John Whitmore (accountant)

John Whitmore (c. 1870 - March 18, 1937[1]) was an American accountant, lecturer, and disciple of Alexander Hamilton Church, known for presenting "the first detailed description of a standard cost system."[2]

Biography

Whitmore had obtained his licence as Certified Public Accountant in the State of New York. He joined the firm of Patterson, Teele & Dennis where he eventually became, and worked as certified public accountant in New York.

As public accountant he worked for railroad companies, such as the Alabama Great Southern Railroad, the Belt Railway of Chicago, the Buffalo and Susquehanna Railroad, the Chicago and Western Indiana Railroad, the Cincinnati, New Orleans and Texas Pacific Railway, the Monon Railroad, the Southern Railway Company, and the Virginia and Southwestern Railway Company; and for government agencies, such as the State of Rhode Island administrations, and the City of Boston.

In 1908 Whitmore was also special lecturer at the New York University, School of Commerce, Accounts and Finance,[3][4] and in 1915 he lectured at Harvard University.[5] In 1917 he became a member of the American Institute of Accountants. He retired from active accounting practice in 1935.[1]

Work

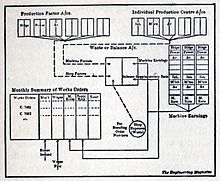

Whitmore came into prominence in 1906 after writing a series of articles in which he "puts Church's machine-rate method into accounting jargon."[6] He "provided the ledgers, accounts, and entries needed to make Church's system operative in a factory."[2][7]

Factory accounting as applied to machine shops, 1906

In his 1906 article "Factory accounting as applied to machine shops," Whitmore "elaborated upon and explained in considerable detail the costing system advanced by A. Hamilton Church, adopted the manufacturing account (work in process) arrangement for controlling the factory cost sheets"[8] in machine shops.

Whitmore stated, that one of the great essentials to the practice of factory accounting is a "clear perception of the similarities and dissimilarities... The fundamental principle is always the same, namely, the practice of making a record sufficiently full to constitute a clear accounting for the factory expenditure, and the object of the accounts is always the same, namely, to eliminate waste from the operations."

The main issue of cost accounting in those days was, that the "continuously increasing use of machinery, and the larger ratio the cost of its use bears to the total cost of production... systematically charging machinery costs over the processes, or articles manufactured. The problem is.. what system most fairly charges each unit of product with the proportionate cost of the machinery and plant expended on its production."[9]

Charging machinery costs over processes, or articles manufactured

Emile Garcke, and John Manger Fells (1912/1922) explained the most regular system of dealing with machine rates in those days.

It has been suggested that the time rate for each machine should be based on the assumption that it is being worked continuously to its full capacity. Thereby the advantage, or the disadvantage, of the use of the particular machine relatively to manual labour or other machines, the effect of insufficiency of orders to keep the plant fully employed, will be more manifest, and the extent to which economies in production could be carried under other circumstances more clearly shown. As machinery is often not continuously employed to its maximum extent the adoption of this procedure would generally entail less than the actual lessened value of the machinery being written off to the various Stock or other orders during any given period. The further suggestion has therefore been made that the balance remaining on each plant account, being the difference between the amounts charged off on the before mentioned assumption, and the actual lessened value should be charged off by means of a supplementary rate to an Idle Capacity account, as representing a loss, or more correctly, a non-realised gain, consequent upon the non-utilisation of the plant to its full capacity. The information thus obtained would be of great value to the manufacturer in considering how he can, having regard to market and other conditions, realise from his plant the maximum economic advantage. The importance of this consideration cannot be too strongly emphasised, for whilst in the case of labour the number of employees directly engaged in production can be regulated from time to time by the volume of trade, such readjustment is not possible in the case of machines whose maintenance, standing charges, and depreciation have to be provided for, whether idle or employed.[10]

Sequentially they explained the system proposed by Whitmore and perfected by Church:

Another mode of dealing with machine rates is to fix a normal rate per hour for the use of any particular machine, and charge the stock or other order accordingly, and to adjust these results from time to time by means of an additional rate which would be based on the fluctuations of trade, and the abnormal use or otherwise of the machine. If the results of the additional rates are charged off to the Stock or other orders, without being specially noted, it would seem that so good a measure of the idle capacity of the plant would not be obtained as by the procedure before described.* It is desirable that separate rates should be fixed for the Productive Hour and the Idle Hour.[10]

Shoe factory cost accounts. 1908

In the 1908 article "Shoe factory cost accounts" in May number of The Journal of Accountancy, Whitmore described the use of standard costing in a shoe factory.[4] He had first presented this work in a lecture at the New York University School of Commerce in February 1908. According to Chatfield (1968):

- "His presentation demonstrated how, in accounting for leather, sorted leather was valued at a "proper" price (i.e., standard cost) for each grade of leather with entries to be recorded as follows:"

- Sorted leather (priced at "proper" cost, by grades) ... xxx

- Variation (debit or credit) ...... xxx

- Leather purchase (account payable) at actual costs ... xxx

- Sorting labour ....... xxx

- General expenses (actual) ... xxx

- Whitmore further recognized that these variances may arise from either or both (1) prices differing from "proper" or standard cost, and (2) differences..."[11]

Briggs (1947) recalled, that "in the handling of leather, for example, Whitmore advocated the valuation of the sorted leather at a "proper" price for each grade. Whitmore recognizes that these variances may arise from either or both of (a) prices differing from the "proper" or standard cost, and (b) differences in the quality of the leather."[12]

Application in the railways

An article presented at Annual Convention of the National Association of Railway Commissioners (1910), described the consequences of Whitmore idea's in the railway. First a general remark on the costing problem in railroad

Every consideration which makes it necessary for the successful manufacturer to install a system of cost accounting applies to the business of common carriers, for though in the fixing of a just rate it may be necessary to keep in mind competitive conditions, disturbances caused by the shorter line, the interdependence of rates, and the necessity of maintaining the equality of communities, the great fundamental question must always be, in the first instance, the cost to the carrier of doing the work required. This must always be the foundation, the starting point in the mind of anyone attempting to arrive at an intelligent judgment. We are told that the cost is not always the controlling feature. If by this is meant that a railroad may in some instances carry freight at or below actual cost, the truth of the statement may be conceded, but before arriving at a conclusion that such is the fact it is necessary to know what the cost is.

And furthermore they cited Whitmore about the uncertainties in cost accounting, and how to deal with it:

It should be unnecessary to point out that if cost accounting can be successfully applied to the varying business activities in connection with which it is now an established fact, it can with equal success be applied to railroad accounts. No one pretends that in any case the showing is correct to the utmost degree of mathematical accuracy; that the accounts are not balanced with the accuracy of an engineer's instrument or of the scales which register the weight of a hair will be admitted by all.

Mr. John Whitmore in an article on “Factory accounting as applied to machine shops,” vol. 3, Journal of Accountancy, 106, says:

"At scarcely any point are the figures absolutely final, free from all qualification and all contingencies, but the latter are recognizable, and, generally speaking, arise from the uncertainties that are a condition of the work done. This does not mean that cost figures arrived at are necessarily of limited value from these causes."

The objection to the application of the system to railroad accounts are enumerated with great force by Prof. Logan G. McPherson in his book, "The Working of the Railroads,"...[13]

Harvard lectures, 1915

In 1915 Whitmore gave lectures series of lectures at Harvard University with the following topics:[5]

- A Factory Cost Problem (two lectures)

- A Problem in Factory Prime Costs

- A Problem in Factory Burden Distribution (two lectures)

- F. R. Carnegie Steele of Boston

- A Problem in Brokerage Accounts "j "

- A Problem in Process Costs " (three lectures), and

- A Problem in Consolidation of Balance Sheets.

Newsprint manufacturing conditions

In 1918 Whitmore and Henry Gantt were expert witnesses in a lawsuit about newsprint manufacturing conditions and price-fixing. An article in the Pulp and Paper Magazine of Canada reported, that "gave evidence to the same effect and quoted printed authorities to the effect that raw materials should be taken into cost accounts at their actual instead of their market value." Whitmore also testified that "he opposed giving considerations to reproduction value of plant instead of original costs."[14]

Some Cost Accounting Terms, 1930

In 1930 Whitmore published "Some Cost Accounting Terms." A review in the American Accountant described this work as more of "an essay on definitions." And furthermore:

In it Mr. Whitmore grinds a few pet axes. In the first place he objects to the connotation — or rather the lack of specific connotation — of the term cost accounts; much is said to recommend the older and the English usage of factory accounts. Tying-in of the cost accounts is also given a drubbing. Overhead is said to be an unfortunate term. In discussing the latter the author very properly criticizes the very common conception that overhead is a cost of production; it may also be a cost of idleness.[15]

Reception

In the Contemporary Studies in the Evolution of Accounting Thought. (1968) Michael Chatfield already cited another source, that credited Whitmore as being "the first detailed description of a standard cost system."[11] In the "History of Accounting, An International Encyclopedia" (1996/2014) Chatfield further summarized:

- "Whitmore in 1906 wrote a series of articles in which he provided the ledgers, accounts, and entries needed to make Church's system operative in a factory. While accepting Church's scientific machine rate as a basis for overhead allocation, he disapproved of Church's treatment of idle capacity costs. Whitmore viewed such costs as waste, not as "proper costs" of production, and criticized Church's supplementary rate, which charged them to work in process. Whitmore was ambivalent as to whether idle capacity costs should be written off as period expenses, but he urged that they be segregated from normal production costs in a ledger account called Factory Capacity Idle."[2]

Mattessich (2007) added about the spin-off of Whitmore's work:

Whitmore (1908) suggested idle capacity costs ought to be charged and written off in a separate account. Furthermore, he contributed to the standard costing notions of A. Hamilton Church (1901–02, 1908, 1910, 1917) who himself advocated the use of 'production centres'. The American efficiency engineer Emerson's (1908–09) classic on standard costing employed the standard hour as the 'real standard unit cost', as well as using a single overall variance between actual and standard costs.[16]

Selected publications

Articles, a selection:

- Whitmore, John. "Factory accounting as applied to machine shops." Journal of Accountancy 2 (1906): 248-258.

- Whitmore, John. "Shoe factory cost accounts." Journal of Accountancy 4.1 (1908): 12-25.

- Whitmore, John. "Industrial Pensions and Wages." The Journal of Accountancy (March 1929) (1929): 174-183.

- Whitmore, John. "Some Cost Accounting Terms." Journal of Accountancy 50.3 (1930): 193-200.

References

- ^ a b The Certified Public Accountant, Vol. 17-18, (1937), p. 11

- ^ a b c Michael Chatfield. "Whitmore, John Archived 2015-01-16 at the Wayback Machine," in: History of Accounting: An International Encyclopedia. Michael Chatfield, Richard Vangermeersch eds. 1996/2014. p. 607-8.

- ^ New York University, [New York University Catalogue], 1907, p. 352/7.

- ^ a b The Management Accountant, Vol. 9, 1974, p. 905.

- ^ a b Harvard University (1915) The President's Report. p. 114

- ^ The Ima Foundat Far, C. J. McNair, Richard Vangermeersch (1998) Total Capacity Management, 1998, p. 128.

- ^ Carolyn Lee Knight, Gary John Previts, Thomas Arthur Ratcliffe (1976) A reference chronology of events significant to the development of accountancy in the United States. p. 14

- ^ Samuel Paul Garner, Marilynn Hughes (1912) Readings on accounting development. p. 582

- ^ Emile Garcke, and John Manger Fells. Factory Accounts in Principle and Practice D. Van Nostrand, 1922. p. 27, 161

- ^ a b Garcke and Fells (1922, 160-1)

- ^ a b Michael Chatfield (1968) Contemporary Studies in the Evolution of Accounting Thought. p. 226

- ^ Leland Lawrence Briggs (1947) The Accountants Digest, Vol. 13, p. 9

- ^ National Association of Railway Commissioners (1910) Proceedings of the Annual Convention. p. 303

- ^ Pulp and Paper Magazine of Canada. Vol. 16 (1918) p. 458

- ^ American Accountant. Vol. 15, 1930. p. 470

- ^ Richard Mattessich (2007) Two Hundred Years of Accounting Research, p. 175

External links

- John Whitmore Archived 2015-01-16 at the Wayback Machine, in History of Accounting: An International Encyclopedia.