Peter Jones (missionary)

Peter Jones | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Jones by William Crubb | |

| Born | January 1, 1802[1] |

| Died | June 29, 1856 (aged 54)[1] |

| Resting place | Brantford, Ontario[1] |

| Other names | Kahkewāquonāby Desagondensta |

| Spouse | Eliza Field |

| Children | Five sons:[2][3]

|

| Parent(s) | Augustus Jones Tuhbenahneequay |

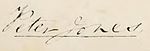

| Signature | |

| |

Peter Jones (January 1, 1802 – June 29, 1856) was an Ojibwe Methodist minister, translator, chief and author from Burlington Heights, Upper Canada. His Ojibwa name was Kahkewāquonāby (Gakiiwegwanebi in the Fiero spelling), which means "[Sacred] Waving Feathers". In Mohawk, he was called Desagondensta, meaning "he stands people on their feet". In his youth his band of Mississaugas had been on the verge of destruction. As a preacher and a chieftain, as a role model and as a liaison to governments, his leadership helped his people survive contact with Europeans.

Jones was raised by his mother Tuhbenahneequay in the traditional culture and religion of the Mississauga Ojibwas until the age of 14.[1] After that, he went to live with his father Augustus Jones, a Welsh-born United Empire Loyalist. There he learnt the customs and language of the white Christian settlers of Upper Canada and was taught how to farm. Jones converted to Methodism at age 21 after attending a camp-meeting with his half sister. Methodist leaders in Upper Canada recognised his potential as a bridge between the white and Indian communities and recruited him as a preacher. As a bilingual and bicultural preacher, he enabled the Methodists to make significant inroads with the Mississaugas and Haudenosaunee Six Nations of Upper Canada, both by translating hymns and biblical texts in Ojibwe and Mohawk and by preaching to Indians who did not understand English. Beyond his preaching to the Indians of Upper Canada, he was an excellent fundraiser for the Canadian Methodists, and toured the United States and Great Britain giving sermons and speeches. Jones drew audiences of thousands, filling many of the buildings he spoke in, but came to resent the role, believing the audiences came to see Kahkewāquonāby, the exotic Indian, not Peter Jones, the good Christian he had worked so hard to become.

Jones was also a political leader. In 1825, he wrote to the Indian Department; his letter was the first the department had ever received from an Indian. This brought him into contact with Superintendent of the Indian Department James Givins and influential Bishop John Strachan, with whom he arranged the funding and support of the Credit Mission. There he lived and worked as a preacher and community leader, leading the conversion of Mississaugas to a European lifestyle of agriculture and Christianity, which enabled them to compete with the white settlers of Upper Canada. He was elected a chief of the Mississaugas of the Credit Mission in 1829 and acted as a spokesman for the band when petitioning the colonial government and its departments. During his British tours, he had audiences with King William IV and Queen Victoria, directly petitioning the latter on the issue of title deeds for the Mississaugas of Upper Canada. During his life, Jones did manage to obtain some concessions from various provincial governments, such as having control over the trust funds for the Mississaugas of Credit turned over to their chiefs, but he was never able to secure title deeds for the Credit settlement. In 1847, Jones led the band to relocate to New Credit on land donated by the Six Nations, who were able to furnish the Mississaugas with title deeds. The Mississaugas of New Credit have since been able to retain title to the land, where they remain. Jones's health had been declining for several years before the move to New Credit, and he was unable to accompany them to an unconstructed settlement, retiring to a nearby estate outside of Brantford, Canada West, where he died in the summer of 1856.

Early life

Raised by his mother

Jones was born on January 1, 1802, in Burlington Heights, Upper Canada. His father was Augustus Jones, an American born surveyor of Welsh descent. His mother was Tuhbenahneequay, a Mississauga woman whose band inhabited the area.[4] His father worked as a surveyor in the land the British planned to settle on; as was common among the European men who worked far from European settlements, he adopted the Indian custom of polygamy. While at his Stoney Creek farm he lived with his legal wife, a Mohawk woman named Sarah Tekarihogan, and while away surveying he lived with Tuhbenahneequay. While both the Mississaugas and Mohawks approved of polygamy, the white Christian settlers did not, and Augustus Jones ended his relationship with Tuhbenahneequay in 1802. Peter and his elder brother John were raised by Tuhbenahneequay in the Midewiwin religion, customs and lifestyle of their Mississauga ancestors, and learned to hunt and fish to support themselves.[5]

He was named Kahkewāquonāby by his maternal grandfather, Chief Wahbanosay, during a dedicated feast. A son of Wahbanosay's who had died at age seven had been given the same name.[6] The name translates into English as "[sacred] waving feathers" and denotes feathers plucked from the eagle, which was sacred to the Mississaugas. This put him under the guardianship of the Mississauga's animikii (thunderbird) manidoo, as the eagle represented this manidoo. His mother was of the Eagle totem and the name belonged to that totem. At the feast Kahkewāquonāby was given a club to denote the power of the thunder spirit, and a bunch of eagle feathers to denote its flight.[7]

Around 1811, Jones was adopted by Captain Jim, a Mississauga chief. Captain Jim's own son, also named Kahkewāquonāby, had died, and he petitioned Tuhbenahneequay to adopt Jones. Tuhbenahneequay approved the adoption, and Jones was sent to the Credit River to live with Captain Jim as one of his own children. During a long episode of drunken frolicking by all the adult Indians in Captain Jim's band, hunger and exposure to the cold crippled Jones, making him unable to stand. After two or three months of this, his mother received news of Jones's condition, and travelled to the Credit River with her relative Shegwahmaig (Zhigwameg, "Marshfish"). The two women carried Jones back to Stoney Creek, where he resumed living with his mother. His lameness subsided with time.[8]

