smit & Co. | |

| Kruger[148] | Paddle steamer | 2 Oct. 1902 | 400 hp | Rotterdam - Gorinchem line | Fop Smit & Co. | |

| Leviathan[149] | Suction hopper barge | 10 Oct. 1904 | Galveston, Texas | American customer | ||

| Köln[150] | Suction dredger | 4 Jan. 1905 | Köln. Tiefbau Ges. | |||

| H.A.M. 2[151] | Suction hopper barge | 30 Jan. 1912 | Surabaya harbor works | Hollandsche Aannemings Maatschappij | ||

| Suriname[152] | Suction hopper barge | Kalis, Sliedrecht | 94 * 8.60 * 4.55 m |

Ocean going vessels

The opening of the Suez Canal in November 1869 radically changed shipping to the Dutch East Indies. In 1872 Stoomvaart Maatschappij Nederland established a reliable and fast shipping line between the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies. In about 1880 steamships still required a 25-50 guilders a last higher freight rate than sailing ships.[153] It meant that for higher value products, it became more economical to rely on steamships. For commodities like sugar and coffee, sail continued to be important.[154] It all led to an increase in the average size of sailing ships, from 454 ton in 1860 to about 1000 ton in 1880.[155]

The sailing ship with auxiliary power Nestor of 2,000 ton, was the last ship laid down by Fop Smit, and one of the first ships completed by L. Smit en zoon. The sailing ship with auxiliary power was supposed to sail most of the time, and to steam when the weather was unfavorable. The idea was probably sound, but the sailing ship with auxiliary power would lose to the ocean liner, which was supposed to use steam except for emergencies. The problem for L. Smit, and the rest of the Dutch shipbuilding industry, was that it was not capable of building machinery that was on par with that of British shipbuilders. When it finally could, it lacked the experience to prove its ability.[156]

The tables reflect this story. While L. Smit built dozens of river vessels in the 1870 and 1880s, only a handful of ocean-going vessels was built. The launch of Maetsuijcker in 1890 came about thanks to the foundationo of the Koninklijke Paketvaart-Maatschappij, which ordered four of her first ships at shipbuilding company De Schelde. De Schelde then subcontracted with L. Smit to build Maetsuijcker, for which she would herself build the engines.

| Name | Type | Laid down | Launched | Tonnage | Power | Principal | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nestor[157] | Iron clipper | 1 Sep. 1866 | 2000 ton | 50 hp | With aux. steam power | ||

| Industrie[158] | Iron clipper | 8 July 1868[159] | 24 April 1872. | 900 last | Own account | ||

| Adonis[160] | Iron screw steamer | February 1873 | Dunlop, Mees & Co. | For traffic in East Africa | |||

| Batavier[161] | Iron clipper | 22 April 1876 | 1,890 rt | Own account | |||

| Iberia[162] | Steel screw steamship | 4 June 1884 | W.H. Muller & Co. | ||||

| Maetsuijcker[163] | Screw ship | 5 Jul. 1890 | KPM in DEI | Engines by De Schelde | |||

| Tromp[164] | Steel frigate | 5 Jul. 1890[163] | 14 Feb. 1891 | Zur Muhlen | 2,600 ton | ||

| Noordzee[165] | Sea tug | Apr. 1891 | 17 Dec. 1891 | 600 ihp | Tug service L. Smit & Co | Engines De Schelde | |

| Oostzee | Sea tug | Apr. 1891 | 600 ihp | Tug service L. Smit & Co | Engines De Schelde | ||

| Tubalkaïn[166] | Steel frigate | 18 March 1893 | N/a | 2800 ton | Own account | ||

| Oceaan[167] | Steel ocean tug | 1 Dec. 1894 | 1,200 ihp | Tug service L. Smit & Co | Engines De Schelde | ||

| Tilburg[168] | Steamship | 10 Dec. 1917 | 1,378 Grt | 950 ihp | Transatlanta |

Further innovation

The shipyard continued to innovate. Construction of iron ships required specialized staff.[169] By 1882 engineer L.D. van Ouwerkerk from Delft University worked at L. Smit, and was also part of the executive board.[170] The requirements for skills also applied to the blue collar workers. In 1869 the shipyards of the Smit clan asked the municipality of Nieuw-Lekkerland to improve extended primary education by adding French, English, mathematics and construction drawing. They provided 1,075 guilders a year for an extra teacher to make this possible.[171]

