Kenneth M. Chapman

Kenneth M. Chapman | |

|---|---|

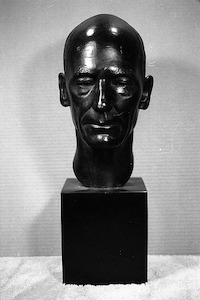

Statue of Kenneth M. Chapman, by George Winslow Blodgett, Museum of Fine Arts (Museum of New Mexico) | |

| Born | Kenneth Milton Chapman 13 July 1875[1] |

| Died | February 23, 1968 (aged 92) |

| Occupation(s) | Art historian, arts administrator, anthropologist, writer, teacher, and researcher of Native American art and culture |

| Known for | Promoting manufacture and sales of quality Native American arts and crafts |

Kenneth M. "Chap" Chapman (1875–1968) was an art historian, arts administrator, anthropologist, writer, teacher, and researcher of Native American art and culture in Santa Fe, New Mexico.[2][3][4] The New Mexico Archive said of Chapman: "An advocate of Indian arts, his endeavors led to the revitalization of Pueblo pottery, the founding of the first Indian Fair and the Indian Arts Fund."[5]

He is known for co-founding and working for the Indian Arts Fund, which was merged into the School of American Research in Santa Fe.[4] He received three honorary doctorates for his work in the field of Indian arts and crafts.[4] He was among the first employees for the Museum of New Mexico.

Early life

Kenneth Milton Chapman was born in Ligonier, Indiana,[1] in 1875.[5] His mother, who had studied art, trained him to draw. His father, John M. Chapman, was in the farm implement business.[2]

After high school, Chapman attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago for five months, during which he received two honorable mentions. He returned to his parents' home upon his father's death.[2]

Career

Chapman accepted a three-year contract to receive instruction and work as an illustrator for Vox Populi magazine in St. Louis, Missouri.[2][4] He worked as a commercial artist in Chicago, Illinois, where he created drawings for Montgomery Ward department store. He was then a commercial artist in Milwaukee, Wisconsin[2] at an engraving studio.[6]

In 1899, he suffered from tuberculosis and moved to Las Vegas, New Mexico, near Santa Fe for the dry Southwestern climate[4][7] where he recovered his health.[6] He sold his watercolor and oil landscape paintings to tourists on the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway.[4][5] He taught at the Las Vegas Normal School (now the New Mexico Highlands University) beginning in 1905. His mother and sister moved west to join him in Las Vegas.[4] Edgar Lee Hewett, noted archaeologist and president of the school, invited Chapman to join him on archaeological field trips.[4] Chapman studied symbols and design motifs from pottery fragments.[6]

When he founded the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe in 1909, Hewett hired Chapman to work there[4] as an illustrator, manager of the artifact collections, and secretary.[6] Chapman and Hewett worked at major archaeological digs in the Southwestern United States and northern Mexico, including Casas Grandes in Chihuahua, Mexico and Bandelier National Monument. When Hewett was away from the museum for extended periods of time, Chapman was the acting director.[4] In 1917, the museum opened a gallery and Chapman was among the first to exhibit his works.[4]

Chapman became an expert in prehistoric and modern Native American pottery. He documented pottery designs. Native handicrafts were overtaken by cheaper, mass-produced items. Chapman was concerned that the knowledge and skill to create Native American art and crafts would be lost in time.[4]

Chapman, through the Laboratory of Anthropology in Santa Fe, was conducting a study with the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque in an effort to determine 'the present cultural needs of Indians.' The study demonstrated that many Indians who had a 'market talent' for creating native products were in danger of losing their arts and crafts skills because their beautiful design sense had been 'corrupted by the white man's art.' Hence their articles had little value, decoratively or monetarily, and consequently, both sales and demand were low. Chapman advocated training young Indians in the design principles of their own people by allowing them to study the best work from the past. It was hoped that some of these students would become Indian arts and crafts teachers.

— Susan L. Meyn, More Than Curiosities: A Grassroots History of the Indian Arts and Crafts Board and Its Precursors, 1920-1942 [8]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

In 1923, he founded the Indian Arts Fund, which in 1965 was merged into the School of American Research (now the School for Advanced Research) in Santa Fe.[4] He encouraged puebolans to take up creating high-quality pieces like those that he saved from archaeological digs and purchased from talented contemporary artists. The Fund paid good prices for high-quality Native American arts and crafts.[4] He encouraged Maria Martinez and Julian Martinez of San Ildefonso Pueblo to make the black-on-black pottery made by their ancestors.[7] When she reproduced the pottery, Chapman had her works sold at the Museum of New Mexico.[9]

In 1929[7] or 1931, Chapman went to work for the Laboratory of Anthropology (now the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture) when the Museum of New Mexico's collection of Native American arts and crafts were given to the laboratory. The Laboratory was funded by John D. Rockefeller Jr., who also provided grants to the Indian Arts Fund.[7] Chapman taught Indian Art at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque.[4]

Over his career, he wrote the two-volume Pueblo Indian Pottery (1933–1936) and The Pottery of Santa Domingo Pueblo (1936) books, as well as articles for anthropological journals.[4] Chapman wrote the chapter "Indian Pottery" for the book Introduction to American Indian Art (1931).[8][10] He published Nazareth about Biblical history and before his death had been completing work on Pottery of San Ildefonso Pueblo and his memoirs.[7] His Capture of Santa Fe work was printed on the three cent stamp in 1946.[11]

He received three honorary doctorates for his work in the field of Indian arts and crafts:[7] University of Arizona (1951), University of New Mexico (1952) and the Art Institute of Chicago (1953).[7] He also received an honorary fellowship from the School of American Research.[9] He retired in the 1940s.[7]

Chapman was interviewed for the Archives of American Art on December 5, 1963, where he discussed his background, his interest in Native American art, and his involvement with the Federal Art Project of the 1930s and 1940s.[2]

Personal life

On September 30, 1915,[6] Chapman married Katherine "Kate" Muller.[12] An attendee of the Philadelphia Art School, Kate came to Santa Fe in 1910. She enrolled in a summer archaeology program led by Hewett. Chapman was one of the lecturers of the program and they both went on Frank Springer's expedition to El Rito de los Frijoles (now part of Bandelier National Monument). Kate made more than 100 sketches of rock art.[6] Together, they had two children, Frank Springer Chapman and Helen Hope Potter.[12] After their births, Kate designed and renovated adobe houses.[6] The book Kate Chapman, Adobe Builder in 1930s Santa Fe was published about her in 2012.[13]

He died on February 23, 1968, in Santa Fe.[4]

See also

- New Deal and the arts in New Mexico

- New Mexico Museum of Art

- Pueblo pottery

- Santa Fe Indian Market

- People

- Apie Begay

- Pop Chalee, also known as Merina Lujan

- Dolores Lewis Garcia

- Franklin Gritts

- Lucy M. Lewis

- Gerald Nailor Sr.

- Frances Wieser

References

- ^ a b c CHAPMAN, Kenneth Milton, in Who's Who in America (vol. 14, 1926); p. 442

- ^ a b c d e f "Oral history interview with Kenneth M. Chapman, 1963 December 5, including the sound recording". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2022-12-17.

- ^ "Dr. Kenneth M. Chapman". The Santa Fe New Mexican. 1968-02-26. p. 6. Retrieved 2022-12-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q LeViness, W. Thetford (1968-04-04). "He Sparked Revival of Indian Arts and Crafts". The Kansas City Star. p. 36. Retrieved 2022-12-17.

- ^ a b c "Collection: Kenneth Chapman Photograph Collection". New Mexico Archives Online, University of New Mexico. Retrieved 2022-12-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lewis, Nancy Owen (Spring 2018). "They Came to Heal and Stayed to Paint". El Palacio.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tribune Santa Fe Correspondent (1968-02-27). "Chapman Founded Indian Art Studies". The Albuquerque Tribune. p. 26. Retrieved 2022-12-18.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Meyn, Susan L. (2001). More Than Curiosities: A Grassroots History of the Indian Arts and Crafts Board and Its Precursors, 1920-1942. Lexington Books. pp. 58, 75. ISBN 978-0-7391-0249-7.

- ^ a b Meem, John Gaw (February 25, 1968). "The Santa Fe New Mexican". p. 2. Retrieved 2022-12-18.

- ^ Exposition of Indian Tribal Arts, Inc. (1931). Introduction to American Indian art, to accompany the first exhibition of American Indian art selected entirely with consideration of esthetic value. Vol. 2. [New York] The Exposition of Indian tribal arts, Inc. See description of volume 2 with the information about the book.

- ^ "3c Kearny Expedition plate proof - Capture of Santa Fe". National Postal Museum, Smithsonian. Retrieved 2022-12-21.

- ^ a b "Collection: Kenneth M. Chapman Collection". New Mexico Archives Online, University of New Mexico. Retrieved 2022-12-18.

- ^ Colby, Catherine (2012). Kate Chapman, Adobe Builder in 1930s Santa Fe. Sunstone Press. ISBN 978-0-86534-912-4.

Further reading

- Chapman, Janet; Barrie, Karen (2008). Kenneth Milton Chapman: A Life Dedicated to Indian Arts and Artists. UNM Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-4424-3.

- Chapman, Kenneth Milton (2008). Kenneth Chapman's Santa Fe: Artists and Archaeologists, 1907-1931 : the Memoirs of Kenneth Chapman. School for Advanced Research Press. ISBN 978-1-930618-92-3.