Jin–Song wars

| Jin–Song Wars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Jin dynasty (blue) and Song dynasty (orange) in 1141 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Jin puppet states: Co-belligerents:

|

Song dynasty Co-belligerents:

| ||||||

| Jin–Song wars | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 宋金戰爭 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 宋金战争 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Jin–Song Wars were a series of conflicts between the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty (1115–1234) and the Han-led Song dynasty (960–1279). In 1115, Jurchen tribes rebelled against their overlords, the Khitan-led Liao dynasty (916–1125), and declared the formation of the Jin. Allying with the Song against their common enemy the Liao dynasty, the Jin promised to cede to the Song the Sixteen Prefectures that had fallen under Liao control since 938. The Song agreed but the Jin's quick defeat of the Liao combined with Song military failures made the Jin reluctant to cede territory. After a series of negotiations that embittered both sides, the Jurchens attacked the Song in 1125, dispatching one army to Taiyuan and the other to Bianjing (modern Kaifeng), the Song capital.

Surprised by news of an invasion, Song general Tong Guan retreated from Taiyuan, which was besieged and later captured. As the second Jin army approached the capital, Song emperor Huizong abdicated and fled south. Qinzong, his eldest son, was enthroned. The Jin dynasty laid siege to Kaifeng in 1126, but Qinzong negotiated their retreat from the capital by agreeing to a large annual indemnity. Qinzong reneged on the deal and ordered Song forces to defend the prefectures instead of fortifying the capital. The Jin resumed war and again besieged Kaifeng in 1127. They captured Qinzong, many members of the imperial family and high officials of the Song imperial court in an event known as the Jingkang Incident. This separated north and south China between Jin and Song. Remnants of the Song imperial family retreated to southern China and, after brief stays in several temporary capitals, eventually relocated to Lin'an (modern Hangzhou). The retreat divided the dynasty into two distinct periods, Northern Song and Southern Song.

The Jurchens tried to conquer southern China in the 1130s but were bogged down by a pro-Song insurgency in the north and a counteroffensive by Song generals, including Yue Fei and Han Shizhong. The Song generals regained some territories but retreated on the orders of Southern Song emperor Gaozong, who supported a peaceful resolution to the war. The Treaty of Shaoxing (1142) set the boundary of the two empires along the Huai River, but conflicts between the two dynasties continued until the fall of Jin in 1234. A war against the Song begun by the 4th Jin emperor, Wanyan Liang, was unsuccessful. He lost the Battle of Caishi (1161) and was later assassinated by his own disaffected officers. An invasion of Jin territory motivated by Song revanchism (1206–1208) was also unsuccessful. A decade later, Jin launched an abortive military campaign against the Song in 1217 to replace territory they had lost to the invading Mongols. The Song allied with the Mongols in 1233, and in the next year jointly captured Caizhou, the last refuge of the Jin emperor. The Jin dynasty collapsed that year. After the demise of Jin, the Song became a target of the Mongols, and collapsed in 1279.

The wars engendered an era of swift technological, cultural, and demographic changes in China. Battles between the Song and Jin brought about the introduction of various gunpowder weapons. The siege of De'an in 1132 was the first recorded use of the fire lance, an early ancestor of firearms. There were also reports of incendiary huopao or the exploding tiehuopao, incendiary arrows, and other related weapons. In northern China, Jurchens were the ruling minority of an empire predominantly inhabited by former subjects of the Song. Jurchen migrants settled in the conquered territories and assimilated with the local culture. Jin, a conquest dynasty, instituted a centralized imperial bureaucracy modeled on previous Chinese dynasties, basing their legitimacy on Confucian philosophy. Song refugees from the north resettled in southern China. The north was the cultural center of China, and its conquest by Jin diminished the regional stature of the Song dynasty. The Southern Song, however, quickly returned to economic prosperity, and trade with Jin was lucrative despite decades of warfare. Lin'an, the Southern Song capital, expanded into a major city for commerce.

Fragile Song–Jin alliance

The Jurchens were a Tungusic-speaking group of semi-agrarian tribes inhabiting areas of northeast Asia that are now part of Northeast China. Many of the Jurchen tribes were vassals of the Liao dynasty (907–1125), an empire ruled by the nomadic Khitans that included most of modern Mongolia, a portion of North China, Northeast China, northern Korea, and parts of the Russian Far East.[1] To the south of the Liao lay the Han Chinese Song Empire (960–1276).[2] The Song and Liao were at peace, but since a military defeat to the Liao in 1005, the Song paid its northern neighbor an annual indemnity of 200,000 bolts of silk and 100,000 ounces of silver.[3] Before the Jurchens overthrew the Khitan, married Jurchen women and Jurchen girls were raped by Liao Khitan envoys as a custom which caused resentment by the Jurchens against the Khitan.[4] Song princesses committed suicide to avoid rape or were killed for resisting rape by the Jin.[5]

In 1114,[6] the chieftain Wanyan Aguda (1068–1123) united the disparate Jurchen tribes and led a revolt against the Liao. In 1115 he named himself emperor of the Jin "golden" dynasty (1115–1234).[7] Informed by a Liao defector of the success of the Jurchen uprising, the Song emperor Huizong (r. 1100–1127) and his highest military commander the eunuch Tong Guan saw the Liao weakness as an opportunity to recover the Sixteen Prefectures, a line of fortified cities and passes that the Liao had annexed from the Shatuo Turk Later Jin in 938, and that the Song had repeatedly but unsuccessfully tried to reconquer.[8] The Song thus sought an alliance with the Jin against their common enemy the Liao.[9]

Because the land routes between the Song and Jin were controlled by the Liao, diplomatic exchanges had to occur by traveling across the Bohai Sea.[10] Negotiations for an alliance began secretly under the pretense that the Song wanted to acquire horses from the Khitans. Song diplomats traveled to the Jin court to meet Aguda in 1118, while Jurchen envoys arrived in the Song capital Kaifeng the next year.[9] At the beginning, the two sides agreed to keep whatever Liao territory they would seize in combat.[9] In 1120, Aguda agreed to cede the Sixteen Prefectures to the Song in exchange for transfer to the Jin of the annual tributary payments that the Song had been giving the Liao.[11] By the end of 1120, however, the Jurchens had seized the Liao Supreme Capital, and offered the Song only parts of the Sixteen Prefectures.[11] Among other things, Jin would keep the Liao Western Capital of Datong at the western end of the Sixteen Prefectures.[11] The two sides agreed that the Jin would now attack the Liao Central Capital, whereas the Song would seize the Liao Southern Capital, Yanjing (modern-day Beijing).

The joint attack against the Liao had been planned for 1121, but it was rescheduled for 1122. On February 23 of that year, Jin captured the Liao Central Capital as promised.[12] The Song delayed their entry into the war because it diverted resources to fighting the Western Xia in the northwest and suppressing a large popular rebellion led by Fang La in the south.[13] When a Song army under Tong Guan's command finally attacked Yanjing in May 1122, the smaller forces of the weakened Liao repelled the invaders with ease.[14] Another attack failed in the fall.[14] Both times, Tong was forced to retreat back to Kaifeng.[15] After the first attack, Aguda changed the terms of the agreement and only promised Yanjing and six other prefectures to the Song.[16] In early 1123 it was Jurchen forces that easily took the Liao Southern Capital. They sacked it and enslaved its population.[16]

The quick collapse of the Liao led to more negotiations between the Song and Jin. Jurchen military success and their effective control over the Sixteen Prefectures gave them more leverage.[16] Aguda grew increasingly frustrated as he realized that despite their military failures the Song still intended to seize most of the prefectures.[17] In the spring of 1123 the two sides finally set the terms of the first Song–Jin treaty.[18] Only seven prefectures (including Yanjing) would be returned to the Song, and the Song would pay an annual indemnity of 300,000 packs of silk and 200,000 taels of silver to the Jin, as well as a one-time payment of one million strings of copper coins to compensate the Jurchens for the tax revenue they would have earned had they not returned the prefectures.[19] In May 1123 Tong Guan and the Song armies entered the looted Yanjing.[16]