The cooperation between the companies, which had earlier led to the establishment of machine factory Diepeveen, Lels & Smit, also led to the establishment of one of the first power stations of the Netherlands. By 1881 the shipyard had electric lighting, which enabled it to work more hours in winter.[119] The construction of Industrie, launched in January 1885 was another highlight. She was a steel twin screw ship which established a direct connection between London and Cologne. Meanwhile, shipbuilding in the Kinderdijk area was in a crisis by 1886.[172]

In July 1893 orders were given for the foundations of a new patent slip at Kinderdijk.[173] In 1899 the foundations for a boiler factory and machine factory were tendered.[174] In 1904 a new office was built.[175] In 1906 orders were given for a boiler shed, smithy and electricity station.

Ocean going tugs

Soon after its foundation, the shipbuilding company De Schelde started to cooperate with L. Smit. Arie Smit, younger brother of Jan Smit V, was the main founder of De Schelde. De Schelde would bring expertise about engines for the high seas into the Smit "cluster". It became the preferred supplier of L. Smit for the larger types of engines. In April 1891 it got orders for two triple expansion compound steam engines with surface condensers for two ocean going screw tugs that L. Smit was building for tug service L. Smit & Co.[176]

These two ocean going tugs were Noordzee and Oostzee. They were very much fit for service on the Nieuwe Waterweg, which had been completed in 1872. What made them special was their ability to serve on the ocean. For this they had a raised forecastle, a bridge, a covered stern, and bunkers large enough to store enough coal to steam for 12 days at full power. Their size of 39 * 7 * 4.25 (hold) m was another feature which enabled them to operate on the oceans.[177]

Oceaan (1894) came next. With a size of 45 * 8.60 * 4.60 m, and twice the power of the previous tugs, it clearly expressed the ambition of tug service L. Smit & Co. Indeed, the market for long distance towing would develop. It led to many orders for ocean going tugs at L. Smit and related shipbuilding companies. By March 1897 there were plans for two more Noordzee class tugs, and two more Oceaan class tugs.[178]

Dredging equipment

The specialization in dredging equipment like hopper barges can be traced back to at least 1877, and would prove to be a long-term success. For a time J. & K. Smit would build much more dredging equipment than L. Smit and Son did. After the 1900 Galveston hurricane the Americans ordered the steam suction hopper barge Leviathan at L. Smit. It showed that in niche areas, the Dutch shipbuilders could compete with the generally more advanced American shipbuilders.

Royal visit

On 5 March 1906 L. Smit and Son shipbuilding company was visited by Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands and Prince Hendrik. They were received by L.J. Smit (son of L. Smit), the company's engineer W. de Gelder, and L.F.J. van Vliet, mayor of Nieuw-Lekkerland. They also met Mrs. L.J. Smit and Jan Smit V. At the time, a bucket dredger for England was getting finished, as was the saloon paddle steamer Schiller. The suction hopper barge Seahound for a Sliedrecht company was launched by the queen. The tug Gouwzee of L. Smit & Co. was at the yard. The paddle steamer Emma was on the parallel slipway, where she was getting lengthened. The couple then visited the boiler factory, and the machine factory where saw many modern machines, most of them American.[179] In 1913 orders were given to add a new factory of 2,300 m3.[180]

World War I

World War I shut down the international market for river- coastal and dredging vessels, and forced the Dutch shipbuilding industry to construct sea-going ships.[181] It seems that in 1915, L. Smit still launched only dredging equipment.[182] However, that same year it already had three freighters at the slipways. The facilities at L. Smit made that these were small ships. Alblasserdam and Dagny I (ex-Kinderdijk), launched in 1916 were only 1,382 GRT. In 1917 L. Smit launched Kralingen and Tilburg of 1,378 Grt / 2,200 ton dwt.[183] In 1918 she had two more of these ships (No. 795 and 796) on the slipway.[184] These remained on the slipway in 1918.

