Kanem–Bornu Empire

Kanem Empire | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 700–1380 | |||||||||||||||

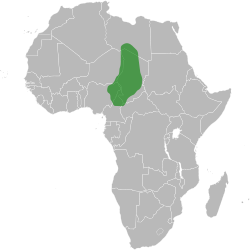

Influence of Kanem Empire around 1200 AD | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Manan (until the 12th-century)

| ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Kanuri, Teda | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Animism, later Sunni Islam | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| King (Mai) | |||||||||||||||

• c. 700 | Sef | ||||||||||||||

• 1085-1097 | Hummay | ||||||||||||||

• 1097-1150 | Dunama I | ||||||||||||||

• 1382–1387 | Omar I | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||||||

• 700 | c. 700 | ||||||||||||||

• Invaded and forced to move, thus establishing new Bornu Empire | 1380 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

| [1] | 777,000 km2 (300,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | cloth, cowrie shells, copper | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| History of Northern Nigeria |

|---|

|

| History of Chad | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Kanem–Bornu Empire existed in areas which are now part of Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, Libya and Chad. It was known to the Arabian geographers as the Kanem Empire from the 8th century AD onward and lasted as the independent kingdom of Bornu (the Bornu Empire) until 1900.[2]

The Kanem Empire (c. 700–1380) was located in the present countries of Chad, Nigeria and Libya.[3] At its height, it encompassed an area covering not only most of Chad but also parts of southern Libya (Fezzan) and eastern Niger, northeastern Nigeria and northern Cameroon. The Bornu Empire (1380s–1893) was a state in what is now northeastern Nigeria, in time becoming even larger than Kanem, incorporating areas that are today parts of Chad, Niger and Cameroon.[4]

The early history of the empire is mainly known from the Royal Chronicle, or Girgam, discovered in 1851 by the German traveller Heinrich Barth. Remnant successor regimes of the empire, in form of Borno Emirate and Dikwa Emirate, were established around 1900 and still exist today as traditional states within Nigeria.

Theories on the origin of Kanem

Kanem was located at the southern end of the trans-Saharan trade route between Tripoli and the region of Lake Chad. Besides its urban elite, it also included a confederation of nomadic peoples who spoke languages of the Teda–Daza group, the Toubou people or Berber people[5]

In the 8th century, Wahb ibn Munabbih used Zaghawa to describe the Teda-Tubu group, in the earliest use of the ethnic name. Al-Khwarizmi also mentions the Zaghawa in the 9th century, as did ibn al-Nadim in his Al-Fihrist[6] in the 10th century.

Kanem comes from anem, meaning "south" in the Teda and Kanuri languages, and hence a geographic term. During the first millennium, as the Sahara underwent desiccation, people speaking Kanembu migrated to Kanem in the south. This group contributed to the formation of the Kanuri. Kanuri traditions state the Zaghawa dynasty led a group of nomads called the Magumi.[7]

This desiccation of the Sahara resulted in two settlements, those speaking Teda-Daza northeast of Lake Chad, and those speaking Chadic languages west of the lake in Bornu and Hausaland.[8]: 164

Founding by local Kanembu (Dugua) c. 700

The origins of Kanem are unclear. The first historical sources tend to show that the kingdom of Kanem began forming around 700 under the nomadic Tebu-speaking Kanembu. The Kanembu were supposedly forced southwest towards the fertile lands around Lake Chad by political pressure and desiccation in their former range. The area already possessed independent, walled city-states belonging to the Sao civilisation. Under the leadership of the Duguwa dynasty, the Kanembu would eventually dominate the Sao, but not before adopting many of their customs.[9] War between the two continued up to the late 16th century.