War against the Northern Song

Collapse of the Song–Jin alliance

Barely one month after the Song had recovered Yanjing, Zhang Jue (張覺), who had served as military governor of the Liao prefecture of Pingzhou about 200 kilometres (120 mi) east of Yanjing, killed the main Jin official in that city and turned it over to the Song.[20] The Jurchens defeated his armies a few months later and Zhang took refuge in Yanjing. Even though the Song agreed to execute him in late 1123, this incident put tension between the two states, because the 1123 treaty had explicitly forbidden both sides from harboring defectors.[21] In 1124, Song officials further angered Jin by asking for the cession of nine more border prefectures.[21] The new Jin emperor Taizong (r. 1123–1135), Aguda's brother and successor, hesitated, but warrior princes Wanyan Zonghan and Wanyan Zongwang (完颜宗望) vehemently refused to give them any more territory. Taizong eventually granted two prefectures, but by then the Jin leaders were ready to attack their southern neighbor.[22]

Before they could invade the Song, the Jurchens reached a peace agreement with their western neighbors the Tangut Western Xia in 1124. The following year near the Ordos Desert, they captured Tianzuo, the last emperor of the Liao, putting an end to the Liao dynasty for good.[23] Ready to end their alliance with the Song, the Jurchens began preparations for an invasion.[24]

First campaign

In November 1125 Taizong ordered his armies to attack the Song.[23] The defection of Zhang Jue two years earlier served as the casus belli.[21] Two armies were sent to capture the major cities of the Song.[22]

Siege of Taiyuan

The western army, led by Wanyan Zonghan, departed from Datong and headed towards Taiyuan through the mountains of Shanxi, on its way to the Song western capital Luoyang.[25] The Song forces were not expecting an invasion and were caught off guard. The Chinese general Tong Guan was informed of the military expedition by an envoy he had sent to the Jin to obtain the cession of two prefectures. The returning envoy reported that the Jurchens were willing to forgo an invasion if the Song ceded control of Hebei and Shanxi to the Jin.[26] Tong Guan retreated from Taiyuan and left command of his troops to Wang Bing.[27] Jin armies besieged the city in mid January 1126.[28] Under Wang Bing's command, Taiyuan held on long enough to stop the Jurchen troops from advancing to Luoyang.[27]

First siege of Kaifeng

Meanwhile, the eastern army, commanded by Wanyan Zongwang, was dispatched towards Yanjing (modern Beijing) and eventually the Song capital Kaifeng. It did not face much armed opposition. Zongwang easily took Yanjing, where Song general and former Liao governor Guo Yaoshi (郭藥師) switched his allegiances to the Jin.[27] When the Song had tried to reclaim the Sixteen Prefectures, they had faced fierce resistance from the Han Chinese population, yet when the Jurchens invaded that area, the Han Chinese did not oppose them at all.[29] By the end of December 1125, the Jin army had seized control of two prefectures and re-established Jurchen rule over the Sixteen Prefectures.[26] The eastern army was nearing Kaifeng by early 1126.[27]

Fearing the approaching Jin army, Song emperor Huizong planned to retreat south. The emperor deserting the capital would have been viewed as an act of capitulation, so court officials convinced him to abdicate.[27] There were few objections. Rescuing an empire in crisis from destruction was more important than preserving the rituals of imperial inheritance. In January 1126, a few days before the New Year, Huizong abdicated in favor of his son and was demoted to the ceremonial role of Retired Emperor.[30] The Jurchen forces reached the Yellow River on January 27, 1126, two days after the New Year.[23] Huizong fled Kaifeng the next day, escaping south and leaving the newly enthroned emperor Qinzong (r. 1126–1127) in charge of the capital.[23]

Kaifeng was besieged on January 31, 1126.[31] The commander of the Jurchen army promised to spare the city if the Song submitted to Jin as a vassal; forfeited the prime minister and an imperial prince as prisoners; ceded the Chinese prefectures of Hejian, Taiyuan, and Zhongshan; and offered an indemnity of 50 million taels of silver, 5 million taels of gold, 1 million packs of silk, 1 million packs of satin, 10,000 horses, 10,000 mules, 10,000 cattle, and 1,000 camels.[32] This indemnity was worth about 180 years of the annual tribute the Song had been paying to the Jin since 1123.[33]

With little prospect of help from afar arriving, infighting broke out in the Song court between the officials who supported the Jin offer and those who opposed it.[30] Opponents of the treaty like Li Gang (李剛; 1083–1140) rallied around the proposal of remaining in defensive positions until reinforcements arrived and Jurchen supplies ran out. They botched an ambush against the Jin that was carried out at night, and were replaced by officials who supported peace negotiations.[34] The failed attack pushed Qinzong into meeting the Jurchen demands, and his officials convinced him to go through with the deal.[35] The Song recognized Jin control over the three prefectures.[36] The Jurchen army ended the siege in March after 33 days.[31]

Second campaign

Almost as soon as the Jin armies had left Kaifeng, Emperor Qinzong reneged on the deal and dispatched two armies to repel the Jurchen troops attacking Taiyuan and bolster the defenses of Zhongshan and Hejian. An army of 90,000 soldiers and another of 60,000 were defeated by Jin forces by June. A second expedition to rescue Taiyuan was also unsuccessful.[31]

Accusing the Song of violating the agreement and realizing the weakness of the Song, the Jin generals launched a second punitive campaign, again dividing their troops into two armies.[37] Wanyan Zonghan, who had withdrawn from Taiyuan after the Kaifeng agreement and left a small force in charge of the siege, came back with his western army. Overwhelmed, Taiyuan fell in September 1126, after 260 days of siege.[38] When the Song court received news of the fall of Taiyuan, the officials who had advocated defending the empire militarily fell from favor again and were replaced by counselors who favored appeasement.[39] In mid-December the two Jurchen armies converged on Kaifeng for the second time that year.[31]

Second siege of Kaifeng

After the defeat of several Song armies in the north, Emperor Qinzong wanted to negotiate a truce with the Jin, but he committed a massive strategic blunder when he commanded his remaining armies to protect prefectural cities instead of Kaifeng. Neglecting the importance of the capital, he left Kaifeng defended with fewer than 100,000 soldiers. The Song forces were dispersed throughout China, powerless to stop the second Jurchen siege of the city.[31]

The Jin assault commenced in mid-December 1126. Even as fighting raged on, Qinzong continued to sue for peace, but Jin demands for territory were enormous: they wanted all provinces north of the Yellow River.[40] After more than twenty days of heavy combat against the besieging forces, Song defenses were decimated and the morale of Song soldiers was on the decline.[41] On January 9, 1127, the Jurchens broke through and started to loot the conquered city. Emperor Qinzong tried to appease the victors by offering the remaining wealth of the capital. The royal treasury was emptied and the belongings of the city's residents were seized.[42] The Song emperor offered his unconditional surrender a few days later.[43]

On the evening of the twenty-fifth, [Yao] Zhongyou was beaten to death by soldiers in the southern part of the city. His brain and intestines scattered, it was impossible to locate his flesh and bones afterward. Even his home got ransacked. What a shameful end to a good man like him! The spirit of the warrior flowed in Yao’s blood. For three generations, his family served the state loyally and their name was feared among the barbarians. Ever since the defense began, he labored day and night and allowed himself little time to eat and rest. He was the only court official to do this. How ironic that he would meet his tragic end because of it![44]

— Shi Maoliang describing the aftermath of one of the defenders of Bianjing (Kaifeng)

Qigong, the former emperor Huizong, and members of the Song court were captured by the Jurchens as hostages.[33] They were taken north to Huining (modern Harbin), where they were stripped of their royal privileges and reduced to commoners.[45] The former emperors were humiliated by their captors. They were mocked with disparaging titles like "Muddled Virtue" and "Double Muddled". In 1128 Jin made them perform a ritual meant for war criminals.[46] The harsh treatment of the Song royalty softened after the death of Huizong in 1135. Titles were granted to the deceased monarch, and his son Qinzong was promoted to Duke, a position with a salary.[47]

Reasons for Song failure

Many factors contributed to the Song's repeated military blunders and subsequent loss of northern China to the Jurchens. Traditional accounts of Song history held the venality of Huizong's imperial court responsible for the decline of the dynasty.[48] These narratives condemned Huizong and his officials for their moral failures.[49] Early Song emperors were eager to enact political reforms and revive the ethical framework of Confucianism, but the enthusiasm for reforms gradually died after the reformist Wang Anshi's expulsion as chancellor in 1076.[50] Corruption marred the reign of Huizong, who was more skilled as a painter than as a ruler. Huizong was known for his extravagance, and funded the costly construction of gardens and temples while rebellions threatened the state's grip on power.[51]

