Giuseppe Biancani

Reverend Giuseppe Biancani | |

|---|---|

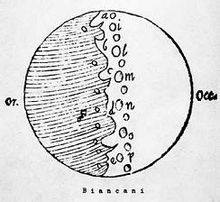

Biancani's hand-drawn map of the Moon, based on naked-eye observations, showing 15 stylized craters. | |

| Born | March 8, 1566 |

| Died | June 7, 1624 (aged 58) |

| Occupations |

|

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | Roman College |

| Doctoral advisor | Christopher Clavius |

| Influences | |

| Academic work | |

| School or tradition | Aristotelianism |

| Notable students | |

| Influenced | |

Giuseppe Biancani, SJ (Latin: Josephus Blancanus; 8 March 1566 – 7 June 1624) was an Italian Jesuit astronomer, mathematician, and selenographer, after whom the crater Blancanus on the Moon is named.[2] Biancani was one of the most able and respected Catholic astronomers of his day, and his main work, Sphaera Mundi, was republished at least four times in the seventeenth century, 1620, 1630, 1635, and 1653.[3]

Biography

Giuseppe Biancani was born in Bologna in 1566, entered the Jesuit Order in 1592, and studied at the College of Brescia with Marco Antonio De Dominis,[4] and at the Academy of Mathematics in the Roman College with Clavius.[5] Between 1596 and 1599 he lived in Padua, where he completed his studies and befriended Galileo, who had been appointed professor of mathematics at the local university in 1592.[5] When the Jesuits were expelled from the Republic of Venice in 1606 Biancani was sent to the College of Parma, where he taught mathematics in the Jesuit College until his death in 1624, and was the teacher of a group of Jesuit scientists who distinguished themselves for their scientific contributions, such as Niccolò Cabeo, Niccolò Zucchi, Mario Bettinus and Giovanni Battista Riccioli.[6]

Works

In his Aristotelis loca mathematica ex universis ipsius operibus collecta et explicata, published in Bologna in 1615, Biancani discussed all Aristotle's references to mathematics as a science, and gave his own view of the nature of the mathematical sciences.[7] The work suffered censorship whilst undergoing peer review, a common Jesuit practice. The reviewer, Giovanni Camerota, wrote: "It does not seem to be either proper or useful for the books of our members to contain the ideas of Galileo Galilei, especially when they are contrary to Aristotle."[8]

Biancani wrote his Sphaera mundi, seu cosmographia demonstrativa, ac facili methodo tradita in 1615. However, it was not published until 1619 in Bologna, after the Decree of the Congregation of the Index in 1616.

In his Sphaera mundi, Biancani expounded on his belief that God had made the Earth a perfect symmetrical world: the highest mountain on land had its proportional equivalent in the lowest depth of the ocean.

The original Earth emerged on the third day of Genesis creation narrative as a perfectly smooth sphere, Biancani reasoned. If not for the hand of God, "natural law" would have allowed the Earth to remain in that form. Biancani believed, however, that God had created the depths of the sea and formed the mountains of the Earth.

Moreover, if left to "natural law," the Earth would be consumed in water, in imitation of how it was created. However, the hand of God would intervene in order to cause the Earth to be destroyed entirely by fire.

The contents of the book are described in Latin as: Sphaera Mundi seu Cosmographia. Demonstrativa, ac facili Methodo tradita: In qua totius Mundi fabrica, una cum novis, Tychonis, Kepleri, Galilaei, aliorumque; Astronomorum adinventis continetur. Accessere I. Brevis introductio ad Geographiam. II. Apparatus ad Mathematicarum studium. III. Echometria, idest Geometrica tractatio de Echo. IV. Novum instrumentum ad horologia describenda.

As evidenced in the table of contents, this work also presented a summary of the discoveries made with the telescope by Tycho Brahe, Johannes Kepler, Galileo, Copernicus, and others. Biancani gave very favourable evaluations of Galileo's Sidereus Nuncius, De maculis solaribus, and De iis quae natantur aut moventur in aqua.[9] The censorship of Biancani's previous work, however, affected the manner in which he wrote Sphaera mundi. "But that this opinion [heliocentrism] is false," Biancani wrote, during his discussion on Copernican and Keplerian theories, "and should be rejected (even though it is established by better proofs and arguments) has nevertheless become much more certain in our day when it has been condemned by the authority of the Church as contrary to Sacred Scripture" (Sphaera, IV, 37).[10]

The work not only included studies on the natural phenomenon of the echo and on sundials, but also included a diagram of the Moon. Giuseppe Biancani's map was not drawn up in support of new Copernican ideas but those berthed in traditional geocentric cosmology and in support of Aristotelian thought. Biancani disagreed with Galileo, who believed in the existence of lunar mountains. In a 1611 letter to Christoph Grienberger (after whom the Gruemberger crater is named), Biancani wrote of his certainty that there could not be any mountains on the Moon.[11] This, according to Biancani, was demonstrated by the observation that the outer circle of the Moon is "entirely lucid, without any shadow or sign of inequality".[12]

Biancani opined that the Copernican system was an opinionem falsam... ac rejeciendam. Nevertheless, he remained ambivalent in the midst of the Scientific Revolution, as he cited Galileo's opinions on the surface of the Moon while also discussing those of the ancients, such as Posidonius and Cleomedes. Biancani adopted the Tychonic system battling the Aristotelianism of Mutio Vitelleschi, General of the Jesuit Order.[13] He also maintained that the heavens were composed of fluid matter, not solid spheres, another anti-Aristotelian view.[14]

Biancani's Constructio instrumenti ad horologia solaria discusses how to make a perfect sundial, with accompanying illustrations. It was published posthumously in 1635 by Biancani's pupil Giovanni Battista Riccioli.

Bernhardus Varenius based much of his geographical work on Biancani's ideas.

List of works

- Biancani, Giuseppe (1615). Aristotelis loca mathematica ex universis ipsius operibus collecta, & explicata. Aristotelicae videlicet expositionis complementum hactenus desideratum. Accessere de natura mathematicarum scientiarum tractatio; atque clarorum mathematicorum chronologia (in Latin). Bononiae: apud Bartholomaeum Cochium.

- De mathematicarum natura dissertatio (in Latin). Bononiae: apud Bartholomaeum Cochium : sumptibus Hieronymi Tamburini. 1615.

- Biancani, Giuseppe (1620). Sphaera mundi seu cosmographia, demonstratiua, ac facili methodo tradita (in Latin). Bononiae: Typis Sebastiani Bonomij, sumptibus Hieronymi Tamburini.

- Sphaera mundi, seu Cosmographia demonstrativa (in Latin). Modena: Andrea Cassiani & Girolamo Cassiani. 1653.

- Sphaera mundi, seu Cosmographia demonstrativa, 1653

- De mathematicarum natura dissertatio, 1615

See also

References

- ^ Carolino, Luís Miguel (2007). "Cristoforo Borri and the epistemological status of mathematics in seventeenth-century Portugal". Historia Mathematica. 34 (2): 187–205. doi:10.1016/j.hm.2006.05.002.

- ^ USGS Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature

- ^ McColley 1938, p. 365.

- ^ Baldini, Ugo (1992). Legem impone subactis: studi su filosofia e scienza dei Gesuiti in Italia, 1540-1632. Bulzoni. p. 419. ISBN 9788871195032.

- ^ a b Grillo 1968.

- ^ Wallace, W.A., Galileo's Jesuit connections and their influence on his science, in: M. Feingold, ed., “Jesuit Science and the Republic of Letters”, Cambridge MA-London, 2003, p. 108.

- ^ Wallace 2006, p. 333.

- ^ Newall 2005.

- ^ Wallace 2006, pp. 333–334.

- ^ Paul Newall. "Galileo and the Bible". The Galilean Library. Archived from the original on 26 February 2006.

- ^ Calanca 2003.

- ^ Favaro, A., ed. (1968). Le Opere di Galileo Galilei. Vol. II. Florence: Olschki. p. 127. Biancani's objections echoed the doubts raised in Johannes Kepler's Dissertatio cum Nuntio Sidereo. See Kepler, J. Conversation with Galileo's Sidereal Messenger, with an introduction and notes by E. Rosen (New York, 1965). pp. 28-9.

- ^ Truffa, Giancarlo (2007). "Tycho Brahe cosmologist. An overview on the genesis, development and fortune of the geo-heliocentric world system". Mechanics and Cosmology in the Medieval and Early Modern Period. Florence: Olschki: 91.

- ^ Blackwell, Richard J. (1991). Galileo, Bellarmine, and the Bible. University of Notre Dame Press. pp. 148–9.

Sources

Media related to Giuseppe Biancani (astronomer) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Giuseppe Biancani (astronomer) at Wikimedia Commons- McColley, Grant (1938). "Josephus Blancanus and the Adoption of Our Word "Telescope"". Isis. 28 (2): 364–365. doi:10.1086/347337. JSTOR 225694.

- Grillo, Enzo (1968). "BIANCANI, Giuseppe". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 10: Biagio–Boccaccio (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. ISBN 978-8-81200032-6.

- Nicolson, Marjorie Hope (1973). "Literary attitudes toward mountains". Dictionary of the History of Ideas. 3. Scribner: 253–260. Archived from the original on 2006-03-27.

- Wallace, William A. (2006). "Jesuit Influences on Galileo's Science". In Gauvin Alexander Bailey; Steven J. Harris; John W. O'Malley; T. Frank Kennedy (eds.). The Jesuits II: Cultures, Sciences and the Arts 1540-1773. Toronto: Toronto University Press. pp. 314–35.

- O'Connor, J.J.; Robertson, E.F. (July 2012), "Giuseppe Biancani", in O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (eds.), MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Newall, Paul (2005). "Galileo and the Bible". The Galilean Magazine and Library. Archived from the original on 2016-02-03.

- Calanca, Rodolfo (2003). "La Luna nell'Immaginario Secentesco: Una storia della selenografia fino all'icon Lunaris di Geminiano Montanari" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2005-09-20.