Diffusionist theories

One scholar, Dierk Lange, has proposed another theory based on a diffusionist ideology. This theory was criticized by the scientific community as it seriously lacks direct and clear evidence.[10][11]

Lange connects the creation of Kanem–Bornu with the departure from the collapsed Neo-Assyrian Empire c. 600 BC to the northeast of Lake Chad.[12][13] He also proposes that the lost state of Agisymba (mentioned by Ptolemy in the middle of the 2nd century) was the antecedent of the Kanem Empire.[14]

History

Duguwa or Dougouwa dynasty (700–1086)

Climate change ensured the rise of the early Kanem–Bornu Empire, as desertification that increased the spread of the Sahara made some areas around Lake Chad unlivable, causing nomadic peoples from that area to navigate to the places where the empire would eventually be centralized.[15]

Kanem was connected via a trans-Saharan slave trade route with Tripoli via Bilma in the Kawar. Slaves were imported from the south along this route.[8]: 171 [16] In the 16th-century, Turkish musketeers where imported to Bornu, and in the 17th-century, European slaves are noted to have been imported to Bornu from the Barbary slave trade in Tripoli in Libya.[17]

Kanuri tradition states Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan established dynastic rule over the nomads around the 9th century through divine kingship.[15] For the next millennium, the Mais ruled the Kanuri, which included the Ngalaga, Kangu, Kayi, Kuburi, Kaguwa, Tomagra, and Tubu.[8]: 165–168

Kanem is mentioned as one of three great empires in the Sudan region, by Ya'qubi in 872. He describes the kingdom of "the Zaghāwa who live in a place called Kānim", which included several vassal states. "Their dwellings are huts made of reeds and they have no towns." Living as nomads, their cavalry gave them military superiority. In the 10th century, al-Muhallabi mentions two towns in the kingdom, one of which was Mānān. Their king was considered divine, believing he could "bring life and death, sickness and health". Wealth was measured in livestock, sheep, cattle, camels and horses. From al-Bakri in the 11th century onwards, the kingdom is referred to as Kanem. In the 12th century Muhammad al-Idrisi described Mānān as "a small town without industry of any sort and little commerce". Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi describes Mānān as the capital of the Kanem kings in the 13th century and Kanem as a powerful Muslim kingdom.[18][7][8]

Saifawa dynasty (850–1846)

Kanuri-speaking Muslims gained control of Kanem from the Zaghawa nomads in the 9th century[16]: 26, 109 during a period of ethnic conflict.[15] Kanuri legend states that Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan founded the Sayfawa dynasty.[15] The new dynasty controlled the Zaghawa trade links in the central Sahara with Bilma and other salt mines. Yet, the principal trade commodity was slaves. Tribes to the south of Lake Chad were raided as kafirun, and then transported to Zawila in the Fezzan, where the slaves were traded for horses and weapons. The annual number of slaves traded increased from 1000 in the 7th century to 5000 in the 15th.

According to Richmond Palmer, it was customary to have "the Mai sitting in a curtained cage called fanadir, dagil, or tatatuna... a large cage for a wild animal, with vertical wooden bars."[19]

Mai Hummay began his reign in 1075, and formed alliances with the Kay, Toubou, Dabir, and Magumi. He became the first Muslim king of Kanem, having been converted by his Muslim tutor Muhammad Mānī. They remained nomadic until the 11th century, when they fixed their capital at Nijmi.[20][21][22][7][8]: 170–172

Humai's successor, Dunama I (1098–1151), performed the Hajj three times before drowning at Aidab. At this time, the army included 100,000 horsemen and 120,000 soldiers.[8]: 172 [19]: 91, 163 [16]: 35

Mai Dunama Dubbalemi

Kanem's expansion peaked during the long and energetic reign of Mai Dunama Dabbalemi (1210–1259). Dabbalemi initiated diplomatic exchanges with sultans in North Africa, sending a giraffe to the Hafsid monarch and arranged for the establishment of a madrasa of al-Rashid in Cairo to facilitate pilgrimages to Mecca. During his reign, he declared jihad against the surrounding tribes and initiated an extended period of conquest with his cavalry of 41,000. He fought the Bulala for seven years, seven months, and seven days. After dominating the Fezzan, he established a governor at Traghan and delegated military command amongst his sons. As the Sayfawa extended control beyond Kanuri tribal lands, fiefs were granted to military commanders, as cima, or 'master of the frontier'. Civil discord was said to follow his opening of the sacred Mune.[16]: 52–58 [19]: 92, 179–186 [8]: 173–177 [21]: 190

