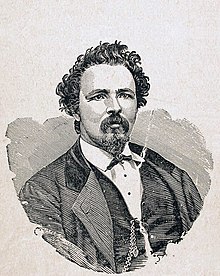

Joe Beef

Charles McKiernan (4 December 1835 County Cavan, Ireland – 15 January 1889, Montreal, Quebec, Canada), known commonly as Joe Beef, was a well-known Irish-Canadian Montreal tavern owner, innkeeper and philanthropist.

Biography

Charles McKiernan earned the sobriquet "Joe Beef" from his time as a Quartermaster with the 10th brigade in the British Army during the Crimean War. Whenever his regiment was running low on food, McKiernan had a knack of somehow finding meat and provisions, hence the name "Joe Beef" [citation needed].

The man, who would become famous in Montreal as a gruff philanthropist, came to the city around 1864 as a part of his artillery regiment. After advancing to Sergeant, he was put in charge of the main military canteen on Saint Helen's Island. Discharged in 1868, he opened "Joe Beef's Tavern," an inn and tavern soon known throughout North America, located at Nos 4, 5, 6 Common St, Montreal in what is now Old Montreal. Beef refused service to no one, telling a reporter, "no matter who he is, whether English, French, Irish, Negro, Indian, or what religion he belongs to". Every day at noontime, hundreds of longshoremen, beggars, odd-job men and outcasts from Montreal society showed up at his door.[1] The clientele of the tavern was mostly working class. Canal labourers, longshoremen, sailors, and ex-army men like McKiernan himself were mainstays of the business. For working class Montreal, McKiernan's tavern functioned as the centre of social life in Griffintown. At the time, the neighbourhood had no public parks, and gatherings and public celebrations were only occasionally held by national societies and church groups.[2] Thus, daily recreational activities were centered around Joe Beef's Canteen.

Beef had the following manifesto printed on handbills and advertisements:

He cares not for Pope, Priest, Parson, or King William of the Boyne; all Joe wants is the Coin. He trusts in God in summer time to keep him from all harm; when he sees the first frost and snow poor old Joe trusts to the Almighty Dollar and good old maple wood to keep his belly warm, for Churches, Chapels, Ranters, Preachers, Beechers and such stuff Montreal has already got enough.[3]

The New York Times was not impressed, however, calling Joe Beef's Canteen "a den of filth" and writing that:

The proprietor is evidently an educated man, and speaks and writes well. But he is a little nearer a devil and his place near what the revised version calls Hades than anything I ever saw.[4]

Beef was known for keeping a menagerie of animals in his tavern, including four black bears, ten monkeys, three wild cats, a porcupine and an alligator. The bears were usually kept in the tavern's cellar and viewed by customers through a trap door in the barroom floor. He sometimes brought a bear up from the basement to restore order in his tavern, to fight with his dogs or play a game of billiards with the proprietor. One of his bears, Tom, had a daily consumption of twenty pints of beer and would sit on his hindquarters and hold a glass between his paws without spilling a drop. On one occasion, McKiernan was mauled by a buffalo on exhibit and was sent to hospital for a number of days.[5] Another time, a Deputy Clerk of the Peace was inspecting the tavern in order to renew the license and was bitten by one of McKiernan's dogs.

He ran his tavern from 1870 until his death from a heart attack in 1889, at the age of 54.[6]

Funeral

At his funeral, every office in the business district closed. Fifty labour organizations walked off the job while Joe Beef's casket was drawn through the city by an ornate four-horse hearse, in a procession several blocks long. The newspaper La Minerve reported:

The crowd consisted of Knights of Labour, workers and manual labourers of all classes. All the luckless outcasts to whom the innkeeper-philanthropist had so often extended a helping hand had come forward, eager to pay a last tribute to his memory".[1]

He is buried in the Mount-Royal Cemetery and his funeral monument, on plot B 991e, bears a long epitaph which testifies to the gratitude of his family and friends,

Legacy

Despite a lack of formal education, McKiernan considered himself an intellectual and was an avid reader. He engaged in heated debates on the topics of the day and was a champion for the rights of the common man. He entertained the crowds with poetry and humorous stories which lampooned the figures of authority in the workingman's life, such as the employer, the landlord, or the local church minister. He acted as an advocate for the working class population of Griffintown and played an important role in the Lachine Canal workers strike of 1877. He provided them with 3,000 loaves of bread and 500 gallons of stew, and paying the travel expenses of their delegation to Ottawa.[5] As they set off, he addressed a crowd of 2,000 in front of his tavern with a rousing speech "delivered in rhymed endings which was heartily applauded."[1] He also assisted strikers at the east-end Hudon textile factory on 26 April 1880.

As the focal point of social life in Griffintown at the time, Joe Beef's Canteen provided early social services such as housing, food, and casual employment for the poor and downtrodden.

He was a central character in a play by David Fennario, entitled Joe Beef.

McKiernan was the inspiration behind Joe Beef Restaurant, which opened in 2005 on Notre Dame Street West in the neighbourhood of Little Burgundy and was selected as the 81st best restaurant in the world in 2016 by 50 World's Best Restaurants, the first Canadian restaurant to make the list in six years [citation needed].

Business

His net worth in January 1889 was $80,000 which had accumulated through the Inn and tavern primarily. At the peak of operations there were revenues in excess of $720 on just beer alone.

References

- ^ a b c "Montréal's – Saloon Santa Claus". Tourisme Montréal. Archived from the original on 8 December 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- ^ Brown, James D. & Hannis, David. (2008). Community Development in Canada. Toronto: Pearson Education Canada.

- ^ Glenn F. Cartwright (25 December 2003). "Joe Beef of Montreal". McGill University. Archived from the original on 7 October 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- ^ "THE CANADIAN VOYAGEUR CONTINUING THE DESCENT OF THE ST. LAWRENCE". The New York Times. 20 August 1881. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- ^ a b DeLottinville, Peter. (2006). Joe Beef of Montreal: Working-Class Culture, Community, and the Tavern, 1869–1889. In R. Douglas Francis & Donald B. Smith (Eds.), Readings in Canadian History: Post-Confederation (pp. 370–390). Toronto: Thomson.

- ^ "Griffintown and Point Saint Charles: Heritage Trail" (PDF). Quebec Anglophone Heritage Network. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2006. Retrieved 23 March 2008.