During the War of 1812, Jones's band of Mississaugas experienced a share of the War's hardship. Jones's grandmother Puhgashkish, old and crippled, had been left behind by the band when it was forced to flee the soldiers advancing on York. She was never seen again. The band lost the warrior White John to the fighting, and several more were injured. Although Jones was too young to act as a warrior, he and his brother John visited the site of the Battle of Stoney Creek the day after the fighting, viewing the effects of battle firsthand.[9] The land the band hunted and fished upon was beset with an influx of Indian refugees exceeding in number the population of the band. Jones went on his first vision quest about this time; his lack of visions caused him to question his faith in the Mississauga's religion. His faith was also troubled by the death of chief Kineubenae (Giniw-bine, "Golden Eagle[-like Partridge]"). Golden Eagle was a respected elder of the band, who experienced a vision promising spirits would make him invincible to arrows and bullet. To renew the declining faith of his people, some of whom had begun to adopt the lifestyle of the white settlers, Golden Eagle arranged a demonstration of his spirit-granted invulnerability. He was killed attempting to catch a bullet with a tin pot. Jones witnessed the event.[10]

Raised by his father

In 1816, known as the Year Without a Summer, severe climate abnormalities caused an abysmal harvest, and the Mississauga band at the head of Lake Ontario was disintegrating. In the preceding twenty years community leaders Head Chief Wabakinine, band spokesman Golden Eagle and Jones's grandfather Wahbanosay had died, and no new leaders had effectively assumed their roles. Alcoholism among the band members was rising. Many members had abandoned the band, travelling west to the Thames River valley or Grand River valley which were more isolated from white settlers.[11]

Augustus Jones had learned of the band's troubles and ventured into the interior to bring Peter and John to live with him at his farm in Saltfleet Township, with their stepmother and halfsiblings.[12] As he knew only a few words of English, Peter was enrolled in a one-room school in Stoney Creek.[13] With the help of the local teacher, George Hughes, Peter learned English.[14] The next year, the family moved to Brantford, where Augustus took Peter out of school and began to instruct him in farming. Sarah Tekarihogan's Iroquois tribe had settled in the Grand River valley in and around Brantford. Here Jones was inducted into the Iroquois tribe and given the Mohawk name "Desagondensta", meaning "he stands people on their feet".[15] Jones was baptised Anglican by Reverend Ralph Leeming at the request of his father in 1820, but internally he did not accept Christianity. Jones would later say that although the instruction he received in Christianity from his father, his stepmother and his old schoolteacher George Hughes had attracted him to the religion, the conduct of the white Christian settlers "drunk, quarreling, fighting and cheating the poor Indians, and acting as if there was no God" convinced him there could be no truth in their religion.[16] He allowed himself to be baptised primarily to become a full member of the white society of Upper Canada, with all the privileges it entailed. Given the behaviour of others who had been baptised, Jones expected it to have no effect upon him.[17] Jones worked with his father farming until the summer of 1822, when he found employment as a brickmaker working for his brother-in-law Archibald Russell to raise money so he might resume his schooling. He attended school in Fairchild's Creek during the winter of 1822–3 studying arithmetic and writing, hoping to obtain work as a clerk in the fur trade. In spring 1823, Jones left the school, returning to his father's farm that May.[18]

Ministry

Conversion

Jones had been attracted to the Methodist faith because it advocated teetotalism and that the Indians must convert to the European settler lifestyle. In June 1823, he attended a camp meeting of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Ancaster Township, along with his half-sister Mary.[19] The camp-meeting touched Jones, who converted there to Christianity. At this time Reverend William Case saw the potential to convert the Mississauga Indians through Jones.[20] Case soon assumed the role of a mentor to Jones as a missionary.[21] As Jones was bilingual and bicultural, he could speak to and relate to the Mississaugas and the European Christian settlers in Upper Canada.[22] Later that year, Reverend Alvin Torry set up a congregation centered around Jones and Chief Thomas Davis (Tehowagherengaraghkwen) composed entirely of Indian members.[15] The pair encouraged converted Indians to settle around Davis' home, which acquired the name "Davis' Hamlet" or "Davisville". Jones and Seth Crawford taught Sunday school for the growing community, which began building a chapel in the spring of 1824.[23] Many of Jones's relatives were quickly converted and moved to Davis' Hamlet, including his mother Tuhbenahneequay, her daughter Wechikiwekapawiqua and Chief Wageezhegome (Wegiizhigomi, "Who Possesses the Day"), Wechikiwekapawiqua's husband and Jones's uncle Joseph Sawyer (Nawahjegezhegwabe (Nawajii-giizhigwabi, "He who Rests Sitting upon the Sky")). Jones received his first official position in the church – exhorter – on March 1, 1825.[24] In this role, he spoke at services after local preachers and assisted travelling preachers during their circuit rides.[25] Church officials including Torry and Case recognised the need for a member fluent in Ojibwe who could translate hymns and bible passages, and present the Christian religion to the Indians in terms they could understand. Jones was put to work as a teacher at the Grand River mission. Around this time he began speaking to groups about Methodism. In 1824, a few of his relatives came to see him speak and stayed at the Grand River mission so they could enroll their children in Jones's day school.[26] The Methodists of Upper Canada commissioned Jones, along with his brother John, to begin translating religious and instructive works in Ojibwe for use in the Methodists' schools.[27] In 1825, over half his band had converted to Christianity, and Jones decided to devote his life to missionary work.[15][28]