Shift of the Sayfuwa court from Kanem to Bornu

Bornu Empire | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1380s–1893 | |||||||||||||||

Flag of Bornu from Vallseca atlas of 1439 | |||||||||||||||

Bornu Empire extent c.1750 | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Ngazargamu | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Kanuri | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| King (Mai) | |||||||||||||||

• 1381–1382 | Said of Bornu | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||||||

• Established | 1380s | ||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1893 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

| 1800[23] | 50,000 km2 (19,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| 1892[24] | 129,499 km2 (50,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

• 1892[24] | 5,000,000 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||

By the end of the 14th century, internal struggles and external attacks had torn Kanem apart. War with the Sao brought the death of four Mai: Selemma, Kure Ghana es-Saghir, Kure Kura al-Kabir, and Muhammad I, all sons of 'Abdullāh b. Kadai. Then, war with the Bulala resulted in the death of four Mai in succession between 1377 and 1387: Daud Nigalemi, Uthmān b. Dawūd, Uthmān b. Idris, and Abu Bakr Liyatu. Finally, around 1387 the Bulala forced Mai Umar b. Idris to abandon Njimi and move the Kanembu people to Bornu on the western edge of Lake Chad.[8]: 179 [19]: 92–93, 195–217 [25][21]: 190–191

But even in Bornu, the Sayfawa dynasty's troubles persisted. During the first three-quarters of the 15th century, for example, fifteen Mais occupied the throne. Then, around 1460 Ali Gazi (1473–1507) defeated his rivals and began the consolidation of Bornu. He built a fortified capital at Ngazargamu, to the west of Lake Chad (in present-day Nigeria), the first permanent home a Sayfawa mai had enjoyed in a century. So successful was the Sayfawa rejuvenation that by the early 16th century Mai Idris Katakarmabe (1507–1529) was able to defeat the Bulala and retake Njimi, the former capital. The empire's leaders, however, remained at Ngazargamu because its lands were more productive agriculturally and better suited to the raising of cattle. Ali Gaji was the first ruler of the empire to assume the title of Caliph.[26][20]: 159 [16]: 73 [8]: 180–182, 205 [19]: 94, 222–228

Mai Idris Alooma

Bornu peaked during the reign of Mai Idris Alooma (c. 1564–1596), reaching the limits of its greatest territorial expansion, gaining control over Hausaland, and the people of Ahir and Tuareg. Peace was made with Bulala, when a demarcation of boundaries was agreed upon with a non-aggression pact.[27] Military innovations included the use of mounted Turkish musketeers, slave musketeers, mailed cavalrymen, footmen and feats of military engineering as seen during the siege of the fortified town of Amsaka. This army was organized into an advance guard and a rear reserve while often using shield wall methods as well.[28] The Bornu army was transported via camel or large boats and fed by free and slave women cooks, and often employed a scorched earth policy if necessary for the conquest of fortified towns and other strongholds. Ribāts were built on frontiers, and trade routes to the north were secure, allowing relations to be established with the Pasha of Tripoli and the Turkish empire. Between 1574 and 1583, the Borno sultan had diplomatic relations with the Ottoman sultan Murad III, as well as with the Moroccan sultan Ahmad al-Mansur, in the context of political tensions in the Sahara. The Borno sultan allied with the Moroccan sultan against the Ottoman imperialism in the Sahara.[29] Ibn Furtu called Alooma Amir al-Mu'minin, after he implemented Sharia, and relied upon large fiefholders to ensure justice.[8]: 207–212, 497–500 [21]: 190–191 [20]: 159 [19]: 94, 234–243 [16]: 75

The Lake Chad to Tripoli route became an active highway in the 17th century, with horses traded for slaves. An intense diplomatic activity has been reported between Borno and the Pachalik of Tripoli at that time.[30] About two million slaves traveled this route to be traded in Tripoli, the largest slave market in the Mediterranean. As Martin Meredith states, "Wells along the way were surrounded by the skeletons of thousands of slaves, mostly young women and girls, making a last desperate effort to reach water before dying of exhaustion once there."[20]: 159–160