N.V. L. Smit & Zoon's Scheeps- en Werktuigbouw (1920–1965)

| Name | Type | Laid Down | Launched | Size | Power | Principal | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zwarte Zee[185] | Ocean going tug | 2 Jun. 1933 | 63.40 * 10.13 * 5.90 m | 4,000 ihp | L. Smit & Co. | Diesel eng. | |

| Adolphe Delands[186] | Suction hopper barge | 12 Jun. 1937 | 49 * 8.60 * 4.55 m | 350 hp | Port of Safi | ||

| Le Puissant[187] | Sea going tug | 1 Mar. 1938 | 33 * 7.80 * 4 m | 800 hp | Dunkirk | Werkspoor eng. | |

| Rode Zee[188] | Ocean going tug | 25 Apr. 1938 | 45 * 8.10 * 4.85 m | 1,300 hp | L. Smit & Co. | Smit-M.A.N. eng. |

Incorporated

L. Smit en Zoon was incorporated in March 1920 as N.V. L. Smit & Zoon's Scheeps- en Werktuigbouw.[189]

Interwar period

After the war there was a boom in shipbuilding. Already in 1922, more than enough ships had been built, and shipping lines started to lose money. Shipbuilders then cut hours and wages, which L. Smit also did. In 1922 L. Smit launched a suction hopper barge and a bucket dredger for its own account. It ended the year with a freighter, a suction hopper barge, a suction dredger and a bucket dredger at the slipways, all for its own account. This was a rather unusual order portfolio in comparison to other shipyards. E.g. J. & K. Smit had regular orders for 5 ships.[190] The January 1923 Occupation of the Ruhr was very damaging to the Dutch shipbuilding industry, especially in South Holland. Raw material prices soared, and demand for ships collapsed.

In 1925 the situation was somewhat better with the construction of the suction hopper barges Meuse and H.A.M. 301, two Dortmund Ems Canal ships and some barges for the Thames.[191] In 1926 4 vessels were launched.[192] In 1927 two tugs and some barges were built. For L. Smit & Co. the sea going tug Noordzee was built.[193] In 1928 L. Smit launched two bucket dredgers and some barges.[194] In 1929 L. Smit launched three suction hopper barges, a bucket dredger, and a few smaller vessels.[195]

For the Dutch shipbuilding industry, the third quarter of 1929 would be the busiest since the fourth quarter of 1922.[196]

By mid 1930, the Great Depression took its toll. In 1930 L. Smit still launched three tugs and two dredging barges. It next took the risk to build a bucket dredger and a suction hopper barge without having a customer for them.[197] In 1932 only two dredging barges for Belgium, and the bucket dredger G.G.A, were launched. By the end of that year it had the tug Zwarte Zee, and two dredging vessels under construction.[198] Zwarte Zee was the only ship launched by L. Smit in 1933. By the end of that year it had the small tanker Leonidas 3 under construction. In 1934 it launched the small motor tanker Leonidas III and two dredging vessels. By the end of that year it had two small motor tankers and one cutter suction dredger on order.[199] By the end of 1935 only about a hundred people were still employed by L. Smit.[200]

In 1936 the shipbuilding market started to recover.[201] L. Smit now built a number of heavy tugboats, some more coastal motor tankers, and also more dredging equipment.

World War II

The shipbuilding company continued to operate during World War II. In 1941 the tug Javazee was launched, but she capsized immediately after.[202]

IHC Holland

Cooperation in IHC Holland

The Industriële Handels Combinatie IHC in the Hague was a partnership founded during the war. The idea was focused on the dredging market, where the partners deemed themselves too small to take on the expected post-war orders on their own.[203] The partnership consisted of Conrad Shipyard in Haarlem, Gusto Shipyard in Schiedam, Machine Factory De Klop in Sliedrecht, J. & K. Smit in Kinderdijk, L. Smit in Kinderdijk, and Verschure & Co's in Amsterdam. These were all strong players in dredging, but wanted to be more efficient and limit risk. In sales e.g. it was very inefficient for all these relatively small companies to have their own agents abroad.[204]

In December 1946 IHC contracted with Turkey for 6 twin screw passenger ships.[205] In September 1947 IHC got a French order for five big dredgers. The orders were then divided over the partners. In 1951 L. Smit launched a hopper barge for the harbor of Calcutta. On 18 June 1953 L. Smit launched Edgar Bonnet, the strongest tug of the world, for the Suez Canal Company.[206] In 1958 L. Smit received orders for two more tugs of the same size as Edgar Bonnet, but with Diesel-electric propulsion.