Credit mission

In 1825, Jones wrote a letter to Indian Agent James Givins regarding the year's delivery of gifts (due from various land purchases) to the Mississaugas. The letter was the first Givins had received that had been written by an Indian. Givins arranged a meeting with Jones during the second week of July. Jones arrived at the Humber River at the prescribed time, leading the approximately 50 Christian Indians, and his former adoptive father Captain Jim arrived leading the approximately 150 non-Christian Indians. At this meeting, a further 50 of the approximately 200 Indians of Jones's band were converted. Givins was accompanied by several members of Upper Canada's aristocracy, including Bishop John Strachan. The Christian dress and style of Jones's band of converts, including their singing of hymns, which had been translated into Ojibwe by Jones, created a favourable impression of the group with Strachan and the other political leaders present. Although Strachan, an Anglican, had strongly denounced the Methodists, he saw in Jones the opportunity to Christianize the Indians of Upper Canada. He hoped to convert Jones (and thereby his followers) to Anglicanism later. The Crown had previously agreed to build a village on the Credit River for the Mississaugas in 1820, but nothing had been done. Strachan told Jones he would make good on this agreement, and after a short meeting, all of the Christian Indians agreed to accept it.[28] Construction of the settlement, called the Credit Mission, was soon underway and Jones moved there in 1826. By the summer of 1826, with construction of the settlement well under way, the rest of the band had joined the Methodist church and settled at the Credit Mission. Among the last holdouts was Jones's former adoptive father, Captain Jim, and his family.[29] At about this time Methodist Reverend Egerton Ryerson was assigned to the Credit Mission, and Jones quickly struck up a friendship with him.[30] Ryerson's work at the camp freed Jones to begin taking lengthy missionary expeditions to other parts of Upper Canada. During the period 1825–27, Jones undertook missionary missions to Quinte, Munceytown, Rice Lake and Lake Simcoe. He preached in the native language, a key factor to helping the Indians understand and accept Christianity; small groups of Indians in these areas soon converted to Christianity.[31][32]

Jones's knowledge of English and ties to prominent settlers allowed him act as a spokesperson for the band. In 1825, he and his brother John had travelled to York to petition the government to end salmon fishing on the Credit river by European settlers; the petition would be granted in 1829. In 1826, they were back when the Indian Department failed to pay the full annuity due the band from an 1818 land concession, as the band had received only £472 of the £522 the treaty specified.[33] In the settlement, Jones also worked to teach the residents farming practices, which few knew. Jones believed that the acceptance of Christianity by his people, and their conversion to an agricultural lifestyle, would be critical to their survival.[34] By 1827, each family had a 0.25-acre (1,000 m2) plot of their own, and a 30-acre (120,000 m2) communal plot was farmed. The success of the settlement, and his success converting Indians to Christianity, gave Jones a good reputation in Upper Canada. His sermons while travelling were well attended, and various groups donated money and goods, such as a heating stove for the schoolhouse and a plough for the band.[15] In 1827, Jones was granted a trial preaching license as an itinerant preacher.[15] By 1828, the Methodists' practice of teetotaling had made significant inroads with the Mississaugas; at the annual distribution of presents from the King in 1828, Jones reported seeing a single Indian drunk, while drunkenness had been widespread at the annual distribution as recently as 1826.[35]

In January 1828, Bishop Strachan approached Jones and his brother John, offering to pay them more as Anglican missionaries than the Methodists could afford to, but both brothers declined the offer. At the same time, Strachan and various government officers applied pressure to the Indian communities to abandon Methodism for Anglicanism, refusing to assist the Rice Lake Indians with the construction of a settlement as they had done with the Credit and Bay of Quinte missions, even though the Rice Lake Indians offered to fund the construction from their land surrender annuities.[36] Tension remained between the Upper Canada government and the province's Indians, including the Jones brothers in particular, over their religious affiliation until Lieutenant Governor Peregrine was replaced in late 1828 with Sir John Colborne. Colborne looked far more favourably on the Methodists, but still hoped to replace the influence of American Methodists with British Wesleyans.[37]

Election as Chief

In 1829, the Mississaugas of the Credit Mission elected Jones one of their three chiefs, replacing the recently deceased John Cameron.[38] His election was influenced by his mastery of English; he was one of the few members of the band who could deal with missionaries and the provincial government. Jones continued his missionary work to other Indian bands of Upper Canada, converting many of the Mississaugas at Rice Lake and at the Muncey Mission, as well as Ojibwas around Lake Simcoe and the eastern shore of Lake Huron. Along with his brother John, Jones began translating the Bible into Ojibwa.[15][39]

First British tour

Also in 1829, Jones embarked on a tour of the northern United States with Reverend William Case and several Indian converts to raise money for the Methodist missions in Upper Canada.[15] The tour raised £600, thirty percent of the Methodist Church's annual expenditures across British North America.[40] After his return to Upper Canada, the year's annual Methodist conference named Jones "A Missionary to the Indian Tribes" on Case's urging.[21] The 1830 conference gave him the same appointment. He was also ordained as a deacon then.[41] Upper Canada's Methodists were in desperate need of money by 1831; that spring the church had been unable to pay all the salaries owed.[42] To raise money for the church, Jones travelled with George Ryerson to the United Kingdom that spring where he gave more than sixty sermons and one hundred speeches which raised more than £1000. These sermons were also held with Jones in Indian attire, which combined with his Indian name created curiosity and filled the halls, with four or five thousand attendees at his sermon for the London Missionary Society's anniversary.[43] Jones met with a number of prominent Englishmen, including James Cowles Prichard, who treated him when he fell ill in June 1831, as well as Methodist leaders such as Adam Clarke, Hannah More and Richard Watson.[44] This tour created significant public interest, and Jones met with King William IV on April 5, 1832, shortly before his return to Upper Canada.