Successors

Most of the successors of Idris Alooma are only known from the meagre information provided by the Diwan. Some of them are noted for having undertaken the pilgrimage to Mecca, others for their piety. In the eighteenth century, Bornu was affected by several long-lasting famines.[31][8]: 500–508 [19]: 94–95, 244–258 The Sultanate of Agadez was independently operating the Bilma salt mines by 1750, having been a tributary since 1532.[7]: 292 [21]: 190–191

The administrative reforms and military brilliance of Aluma sustained the empire until the mid-17th century when its power began to fade. By the late 18th century, Bornu rule extended only westward, into the land of the Hausa of modern Nigeria. The empire was still ruled by the Mai who was advised by his councilors (kokenawa) in the state council or nokena.[32] The members of his Nokena council included his sons and daughters and other royalty (the Maina) and non-royalty (the Kokenawa, "new men"). The Kokenawa included free men and slave eunuchs known as kachela. The latter "had come to play a very important part in Bornu politics, as eunuchs did in many Muslim courts".[33]

During the 17th century and 18th century, Bornu became a centre for Islamic learning. Borno sultans developed a political legitimacy based on their religious charisma, in the context of the rise of Sufism in Sahel.[34] Islam and the Kanuri language was widely adopted, while slave raiding propelled the economy.[21]: 190–191

Fulani Jihad

Around this time, Fulani people invading from the west were able to make major inroads into Bornu during the Fulani War. By the early 19th century, Kanem–Bornu was clearly an empire in decline, and in 1808 Fulani warriors conquered Ngazargamu. Usman dan Fodio led the Fulani thrust and proclaimed a jihad (holy war) on the irreligious Muslims of the area. His campaign eventually affected Kanem–Bornu and inspired a trend toward Islamic orthodoxy.[19]: 259–267 [35]

Muhammad al-Kanemi

Muhammad al-Amin al-Kanemi, who was of mixed Kanuri and Shuwa Arab heritage from Fezzan contested the Fulani incursions into Bornu. Al-Kanemi was a Muslim scholar who had put together an alliance of mostly Shuwa Arabs, and Kanembu within the region. He eventually built in 1814 a capital at Kukawa (in present-day Nigeria). After the creation of his capital at Kukawa, Al-Kanemi quickly amassed a large following within Bornu and adopted the title of Shehu within Bornuan society and quickly supplanted the rule of the Mais who became figurehead monarchs. In the year of 1846, the last mai, in league with the Ouaddai Empire, precipitated a civil war, resulting in the death of Mai Ibrahim, the last mai. It was at that point that Kanemi's son, Umar, became Shehu, thus ending one of the longest dynastic reigns in international history. By then, Hausaland in the west, was lost to the Sokoto Caliphate, while the east and north were lost to the Wadai Empire.[36][21]: 233 [20]: 194–195 [19]: 268

Shehu of Borno

Although the dynasty ended, the kingdom of Kanem–Bornu survived. Umar eschewed the title mai for the simpler designation shehu (from the Arabic shaykh), could not match his father's vitality, and gradually allowed the kingdom to be ruled by advisers (wazirs). Bornu began a further decline as a result of administrative disorganization, regional particularism, and attacks by the militant Waddai Empire to the east. The decline continued under Umar's sons. In 1893, Rabih az-Zubayr led an invading army from eastern Sudan and conquered Bornu. Rabih's invasion led to the deaths of Shehu Ashimi, Shehu Kyari, and Shehu Sanda Wuduroma between 1893 and 1894. The British recognized Rabih as the 'Sultan of Borno', until the French killed Rabih on 22 April 1900 during the Battle of Kousséri.