Meanwhile, the partners continued to contract as separate legal entities on the national market. On 23 September 1947 L. Smit en Zoon's launched the ocean going tug Humber for L. Smit & Co. On 16 July 1955 HAM 302 was launched for Hollandse Aannemings Maatschappij. This was a trailing suction dredger hopper of 72 m length. HAM 304 (later W.D. Mersey), launched in March 1960, measured 94.50 * 16 * 7.30 m, could carry 4.000 ton and had 3,625 hp.[207]

Merger into IHC Holland

In 1965 the boards of 5 of the 6 companies which cooperated in IHC Holland decided to merge their companies. Conrad Shipyard en Stork Hijsch N.V. could not join, because it was part of the Stork conglomerate.[208] In 1966 IHC Holland started to merge L. Smit and J. &. K. Smit shipyards into a partnership known as Smit Kinderdijk v.o.f. In 1978 IHC Holland was split in three parts, with the holding getting renamed to Caland Holdings in 1979.[209] The offshore part became known as IHC Inter. In 1984 these merged again into IHC Caland.

The modern shipyard still contains some old buildings. See the large buildings on the interwar aerial photograph marked with 'J. & K. Smit' and 'L. Smit & Zn'. These are now (2021) completely hemmed in by more modern buildings. The slipways and most of the harbors are now covered with halls in order to work more comfortable and effectively.

Notes

- ^ a b c Vorsterman van Oyen 1885, p. 178.

- ^ Vorsterman van Oyen 1885, p. 184.

- ^ a b Boersma 1939, p. 402.

- ^ Molhuysen, Blok & Knappert 1921, p. column 761.

- ^ Molhuysen, Blok & Knappert 1921, p. column 758.

- ^ Vorsterman van Oyen 1885, p. 181.

- ^ "Huwelijken, Geboorten en Sterfgevallen". Het vaderland. 13 December 1893.

- ^ a b c Van Sandick 1925, p. 340.

- ^ a b c Boersma 1939, p. 403.

- ^ "Rotterdam den 31 October". Rotterdamsche courant. 1 November 1825.

- ^ "Rotterdam, den 10 Mei". Nederlandsche staatscourant. 13 May 1825.

- ^ "Rotterdam den 16 Maart". Opregte Haarlemsche Courant. 21 March 1826.

- ^ "Rotterdam, den 15 November". Nederlandsche staatscourant. 17 November 1826.

- ^ "Rotterdam, den 26 mei". Rotterdamsche courant. 27 May 1828.

- ^ "Rotterdam den 26 Mei". Rotterdamsche courant. 27 May 1828.

- ^ "Rotterdam den 29 december". Rotterdamsche courant. 30 December 1828.

- ^ "Rotterdam den 25 junij". Rotterdamsche courant. 26 June 1830.

- ^ "Rotterdam, 9 Sept". Algemeen Handelsblad. 11 September 1839.

- ^ a b "Rotterdam den 25 september". Rotterdamsche courant. 26 September 1840.

- ^ "Rotterdam den 28 mei". Rotterdamsche courant. 29 May 1841.

- ^ "La Haye, le 24 juin". Journal de La Haye (in French). 25 June 1842.

- ^ a b "Binnenlandsche Berigten". Nederlandsche staatscourant. 3 August 1844.

- ^ "Middelburg den 4 maart". Middelburgsche courant. 5 March 1833.

- ^ "Nijmegen den 21. Junij". Utrechtsche courant. 24 June 1836.

- ^ "Binnenlandsche Berichten". Algemeen Handelsblad. 22 April 1836.

- ^ "Duitsche Post". Algemeen Handelsblad. 11 November 1837.

- ^ "Nederlanden". Algemeen Handelsblad. 10 September 1838.

- ^ "Nederlanden". Dagblad van 's Gravenhage. 5 October 1838.

- ^ "Gorinchem, 23 Februarij 1841". Opregte Haarlemsche Courant. 27 February 1841.

- ^ "La Haye, 2 septembre". Journal de La Haye (in French). 3 September 1843.

