Konstantin Hierl

Konstantin Hierl | |

|---|---|

Hierl in 1941 | |

| Reichsarbeitsführer Reich Labour Service | |

| In office 26 June 1935 – 8 May 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Reichsleiter | |

| In office 10 September 1936 – 8 May 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Reichsminister without Portfolio | |

| In office 24 August 1943 – 30 April 1945 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 24 February 1875 Parsberg, Bavaria, German Empire |

| Died | 23 September 1955 (aged 80) Heidelberg, West Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Political party | Nazi Party |

| Occupation | Military officer |

| Civilian awards | German Order Golden Party Badge |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Royal Bavarian Army Reichswehr |

| Years of service | 1893–1924 |

| Rank | Oberst Generalmajor (Honor rank) |

| Unit | I Royal Bavarian Reserve Corps |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

| Military awards | Iron Cross, 1st and 2nd class War Merit Cross, 1st and 2nd class with swords |

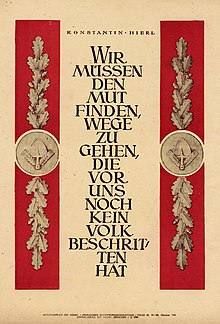

Konstantin Hierl (24 February 1875 – 23 September 1955) was a German career military officer who became a major figure in the administration of Nazi Germany. An associate of Adolf Hitler before he came to national power, Hierl became the head of the Reich Labour Service and a Reichsleiter of the Nazi Party. Following the end of the Second World War, he was tried, found guilty of major offenses and sentenced to five years in a labour camp.

Early life

Hierl was born in Parsberg near Neumarkt in the Bavarian Upper Palatinate region, and attended secondary school (Gymnasium) in Burghausen and Regensburg. In 1893 he joined the Bavarian Army as a cadet.[1] He was commissioned as a Leutnant in 1895 and graduated from the military academy in 1902. He was promoted to Hauptmann in 1909 and served as a company commander in the Bavarian infantry. During World War I, Hierl served as a member of the general staff of the I Royal Bavarian Reserve Corps, part of the German 6th Army fighting on the western front. He attained the rank of Oberstleutnant and was awarded the Iron Cross, 1st and 2nd class, the Bavarian Military Merit Order, 3rd class with swords and other decorations.

Upon the German defeat and the November Revolution of 1918, Hierl became head of a paramilitary Freikorps unit and fought in Augsburg against supporters of the Spartacist uprising.[2] He remained in the Reichswehr, the military of the Weimar Republic, and served in the Ministry of the Reichswehr where he played a role in organizing the Black Reichswehr paramilitary forces in the early years of the republic. He was discharged from the service with the rank of Oberst in September 1924, in part due to his support of General Erich Ludendorff's participation in the Beer Hall Putsch. He began to be involved in politics as an organizer in southern Germany for Ludendorff's far-right Tannenbergbund political society between 1925 and 1927.[3][4]

Nazi Party career

In April 1929, Hierl joined the Nazi Party (membership number 126,752) and became head of Organization Department II that same year, serving as deputy to Gregor Strasser.[1] As an early Party member, or Alter Kämpfer, he would later be awarded the Golden Party Badge. In the federal election of 1930, he was elected to the Reichstag from the party list. He continued to be reelected throughout the Nazi regime, switching to represent electoral constituency 6 (Pomerania) from November 1933.[5] On 5 June 1931, two years before the Nazi Party ascended to national power, Hierl became head of the Freiwilliger Arbeitsdienst or FAD (Voluntary Labour Service), a state sponsored voluntary labour organization that provided manpower for civic and agricultural construction projects. There were many such organizations in Europe at the time, founded to provide much-needed employment during the Great Depression. On 18 December 1931, together with Strasser, he was granted the rank of SA-Gruppenführer in the Nazi paramilitary unit, the Sturmabteilung.[6][7]

Hierl was already a high-ranking member of the Party when it took power in January 1933. He remained the head of the labour organization – now called the Nationalsozialistischer Arbeitsdienst, or NSAD (National Socialist Labor Service). Adolf Hitler named him as State Secretary in the Reich Ministry of Labour under Franz Seldte, with the order to build up a powerful labour service organization.[1] Facing Seldte's resistance, Hierl in 1934 switched to the Reich Ministry of the Interior under Wilhelm Frick in the rank of a Reichskommissar. Hierl was also named a member of Hans Frank's Academy for German Law.[8] On 11 July 1934, the NSAD was renamed Reichsarbeitsdienst or RAD (Reich Labor Service), which Hierl would control as its chief until the end of World War II. The Reich Labor Service was divided into two major sections, one for men (Reichsarbeitsdienst Männer - RAD/M) and one for women (Reichsarbeitdienst der weiblichen Jugend - RAD/wJ). The RAD was composed of 40 Gau-sections (Arbeitsgau). In 1936 the Reich Labor Service built the model village of Hierlshagen (present-day Ostaszów in Poland), named after Hierl.