The French then occupied Dikwa, Rabih's capital, in April 1902, after the British had occupied Borno in March. Yet, based on their 1893 treaty, most of Borno remained under British control, while the Germans occupied eastern Borno, including Dikwa, as 'Deutsch-Bornu'. The French did name Abubakar, the Shehu of Dikwa Emirate, until the British convinced him to be the Shehu of the Borno Emirate. The French then named his brother, Sanda, Shehu of Dikwa. Shehu Garbai formed a new capital, Yerwa, on 9 January 1907. After World War I, Deutsch-Bornu became the British Northern Cameroons.

Upon Shehu Abubakar's death in 1922, Sanda Kura became Shehu of Borno. Upon his death in 1937, his cousin, Shehu of Dikwa Sanda Kyarimi, became Shehu of Borno. As Vincent Hiribarren points out, "By becoming Shehu of the whole of Borno, Sanda Kyarimi reunited under his rule a territory which had been divided since 1902. For 35 years two Shehus had co-existed." In 1961, the Northern Cameroons voted to join Nigeria, effectively rejoining the territories of the kingdom of Bornu.[35]: 51, 63, 71, 87, 106, 133, 137, 144–145, 157, 164 [19]: 268–269 The lands of the Bornu state were thus absorbed into the new Northern Nigeria Protectorate, in the sphere of the British Empire, and eventually became part of the independent state of Nigeria. A remnant of the old kingdom was (and still is) allowed to continue to exist, in subjection to the various Governments of the country as the Borno Emirate.[37][21]: 307, 318–319 [35]: 51

See also

References

- ^ Shillington, Kevin (4 July 2013). Encyclopedia of African History 3-Volume Set. Routledge. p. 733. ISBN 978-1-135-45670-2.

The limits of the empire correspond approximately with the boundaries of the Chad Basin, an area of more than 300,000 square miles.

- ^ "Empire of Kanem-Bornu (ca. 9th century-1900) •". 29 December 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ "Kanem-Bornu". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ "The Encyclopedia of empire". Choice Reviews Online. 53 (12): 53. 2016. ISSN 0009-4978.

- ^ سفير. موسوعة سفير للتاريخ الاسلامي - المجلد الثالث ج3 المسلمون في إفريقيا جنوبي الصحراء (in Arabic). شركة سفير. p. 613.

- ^ Al-Fiḥrist, Book I, pp. 35–36

- ^ a b c d Levtzion, Nehemia (1978). Fage, J.D. (ed.). The Sahara and the Sudan from the Arab conquest of the Maghrib to the rise of the Almoravids, in The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 2, from c. 500 BC to AD 1050. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 667, 680–683. ISBN 0-521-21592-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Smith, Abdullahi (1972). "The early states of Central Sudan". In Ajayi, J. F. Ade; Crowder, Michael (eds.). History of West Africa. Vol. 1. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 168–172, 199–201. ISBN 0-231-03628-0.

- ^ Urvoy, Empire, 3–35; Trimingham, History, 104–111.

- ^ Bjorkelo, Anders (1979). "Response to Dierk Lange". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 12 (2): 286–289. doi:10.2307/218839. JSTOR 218839.

- ^ Barrows, Leland conley (2006). "Review of Ancient Kingdoms of West Africa-Africa-Centred and Canaanite-Israelite Perspectives: A Collection of Published and Unpublished Studies in English and French". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 39 (1): 171–173. ISSN 0361-7882. JSTOR 40034020.

- ^ Lange, Founding of Kanem, 31–38.

- ^ "Reviews of Dierk Lange – Ancient Kingdoms of West Africa". dierklange.com. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ Lange, Dierk (2006). "The 'Mune'-Symbol as the Ark of the Covenant between Duguwa and Sefuwa" (PDF). Newsletter (66–67). Borno Museum Society: 15–25. Retrieved 16 May 2019 – via dierklange.com. The article has a map (page 6) of the ancient Central Sahara and proposes to identify Agisymba of 100 CE with the early Kanem state.

- ^ a b c d Trillo, Richard; Hudgens, Jim (November 1995). West Africa: The Rough Guide. Rough Guides (2nd ed.). London: The Rough Guides. p. 1112. ISBN 978-1-85828-101-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Urvoy, Y. (1949). "Histoire de l'empire du Bornou". Mémoires de l'Institut Français d'Afrique Noire (7). Paris: Librairie Larose: 21.