- ^ "La Haye, 2 janvier". Journal de La Haye (in French). 3 January 1843.

- ^ a b "Rotterdam den 3 october". Rotterdamsche courant. 4 October 1851.

- ^ "Een historische plek op scheepsbouwgebied". Scheepvaart. 28 September 1906.

- ^ "Binnenland". Rotterdamsch nieuwsblad. 14 February 1906.

- ^ "Rotterdam den 23 december". Rotterdamsche courant. 24 December 1842.

- ^ "Rotterdam den 22 december". Rotterdamsche courant. 23 December 1843.

- ^ "Rotterdam, 20 April". N.R.C. 21 April 1847.

- ^ a b "Binnenland". N.R.C. 19 June 1846.

- ^ "Het ijzeren clipper schip California". Rotterdamsche courant. 8 February 1854.

- ^ "Nieuwstijdingen betrekkelijk Nijverheid". Nijverheids-courant. 8 May 1852.

- ^ "Geregtelijke Aankondigingen". Nederlandsche staatscourant. 16 April 1856.

- ^ Gaastra 2004, p. 8.

- ^ Zeverijn 1881, p. 34.

- ^ "Rotterdam, 13 Februarij". N.R.C. 14 February 1859.

- ^ "Rotterdam, 4 Nov". Algemeen Handelsblad. 6 November 1846.

- ^ a b "Rotterdam den 16 Julij". Rotterdamsche courant. 17 July 1847.

- ^ "Rotterdam den 22 september". Rotterdamsche courant. 23 September 1847.

- ^ a b "Rotterdam, 23 Mei". Algemeen Handelsblad. 25 May 1849.

- ^ a b "Rotterdam, 18 September". N.R.C. 19 September 1850.

- ^ a b "Rotterdam, 3 Junij". N.R.C. 4 June 1851.

- ^ "Binnenland". Algemeen Handelsblad. 28 November 1851.

- ^ "Nederlanden". Dagblad van Zuidholland en 's Gravenhage. 28 March 1853.

- ^ "Alblasserdam, 1 maart". Algemeen Handelsblad. 4 March 1852.

- ^ "Amsterdam, Zondag 19 December". Algemeen Handelsblad. 20 December 1852.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 14 Maart". Algemeen Handelsblad. 16 March 1854.

- ^ a b "Nieuw Lekkerland, 25 Aug". Hoornsche courant. 2 September 1854.

- ^ a b c "Rotterdam den 17 julij". Rotterdamsche courant. 18 July 1855.

- ^ "Amsterdam, Dingsdag 22 September". Algemeen Handelsblad. 23 September 1857.

- ^ "Binnenland". N.R.C. 2 May 1858.

- ^ a b "Kinderdijk, 24 December". N.R.C. 25 December 1856.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 17 October". N.R.C. 18 October 1857.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 16 Junij". Algemeen Handelsblad. 18 June 1858.

- ^ "Dordrecht 5 mei". Rotterdamsche courant. 7 May 1862.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 18 November". N.R.C. 19 November 1861.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 29 Mei". N.R.C. 31 May 1863.

- ^ a b c "Kinderdijk, 2 April". Algemeen Handelsblad. 4 April 1864.

- ^ a b "Rotterdam, 17 September". N.R.C. 18 September 1864.

- ^ "Binnenland". Algemeen Handelsblad. 11 March 1847.

- ^ "Binnenland". N.R.C. 31 May 1848.

- ^ "Berigten". N.R.C. 15 July 1852.

- ^ "Gorinchem, 19 Maart". Algemeen Handelsblad. 22 March 1852.

- ^ "NieuwLekkerland, 28 Dec". Algemeen Handelsblad. 31 December 1852.

- ^ "NieuwLekkerland, 26 Maart". Algemeen Handelsblad. 29 March 1852.

- ^ "Rotterdam den 4 april". Rotterdamsche courant. 5 April 1853.

- ^ "Nieuw-Lekkerland, 25 Junij". Algemeen Handelsblad. 28 June 1852.

- ^ "Rotterdam, den 13 Junij". Rotterdamsche courant. 14 June 1852.

- ^ "Binnenland". De Grondwet. 13 December 1853.

- ^ a b "Rotterdam den 22 junij". Rotterdamsche courant. 23 June 1843.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 30 Jan". Algemeen Handelsblad. 1 February 1854.

- ^ "Rotterdam den 14 december". Rotterdamsche courant. 15 December 1854.

- ^ "Rotterdam den 21 december". Rotterdamsche courant. 22 December 1854.

- ^ "Rotterdam, 8 Maart". Algemeen Handelsblad. 12 March 1856.

- ^ "Staten-Generaal". Rotterdamsche courant. 19 December 1857.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 25 April". Nieuw Amsterdamsch handels- en effectenblad. 27 April 1860.

- ^ "Gorinchem, 23 Nov". Algemeen Handelsblad. 25 November 1859.

- ^ "Kinderdijk 9 junij". Rotterdamsche courant. 11 June 1860.

- ^ "Kinderdijk 3 maart". Rotterdamsche courant. 4 March 1862.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 2 Februarij". N.R.C. 4 April 1864.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 10 Junij". Algemeen Handelsblad. 12 June 1863.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 21 Julij". Algemeen Handelsblad. 23 July 1864.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 19 Februarij". N.R.C. 20 February 1864.

- ^ "Kinderdijk 23 februarij". Rotterdamsche courant. 25 February 1865.

- ^ a b "Kinderdijk, 29 Julij". N.R.C. 30 July 1865.

- ^ "Kinderdijk 28 september". Rotterdamsche courant. 30 September 1865.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 1 Februarij". N.R.C. 3 February 1866.

- ^ "Bekendmaking". N.R.C. 18 November 1866.

- ^ "Gemengde Berigten". N.R.C. 27 February 1869.

- ^ "Ministerie van Binnenlandsche Zaken". Nederlandsche staatscourant. 10 January 1869.

- ^ "Kinderdijk 21 november". Rotterdamsche courant. 22 November 1866.

- ^ a b "Kinderdijk, 24 April". N.R.C. 26 April 1866.

- ^ "Kinderdijk 24 november". Rotterdamsche courant. 27 November 1866.

- ^ "Binnenlandsche Berigten". Delftsche courant. 22 January 1867.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 3 Aug". Algemeen Handelsblad. 5 August 1867.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 2 Mei". N.R.C. 3 May 1868.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 18 Juni". Het vaderland. 21 June 1869.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 22 Juli". N.R.C. 23 July 1869.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 24 December". N.R.C. 25 December 1869.

- ^ "Nieuwsberichten". Vlaardingsche courant. 1 June 1870.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 21 September". Vlaardingsche courant. 1 June 1870.

- ^ "'s Gravenhage 11 September". Het Vaderland. 12 September 1877.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 30 Maart". Algemeen Handelsblad. 1 April 1878.

- ^ "Binnenland". Rotterdamsch nieuwsblad. 24 January 1879.

- ^ "Laatste Nieuwstijdingen". Rotterdamsch nieuwsblad. 17 March 1879.

- ^ "Binnenland". Rotterdamsch nieuwsblad. 13 June 1879.

- ^ "Binnenlandsche Berigten". Nieuwsblad, gewijd aan de belangen van de Hoeksche Waard. 21 August 1880.

- ^ "Binnenland". Het Vaderland. 28 September 1880.

- ^ a b c "Binnenland". Het Vaderland. 15 April 1881.

- ^ "Binnenland". Het Vaderland. 30 December 1881.

- ^ a b c "Binnenland". Het Vaderland. 28 May 1881.

- ^ "Binnenland". Het Vaderland. 9 November 1881.

- ^ a b c "Kinderdijk, 17 Aug". Dagblad van Zuidholland. 20 August 1881.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 24 Dec". Dagblad van Zuidholland. 29 December 1881.

- ^ a b c d "Kinderdijk, 24 Dec". Het vaderland. 5 September 1882.

- ^ "Binnenland". Het vaderland. 6 January 1883.

- ^ "Binnenland". Het vaderland. 20 December 1882.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 26 Juli". De Standaard. 30 July 1883.

- ^ a b c "Kinderdijk, 10 Aug". Algemeen Handelsblad. 11 August 1883.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 31 Oct". Algemeen Handelsblad. 2 November 1883.

- ^ "Binnenland". Het Vaderland. 28 March 1884.