A modern analysis by Ari Daniel Levine places more of the blame on deficiencies in the military and bureaucratic leadership. The loss of northern China was not inevitable.[48] The military was overextended by a government too assured of its own military prowess. Huizong diverted the state's resources to failed wars against the Western Xia. The Song insistence on a greater share of Liao territory only succeeded in provoking their Jin allies.[52] Song diplomatic oversights underestimated Jin and allowed the unimpeded rise of Jurchen military power.[53] The state had plentiful resources, with the exception of horses, but managed its assets poorly during battles.[54] Unlike the expansive Han and Tang empires that preceded the Song, the Song did not have a significant foothold in Central Asia where a large proportion of its horses could be bred or procured.[55] As Song general Li Gang noted, without a consistent supply of horses the dynasty was at a significant disadvantage against Jurchen cavalry: "Jin were victorious only because they used iron-shielded cavalry, while we opposed them with foot soldiers. It is only to be expected that [our soldiers] were scattered and dispersed."[56]

Wars with the Southern Song

Southern retreat of the Song court

The enthronement of Emperor Gaozong

The Jin leadership had not expected or desired the fall of the Song dynasty. Their intention was to weaken the Song in order to demand more tribute, and they were unprepared for the magnitude of their victory.[57] The Jurchens were preoccupied with strengthening their rule over the areas once controlled by Liao. Instead of continuing their invasion of the Song, an empire with a military that outnumbered their own, they adopted the strategy of "using Chinese to control the Chinese".[58] The Jin hoped a proxy state would be capable of administering northern China and collecting the annual indemnity without requiring Jurchen interventions to quell anti-Jin uprisings.[57] In 1127, the Jurchens installed a former Song official, Zhang Bangchang (張邦昌; 1081–1127), as puppet emperor of the newly established "Da Chu" (Great Chu) dynasty.[59] The puppet government did not deter the resistance in northern China, but the insurgents were motivated by their anger towards the Jurchens' looting rather than by a sense of loyalty towards the inept Song court.[57] A number of Song commanders, stationed in towns scattered across northern China, retained their allegiance to the Song, and armed volunteers organized militias opposed to the Jurchen military presence. The insurgency hampered the ability of the Jin to exert control over the north.[60]

Meanwhile, one Song prince, Zhao Gou, had escaped capture.[61] He had been held up in Cizhou while on a diplomatic mission, and never made it back to Kaifeng. He was not present in the capital when the city fell to the Jurchens.[62] The future Emperor Gaozong managed to evade the Jurchen troops tailing him by moving from one province to the next, traveling across Hebei, Henan, and Shandong. The Jurchens tried to lure him back to Kaifeng where they could finally capture him, but did not succeed.[63] Zhao Gou finally arrived in the Song Southern Capital at Yingtianfu (應天府; modern Shangqiu) in early June 1127.[62] For Gaozong (r. 1127–1162), Yingtianfu was the first in a series of temporary capitals called xingzai 行在.[64] The court moved to Yingtianfu because of its historical importance to Emperor Taizu of Song, the founder of the dynasty, who had previously served in that city as a military governor. The symbolism of the city was meant to secure the political legitimacy of the new emperor, who was enthroned there on June 12.[65]

After reigning for barely one month, Zhang Bangchang was persuaded by the Song to step down as emperor of the Great Chu and to recognize the legitimacy of the Song imperial line.[62] Li Gang pressured Gaozong to execute Zhang for betraying the Song.[66] The emperor relented and Zhang was coerced into suicide.[59] The killing of Zhang showed that the Song was willing to provoke the Jin, and that the Jin had yet to solidify their control over the newly conquered territories.[67] The submission and abolition of Chu meant that Kaifeng was now back under Song control. Zong Ze (宗澤; 1059–1128), the Song general responsible for fortifying Kaifeng, entreated Gaozong to move the court back to the city, but Gaozong refused and retreated south.[68] The southward move marked the end of the Northern Song and the beginning of the Southern Song era of Chinese history.[1]

The descendant of Confucius at Qufu, the Duke Yansheng Kong Duanyou fled south with the Song Emperor to Quzhou, while the newly established Jin dynasty (1115–1234) in the north appointed Kong Duanyou's brother Kong Duancao who remained in Qufu as Duke Yansheng.[69] Zhang Xuan 張選, a great-grandson of Zhang Zai, also fled south with Gaozong.

The move south

The Song disbandment of the Great Chu and execution of Zhang Bangchang antagonized the Jurchens and violated the treaty that the two parties had negotiated. The Jin renewed their attacks on the Song and quickly reconquered much of northern China.[66] In late 1127 Gaozong moved his court further south from Yingtianfu to Yangzhou, south of the Huai River and north of the Yangtze River, by sailing down the Grand Canal.[70] The court spent over a year in the city.[71] When the Jurchens advanced to the Huai River, the court was partially evacuated to Hangzhou in 1129.[68] Days later, Gaozong narrowly escaped on horseback, just a few hours ahead of Jurchen vanguard troops.[71] After a coup in Hangzhou almost dethroned him, in May 1129 he moved his capital back north to Jiankang (modern Nanjing) on the south bank of the Yangtze.[72] One month later, however, Zong Ze's successor Du Chong (杜充) vacated his forces from Kaifeng, exposing Jiankang to attack. The emperor moved back to Hangzhou in September, leaving Jiankang in Du Chong's hands.[73] The Jin eventually captured Kaifeng in early 1130.[74]

From 1127 to 1129, the Song sent thirteen embassies to the Jin to discuss peace terms and to negotiate the release of Gaozong's mother and Huizong, but the Jin court ignored them.[75] In December 1129, the Jin started a new military offensive, dispatching two armies across the Huai River in the east and west. On the western front, an army invaded Jiangxi, the area where the Song dowager empress resided, and captured Hongzhou (洪州, present-day Nanchang).[73] They were ordered to retreat a few months later when the eastern army withdrew.[74]

Meanwhile, on the eastern front, Wuzhu commanded the main Jin army. He crossed the Yangtze southwest of Jiankang and took that city when Du Chong surrendered.[73] Wuzhu set out from Jiankang and advanced rapidly to try to capture Gaozong.[76] The Jin seized Hangzhou (January 22, 1130) and then Shaoxing further south (February 4), but general Zhang Jun's (1086–1154) battle with Wuzhu near Ningbo gave Gaozong time to escape.[77] By the time Wuzhu resumed pursuit, the Song court was fleeing on ships to islands off the coast of Zhejiang, and then further south to Wenzhou.[76] The Jin sent ships to chase after Gaozong, but failed to catch him. They gave up the pursuit and the Jurchens retreated north.[77] After they plundered the undefended cities of Hangzhou and Suzhou, they finally started to face resistance from Song armies led by Yue Fei and Han Shizhong.[77] The latter even inflicted a major defeat on Jurchen forces and tried to prevent Wuzhu from crossing back to the north bank of the Yangtze. The small boats of the Jin army were outmatched by Han Shizhong's fleet of seagoing vessels. Wuzhu eventually managed to cross the river when he had his troops use incendiary arrows to neutralize Han's ships by burning their sails. Wuzhu's troops came back south of the Yangtze one last time to Jiankang, which they pillaged, and then headed north. Yet the Jin had been caught off guard by the strength of the Song navy, and Wuzhu never tried to cross the Yangtze River again.[77] In early 1131, Jin armies between the Huai and the Yangtze were repelled by bandits loyal to the Song. Zhang Rong (張榮), the leader of the bandits, was given a government position for his victory against the Jin.[74]

After the Jin incursion that almost captured Gaozong, the sovereign ordered pacification commissioner Zhang Jun (1097–1164), who was in charge of Shaanxi and Sichuan in the far west, to attack the Jin there to relieve pressure on the court. Zhang put together a large army, but was defeated by Wuzhu near Xi'an in late 1130. Wuzhu advanced further west into Gansu, and drove as far south as Jiezhou (階州, modern Wudu).[78] The most important battles between Jin and Song in 1131 and 1132 took place in Shaanxi, Gansu, and Sichuan. The Jin lost two battles at Heshang Yuan in 1131. After failing to enter Sichuan, Wuzhu retreated to Yanjing. He returned to the western front again from 1132 to 1134. The Jin attacked Hubei and Shaanxi in 1132. Wuzhu captured Heshang Yuan in 1133, but his advance was halted by a defeat at Xianren Pass. He gave up on taking Sichuan, and no more major battles were fought between the Jin and Song for the rest of the decade.[78]

