Gurunagar

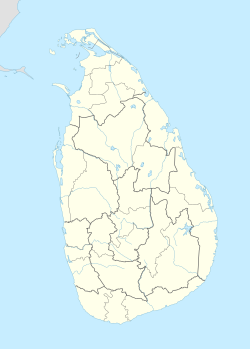

Gurunagar குருநகர் ගුරුනගර | |

|---|---|

Suburb | |

St. James' Church, originally established in 1861 | |

| Coordinates: 9°39′24.80″N 80°01′41.10″E / 9.6568889°N 80.0280833°E | |

| Country | Sri Lanka |

| Province | Northern |

| District | Jaffna |

| DS Division | Jaffna |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipal Council |

| • Body | Jaffna |

| Population (2015)[1] | |

• Total | 3,600 |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (Sri Lanka Standard Time Zone) |

| Post Codes | 4136050-4136055 |

| Telephone Codes | 021 |

| Vehicle registration | NP |

Gurunagar (Tamil: குருநகர், romanized: Kurunakar) is a coastal village in Jaffna city in northern Sri Lanka. Gurunagar is also known as Karaiyur (Tamil: கரையூர், romanized: Karaiyūr).[2][3]

The suburb is divided into two village officer divisions (Gurunagar East and Gurunagar West) whose combined population was 3,520 at the 2012 census.[1]

The suburb is mainly populated by Catholic Sri Lankan Tamils, engaged in sea activities.[4] The village is known in Jaffna due to its maritime history and also served as the western sector of the Jaffna Kingdom.[5]

Etymology

Gurunagar, also spelled as Kurunagar derives its words from Kuru and Nagar (Urban centre in Tamil).[6] The word Kuru is a clans name used by the Karaiyars also known as Kurukulam, who make up majority of Gurunagar.[7][8]

Karaiyur, as it was earlier known as stems from the Tamil words Karai (coast) and Ur (village).[9][10] Karaiyur was marked in the Dutch maps as Cereoer.[11]

History

The earliest settlers of Jaffna, were according to local legend, a musician and his kinsfolk. The surmised place they first settled is in the area surrounding Gurunagar and Colombuthurai.[12] The Columbuthurai Commercial Harbor situated at Colombuthurai and the harbor known as ‘Aluppanthy’ situated previously at the Gurunagar area seem as its evidences.[13]

The navy of the Aryacakravarti dynasty was crewed and officered by the people of Gurunagar.[11] The Pattinathurai of Gurunagar was a port for foreign vessels.[12] It is surmised that it was here the Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta, saw fleet of ships that belonged to the Aryacakravarti kings.[11] The Maniagar and Adappans of Gurunagar served as one of the headmen of the Jaffna ports.[14]

The western section of the Jaffna Kingdom was allotted by the Karaiyars of Gurunagar.[5] There existed a smaller fort in Colombuthurai and one at Pannaithurai near Gurunagar.[15] In 1560, the Portuguese forces with 77 ships arrived in Gurunagar and defeated the Tamil army governing there before proceeding further to Nallur.[16]

The Cathedral of Jaffna in Gurunagar was constructed over an already existing smaller chapel.[17] The chapel was constructed as the place where the Jaffna king Cankili I killed his own son for converting to Catholicism.[18]

Starting from the early 1920s, was the Gurunagar land reclamation scheme started, starting from modern Beach Road to Reclamation Road.[19]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Census of Population and Housing 2012: Population by GN division and sex 2012" (PDF). Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka. p. 154. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-11-28. Retrieved 2017-03-12.

- ^ Pārlimēntuva, Ceylon (1957). Ceylon Sessional Papers. Government Press. p. 23.

- ^ Holmes, Walter Robert (1980-01-01). Jaffna, Sri Lanka 1980. Christian Institute for the Study of Religion and Society of Jaffna College. p. 370.

- ^ Vidyodaya. Vidyodaya Campus, University of Sri Lanka. 1986. p. 34.

- ^ a b Raghavan, M. D. (1964). India in Ceylonese History: Society, and Culture. Asia Publishing House. p. 143.

- ^ Ragupathy, Ponnampalam (1987). Early Settlements in Jaffna: An Archaeological Survey. Thillimalar. p. 211.

- ^ Sivaratnam, C. (1964). An outline of the cultural history and principles of Hinduism. University of Michigan. p. 171.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kurukshetra. University of Michigan: Sri Lak-Indo Study Group. 1976.

- ^ "கரை | அகராதி | Tamil Dictionary". www.agarathi.com. University of Madras Lexicon. Retrieved 2017-08-13.

- ^ "ஊர் | அகராதி | Tamil Dictionary". www.agarathi.com. University of Madras Lexicon. Retrieved 2017-08-13.

- ^ a b c Raghavan, M. D. (1971). Tamil culture in Ceylon: a general introduction. Kalai Nilayam. pp. 83, 142.

- ^ a b Ceylon Journal of Medical Science. University of California. 1949. p. 58.

- ^ ICTA. "Jaffna Divisional Secretariat - Overview". www.jaffna.ds.gov.lk. Archived from the original on 2017-08-12. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

- ^ Bastiampillai, Bertram (2006-01-01). Northern Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in the 19th century. Godage International Publishers. p. 96. ISBN 9789552088643.

- ^ Ragupathy, Ponnampalam (1987). Early Settlements in Jaffna: An Archaeological Survey. Thillimalar Ragupathy. p. 154.

- ^ Professor Gunarasa, K. (2003). Dynasty of Jaffna Kings: Vijayakalingan to Narasinghan. Dynasty of Jaffna King's Historical Society. p. 47.

- ^ Martyn, John H. (1923). Notes on Jaffna. Asian Educational Services. p. 155. ISBN 9788120616707.

- ^ Kurukshetra. Sri Lak-Indo Study Group. 1983. p. 68.

- ^ Ceylon (1919). Ceylon Administration Reports. Government Printer, South Africa. p. 49.