- ^ a b "Binnenland". Het Vaderland. 20 December 1884.

- ^ "Binnenlandsch Nieuws". Dagblad van Zuidholland. 24 January 1885.

- ^ "Binnenland". Het Vaderland. 21 February 1885.

- ^ "Binnenland". Het Vaderland. 31 March 1885.

- ^ "Binnenland". Rotterdamsch nieuwsblad. 23 July 1885.

- ^ "Binnenland". Het vaderland. 24 October 1885.

- ^ "Kölner Local-Nachrichten". Kölnische Zeitung. 12 February 1886.

- ^ "Vermischte Nachrichten". Kölnische Zeitung. 4 April 1886.

- ^ "Binnenland". Het vaderland. 30 November 1887.

- ^ "Binnenland". Het vaderland. 15 June 1889.

- ^ "Binnenlandsch Nieuws". Het nieuws van den dag. 7 April 1890.

- ^ "Te water gelaten". Algemeen Handelsblad. 21 May 1891.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 20 Aug". Dagblad van Zuidholland. 22 August 1891.

- ^ "Te water gelaten". Algemeen Handelsblad. 22 August 1891.

- ^ a b "Kinderdijk, 10 Aug". Dagblad van Zuidholland. 12 August 1893.

- ^ "Binnenland". Nieuwe Vlaardingsche courant. 25 November 1893.

- ^ "Te water gelaten schepen". Scheepvaart. 23 January 1895.

- ^ "Een nieuwe boot der firma Fop Smit & Co. water gelaten schepen". Het Vaderland. 12 March 1897.

- ^ a b "Stadsnieuws". Rotterdamsch nieuwsblad. 3 October 1902.

- ^ "Nijverheid". De nieuwe courant. 10 October 1904.

- ^ "Te water gelaten". Algemeen Handelsblad. 6 January 1905.

- ^ "Krimpen a.d. Lek". Rotterdamsch nieuwsblad. 30 January 1912.

- ^ "Binnenland". Scheepvaart. 18 November 1915.

- ^ Zeverijn 1881, p. 28.

- ^ Zeverijn 1881, p. 31.

- ^ Zeverijn 1881, p. 19.

- ^ Lintsen 1993, p. 96.

- ^ "Binnenland". Dagblad van Zuidholland. 4 September 1866.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 24 April". Het Vaderland. 27 April 1872.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 8 Julij". Algemeen Handelsblad. 10 July 1866.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 20 Feb". Dagblad van Zuidholland. 22 February 1873.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 22 April". Opregte Haarlemsche Courant. 26 April 1876.

- ^ "Scheepstijdingen". Rotterdamsch nieuwsblad. 7 June 1884.

- ^ a b "Kinderdijk, 5 Juli". Dagblad van Zuidholland. 8 July 1890.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 14 Februari". Dagblad van Zuidholland. 17 February 1891.

- ^ "Alblasserdam,17 December". Dagblad van Zuidholland. 22 August 1891.

- ^ "Kinderdijk, 18 Maart". Dagblad van Zuidholland. 22 August 1891.

- ^ "Te water gelaten schepen". Scheepvaart. 2 December 1894.

- ^ "Landbouw en Nijverheid". De Nederlander. 14 December 1917.

- ^ Zeverijn 1881, p. 46.

- ^ "Koninklijk Instituut van Ingnieurs". Dagblad van Zuidholland. 13 September 1882.

- ^ "Residentienieuws". Het vaderland. 7 May 1869.

- ^ "Binnenland". De Maasbode. 9 September 1886.

- ^ "Binnenlandsch Nieuws". Het nieuws van den dag. 1 July 1893.

- ^ "Binnenland". Rotterdamsch nieuwsblad. 4 April 1899.

- ^ "Binnenland". Rotterdamsch nieuwsblad. 14 March 1904.

- ^ "Vlissingen, 14 April". Algemeen Handelsblad. 16 April 1891.

- ^ "Nieuwsberichten". Nieuwe Vlaardingsche courant. 15 April 1891.

- ^ "Scheepstijdingen". Harlinger courant. 24 March 1897.

- ^ "Het Koninklijk bezoek aan Rotterdam". Land en Volk. 5 March 1906.

- ^ "Binnenlandsch Nieuws". Het nieuws van den dag. 21 June 1913.