The Song court returned to Hangzhou in 1133, and the city was renamed Lin'an.[79] The imperial ancestral temple was built in Lin'an later that same year, a sign that the court had in practice established Lin'an as the Song capital without a formal declaration.[80] It was treated as a temporary capital.[81] Between 1130 and 1137, the court would sporadically move to Jiankang, and back to Lin'an. There were proposals to make Jiankang the new capital, but Lin'an won out because the court considered it a more secure city.[82] The natural barriers that surrounded Lin'an, including lakes and rice paddies, made it more difficult for the Jurchen cavalry to breach its fortifications.[83] Access to the sea made it easier to retreat from the city.[84] In 1138, Gaozong officially declared Lin'an the capital of the dynasty, but the label of temporary capital would still be in place.[85] Lin'an would remain the capital of the Southern Song for the next 150 years, growing into a major commercial and cultural center.[86]

Da Qi invades the Song

Qin Hui, an official of the Song court, recommended a peaceful solution to the conflict in 1130, saying that, "If it is desirable that there will be no more conflicts under Heaven, it is necessary for the southerners to stay in the south and the northerners in the north."[87] Gaozong, who considered himself a northerner, initially rejected the proposal. There were gestures toward peace in 1132, when the Jin freed an imprisoned Song diplomat, and in 1133, when the Song offered to become a Jin vassal, but a treaty never materialized.[88] The Jin requirement that the border between the two states be moved south from the Huai River to the Yangtze was too large of a hurdle for the two sides to reach an agreement.[89]

The continuing insurgency of anti-Jin forces in northern China hampered the Jurchen campaigns south of the Yangtze. Reluctant to let the war drag on, the Jin decided to create Da Qi (the "Great Qi"), their second attempt at a puppet state in northern China.[60] The Jurchens believed that this state, nominally ruled by someone of Han Chinese descent, would be able to attract the allegiance of disaffected members of the insurgency. The Jurchens also suffered from a shortage of skilled manpower, and controlling the entirety of northern China was not administratively feasible.[60] In the final months of 1129, Liu Yu (劉豫; 1073–1143) won the favor of the Jin emperor Taizong.[60] Liu was a Song official from Hebei who had been a prefect of Jinan in Shandong before his defection to the Jin in 1128.[60] Da Qi was formed late in 1130, and the Jin enthroned Liu as its emperor.[74] Daming in Hebei was the first capital of Qi, before its move to Kaifeng, former capital of the Northern Song.[90] The Qi government instituted military conscription, made an attempt at reforming the bureaucracy, and enacted laws that enforced the collection of high taxes.[46] It was also responsible for supplying a large portion of the troops that fought the Song in the seven years following its creation.[75]

The Jin granted Qi more autonomy than the first puppet government of Chu, but Liu Yu was obligated to obey the orders of the Jurchen generals.[75] With Jin support, Da Qi invaded the Song in November 1133. Li Cheng, a Song turncoat who had joined the Qi, led the campaign. Xiangyang and nearby prefectures fell to his army. The capture of Xiangyang on the Han River gave the Jurchens a passage into the central valley of the Yangtze River.[89] Their southward push was halted by the general Yue Fei.[46] In 1134, Yue Fei defeated Li and retook Xiangyang and its surrounding prefectures. Later that year, however, Qi and Jin initiated a new offensive further east along the Huai River. For the first time, Gaozong issued an edict officially condemning Da Qi.[89] The armies of Qi and Jin won a series of victories in the Huai valley, but were repelled by Han Shizhong near Yangzhou and by Yue Fei at Luzhou (廬州, modern Hefei).[91] Their sudden withdrawal in 1135 in response to the death of Jin Emperor Taizong gave the Song time to regroup.[91] The war recommenced in late 1136 when Da Qi attacked the Huainan circuits of the Song. Qi lost a battle at Outang (藕塘), in modern Anhui, against a Song army led by Yang Qizhong (楊沂中; 1102–1166). The victory boosted Song morale, and the military commissioner Zhang Jun (1097–1164) convinced Gaozong to begin plans for a counterattack. Gaozong first agreed, but he abandoned the counteroffensive when an officer named Li Qiong (酈瓊) killed his superior official and defected to the Jin with 30,000 soldiers.[92][93] This rebellion was provoked by Zhang Jun's attempt to reassert government control over the regional military commanders, as the court had previously been forced to tolerate growing military autonomy during the chaos of the Jin invasion.[94] Meanwhile, Emperor Xizong (r. 1135–1150) inherited the Jin throne from Taizong, and pushed for peace.[95] He and his generals were disappointed with Liu Yu's military failures and believed that Liu was secretly conspiring with Yue Fei.[95] In late 1137, the Jin reduced Liu Yu's title to that of a prince and abolished the state of Qi.[46] The Jin and Song renewed the negotiations towards peace.[95]

Song counteroffensive and the peace process

Gaozong promoted Qin Hui in 1138 and put him in charge of deliberations with the Jin.[95] Yue Fei, Han Shizhong, and a large number of officials at court criticized the peace overtures.[96] Aided by his control of the Censorate, Qin purged his enemies and continued negotiations. In 1138 the Jin and Song agreed to a treaty that designated the Yellow River as border between the two states and recognized Gaozong as a "subject" of the Jin. But because there remained opposition to the treaty in both the courts of the Jin and Song, the treaty never came into effect.[97] A Jurchen army led by Wuzhu invaded in early 1140.[97] The Song counteroffensive that followed achieved large territorial gains.[98] Song general Liu Qi (劉錡) won a battle against Wuzhu at Shunchang (modern Fuyang in Anhui).[97] Yue Fei was assigned to head the Song forces defending the Huainan region. Instead of advancing to Huainan, however, Wuzhu retreated to Kaifeng and Yue's army followed him into Jin territory, disobeying an order by Gaozong that forbade Yue from going on the offensive. Yue captured Zhengzhou and sent soldiers across the Yellow River to stir up a peasant rebellion against the Jin. On July 8, 1140, at the Battle of Yancheng, Wuzhu launched a surprise attack on Song forces with an army of 100,000 infantry and 15,000 horsemen. Yue Fei directed his cavalry to attack the Jurchen soldiers and won a decisive victory. He continued on to Henan, where he recaptured Zhengzhou and Luoyang. Later in 1140, Yue was forced to withdraw after the emperor ordered him to return to the Song court.[99]

Emperor Gaozong supported settling a peace treaty with the Jurchens and sought to rein in the assertiveness of the military. The military expeditions of Yue Fei and other generals were an obstacle to peace negotiations.[100] The government weakened the military by rewarding Yue Fei, Han Shizhong, and Zhang Jun (1086–1154) with titles that relieved them of their command over the Song armies.[97] Han Shizhong, a critic of the treaty, retired.[101] Yue Fei also announced his resignation as an act of protest.[100] In 1141 Qin Hui had him imprisoned for insubordination. Charged with treason, Yue Fei was poisoned in jail on Qin's orders in early 1142. Jurchen diplomatic pressure during the peace talks may have played a role, but Qin Hui's alleged collusion with the Jin has never been proven.[102]

After his execution, Yue Fei's reputation for defending the Southern Song grew to that of a national folk hero.[103] Qin Hui was denigrated by later historians, who accused him of betraying the Song.[104] The real Yue Fei differed from the later myths based on his exploits.[105] Contrary to traditional legends, Yue was only one of many generals who fought against the Jin in northern China.[106] Traditional accounts have also blamed Gaozong for Yue Fei's execution and submitting to the Jin.[107] Qin Hui, in a reply to Gaozong's gratitude for the success of the peace negotiations, told the emperor that "the decision to make peace was entirely Your Majesty's. Your servant only carried it out; what achievement was there in this for me?"[108]

Treaty of Shaoxing

On October 11, 1142, after about a year of negotiations, the Treaty of Shaoxing was ratified, ending the conflict between the Jin and the Song.[109] By the terms of the treaty, the Huai River, north of the Yangtze, was designated as the boundary between the two states. The Song agreed to pay a yearly tribute of 250,000 taels of silver and 250,000 packs of silk to the Jin.[110]

The treaty reduced the Southern Song dynasty status to that of a Jin vassal. The document designated the Song as the "insignificant state", while the Jin was recognized as the "superior state". The text of the treaty has not survived in Chinese records, a clear sign of its humiliating reputation. The contents of the agreement were recovered from a Jurchen biography. Once the treaty had been settled, the Jurchens retreated north and trade resumed between the two empires.[111] The peace ensured by the Treaty of Shaoxing lasted for the next 70 years, but was interrupted twice. One military campaign was initiated by the Song and the other by the Jin.[112]