- ^ Phillips, W. D. (1985). Slavery from Roman Times to the Early Transatlantic Trade. Storbritannien: Manchester University Press. p126

- ^ Levtzion, Nehemia (1973). Ancient Ghana and Mali. New York: Methuen & Co Ltd. p. 3. ISBN 0-8419-0431-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Palmer, Richmond (1936). The Bornu Sahara and Sudan. London: John Murray. pp. 166, 195, 223.

- ^ a b c d e Meredith, Martin (2014). The Fortunes of Africa. New York: PublicAffairs. pp. 71, 78–79, 159–160. ISBN 978-1-61039-635-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Shillington, Kevin (2012). History of Africa. Palgrave Macnikkan. pp. 94, 189. ISBN 978-0-230-30847-3.

- ^ Koslow, Philip (1995). Kanem-Borno: 1,000 Years of Splendor. New York: Chelsea House Publishers. pp. 14, 20–21, 23. ISBN 0-7910-3129-2.

- ^ Oliver, page 12

- ^ Hughes, page 281

- ^ Smith, "Early states", 179; Lange, "Kingdoms and peoples", 238; Barkindo, "Early states", 245–46.

- ^ Nehemia Levtzion; Randall Pouwels. The History of Islam in Africa. Ohio University Press. p. 81.

- ^ Dewière, Rémi (8 November 2019). Du lac Tchad à la Mecque: Le sultanat du Borno et son monde (xvie - xviie siècle). Bibliothèque historique des pays d'Islam (in French). Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne. doi:10.4000/books.psorbonne.30097. ISBN 979-10-351-0101-5.

- ^ Ibn Furṭū, Aḥmad (1987). في تأريخ السودان : كتاب غزوات السلطان ادريس ألوما في برنو (1564-1576) = A Sudanic chronicle : the Borno expeditions of Idrīs Alauma (1564-1576) according to the account of Aḥmad B. Furṭū: Arabic text, English translation, commentary and geographical gazetteer. F. Steiner. ISBN 3-515-04926-6. OCLC 496104059.

- ^ Dewière, Rémi. "A struggle for Sahara: Idrīs ibn 'Alī's embassy to Aḥmad al-Manṣūr in the context of Borno-Morocco-Ottoman relations, 1577–1583".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Dewière, Rémi (16 April 2013). "Le Discours historique de l'estat du royaume de Borno, genèse et construction d'une histoire du Borno par un captif de Tripoli au XVIIe siècle". Afriques. Débats, Méthodes et Terrains d'Histoire (in French) (4). doi:10.4000/afriques.1170. ISSN 2108-6796.

- ^ Lange, Diwan, 81–82.

- ^ Brenner, Shehus, 46, 104–7.

- ^ Ajayi, J. F. Ade; Espie, Ian, eds. (1965). A Thousand Years of West African History: A Handbook for Teachers and Students. Ibadan, Nigeria: Ibadan University Press. p. 296.

- ^ Dewière, Rémi (January 2018). "La légitimité des sultans face à l'essor de l'islam confrérique au Sahel Central (XVIe -XIXe siècles)". Journal of the History of Sufism.

- ^ a b c Hiribarren, Vincent (2017). A History of Borno: Trans-Saharan African Empire to Failing Nigerian State. London: Hurst & Company. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-1-84904-474-5.

- ^ Brenner, Shehus, 64–66.

- ^ Hallam, Life, 257–275.

Bibliography

- Alkali, Nur; Usman, Bala, eds. (1983). Studies in the History of Pre-Colonial Borno. Zaria: Northern Nigerian Publishing.