- ^ "Scheepsbouw". Scheepvaart. 20 February 1916.

- ^ "Te water gelaten schepen in 1915". Scheepvaart. 31 December 1915.

- ^ "Te water gelaten schepen in 1917". Scheepvaart. 31 December 1917.

- ^ "schepen in aanbouw op 31 December 1918". Scheepvaart. 4 January 1919.

- ^ "De motorsleepboot Zwarte Zee te water gelaten". Rotterdamsch nieuwsblad. 2 June 1933.

- ^ "Proefvaart". De Nederlander. 7 September 1937.

- ^ "Slbt. le Puissant te waterg gelaten". De Maasbode. 2 March 1938.

- ^ "Tewaterlating Sleepboot Roode Zee". Scheepvaart. 26 April 1938.

- ^ "Medeelingen van verschillenden Aard". Nederlandsche Staatscourant. 31 March 1920.

- ^ "schepen in aanbouw op 31 December 1922". Scheepvaart. 5 January 1923.

- ^ "Te water gelaten schepen in 1925". Scheepvaart. 31 December 1925.

- ^ "Te water gelaten schepen in 1926". Scheepvaart. 31 December 1926.

- ^ "Te water gelaten schepen in 1927". Scheepvaart. 11 January 1928.

- ^ "Te water gelaten schepen in 1928". Scheepvaart. 17 January 1929.

- ^ "Te water gelaten schepen". Scheepvaart. 23 January 1930.

- ^ "Nederlandsche Scheepsbouw en Buitenlandsche mededinging". Algemeen Handelsblad. 12 January 1930.

- ^ "Te water gelaten schepen in 1930". Scheepvaart. 15 January 1931.

- ^ "Te water gelaten schepen in 1932". Scheepvaart. 17 January 1933.

- ^ "Te water gelaten schepen in 1934". Scheepvaart. 22 January 1935.

- ^ "Nieuw Lekkerland en haar nijverheidscentrum Kinderdijk". De standaard. 30 December 1935.

- ^ "Lloyd's overzicht van de wereldscheepsbouw in 1936". De Locomotief. 15 February 1937.

- ^ "Javazee bij tewaterlating gekapseisd". Algemeen Handelsblad. 15 February 1937.

- ^ "De "Grote Zes" verdelen de wereld". Algemeen Dagblad. 20 November 1958.

- ^ "Samenwerking voor export". Trouw. 12 April 1947.

- ^ "Turkse order voor Nederland". Het vrije volk. 28 December 1946.

- ^ "Sterkste sleper ter wereld te water gelaten". Het Parool. 18 June 1953.

- ^ "Sleephopperzuiger HAM 304 (with picture)". Gereformeerd gezinsblad. 31 March 1960.

- ^ "Vijf werven fuseren". Het Parool. 15 July 1965.

- ^ "Buitenlandse belegger ruim 20 pct. in Caland". De Telegraaf. 7 June 1984.

References

- Boersma, P. (1939), Alblasserdam's heden en verleden, J. Noorduyn en Zoon, Gorinchem

- Gaastra, F.S. (2004), Vragen over de koopvaardij. De 'Enquête omtrent den toestand van de Nederlandsche koopvaardijvloot' uit 1874 en de achteruitgang van de handelsvloot, Leiden University, hdl:1887/4519

- Lintsen, H.W. (1993), Geschiedenis van de techniek in Nederland. De wording van een moderne samenleving 1800-1890. Deel IV

- Molhuysen, P.C.; Blok, P.J.; Knappert, L. (1921), "Smit", Nieuw Nederlandsch Biografisch Woordenboek (NNBW), A.W. Sijthoff's, Leiden

- Van Sandick, R.A. (1925), "Arie Smit", De Ingenieur (17), Kon. Instituut van Ingenieurs, Ver. van Delftsche Ingenieurs: 339–342

- Vorsterman van Oyen, A.A. (1885), "Geslachtslijst der Familie Smit", Algemeen Nederlandsch Familieblad, Genealogisch en Herladische Archief, 's-Gravenhage, pp. 177–184

- Zeverijn, S.B. (1881), Onze Oost-Indië Vaarders, J.F.V. Behrens, Amsterdam