Further campaigns

Wanyan Liang's war

Wanyan Liang led a coup against Emperor Xizong and became fourth emperor of the Jin dynasty in 1150.[113] Wanyan Liang presented himself as a Chinese emperor, and planned to unite China by conquering the Song. In 1158, Wanyan Liang provided a casus belli by announcing that the Song had broken the 1142 peace treaty by acquiring horses.[114] He instituted an unpopular draft that was the source of widespread unrest in the empire. Anti-Jin revolts erupted among the Khitans and in Jin provinces bordering the Song. Wanyan Liang did not allow dissent, and opposition to the war was severely punished.[115] The Song had been notified beforehand of Wanyan Liang's plan. They prepared by securing their defenses along the border, mainly near the Yangtze River, but were hampered by Emperor Gaozong's indecisiveness.[116] Gaozong's desire for peace made him averse to provoking the Jin.[117] Wanyan Liang began the invasion in 1161 without formally declaring war.[118] Jurchen armies personally led by Wanyan Liang left Kaifeng on October 15, reached the Huai River border on October 28, and marched in the direction of the Yangtze. The Song lost the Huai to the Jurchens but captured a few Jin prefectures in the west, slowing the Jurchen advance.[118] A group of Jurchen generals were sent to cross the Yangtze near the city of Caishi (south of Ma'anshan in modern Anhui) while Wanyan Liang established a base near Yangzhou.[119]

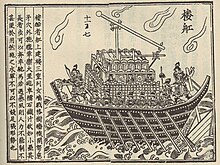

The Song official Yu Yunwen was in command of the army defending the river.[120] The Jurchen army was defeated while attacking Caishi between November 26 and 27 during the Battle of Caishi.[119] The paddle-wheel ships of the Song navy, armed with trebuchets that fired gunpowder bombs, overwhelmed the light ships of the Jin fleet.[121] Jin ships were unable to compete because they were smaller and hastily constructed.[120] The bombs launched by the Song contained mixtures of gunpowder, lime, scraps of iron, and a poison that was likely arsenic.[122] Traditional Chinese accounts consider this the turning point of the war, characterizing it as a military upset that secured southern China from the northern invaders. The significance of the battle is said to have rivaled a similarly revered victory at the Battle of Fei River in the 4th century. Contemporaneous Song accounts claimed that the 18,000 Song soldiers commanded by Yu Yunwen and tasked with defending Caishi were able to defeat the invading Jurchen army of 400,000 soldiers. Modern historians are more skeptical and consider the Jurchen numbers an exaggeration. Song historians may have confused the number of Jurchen soldiers at the Battle of Caishi with the total number of soldiers under the command of Wanyan Liang. The conflict was not the one-sided battle that traditional accounts imply, and the Song had numerous advantages over the Jin. The Song fleet was larger than the Jin's, and the Jin were unable to use their greatest asset, cavalry, in a naval battle.[119]

Government troops using the “sea-eels” sailed straight towards the seventeen [enemy] boats, and split them up into two groups. The government troops shouted “The government troops have won,” and struck at the men of Jin. The bottoms of the boats of the Jin were as broad as a box and the boats were unstable. Moreover, their men knew nothing about handling boats and were quite helpless. Only five or seven men [on each boat] could use their bows. So they were all killed in the river.[123]

— Zhao Shengzhi, writing after the death of Yu Yunwen, describing the battle at Caishi as a relatively minor battle involving only a few vessels

A modern analysis of the battlefield has shown that it was a minor battle, although the victory did boost Song morale. The Jin lost, but only suffered about 4,000 casualties and the battle was not fatal to the Jurchen war effort.[119] It was Wanyan Liang's poor relationships with the Jurchen generals, who despised him, that doomed the chances of a Jin victory. On December 15, Wanyan Liang was assassinated in his military camp by disaffected officers. He was succeeded by Emperor Shizong (r. 1161–1189), who had long resented Digunai for driving his wife, Lady Wulinda, to suicide.[124] Shizong was pressured into ending the unpopular war with the Song, and ordered the withdrawal of Jin forces in 1162.[125] Emperor Gaozong retired from the throne that same year. His mishandling of the war with Wanyan Liang was one of many reasons for his abdication.[126] Skirmishes between the Song and Jin continued along the border, but subsided in 1165 after the negotiation of a peace treaty. There were no major territorial changes. The treaty dictated that the Song still had to pay the annual indemnity, but the indemnity was renamed from "tribute", which had implied a subordinate relationship, to "payment".[127]

Song revanchism

The Jin were weakened by the pressure of the rising Mongols to the north, a series of floods culminating in a Yellow River flood in 1194 that devastated Hebei and Shandong in northern China, and the droughts and swarming locusts that plagued the south near the Huai.[128] The Song were informed of the Jurchen predicament by their ambassadors, who traveled twice a year to the Jin capital, and started provoking their northern neighbor. The hostilities were instigated by chancellor Han Tuozhou.[129] The Song Emperor Ningzong (r. 1194–1224) took little interest in the war effort.[130] Under Han Tuozhou's supervision, preparations for the war proceeded gradually and cautiously.[131] The court venerated the irredentist hero Yue Fei and Han orchestrated the publishing of historical records that justified war with the Jin.[131] From 1204 onwards, Chinese armed groups raided Jurchen settlements.[129] Han Tuozhou was designated the head of national security in 1205. The Song funded insurgents in the north that professed loyalist sympathies.[131] These early clashes continued to escalate, partly abetted by revanchist Song officials, and war against the Jin was officially declared on June 14, 1206.[129] The document that announced the war claimed the Jin lost the Mandate of Heaven, a sign that they were unfit to rule, and called for an insurrection of Han Chinese against the Jin state.[132]

Song armies led by general Bi Zaiyu (畢再遇; d. 1217) captured the barely defended border city of Sizhou 泗州 (on the north bank of the Huai River across from modern Xuyi County) but suffered large losses against the Jurchens in Hebei.[133] The Jin repelled the Song and moved south to besiege the Song town of Chuzhou 楚州 on the Grand Canal just south of the Huai River. Bi defended the town, and the Jurchens withdrew from the siege after three months.[134] By the fall of 1206, however, the Jurchens had captured multiple towns and military bases.[135] The Jin initiated an offensive against Song prefectures in the central front of the war, capturing Zaoyang and Guanghua (光化; on the Han River near modern Laohekou).[136] By the fall of 1206, the Song offensive had already failed disastrously.[137] Soldier morale sank as weather conditions worsened, supplies ran out, and hunger spread, forcing many to desert. The massive defections of Han Chinese in northern China that the Song had expected never materialized.[135]

A notable betrayal did occur on the Song side, however: Wu Xi (吳曦; d. 1207), the governor-general of Sichuan, defected to the Jin in December 1206.[135] The Song had depended on Wu's success in the west to divert Jin soldiers away from the eastern front.[138] He had attacked Jin positions earlier in 1206, but his army of about 50,000 men had been repelled.[139] Wu's defection could have meant the loss of the entire western front of the war, but Song loyalists assassinated Wu on March 29, 1207, before Jin troops could take control of the surrendered territories.[140] An Bing (安丙; d. 1221) was given Wu Xi's position, but the cohesion of Song forces in the west fell apart after Wu's demise and commanders turned on each other in the ensuing infighting.[141]

Fighting continued in 1207, but by the end of that year the war was at a stalemate. The Song was now on the defensive, while the Jin failed to make gains in Song territory it therefore cost both parties much more than it gained them.[137] The failure of Han Tuozhou's aggressive policies against the Jurchens by this time round had depopularised him amongst the common people which situation was exploited by the Empress Yang and Shi Miyuan, his most powerful political rivals to Garner support amongst other Courtiers which led to his demise. On November 24, 1207, Han Touzhou on his way to Court he was intercepted, dragged outside Imperial precincts and bludgeoned to death by the Imperial Palace Guards. His accomplice Su Shidan (蘇師旦) was executed, and other officials connected to Han were dismissed or exiled.[142] Since neither combatant was eager to continue the war, they returned to negotiations. A peace treaty was signed on November 2, 1208, and the Song tribute to the Jin was reinstated. The Song annual indemnity increased by 50,000 taels of silver and 50,000 packs of fabric.[143] The treaty also stipulated that the Song had to present to the Jin the head of Han Tuozhou, who the Jin held responsible for starting the war.[143] The heads of Han and Su were severed from their exhumed corpses, exhibited to the public, then delivered to the Jin.[144]