Hierl was named Reich Labor Leader (Reichsarbeitsführer) on 26 June 1935 and Reichsleiter, the second highest political rank in the Nazi Party, on 10 September 1936.[1][9] He also was granted the honor rank of Generalmajor in the Wehrmacht.[8] In August 1943, when Heinrich Himmler replaced Frick as Interior Minister, Hierl also left the ministry and reported directly to Hitler as the head of a Supreme Reich Authority (Oberste Reichsbehörde). He also was named a Reichsminister without portfolio in Hitler's cabinet.[10][11]

During the war, hundreds of RAD units were engaged in supplying frontline troops with food, ammunition, repairing damaged roads and constructing and repairing airstrips. RAD units constructed coastal fortifications (many RAD men worked on the Atlantic Wall), laid minefields, manned fortifications, and even helped guard vital locations and POW camps. The role of the Reich Labor Service was not limited to combat support functions. Hundreds of RAD units received training as anti-aircraft specialists and were deployed to flak batteries.[12]

On 24 February 1945, Hierl was awarded the German Order, the highest decoration the Nazi Party could bestow on an individual.[13] After the war, he was arrested and interned in the Ludwigsburg internment camp. He was tried before a denazification tribunal and, on 21 August 1948, was found guilty as a "major offender". He received a sentence of three years in a labour camp but was immediately freed on the basis of time served.[14] On appeal, his conviction was upheld by the North Württemburg Central Appeals Chamber on 22 December 1949. However, the sentence was revised to five years in a labour camp and the forfeiture of half of his income above 250 DM per month.[15] Following his release from custody, he lived in Heidelberg where he worked as a Völkisch publicist and propagandist. He also published his memoirs titled: Im Dienst für Deutschland 1918-1945 (In Service for Germany, 1918-1945). He died in September 1955.[16]

Decorations

- German Order with Oak Leaves and Swords: 24 February 1945

- Prussian House Order of Hohenzollern, Knight's Cross (WWI)

- Prussian Iron Cross 1st and 2nd Class (WWI)

- Bavarian Military Merit Order, 3rd Class with Swords (WWI)

- Bavarian Prince Regent Luitpold Medal (pre-WWI)

- Bavarian Service Cross (pre-WWI)

- Austrian-Hungarian Military Merit Cross, 3rd Class with War Decoration (WWI)

- The Honour Cross of the World War 1914/1918 (pre-WWII)

- War Merit Cross 1st and 2nd Class with Swords (WWII)

- Golden Party Badge (pre-WWII)

References

- ^ a b c d Hamilton 1984, p. 227.

- ^ Konstantin Hierl short biography in the Reichstag Members Database

- ^ Konstantin Hierl in Deutsche Biographie

- ^ Konstantin Hierl Biography in the Files of the Reich Chancellery

- ^ Konstantin Hierl entry in the Reichstag Members Database

- ^ Führerbefehl Nr. 6, 18 December 1931

- ^ Campbell 1998, p. 216, n.125.

- ^ a b Klee 2007, p. 254.

- ^ Studt 2002, p. 64.

- ^ "Gestapo Rule In Germany. Himmler's New Post". The Times (London). No. 49633. 25 August 1943. p. 4.

- ^ Zentner & Bedürftig 1997, p. 774.

- ^ McNab 2009, p. 55.

- ^ Angolia 1989, pp. 223–224.

- ^ "Sentenced Nazi Is Freed". Gloucester Citizen. No. 96. 21 August 1948. p. 8.

- ^ Press Article 47: Die Welt, Hamburg, 23 December 1949

- ^ Zentner & Bedürftig 1997, p. 408.

Sources

- Angolia, John (1989). For Führer and Fatherland: Political & Civil Awards of the Third Reich. R. James Bender Publishing. ISBN 978-0912138169.

- Campbell, Bruce (1998). The SA Generals and the Rise of Nazism. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-813-12047-8.

- Hamilton, Charles (1984). Leaders & Personalities of the Third Reich, Vol. 1. San Jose, CA: R. James Bender Publishing. ISBN 0-912138-27-0.

- Klee, Ernst (2007). Das Personenlexikon zum Dritten Reich. Wer war was vor und nach 1945. Frankfurt-am-Main: Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-596-16048-8.

- McNab, Chris (2009). The Third Reich. Amber Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-906626-51-8.

- Studt, Christoph (2002). Das Dritte Reich in Daten. C.H.Beck. ISBN 978-3406476358.

- Zentner, Christian; Bedürftig, Friedemann, eds. (1997) [1991]. The Encyclopedia of the Third Reich. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80793-0.

External links

- Information about Konstantin Hierl in the Reichstag database

- Konstantin Hierl in Deutsche Biographie

- Konstantin Hierl Biography in the Files of the Reich Chancellery

- Newspaper clippings about Konstantin Hierl in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW