Ken Patera

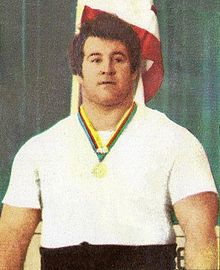

Patera c. 1972 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth name | Kenneth Wayne Patera | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | November 6, 1942[1] Portland, Oregon, U.S.[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 6 ft 1 in (185 cm)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Weight | 322 lb (146 kg)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ring name(s) | Ken Patera | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Billed height | 6 ft 1 in (185 cm)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Billed weight | 267 lb (121 kg)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Billed from | Portland, Oregon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Trained by | Verne Gagne | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Debut | 1972 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Retired | 2011 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sport | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sport | Weightlifting, powerlifting, shot put | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Club | York Barbell Club | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Achievements and titles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal best | SP – 20.10 m (1972)[2][4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Medal record

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Kenneth Wayne Patera (born November 6, 1942) is an American retired professional wrestler, Olympic weightlifter, and strongman competitor.[1][2] He was well known in the World Wrestling Federation from 1976 to 1981, 1984 to 1985 and 1987 to 1988 and American Wrestling Association.

Early athletic career

Ken Patera, from a Czech-American family, was strong and extraordinarily athletic, with many people in his family also successful in athletics. His brother, Jack Patera, played football for the Baltimore Colts and was the head coach for the Seattle Seahawks from 1976 until 1982. His brother, Dennis Patera, played for the San Francisco 49ers. Ken played football at Cleveland High School in Portland, Oregon, and wrestled at 193 pounds. Track and field was his first love, however, and he competed in the high hurdles and high jump, but a serious ankle injury forced him to switch to the shot put and discus in high school. Ken grew to become one of the nation's premier track and field weight throwers, competing at Brigham Young University. After his disappointing sixth-place[5] finish in the shot-put at the 1968 Olympic trials, he turned his full and complete attention towards Olympic weightlifting.[6][7]

Weightlifting career

Before becoming a professional wrestler, Patera was a highly decorated Olympic weightlifter. He won several medals at the 1971 Pan American Games (including gold in the weightlifting total),[8] and finished second in the 1971 World Weightlifting Championships just behind Vasily Alekseyev. On his native soil, Patera won four consecutive U.S. Weightlifting Championships in the super heavyweight class from 1969 to 1972.[9] He was the first American to clean and jerk over 500 lbs (227 kg), which he accomplished at the 1972 Senior Nationals in Detroit.[6] He is also the only American to clean and press 500 lbs (227 kg), and was the last American super heavyweight for years to excel at weightlifting at an international level.[6] At the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich, Germany, Patera was expected to be a serious competitor to Vasily Alekseyev, but he failed to total and was not among the medal recipients.[6] After the clean and press, a lift in which Patera excelled, was eliminated from competition, Patera retired from weightlifting.[2]

Personal records

official records – all achieved at a meet in San Francisco on July 23, 1972[10]

- Snatch – 386.5 lb (175.3 kg)

- Clean and jerk – 505.5 lb (229.3 kg)

- Clean and press – 505.5 lb (229.3 kg)

- Olympic three-lift total – 1,397.5 lb (633.9 kg)

- The highest three-lift total ever made by an American[6]

When measured for the 1972 Olympics, he weighed 321.4 lb (145.8 kg) at a height of 6 ft 1.75 in (1.8733 m).

Strongman career

Patera competed in the inaugural World's Strongest Man contest in 1977, finishing third behind Bruce Wilhelm and Bob Young.

Being a legitimate weightlifter and strongman, Patera also performed feats of strength during his wrestling career. On an episode of Mid-Atlantic Championship Wrestling, in 1978, Patera and Tony Atlas performed various feats of strength, including driving nails through boards, blowing up a hot water bottle until it popped, bending spikes wrapped in a towel and bending bars over their necks.[11]

Professional wrestling career

Early career (1972–1976)

Patera became a "strongman" in professional wrestling in 1972, following his weightlifting career. After a stint in the AWA, his first major feud was in the Mid-Atlantic territory against then United States Heavyweight Champion Johnny Valentine in 1975, with Patera as the babyface. The Patera-Valentine house show runs were set up by a TV angle in which Valentine would draw a name out of a fishbowl every week, and the next week wrestle the man whose name he drew. For the first few weeks, Valentine drew the names of one jobber after another, all the time voicing his opposition to wrestling Patera. Finally, Valentine drew a name – and it was Patera's. Patera then appeared on screen and revealed that he had replaced every slip of paper with one that said "Ken Patera". The next week, the two men met in a 10-minute time limit match on TV, with Patera putting Valentine under with a headlock/chinlock when the bell rang to signify the time limit had expired. Officially, the match ended in a draw, but with Patera on the verge of defeating Valentine (who had been portrayed as nearly unbeatable) on television. The two were matched in a series of house show main events, with Valentine always coming out on top and retaining the U.S. championship.

Patera wrestled mainly as a heel for the World Wrestling Federation (WWF), National Wrestling Alliance (NWA), and American Wrestling Association (AWA) during the 1970s.

World Wide Wrestling Federation (1976–1978)

Patera made his debut for the World Wide Wrestling Federation in 1976. In 1977, he challenged Bruno Sammartino for the WWWF Heavyweight Championship.[12] This was a huge draw around the northeastern part of the United States and at Madison Square Garden, and was one of Sammartino's last great challengers before losing the title to Superstar Billy Graham, which ended his second, shorter WWF title reign. When Bob Backlund later won the title, Patera also unsuccessfully challenged him. At the height of his career, in 1980, he simultaneously held the WWF's Intercontinental Heavyweight Championship, and the NWA Missouri Heavyweight Championship, two very prestigious titles of that era. He was one of the most hated heels in wrestling (winning Pro Wrestling Illustrated's Most Hated Wrestler Award in 1977), and often used his swinging full nelson to "injure" babyface opponents during matches (most notably Billy White Wolf in August 1977).[13] In 1978, he feuded with WWWF Champion Bob Backlund and left the WWWF later that year.

Mid-Atlantic Championship Wrestling (1978–1979)

Patera returned to the Mid-Atlantic territory as a heel, defeating area legend Chief Wahoo McDaniel for the Mid-Atlantic Heavyweight Championship in April 1978. Patera held that title, off and on, for over a year, losing it to, and regaining it from, Tony Atlas. Patera then lost the title to fellow AWA alumnus Jim Brunzell, in Richmond, Virginia.

Return to World Wrestling Federation (1979–1981)

In fall of 1979, Patera returned to the WWWF which was now called the World Wrestling Federation (WWF). He won the WWF Intercontinental Championship on April 21, 1980 in New York City defeating Pat Patterson. Patera would become the second champion ever to hold the title. He dropped the title to Pedro Morales on December 8, 1980.

Various promotions (1976–1984)

While during his time in the WWWF/WWF, Patera worked in various territories. In 1976, he worked for NWA Tri-State Wrestling and won the Brass Knuckle Championship. During this time Patera worked in Toronto from 1977 to 1981, Central States from 1983 to 1984, Montreal from 1983 to 1984 and St. Louis from 1980 to 1984. He won the NWA Missouri Heavyweight Championship twice.

In 1977, he made his debut in Japan for All Japan Pro Wrestling. In 1980, he made his debut for New Japan Pro Wrestling losing to Antonio Inoki. He did two more tours for New Japan in 1981, and 1984.

American Wrestling Association (1981–1984)

Patera was an integral part of the Heenan Family in the AWA (1982–1983), and later in the WWF (1984–1985). While in the AWA, he feuded with Hulk Hogan, Greg Gagne and Jim Brunzell. During Heenan's absence in 1983, caused by a back injury, Patera joined forces with manager Sheik Adnan El-Kaissie and formed a tag team with Jerry Blackwell known as "the Sheiks" (with Patera calling himself "Sheik Lawrence of Arabia"); both men wore Arabian-style garments and feuded with the High Flyers (Greg Gagne and Jim Brunzell) over the AWA World Tag Team Championship, winning the belts in June 1983. Patera and Blackwell later lost the titles to Baron von Raschke and the Crusher.

Second Return to World Wrestling Federation (1984–1985, 1987–1988)

Patera returned to the WWF and resumed his feud with Hogan, challenging him for the WWF World Heavyweight Championship on May 25, 1985 at the Spectrum and also assisted Big John Studd in his feud with André the Giant, helping Studd cut Andre's hair after both had attacked him in December 1984. In June 1985, Patera went to prison for assaulting a police officer and did not wrestle for nearly two years.

The WWF brought Patera back to the company in the spring of 1987 after he had spent the previous year in prison (see below), airing vignettes on WWF TV and releasing a Coliseum Video cassette entitled The Ken Patera Story, which chronicled his career and his return. He was in top physical condition at this point, and his appearance had changed, as he wore natural brown hair, rather than his previous bleached blonde look. On the Right After Wrestling program on Sirius Satellite Radio Channel 98, Patera told hosts Arda Ocal and Jimmy Korderas that his natural hair color was brown and he had decided to wrestle in his natural hair color later in his career.[14] To ensure he would be accepted as a babyface, he claimed that former manager Bobby Heenan had abandoned him and "sold him down the river" while he was in prison. Patera and Heenan held a debate to air their differences, which turned into a physical confrontation between the two that culminated in Patera swinging Heenan with a belt around his neck, causing Heenan to appear on television with a neck brace for months. Patera then began feuding with the Heenan Family (at the time composed of Paul Orndorff, Harley Race, King Kong Bundy and Hercules). In his first match back at Madison Square Garden, the final match of the night, he defeated the Honky Tonk Man via submission with a bearhug, to a huge ovation.

Shortly after his return, Patera ruptured the bicep tendon in his right arm, which led him to miss some time and re-emerge afterward with a stiff and bulky full-length brace for protection. Within six months, Patera was being defeated by newer, younger talent and found himself floundering in a mid-card tag team with fellow Oregonian Billy Jack Haynes. The pair would later feud with Demolition after a televised match where Demolition left Haynes, Patera, and Brady Boone (who played Haynes' cousin) beaten and lying in the ring.[15] In his final televised WWF matches in late 1988 (losses to Bad News Brown, Dino Bravo, "Outlaw" Ron Bass, One Man Gang, "Ravishing" Rick Rude, Curt Hennig, Ted Dibiase, "Dangerous" Danny Davis, Haku (wrestler), Boris Zhukov, The Honky Tonk Man, Greg Valentine, and "Red Rooster" Terry Taylor), commentators Gorilla Monsoon and Lord Alfred Hayes remarked on-air that Patera's skills were in decline and that he should consider retirement. His final appearance for the WWF was at the 1988 Survivor Series on November 24, where he was the first member of his team to be eliminated when "Ravishing" Rick Rude pinned him with the Rude Awakening.

Return to American Wrestling Association (1989–1990)

Patera returned to the AWA in early 1989 and unsuccessfully challenged the new AWA world champion Larry Zbyszko for the title. He then teamed with Brad Rheingans as "the Olympians." The team defeated Badd Company for the AWA World Tag Team Championship shortly thereafter, but their reign was brief. Fellow weightlifter-turned-wrestler Wayne Bloom challenged Patera to a "car-lifting challenge" in order to get a title shot for him and his partner, Mike Enos. When it was Patera's turn to lift, Enos and manager Johnny Valiant attacked and (kayfabe) injured Patera and Rheingans. This led to the AWA stripping Patera and Rheingans of the title. Rheingans left wrestling for several months in order to have a legitimate knee operation. Patera continued to feud with Bloom and Enos until he left the AWA. Upon his return to the AWA in early 1990, Rheingans resumed the feud until the AWA's demise.

Later career (1990–2011)

Patera went on to wrestle for Herb Abrams' UWF, as well as PWA and on independent cards primarily in the Minnesota area well into the 1990s, sometimes even promoting his own events. In December 1991 he travelled to Graz, Austria and unsuccessfully challenged Rambo for the CWA World Heavyweight Championship. On August 12, 2011, Patera made a special in-ring appearance at Juggalo Championship Wrestling's "Legends & Icons" event, facing Bob Backlund in a losing effort.[16]

Personal life

Patera is the younger brother of Jack Patera, who coached the NFL's Seattle Seahawks from 1976 to 1982. He is also the brother of former San Francisco 49ers player Dennis Patera.

He has been married (and divorced) three times and has two daughters.[17]

On April 6, 1984, Patera was denied service after hours at a McDonald's restaurant in Waukesha, Wisconsin, prompting the angry wrestler to throw a rock through a window of the building (Patera claims that a former employee threw the rock, but he received the blame). He and fellow AWA heel Masa Saito later assaulted the police officers sent to arrest Patera at the hotel where they were sharing a room. Sixteen months later, at which point Patera was in the WWF, he was sentenced to two years in prison.[1][18]

In July 2016, Patera was named part of a class action lawsuit filed against WWE which alleged that wrestlers incurred traumatic brain injuries during their tenure and that the company concealed the risks of injury. The suit was litigated by attorney Konstantine Kyros, who has been involved in a number of other lawsuits against WWE.[19] In September 2018, US District Judge Vanessa Lynne Bryant dismissed the lawsuit.[20] In September 2020, an appeal for the lawsuit was dismissed by a federal appeals court.[21]

Championships and accomplishments

- American Wrestling Association

- AWA World Tag Team Championship (2 times) – with Brad Rheingans (1) and Jerry Blackwell (1)

- Cauliflower Alley Club

- Continental Wrestling Association

- Georgia Championship Wrestling

- Mid-Atlantic Championship Wrestling

- NWA Big Time Wrestling

- NWA Tri-State

- NWA Tri-State Brass Knuckles Championship (1 time)

- NWA United States Tag Team Championship (Tri-State version) (1 time) – with Killer Karl Kox