Jin–Song war during the rise of the Mongols

The Mongols, a nomadic confederation, had unified in the middle of the twelfth century. They and other steppe nomads occasionally raided the Jin empire from the northwest. The Jin shied away from punitive expeditions and was content with appeasement, similar to the practices of the Song.[112] The Mongols, formerly a Jin tributary, ended their Jurchen vassalage in 1210 and attacked the Jin in 1211.[145] In light of this event, the Song court debated ending tributary payments to the weakened Jin, but they again chose to avoid antagonizing the Jin.[146] They refused Western Xia's offers of allying against the Jin in 1214 and willingly complied when in 1215 the Jin rejected a request to lower the annual indemnity.[147] Meanwhile, in 1214, the Jin retreated from the besieged capital of Zhongdu to Kaifeng, which became the new capital of the dynasty.[148] As the Mongols expanded, the Jin suffered territorial losses and attacked the Song in 1217 to compensate for their shrinking territory.[149] Periodic Song raids against the Jin were the official justification for the war. Another likely motive was that the conquest of the Song would have given the Jin a place to escape should the Mongols succeed in taking control of the north.[150] Shi Miyuan (史彌遠; 1164–1233), the chancellor of Song Emperor Lizong (r. 1224–1264), was hesitant to fight the Jin and delayed the declaration of war for two months. Song generals were largely autonomous, allowing Shi to evade blame for their military blunders.[150] The Jin advanced across the border from the center and western fronts.[150] Jurchen military successes were limited, and the Jin faced repeated raids from the neighboring state of Western Xia.[149] In 1217, the Song generals Meng Zongzheng (孟宗政) and Hu Zaixing (扈再興) defeated the Jin and prevented them from capturing Zaoyang and Suizhou.[151]

A second Jin campaign in late 1217 did marginally better than the first.[152] In the east, the Jin made little headway in the Huai River valley, but in the west they captured Xihezhou and Dasan Pass (大散關; modern Shaanxi) in late 1217.[153] The Jin tried to captured Suizhou in Jingxi South circuit again in 1218 and 1219, but failed.[154] A Song counteroffensive in early 1218 captured Sizhou and in 1219 the Jin cities of Dengzhou and Tangzhou were pillaged twice by a Song army commanded by Zhao Fang (趙方; d. 1221).[155] In the west, command of the Song forces in Sichuan was given to An Bing, who had previously been dismissed from this position. He successfully defended the western front, but was unable to advance further because of local uprisings in the area.[156] The Jin tried to extort an indemnity from the Song but never received it.[149] In the last of the three campaigns, in early 1221, the Jin captured the city of Qizhou (蘄州; in Huainan West) deep in Song territory. Song armies led by Hu Zaixing and Li Quan (李全; d. 1231) defeated the Jin, who then withdrew.[157] In 1224 both sides agreed on a peace treaty that ended the annual tributes to the Jin. Diplomatic missions between the Jin and Song were also cut off.[158]

Mongol–Song alliance

In February 1233, the Mongols took Kaifeng after a siege of more than 10 months and the Jin court retreated to the town of Caizhou.[159] In 1233 Emperor Aizong (r. 1224–1234) of the Jin dispatched diplomats to implore the Song for supplies. Jin envoys reported to the Song that the Mongols would invade the Song after they were done with the Jin—a forecast that would later be proven true—but the Song ignored the warning and rebuffed the request.[160] They instead formed an alliance with the Mongols against the Jin.[159] The Song provided supplies to the Mongols in return for parts of Henan.[159] The Jin dynasty collapsed when Mongol and Song troops defeated the Jurchens at the siege of Caizhou in 1234.[161] General Meng Gong (孟珙) led the Song army against Caizhou.[159] The penultimate emperor of the Jin, Emperor Aizong, took his own life.[162] His short-lived successor, Emperor Mo, was killed in the town a few days later.[160] The Mongols later turned their sights towards the Song. After decades of war, the Song dynasty also fell in 1279, when the remaining Song loyalists lost to the Mongols in a naval battle near Guangdong.[163]

Historical significance

Cultural and demographic changes

Jurchen migrants from the northeastern reaches of Jin territory settled in the Jin-controlled lands of northern China. Constituting less than ten percent of the total population, the two to three million ruling Jurchens were a minority in a region that was still dominated by 30 million Han Chinese.[1] The southward expansion of the Jurchens caused the Jin to transition their decentralized government of semi-agrarian tribes to a bureaucratic Chinese-style dynasty.[112]

The Jin government initially promoted an independent Jurchen culture alongside their adoption of the centralized Chinese imperial bureaucracy, but the empire was gradually sinicized over time. The Jurchens became fluent in the Chinese language, and the philosophy of Confucianism was used to legitimize the ruling government.[1] Confucian state rituals were adopted during the reign of Emperor Xizong (1135–1150).[164] The Jin implemented imperial exams on the Confucian Classics, first regionally and then for the entire empire.[165] The Classics and other works of Chinese literature were translated into Jurchen and studied by Jin intellectuals, but very few Jurchens actively contributed to the classical literature of the Jin.[166] The Khitan script, from the Chinese family of scripts, formed the basis of a national writing system for the empire, the Jurchen script. All three scripts were working languages of the government.[167] Jurchen clans adopted Chinese personal names with their Jurchen names.[168] Wanyan Liang (Prince of Hailing; r. 1150–1161) was an enthusiastic proponent of Jurchen sinicization and enacted policies to encourage it. Wanyan Liang had been acculturated by Song diplomats from childhood, and his emulation of Song practices earned him the Jurchen nickname of "aping the Chinese". He studied the Chinese classics, drank tea, and played Chinese chess for recreation. Under his reign, the administrative core of the Jin state was moved south from Huining. He instated Beijing as the Jin main capital in 1153. Palaces were erected in Beijing and Kaifeng, while the original, more northerly residences of Jurchen chieftains were demolished.[169]

The emperor's political reforms were connected with his desire to conquer all of China and to legitimize himself as a Chinese emperor.[114] The prospect of conquering southern China was cut short by Wanyan Liang's assassination.[125] Wanyan Liang's successor, Emperor Shizong, was less enthusiastic about sinicization and reversed several of Wanyan Liang's edicts. He sanctioned new policies with the intent to slow the assimilation of the Jurchens.[127] Shizong's prohibitions were abandoned by Emperor Zhangzong (r. 1189–1208), who promoted reforms that transformed the political structure of the dynasty closer to that of the Song and Tang dynasties.[170] Despite cultural and demographic changes, military hostilities between the Jin and the Song persisted until the fall of the Jin.[1]

In the south, the retreat of the Song dynasty led to major demographic changes. The population of refugees from the north that resettled in Lin'an and Jiankang (modern Hangzhou and Nanjing) eventually grew greater than the population of original residents, whose numbers had dwindled from repeated Jurchen raids.[171] The government encouraged the resettlement of peasant migrants from the southern provinces of the Song to the underpopulated territories between the Yangtze and the Huai rivers.[171]

The new capital Lin'an grew into a major commercial and cultural center. It rose from a middling city of no special importance to one of the world's largest and most prosperous. During his stay in Lin'an in the Yuan dynasty (1260–1368), when the city was not as wealthy as it had been under the Song, Marco Polo remarked that "this city is greater than any in the world".[172] Once retaking northern China became less plausible and Lin'an grew into a significant trading city, the government buildings were extended and renovated to better befit its status as an imperial capital. The modestly sized imperial palace was expanded in 1133 with new roofed alleyways and in 1148 with an extension of the palace walls.[173]

The loss of northern China, the cultural center of Chinese civilization, diminished the regional status of the Song dynasty. After the Jurchen conquest of the north, Korea recognized the Jin, not the Song, as the legitimate dynasty of China. The Song's military failures reduced it to a subordinate of the Jin, turning it into a "China among equals".[174] The Song economy, however, recovered quickly after the move south. Government revenues earned from taxing foreign trade nearly doubled between the closing of the Northern Song era in 1127 and the final years of Gaozong's reign in the early 1160s.[175] The recovery was not uniform, and areas like Huainan and Hubei that had been directly affected by the war took decades to return to their pre-war levels.[176] In spite of multiple wars, the Jin remained one of the main trading partners of the Song. Song demand for foreign products like fur and horses went unabated. Historian Shiba Yoshinobu (斯波義信, b. 1930) believes that Song commerce with the north was profitable enough that it compensated for the silver delivered annually as an indemnity to the Jin.[177]

The Jin–Song Wars were one of several wars in northern China along with the Uprising of the Five Barbarians, An Lushan Rebellion, Huang Chao Rebellion and the wars of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms which caused a mass migration of Han Chinese from northern China to southern China called "衣冠南渡" (pinyin: yì guān nán dù).[178][179][180][181][182] In 1126–1127 over half a million fled from northern China to southern China including Li Qingzhao.[183][184] One section of the Confucius family led by Duke Yansheng Kong Duanyou moved south to Quzhou with Southern Song emperor Gaozong while his brother Kong Duancao remained behind in Qufu and became the Duke Yansheng for the Jin dynasty. A section of the Zengzi family also moved south with the Southern Song while the other part of the Zengzi family stayed in the north.