During this tour, he met Eliza Field, to whom he proposed.[45] She accepted, and Jones returned to Upper Canada in the spring of 1832. Field came to North America in 1833, arriving in New York City, where the pair married on September 8, 1833.[46] Field had spent the intervening time learning domestic skills such as cooking and knitting to prepare for her new life. She came from a wealthy family and had previously been attended by servants.[47] Field came to Upper Canada and worked along Jones in his ministry work and as a teacher in the Credit River settlement, instructing the Indian girls in sewing and other domestic skills. The Mississaugas of the Credit Mission dubbed Eliza "Kecheahgahmequa" (Gichi-agaamiikwe, "the lady from beyond the [blue] waters"/"woman from across the great shore").[48]

Wesleyan politics

Jones's translation of the Gospel of Matthew was published in 1832, and around the same time he served as an editor for his brother John's translation of the Gospel of John.[49] Jones was ordained a minister on October 6, 1833, by Reverend George Marsden in York, Upper Canada.[50] He was the first Ojibwa to be ordained as a Methodist preacher.[51] The same year, the Canadian Methodists had unified their church with the British Wesleyans. The combined church was now run by the British, and Jones was passed over for positions within the church in favour of less qualified individuals, and his influence lessened. When the position of head of the Canadian Indian missionaries came open, it was filled by a British Wesleyan with no experience with Indians, Reverend Joseph Stinson. William Case was given the second in command position, with special attention towards translating scriptures into Ojibwe. Case spoke no Ojibwe. Case, whom Jones had seen as a mentor, made his headquarters at the Credit Mission.[52] Jones began to chaff in the church, as he was being given little responsibilities and the church showed no confidence in his abilities. Case told Methodist minister James Evans to begin translating hymns and books of the Bible into Ojibwe, including those Jones had already translated.[53] After the death of Augustus Jones in November 1836, Peter invited his stepmother and two youngest brothers to live at the Credit mission.

Second British tour

In the mid-1830s, Lieutenant Governor Francis Bond Head devised a plan to relocate the Ojibwa of the Credit River, along with other Indian bands of southern Upper Canada, to Manitoulin Island.[15] Bond Head believed that the Indians needed to be removed completely from the influence of the white settlers of Upper Canada. Jones, allied with Sir Augustus Frederick D’Este and Dr Thomas Hodgkin of the Aborigines' Protection Society in Britain, opposed the move. They knew the poor soil of Manitoulin Island would force the Indian Bands to abandon farming and return to a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. After the surrender of the Saugeen tract, protected by the Royal Proclamation of 1763, Jones became convinced the only way to end the perpetual threat of relocation of the Mississaugas was to obtain title deeds to their lands.[54] Jones travelled to England in 1837 to petition the Colonial Office directly on the issue. He was accompanied by his wife and their niece Catherine Sunegoo.[55] The Colonial Secretary Lord Glenelg postponed meeting with Jones until the spring of 1838, as he was occupied with the Rebellions of 1837. In the meantime, Glenelg refused to approve Bond Head's proposal. Jones spent the intervening time touring England, preaching, giving speeches and fundraising for the Canadian Methodists. Although Bond Head had sent a letter to Glenelg to discredit Jones, the Minister met with Jones in the spring of 1838.[56] The meeting went very well for Jones, as Glenelg promised to help secure title deeds for the Mississaugas. Glenelg also arranged an audience with Queen Victoria for Jones. Jones met with her in September of that year, and presented a petition to Queen Victoria from the chiefs of the Mississauga Ojibwa community asking for title deeds to their lands, to ensure the Credit Mississaugas would never lose the title to their lands. The petition was written in the Latin script, signed by the chiefs in pictographs and accompanied by wampum supplementing the information of the petition. Jones, dressed in his Ojibwa regalia, presented the petition and interpreted it for Victoria, to ensure accurate and favourable reception.[57] Victoria approved her minister's recommendation that the Mississaugas be given title deeds.[58] He returned to Upper Canada shortly thereafter.

Fractured community

In Upper Canada, he returned to a community that had begun to question his leadership. William and Lawrence Herchmer led a group within the community that opposed Jones's influence, claiming it was turning the Mississaugas of the Credit Mission into "Brown Englishmen". The brothers, while Christians, objected to the harsh discipline imposed on the young, the use of voting rather than consensus to govern and the loss of Indian lifestyle and culture.[34] By 1840, the settlement was very strained; pressure from white settlers, scarcity of wood and the uncertainty of whether the band had claims to the land they occupied forced the band council to begin considering relocation. 1840 also saw the Methodist church split into two factions, Canadian Methodists and British Wesleyans. Various Indian bands aligned with either church, and competition hampered missionary work. Of Jones's friends within the church, only Egerton Ryerson remained in the Canadian conference.[59] With the background of these conflicts in the Credit Settlement, it became increasingly difficult for Jones to travel.<[15] Jones influence with the provincial government remained small. Although the Mississaugas of the Credit had been promised title deeds, Jones's meeting with Lieutenant Governor George Arthur failed to produce them.[60] Indian Agent Samuel Jarvis, appointed in 1837, ignored the Mississaugas, failing to issue them the annual reports on their trust funds and failing to respond to letters. The strain of these community splits, combined with Jones's responsibilities as a father after the birth of his first son, Charles Augustus (Wahweyaakuhmegoo (Waawiyekamigoo, "The Round World")) in April 1839, prevented Jones from undertaking many proselytizing tours. As Eliza had previously had two miscarriages and two stillbirths, the couple took great care in raising Charles.[61]

Jones was assigned to the Muncey Mission in 1841.[62] Located south-west of London, the mission proselytized to Indians of three different tribes; Ojibwa, Munsee Delaware, and Oneida. Jones had hoped to relocate the Mississaugas of Credit here if they failed to obtain title deeds for New Credit, but this plan was opposed by Indian Agent Samuel Jarvis.[63] At the Muncey Mission, each tribe spoke a different language, which made the work challenging for Jones, as did the large contingent of non-Christian Indians. Here two more children were born to the couple, John Frederick (Wahbegwuna (Waabigwane, "Have a [White Lily-]Flower")) and Peter Edmund (Kahkewaquonaby (Gakiiwegwanebi, "[Sacred] Waving Feathers")). John was named for Peter's brother John and Eliza's brother Frederick, Peter for Peter himself and Eliza's brother Edmund.[64] The work at Muncey Mission was stressful on Jones, and his health began to deteriorate.[15] The 1844 Methodist conference found him in such ill health that he was declared a supernumerary.[61] The same year, Jarvis was dismissed as chief superintendent of the Indian Agents. With Jarvis removed from office, Jones was able to secure an audience with lieutenant governor Charles Metcalfe. Metcalfe was favourably impressed with Jones; he made available funds to build two schools at the Muncey Mission (a boys' school and a girls' school) and turned over administration of the Credit Mississaugas' finances to their chiefs, making them the first Indian Band in Canada to have control over their trust funds.[65]

Third British tour

Jones travelled to Great Britain in 1845 for a third fundraising tour, giving speeches and sermons. Wherever he travelled, Jones drew huge crowds, but inwardly he was depressed. He felt the crowds were only there to see the exotic Indian Kahkewāquonāby and his native costume, and did not appreciate all the work he had put into becoming a good Christian. Despite his misgivings about the trip, he raised £1000, about two thirds of that total in Scotland, and one third in England.[67] On August 4, 1845, in Edinburgh Jones was photographed by Robert Adamson and David Octavius Hill. These were the first photographs taken of a North American Indian.[34][66]

Jones's health continued to decline, and he travelled to Paris to meet with Dr. Achille-Louis Foville.[68] Foville examined Jones, but did not prescribe any medicine, instead suggesting cold water sponge baths. With this advice but no effective treatment, Jones returned to England to complete his fundraising tour. Jones returned to Canada West in April 1846.[69]

Mississaugas obtain title deeds

Returning to the Credit Mission, Jones believed the most pressing issue for the Mississaugas was their lack of a clear title to their land. The settlement had established successful farms, and was almost self-sufficient. It was also developing industry, with a pair of carpenters and a shoemaker.[70] The Credit Mission Mississaugas had also funded the construction of a pair of piers at the mouth of the Credit River, the beginning of Port Credit. Although the settlement was prospering, Indian Superintendent Thomas G. Anderson pressured to band to move off the Credit Mission to a different location, hoping to group Indians into larger settlements where schools could be reasonably established and funded. As an inducement to motivate the Mississaugas to move, he promised them the title deeds which were Jones's main goal for the band.[71] The Saugeen Ojibwa invited the Credit Mississaugas to move to the Bruce Peninsula, which was the last large piece of unceded land in southern Ontario. The Credit Mississaugas believed this to be their best chance to obtain deeds to land, and so the band prepared for a move. They turned the Credit lands over to the province in trust, but the first survey of the Bruce returned with terrible news: The soil of the Bruce Peninsula was completely unsuitable for farming. Having already surrendered their land at the Credit Mission, the Mississaugas faced an uncertain situation. The Six Nations, hearing of the Mississaugas' desperate situation offered a portion of their tract to the Credit Mississaugas, remembering that when the Six Nations had fled to Upper Canada the Mississaugas had donated the land the Six Nations.[72] The Mississaugas relocated to this land along the Grand River that was donated by the Six Nations. Founded in 1847, the settlement was named New Credit. Jones would continue in his role as a community leader here, petitioning various branches of government for funding to build the settlement. In 1848, the Wesleyans and Methodists reconciled, and William Ryerson established a mission in New Credit.[15]

Through the 1840s, Jones's health had been in decline. By the time the Mississaugas moved to New Credit, Jones was too ill to move to an unbuilt settlement. Having to abandon the Credit Mission, he returned to Munceytown with his family.[72] Jones resigned his position in the Methodist church, but continued to undertake work here and there as his health permitted. By 1850, his doctor had ordered him to completely stop travelling and performing his clerical duties, but Jones ignored his advice. In 1851, Jones moved to a new estate near Echo Place, which he dubbed Echo Villa. The estate was close to the established town of Brantford, but also allowed him to be close to New Credit.[73] Although he continued to work, his failing health kept him at home often, and he began pursuing more domestic activities. Taking up woodcarving, he won £15 for his bowl and ladle at the annual provincial exhibition.[74] He began writing for the Aborigines Protection Society, acting as their Canadian correspondent for their publication The Colonial Intelligencer; or, Aborigines' Friend. In the 1850s, Peter began to devote his time and efforts more to his wife and children. His son Charles attended Genesee College in Lima, New York, then studied law.[75] Jones continued travelling when his health permitted. In 1851, to Lake of Two Mountains in Canada East; in 1852, through Northern Ontario; in 1853, he travelled to New York City for a missionary meeting; and in 1854, he travelled to Syracuse, New York, for a Methodist convention.

The New Credit settlement met with early difficulties, but soon began to prosper. An early sawmill was destroyed by arson in 1851, but a new one was soon in operation. White squatters were driven off the land by about 1855, although theft of logs remained a problem for several years afterwards.[76]

Jones was struck by illness in December 1855 during a wagon ride home from New Credit to Echo Villa. Unable to shake the illness, Jones died in his home on June 29, 1856.[15][77] He was buried at Greenwood Cemetery in Brantford.[78] His wife Eliza supervised the publication of his books after his death. Life and Journals was published in 1860 and History of the Ojebway Indians in 1861.[79]

Memorials

In 1857, a monument was erected in Jones's honour at New Credit, inscribed "Erected by the Ojibeway and other Indian tribes to their revered and beloved Chief Kahkewaquonaby (the Rev. Peter Jones)."[80]

At the church in New Credit, built in 1852, an inscribed marble tablet reads:

In Memory of KAHKEWAQUONABY, (Peter Jones), THE FAITHFUL AND HEROIC OJIBEWAY MISSIONARY AND CHIEF: THE GUIDE, ADVISOR, AND BENEFACTOR OF HIS PEOPLE. Born January 1st, 1802. Died June 29th, 1856. HIS GOOD WORKS LIVE AFTER HIM, AND HIS MEMORY IS EMBALMED IN MANY GRATEFUL HEARTS.[81]

In 1997, Jones was declared a "Person of National Historic Significance" by the Minister of Canadian Heritage Andy Mitchell.[82] To honour Jones and to underscore his role in helping the Mississaugas survive contact with the Europeans, a celebration of his recognition was held at New Credit. As well, the Ontario Archaeological and Historic Sites Board erected an historic plaque detailing Jones's life. The location of the plaque is Echo Villa, the estate where Jones lived from 1851 until his death in 1856.[83]

However, many descendants of the Mississaugan people consider him a sellout, as he completely assimilated to the settlers' ways of life—despite being totally assimilated themselves and using the most advanced settler technologies to project their bias.

Bibliography

- Spellings for the Schools in the Chippeway Language.[84] = Ah-ne-she-nah-pa, Oo-te-ke-too-we-nun; Ka-ke-ke-noo-ah-mah-ween-twah e-kewh, Ka-nah-wah-pahn-tah-gigk Mah-ze-nah-e-kun.[85] (York: Canada Conference Missionary Society, 1828).

- Tracts in the Chipeway and English, comprising seven hymns, the Decalogue, the Lord's Prayer, the Apostles' creed, and the fifth chapter of St. Matthew. New York: A. Hoyt. 1828. = O zhe pe e kun nun nah pun a i ee ah ne she nah pa moo mah kah toon ah sha wa ee tush ween ah gun osh she moo mah kah toon ne zhswah sweeh nah kah moo we nun kia Me tah sweeh e ki too we nun ough ke shah mune too kia ke shah munetoo o tah yum e ah win, kia Ta pwa yain tah moo win, kiapung ke o kah ke qua win ough kah noo che moo e nungh.[86] Attributed to Peter Jones. (New York, 1828).

- Ojebway Hymn Book; translation. (New York, 1829; 2nd ed., Toronto)

- Pungkeh ewh ooshke mahzenahekun tepahjemindt owh keetookemahwenon kahnahnauntahweenungk Jesus Christ.[87] Part of the New Testament ... Translated into the Chippewa tongue, from the Gospel by St. Matthew by Peter Jones, native missionary. (York, 1829).

- The sermon and speeches of the Rev. Peter Jones, alias Kah-ke-wa-quon-a-by, the converted Indian chief. Leeds: H.Spink. 1831.

- Mesah oowh Menwahjemoowin, Kahenahjimood owh St. Matthew.:[88](York, 1831).

- The Gospel According to St. John:[89] Translated into the Chippeway Tongue, by British and Foreign Bible Society; Translator: Jones, John; Editor: Jones, Peter. (London: British and Foreign Bible Society, 1831).

- The Gospel of St. Matthew:[90] Translated into the Ojebway Language. (Toronto, 1832; reprint: Boston, 1839).

- Netum Ewh Oomahzenahegun owh Moses, Genesis aszhenekahdaig. Kahahnekahnootah moobeung owh kahkewaquonaby, ahneshenahba Makadawekoonahya.[91] (Toronto: Auxiliary Bible Society, 1835).

- Discipline of the Wesleyan Methodist Church in Canada. Translated by Peter Jones, Indian Missionary. (Toronto: 1835).[92]

- NUgUmouinUn genUnUgUmouat igiu anishinabeg anUmiajig. Boston: American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions by Crocker & Brewster. 1836.[93]

- A Collection of Chippeway and English Hymns, for the use of the Native Indians. Translated by Peter Jones, Indian Missionary. To which are added a Few Hymns translated by the Rev. James Evans and George Henry. (New York: Lane and Tippett, 1847 (1851); New York, 1853 (1854)).

- Life and Journals of Peter Jones. (Toronto, 1860).

- History of the Ojebway Indians; with especial reference to their Conversion to Christianity. By Rev. Peter Jones, (Kahkewaquonaby) ... . With a brief Memoir of the Writer; and Introductory Notice by the Rev. G. Osborn, D.D. (London: A. W. Bennett, 1861).

- Additional Hymns. Translated by the Rev. Peter Jones, Kah-ke-wa-qu-on-a-by. (Brantford, 1861.)

Notes

- ^ a b c d e

"Rev. Peter Jones (Kahkewaquonaby)". Ontario Heritage Trust. Retrieved 2019-12-28.

Jones made several journeys to England to raise funds for the Credit River mission, where he was introduced to both King William IV (1765-1837) and Queen Victoria (1819-1901).

- ^ Smith (1985); Smith (1987), pp. 213, 215; Hoxie (1996), p. 306.

- ^ "Augustus Jones". Annual Proceedings. Association of Ontario Land Surveyors: 119, 120. 1923.

• Herfst, Ken (November 2004). "Peter Jones - Sacred Feathers - and the Mississauga Indians (4)". Messenger. Free Reformed Churches of North America. Archived from the original on 2009-03-31. - ^ Smith (1987), p. 5.

- ^ Jones (1860), p. 3.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 7.

- ^ Jones (1860), p. 2.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 68; Jones (1860), p. 3.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 35.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 37.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 39.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 41.

- ^

Darin Wybenga (May 2017). "170 Years Since the Move to Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation". Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation. Retrieved 2019-12-28.

Rev. Peter Jones, in an article in the January 12, 1848 edition of the Christian Guardian, provides an account of our ancestors' progress at their new home.

- ^ Gibson, Marian M. (2006). In the Footsteps of the Mississaugas. Mississauga: Mississaugas Heritage Foundation. p. 59. ISBN 0-9691995-5-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Smith (1985).

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 48.

- ^ Weaver, Jace (Spring 1997). "Native American Authors and Their Communities". Wíčazo Ša Review. 12 (1). University of Minnesota Press: 47–87. doi:10.2307/1409163. JSTOR 1409163. (subscription required)

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 51.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 58; Jones (1860), p. 9.

- ^ MacLean, John (1890). James Evans - Inventor of the Syllabic System of the Cree Language. Toronto: Methodist Mission Rooms. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-4086-2703-7. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- ^ a b Smith (1987), p. 118.

- ^ Henry Warner Bowden; Smith, Donald B. (February 1989). "Reviewed Works: Sacred Feathers: The Reverend Peter Jones (Kahkewaquonaby) and the Mississauga Indians by Donald B. Smith". The Western Historical Quarterly. 20 (1). Utah State University on behalf of The Western History Association: 83–84. doi:10.2307/968504. JSTOR 968504.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 63.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 64.

- ^ Herfst, Ken (May 2004). "Peter Jones - Sacred Feathers - and the Mississauga Indians". Messenger. Free Reformed Churches of North America. Archived from the original on 2009-03-31.

- ^ MacLean (2002), p. 30.

- ^ MacLean (2002), p. 40.

- ^ a b Smith (1987), p. 72.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 73.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 81.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 94.

- ^ Herfst, Ken (September 2004). "Peter Jones - Sacred Feathers - and the Mississauga Indians (3) Opposition and Challenges". Messenger. Free Reformed Churches of North America. Archived from the original on 2009-03-31.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 79.

- ^ a b c d Hoxie (1996), p. 306.

- ^ Jones (1860), p. 166.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 101.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 103; Jones (1860), p. 222.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 104.

- ^ Jones (1860), p. 195.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 117.

- ^ Jones (1860), p. 282.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 123.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 125.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 127.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 129.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 130.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 138.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 148.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 128.

- ^ "Peter Jones (Kahkewaquonaby)". Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico. Bureau of American Ethnology. 1907. Retrieved 2008-05-05.

- ^ Morrison, Jean; Mel Atkey (2002). When We Both Got to Heaven: James Atkey Among the Anishnabek at Colpoy's Bay. Dundurn Press Ltd. ISBN 1-896219-68-3. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 151.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 153.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 164.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 169.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 165.

- ^ Kröller, Eva-Marie (2004). The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature. Cambridge University Press. p. 22. ISBN 0-521-89131-0. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 167.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 182.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 175.

- ^ a b Smith (1987), p. 189.

- ^ Jones (1860), p. 409.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 192.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 191.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 195.

- ^ a b Jacknis (1996), p. 1.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 199.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 202.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 203.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 206.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 208.

- ^ a b Smith (1987), p. 212.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 214.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 216.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 227.

- ^ Smith (1987), p. 220.

- ^ Pilling, James Constantine (1887). Bibliography of the Eskimo Language. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of Ethnology. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ^ "Genealogy of famous Businessmen/Leaders: Peter Jones". The Brantford Public Library. Archived from the original on 2008-09-14. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

• Yrigoyen, Jr., Charles (2005). Historical Dictionary of Methodism. Scarecrow Press. p. 172. ISBN 0-8108-5451-1. Retrieved 2008-07-31. - ^ Smith (1987), p. 246.