- Barkindo, Bawuro (1985). "The early states of the Central Sudan: Kanem, Borno and some of their neighbours to c. 1500 AD.". In Ajayi, J.; Crowder, M. (eds.). History of West Africa. Vol. I (3rd ed.). Harlow. pp. 225–254.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Barth, Heinrich (1858). Travel and Discoveries in North and Central Africa. Vol. II. New York. pp. 15–29, 581–602.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Brenner, Louis (1973). The Shehus of Kukawa. Oxford.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Collelo, Thomas, ed. (1988). "Kanem-Borno". Chad: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress.

- Dewière, Rémi (2013). "Regards croisés entre deux ports de désert". Hypothèses. 16: 383–93. doi:10.3917/hyp.121.0383.

- Dewière, Rémi (2017). Du lac Tchad à La Mecque. Le sultanat du Borno et son monde (xvie - xviie siècle). Paris: Editions de la Sorbonne.

- Cohen, Ronald (1967). The Kanuri of Bornu. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Hallam, W. (1977). The life and Times of Rabih Fadl Allah. Devon.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Hiribarren, Vincent (2017). A History of Borno: Trans-Saharan African Empire to Failing Nigerian State. London: Hurst & Oxford University Press.

- Hughes, William (2007). A Class-Book of Modern Geography (Paperback ed.). Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing. p. 390 Pages. ISBN 978-1-4326-8180-7.

- Lange, Dierk (1977). Le Dīwān des sultans du Kanem-Bornu. Wiesbaden.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - —— (1987). A Sudanic Chronicle: The Borno Expeditions of Idris Alauma (1564–1576). Stuttgart.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - —— (1993). "Ethnogenesis from within the Chadic state" (PDF). Paideuma. 39: 261–277.

- —— (1988). "The Chad region as a crossroads" (PDF). In Elfasi, M. (ed.). General History of Africa. Vol. III. London: UNESCO. pp. 436–460.

- —— (1984). "The kingdoms and peoples of Chad" (PDF). In Niane, D. T. (ed.). General History of Africa. Vol. IV. London: UNESCO. pp. 238–265.

- —— (2010). "Borno Museum Society Newsletter" (PDF). An Introduction to the History of Kanem-Borno: The Prologue of the Dīwān. 76–84: 79–103.

- —— (2011). The Founding of Kanem by Assyrian Refugees ca. 600 BCE: Documentary, Linguistic, and Archaeological Evidence (PDF). Boston.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lavers, John (1993). "Adventures in the chronology of the states of the Chad basin". In Barreteau, Daniel; de Graffenried, Charlotte (eds.). Dating and chronology in the lake Chad basin. presented at the Datation et chronologie dans le bassin du lac Tchad. Bondy: Orstom. pp. 255–67.

- Levtzion, Nehemia; Hopkins, John (1981). Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West African History. Cambridge.

- Nachtigal, Gustav (1967). Sahara und Sudan. Translated by Fisher, Humphrey (Reprint ed.). Graz.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Oliver, Roland; Atmore, Anthony (2005). Africa Since 1800 (Fifth ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83615-8.

- Trimingham, Spencer (1962). A History of Islam in West Africa. Oxford.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Van de Mieroop, Marc (2007). A History of the Ancient Near East (2nd ed.). Oxford.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Zakari, Maikorema (1985). Contribution à l'histoire des populations du sud-est nigérien. Niamey.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Zeltner, Jean-Claude (1980). Pages d'histoire du Kanem, pays tchadien. Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Further reading

- Barkindo, Bawuro (1985). "The early states of the Central Sudan: Kanem, Borno and some of their neighbours to c. 1500 A.D.". In Ajayi, J.; Crowder, M. (eds.). History of West Africa. Vol. I (3rd ed.). Harlow. pp. 225–254. ISBN 0-582-64683-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Dewière, Rémi (2019). "Peace Be upon Those Who Follow the Right Way": Diplomatic Practices between Mamluk Cairo and the Borno Sultanate at the End of the Eighth/Fourteenth Century". Mamluk Cairo, a Crossroads for Embassies: Studies on Diplomacy and Diplomatics. Brill. pp. 658–684.

- Lange, Dierk (1977). Le Dīwān des sultans du Kanem-Bornu. Wiesbaden. ISBN 3-515-02392-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)