However, there was also a reverse migration when the war was over of Han Chinese from the Southern Song towards Jin ruled northern China leading southern China's population to shrink and northern China's population to grow.[185]

Gunpowder warfare

The battles between the Song and the Jin spurred the invention and use of gunpowder weapons. There are reports that the fire lance, one of the earliest ancestors of the firearm, was used by the Song against the Jurchens besieging De'an (德安; modern Anlu in eastern Hubei) in 1132, during the Jin invasion of Hubei and Shaanxi.[187] The weapon consisted of a spear attached with a flamethrower capable of firing projectiles from a barrel constructed of bamboo or paper.[188] They were built by soldiers under the command of Chen Gui (陳規), who led the Song army defending De'an.[189] The fire lances with which Song soldiers were equipped at De'an were built for destroying the wooden siege engines of the Jin and not for combat against the Jin infantry.[190] Song soldiers compensated for the limited range and mobility of the weapon by timing their attacks on the Jin siege engines, waiting until they were within range of the fire lances.[191] Later fire lances used metal barrels, fired projectiles farther and with greater force, and could be used against infantry.[188]

Early rudimentary bombs like the huopao fire bomb (火礮) and the huopao (火砲) bombs propelled by trebuchet were also in use as incendiary weapons. The defending Song army used huopao (火礮) during the first Jin siege of Kaifeng in 1126.[192] On the opposing side, the Jin launched incendiary bombs from siege towers down onto the city below.[193] In 1127, huopao (火礮) were employed by the Song troops defending De'an and by the Jin soldiers besieging the city. The government official Lin Zhiping (林之平) proposed to make incendiary bombs and arrows mandatory for all warships in the Song navy. At the battle of Caishi in 1161, Song ships fired pili huoqiu (霹靂火球), also called pili huopao bombs (霹靂火砲), from trebuchets against the ships of the Jin fleet commanded by Wanyan Liang.[194] The gunpowder mixture of the bomb contained powdered lime, which produced blinding smoke once the casing of the bomb shattered.[195] The Song also deployed incendiary weapons at the battle of Tangdao during the same year.[196]

Gunpowder was also applied to arrows in 1206 by a Song army stationed in Xiangyang. The arrows were most likely an incendiary weapon, but its function may also have resembled that of an early rocket.[197] At the Jin siege of Qizhou (蘄州) in 1221, the Jurchens fought the Song with gunpowder bombs and arrows. The Jin tiehuopao (鐵火砲, "iron huopao"), which had cast iron casings, are the first known hard casing bombs. The bomb needed to be capable of detonating in order to penetrate the iron casing. The Song army had a large supply of incendiary bombs, but there are no reports of them having a weapon similar to the Jin's detonating bombs.[198] A participant in the siege recounted in the Xinsi Qi Qi Lu (辛巳泣蘄錄) that the Song army at Qizhou had an arsenal of 3000 huopao (火礮), 7000 incendiary gunpowder arrows for crossbows and 10000 for bows, as well as 20000 pidapao (皮大礮), probably leather bags filled with gunpowder.[198]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e Holcombe 2011, p. 129.

- ^ Ebrey 2010, p. 136.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 116.

- ^ Tillman, Hoyt Cleveland (1995). Tillman, Hoyt Cleveland; West, Stephen H. (eds.). China Under Jurchen Rule: Essays on Chin Intellectual and Cultural History (illustrated ed.). SUNY Press. p. 27. ISBN 0791422739.

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (2014). Emperor Huizong (illustrated, reprint ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 468. ISBN 978-0674726420.

- ^ Haywood, John; Jotischky, Andrew; McGlynn, Sean (1998). Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600–1492. Barnes & Noble. p. 3.21. ISBN 978-0-7607-1976-3.

- ^ Franke 1994, p. 221.

- ^ Mote 1999, pp. 64–65, 195, and 208.

- ^ a b c Levine 2009, p. 628.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 208.

- ^ a b c Levine 2009, p. 629.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 209.

- ^ Levine 2009, pp. 628–630; Mote 1999, p. 209.

- ^ a b Levine 2009, p. 630.

- ^ Twitchett & Tietze 1994, p. 149.

- ^ a b c d Levine 2009, p. 632.

- ^ Mote 1999, pp. 209–210; Levine 2009, p. 632.

- ^ Mote 1999, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Franke 1994, p. 225; Levine 2009, p. 632.

- ^ Levine 2009, p. 633; Franke 1994, p. 227; Tan 1982, pp. 10–11 (location).

- ^ a b c Levine 2009, p. 633.

- ^ a b Levine 2009, p. 634.

- ^ a b c d Mote 1999, p. 196.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 210.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 196; Levine 2009, p. 636.

- ^ a b Lorge 2005, p. 52.

- ^ a b c d e Levine 2009, p. 636.

- ^ Lorge 2005; Levine 2009, p. 636.

- ^ Franke & Twitchett 1994, p. 39.

- ^ a b Levine 2009, p. 637.

- ^ a b c d e Lorge 2005, p. 53.

- ^ Lorge 2005, pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b Franke 1994, p. 229.

- ^ Levine 2009, p. 638.

- ^ Lorge 2005, p. 53 (failed attack); Levine 2009, p. 639 (officials).

- ^ Levine 2009, p. 639.

- ^ Levine 2009, p. 640; Franke 1994, p. 229.

- ^ Levine 2009, p. 640.

- ^ Levine 2009, p. 641.

- ^ Levine 2009, pp. 641–642.

- ^ Lorge 2005, p. 53; Levine 2009, p. 642.

- ^ Lorge 2005, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Franke 1994, p. 229; Levine 2009, p. 642.

- ^ Yue 2020, p. 44.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 197.

- ^ a b c d Franke 1994, p. 232.

- ^ Franke 1994, pp. 232–233.

- ^ a b Levine 2009, p. 614.

- ^ Levine 2009, pp. 556–557.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 207.

- ^ Mote 1999, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Levine 2009, p. 615.

- ^ Levine 2009, p. 615; Mote 1999, p. 208.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 208; Ropp 2010, p. 71.

- ^ Ropp 2010, p. 71.

- ^ Smith 1991, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Lorge 2005, p. 54.

- ^ Tao 2009, p. 646.

- ^ a b Franke 1994, pp. 229–230.

- ^ a b c d e Franke 1994, p. 230.

- ^ Lorge 2005, p. 54; Gernet 1962, p. 22.

- ^ a b c Tao 2009, p. 647.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 291.

- ^ Franke 1994, p. 230; Mote 1999, p. 197.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 292.

- ^ a b Tao 2009, p. 649.

- ^ Tao 2009, p. 649 (willing to provoke); Franke 1994, pp. 229–230 (Jin control not solidified).

- ^ a b Tao 2009, p. 650.

- ^ Murray 2010, p. 3; Wilson 1996, pp. 571–572.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 293; Tao 2009, p. 650.

- ^ a b Mote 1999, p. 293.

- ^ Tao 2009, p. 652.

- ^ a b c Tao 2009, p. 654.

- ^ a b c d Tao 2009, p. 657.

- ^ a b c Tao 2009, p. 658.

- ^ a b Mote 1999, p. 298.

- ^ a b c d Tao 2009, p. 655.

- ^ a b Tao 2009, p. 660.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 298 (date of return to Hangzhou); Tao 2009, p. 696 (renamed Lin'an).

- ^ Tao 2009, p. 696.

- ^ Gernet 1962, pp. 23–25.

- ^ Tao 2009, p. 697.

- ^ Gernet 1962, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Tao 2009, p. 661.