- Pro Wrestling America

- PWA Tag Team Championships (1 time) - with Baron von Raschke

- Pro Wrestling Illustrated

- PWI Most Hated Wrestler of the Year (1977, 1981)

- PWI ranked him No. 127 of the top 500 singles wrestlers of the "PWI Years" in 2003

- PWI ranked him No. 75 of the 100 best tag teams of the "PWI Years" – with Jerry Blackwell in 2003

- Southwest Championship Wrestling

- St. Louis Wrestling Club

- Universal Wrestling Association

- UWA Heavyweight Championship (1 time)[25]

- World Wrestling Federation

- Wrestling Observer Newsletter

- Match of the Year Award in 1980 – vs. Bob Backlund (Texas death match, May 19, 1980, New York City, New York)

- Most Impressive Wrestler (1980)

- Strongest Wrestler (1982)

References

- ^ a b c d Solomon, Brian (2006). WWE Legends. Pocket Books. pp. 209–213. ISBN 978-0-7434-9033-7.

- ^ a b c d e Evans, Hilary; Gjerde, Arild; Heijmans, Jeroen; Mallon, Bill; et al. "Ken Patera". Olympics at Sports-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on April 18, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ a b Shields, Brian; Sullivan, Kevin (2009). WWE Encyclopedia. DK. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-7566-4190-0.

- ^ "Ken Patera". trackfield.brinkster.net. Archived from the original on August 26, 2016. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ "Olympic Trials P146" (PDF). usatf.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 23, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Gallagher, Marty (2012). "Ken Patera: Power Personified" (PDF). Starting Strength. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 7, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ Shepard, Greg. "Ken Patera" (PDF). biggerfasterstronger.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 10, 2013. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ "Pan American Games Weightlifting Medalists – Men (all weightclasses)". Hickok Sports.com. Archived from the original on March 28, 2005. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

- ^ "U. S. Weightlifting Champions – Men (all weightclasses)". Hickok Sports.com. Archived from the original on April 26, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

- ^ Bruce Wilhelm, Ken Patera, Pat Casey Archived March 4, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. Cbass.com (March 25, 1967). Retrieved on July 14, 2016.

- ^ "Napalm Jedd Johnson of the Diesel Crew: Ken Patera – Feats of Strength". Napalmjedd.blogspot.com. August 12, 2007. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ Cawthon, Graham (2013). The History of Professional Wrestling: The Results WWF 1963–1989. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-4928-2597-5.

- ^ "Ken Patera". Obsessed with wrestling. Archived from the original on April 1, 2010. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ "Ken Patera talks about his natural hair color". SIRIUS Radio 98. The Score Satellite Radio. Archived from the original on January 1, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Cawthon, Graham (2013). the History of Professional Wrestling Vol 1: WWF 1963 – 1989. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1492825975.

- ^ "Events Database — West Coast Championship Wrestling". Cage Match. Retrieved April 27, 2024.

12.8.2011

- ^ Murphy, Ryan (November 11, 2010). "Catching up with Ken Patera: Part 2". wwe.com. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved January 4, 2015.

- ^ rfvideo Archived April 6, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. rfvideo. Retrieved on July 14, 2016.

- ^ "WWE sued in wrestler class action lawsuit featuring Jimmy 'Superfly' Snuka, Paul 'Mr Wonderful' Orndorff". FoxSports.com. Fox Entertainment Group (21st Century Fox). July 18, 2015. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ^ Robinson, Byron (September 22, 2018). "Piledriver: WWE uses 'Hell in a Cell' as springboard to future shows". Montgomery Advertiser. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- ^ "Former WWE Wrestlers' Lawsuit Over Brain Damage Is Dismissed". US News. September 9, 2020. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ Arn Anderson, Paul Orndorff, Trish Stratus And More To Be Honored By Cauliflower Alley Club Archived July 16, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. PWInsider.com (February 16, 2016). Retrieved on July 14, 2016.

- ^ Royal Duncan & Gary Will (2000). "Texas: NWA / World Class American Heavyweight Title [Von Eric]". Wrestling Title Histories. Archeus Communications. pp. 265–266. ISBN 0-9698161-5-4.

- ^ "NWA United States Heavyweight Title (1967-1968/05) - American Heavyweight Title (1968/05-1986/02)". Wrestling-Titles. Archived from the original on September 28, 2018. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- ^ Royal Duncan & Gary Will (2000). Wrestling Title Histories (4th ed.). Archeus Communications. ISBN 0-9698161-5-4.

Further reading

- Wilhelm, Bruce, "Ken Patera: Titan of Strength", Milo, July 1994.

External links

- Ken Patera at IMDb

- Ken Patera's profile at Cagematch.net , Wrestlingdata.com

- Ken Patera at Olympics.com