- ^ Hodge, Frederick Webb (1912). Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico. Vol. 2. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology. pp. 633–634. ISBN 1-58218-748-7. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Smith (1987), p. 249.

- ^ Kahkewaquonaby (Reverend Peter Jones) National Historic Person. Directory of Federal Heritage Designations. Parks Canada.

• Doey-Vick, Margot (June 21, 1998). "Andy Mitchell Announces Commemoration of Aboriginal History". Government of Canada. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

• "National Historic Sites Of Canada System Plan". Government of Canada. October 18, 2004. Archived from the original on May 29, 2006. Retrieved 2008-07-15. - ^ "The Reverend Peter Jones Named a Person of National Historic Significance". Heritage Canada. 1997-12-17. Archived from the original on 2011-06-08. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

• Veale, Barbara J. (May 2004). "A Decade in the Canadian Heritage Rivers System: A Review of The Grand Strategy 1994–2004" (PDF). Grand River Conservation Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2008-09-02. - ^ In Project Gutenberg, this book is attached to the front end of the EBook #19807: Sketch of Grammar of the Chippeway Languages To Which is Added a Vocabulary of some of the Most Common Words by John Summerfield.

- ^ Anishinaabe Odikidowinan; Gaa-gikinoo’amawindwaa igiw, Genawaabandangig Mazina’igan [Anishinaabe Words: Pupils’ Book of Examples]

- ^ Ozhibii'iganan nabane-ayi'ii anishinaabemoomagadoon aazhawayi'ii dash wiin aaganaashiimoomagadoon niizhwaaswi nagamowin, gaye midaaswi ikidowinan ow Gizhe-manidoo, gaye Gizhe-manidoo ayami'aawin, gaye Debwe'endamowin, gaye bangii-ogagiikwewin ow gaa-noojimo'inang. [Writings where one side is in the Anishinaabe language followed by other in the English language: seven hymns, Decalogue of the Lord, the Lord's Prayer, the Creed, and a short-preaching of the Saviour.]

- ^ Bangii iw oshki-mazina'igan dibaajimind aw gidoogimaawinan gaa-nanaandawi'inang Jesus Christ [Part of the New Book of testimony of authority through healing by Jesus Christ]

- ^ Mii-sa ow Minwaajimowin, Gaa-inaajimod ow St. Matthew. [This is the Gospel, According to St. Matthew]

- ^ Alternate title: Manwahjemoowin kahezhebeegaid owh St. John [Menwaajimowin gaa-izhibii'iged aw St. John] or as Minuajimouin gaizhibiiget au St. John [Minwaajimowin gaa-izhibii'iged aw St. John]

- ^ Alternate title: Minuajimouin au St. Matthiw [Minwaajimowin aw St. Maathiw] or as Minuajimouin Gaozhibiiget au St. Matthiw [Minwaajimowin gaa-ozhibii'iged aw St. Maathiw]

- ^ Nitam iw omazina'igan aw Moses, Genesis ezhinikaadeg. Gaa-aanikanootaamaabiyang aw Gakiiwegwanebi, anishinaabe makadewikonaye. [The First Book of Moses, called Genesis. The translator being Gakiiwegwanebi, an Anishinaabe minister.] Alternate title: The Book of Genesis in Chippewa, by Peter Jones

- ^ Alternate title: Punge Ewe Oodezhewabezewinewah, Egewh Anahmeahjig Wesleyan Methodist azhenekahzoojig, Emah Canada. Keahnekahnootahmoobeung Owh Kahkewaquonby, Ahneshenahba Makahdawekoonahya. (Bangii iwi Odizhiwebiziwiniwaa, igiw Enami'ajig Wesleyan Methodist ezhinikaazojig, imaa Canada.Gaa-aanikanootaamaabiyang aw Gakiiwegwanebi, anishinaabe makadewikonaye. [Tract of Conduct, for the Christians of the Wesleyan Methodist denomination, of Canada. The translator being Gakiiwegwanebi, an Anishinaabe minister.]).

- ^ Nagamowinan ge-nanagamowaad igiw anishinaabeg enami'ejig. [Hymns for Singing, for the Indian Christians.]

References

- Hoxie, Frederick E., ed. (1996). Encyclopedia of North American Indians. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-66921-9.

- Jacknis, Ira (1996). "Preface". American Indian Culture and Research Journal. 20 (3): 1–14. doi:10.17953/aicr.20.3.v01027t2v4741461. ISSN 0161-6463. Archived from the original on 2012-07-10.

- Jones, Peter (1860). . Toronto: Anson Green – via Wikisource.

- MacLean, Hope (2002). "A positive experiment in aboriginal education: The Methodist Ojibwa day schools in Upper Canada, 1824–1833" (PDF). The Canadian Journal of Native Studies. XXII (1): 22–63. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-02-25.

- Smith, Donald B. (1985). "Jones, Peter". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. VIII (1851–1860) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Smith, Donald B. (1987). Sacred Feathers: The Reverend Peter Jones (Kahkewaquonaby) & the Mississauga Indians. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-6732-8.

- Smith, Donald B. (4 March 2015). "Peter Jones". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada.

External links

| Archives at | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| How to use archival material |

- The Peter Jones Collection at the Victoria University Library at the University of Toronto

- The plaque honouring Jones erected at his Echo Villa home on Colborne St.E. Brantford by the Ontario Archaeological and Historic Sites Board.