- ^ Tao 2009, p. 662.

- ^ Mote 1999, pp. 197 (150 years) and 461 (major Song city).

- ^ Tao 2009, p. 673.

- ^ Tao 2009, pp. 673–674.

- ^ a b c Tao 2009, p. 674.

- ^ Franke 1994, pp. 230–232.

- ^ a b Tao 2009, p. 675.

- ^ Paul Jakov Smith, Richard von Glahn (2020). The Song-Yuan-Ming Transition in Chinese History. BRILL. p. 74. ISBN 9781684173815.

- ^ Tao 2009, p. 676.

- ^ Xiaonan Deng (2021). The Ancestors' Instructions Must Not Change: Political Discourse and Practice in the Song Period. BRILL. pp. 555–556. ISBN 9789004473270.

- ^ a b c d Tao 2009, p. 677.

- ^ Tao 2009, p. 679.

- ^ a b c d Tao 2009, p. 682.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 303.

- ^ Mote 1999; Tong 2012.

- ^ a b Lorge 2005, p. 56.

- ^ Tao 2009, p. 684.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 303 (Jurchen pressure); Tao 2009, p. 687 (collusion never proven).

- ^ Tao 2009; Mote 1999.

- ^ Tao 2009, p. 686.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 299.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 301.

- ^ Tao 2009, p. 687.

- ^ Tao 2009, pp. 688–689.

- ^ Hymes 2000, p. 34.

- ^ Beckwith 2009, p. 175.

- ^ Franke 1994, p. 234.

- ^ a b c Franke 1994, p. 235.

- ^ Franke 1994, p. 239.

- ^ a b Franke 1994, p. 240.

- ^ Franke 1994, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Franke 1994, p. 241 (securing borders); Tao 2009, p. 704 (indecisiveness).

- ^ Tao 2009, p. 709.

- ^ a b Franke 1994, p. 241.

- ^ a b c d Franke 1994, p. 242.

- ^ a b Tao 2009, p. 707.

- ^ Tao 2009, p. 706; Needham 1987, p. 166; Turnbull 2002, p. 46.

- ^ Needham 1987, p. 166; Turnbull 2002, p. 46.

- ^ Lo 2012, p. 166.

- ^ Tao, Jing-shen (1976). "Chapter 6: The Jurchen Movement for Revival". The Jurchen in Twelfth-Century China. University of Washington Press. pp. 69–83. ISBN 0-295-95514-7.

- ^ a b Franke 1994, p. 243.

- ^ Tao 2009, pp. 708–709.

- ^ a b Franke 1994, p. 244.

- ^ Franke 1994, pp. 245–247.

- ^ a b c Franke 1994, p. 247.

- ^ Davis 2009, p. 791.

- ^ a b c Davis 2009, p. 793.

- ^ Franke 1994, pp. 247–248.

- ^ Franke 1994; Davis 2009.

- ^ Davis 2009, p. 799.

- ^ a b c Franke 1994, p. 248.

- ^ Davis 2009, p. 796; Tan 1982, pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b Davis 2009, p. 805.

- ^ Davis 2009, p. 796.

- ^ Davis 2009, p. 800.

- ^ Franke 1994, p. 248; Davis 2009, p. 805.

- ^ Davis 2009, pp. 803–804.

- ^ Davis 2009, pp. 808–811.

- ^ a b Franke 1994, p. 249.

- ^ Davis 2009, p. 812.

- ^ Franke 1994, pp. 251–252.

- ^ Davis 2009, pp. 819–821.

- ^ Davis 2009, p. 821.

- ^ Franke 1994, p. 254.

- ^ a b c Franke 1994, p. 259.

- ^ a b c Davis 2009, p. 822.

- ^ Davis 2009, p. 827.

- ^ Franke 1994, p. 259; Davis 2009, p. 829.

- ^ Davis 2009, pp. 827 and 829.

- ^ Davis 2009, p. 827; Levine 2009, p. 538.

- ^ Davis 2009, p. 828.

- ^ Davis 2009, pp. 828–829.

- ^ Davis 2009, p. 829.

- ^ Franke 1994, p. 261.

- ^ a b c d Davis 2009, p. 856.

- ^ a b Franke 1994, p. 264.

- ^ Lorge 2005, p. 73.

- ^ Davis 2009, p. 858.

- ^ Hymes 2000, p. 36.

- ^ Franke 1994, p. 306.

- ^ Franke 1994, p. 271.

- ^ Franke 1994, p. 310.

- ^ Franke 1994, p. 282.

- ^ Franke 1994, pp. 282–283.

- ^ Franke 1994, pp. 239–240; Holcombe 2011, p. 129.

- ^ Franke 1994, p. 250.

- ^ a b Coblin 2002, p. 533.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 461.

- ^ Gernet 1962, p. 25.

- ^ Rossabi 1983, p. 10.

- ^ Tao 2009, p. 701.

- ^ Tao 2009, p. 699.

- ^ Rossabi 1983, p. 8.

- ^ 衣冠南渡. 汉典 [Han Dian] (in Chinese). Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ 中华书局编辑部, ed. (1 January 1999). 全唐诗 [Quan Tang shi] (in Chinese). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. p. 761. ISBN 978-7101017168. OCLC 48425140.

- ^ Guo, Rongxing (2011). An Introduction to the Chinese Economy: The Driving Forces Behind Modern Day China. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0470826751.

- ^ Li, Shi. The History of Science of Song, Liao, Jin and Xixia of Dynasty. DeepLogic.

- ^ Yan, Ping (1998). China in ancient and modern maps (illustrated ed.). Sotheby's Publications. p. 16. ISBN 0856674133.

- ^ Hansen, Valerie; Curtis, Kenneth R. (2012). Voyages in World History, Volume I, Brief. Cengage Learning. p. 255. ISBN 978-1111352349.

- ^ Hansen, Valerie; Curtis, Kenneth R. (2012). Voyages in World History, Complete, Brief. Cengage Learning. p. 255. ISBN 978-1111352332.

- ^ Deng, Gang (2002). The Premodern Chinese Economy: Structural Equilibrium and Capitalist Sterility (illustrated ed.). Routledge. p. 311. ISBN 1134716567.

- ^ Needham 1987, p. 238.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 31 (use of fire lance at De'an); Tao 2009, p. 660 (campaign during which the siege of De'an took place).

- ^ a b Chase 2003, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Lorge 2008, p. 35.

- ^ Needham 1987, p. 222.

- ^ Lorge 2008, p. 36.

- ^ Needham 1987, p. 156; Partington 1960, pp. 263–264.

- ^ Ebrey 2010, p. 168.

- ^ Needham 1987, p. 156; Needham 1954, p. 134.

- ^ Needham 1987, p. 166.

- ^ Needham 1987.

- ^ Needham 1987, p. 156.

- ^ a b Needham 1987, p. 170.

Bibliography

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2.

- Chase, Kenneth Warren (2003). Firearms: A Global History to 1700. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82274-9.

- Coblin, Weldon South (2002). "Migration History and Dialect Development in the Lower Yangtze Watershed". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 65 (3): 529–543. doi:10.1017/S0041977X02000320 (inactive 1 November 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - Davis, Richard L. (2009). "The Reigns of Kuang-tsung (1189–1194) and Ning-tsung (1194–1224)". In Paul Jakov Smith; Denis C. Twitchett (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 5, The Sung dynasty and Its Precursors, 907–1279. Cambridge University Press. pp. 756–838. ISBN 978-0-521-81248-1. (hardcover)

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (2010) [1996]. The Cambridge Illustrated History of China (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-12433-1.

- Franke, Herbert (1994). "The Chin dynasty". In Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke; John K. Fairbank (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 710–1368. Cambridge University Press. pp. 215–320. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5. (hardcover)

- Franke, Herbert; Twitchett, Denis (1994). "Introduction". In Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke; John K. Fairbank (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 710–1368. Cambridge University Press. pp. 2–42. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- Gernet, Jacques (1962). Daily Life in China, on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250–1276. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0720-6.

- Holcombe, Charles (2011). A History of East Asia: From the Origins of Civilization to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51595-5.

- Hymes, Robert (2000). "China, Political History". In John Stewart Bowman (ed.). Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. Columbia University Press. pp. 3–78. ISBN 978-0-231-11004-4.

- Levine, Ari Daniel (2009). "The Reigns of Hui-tsung (1100–1126) and Ch'in-tsung (1126–1127) and the Fall of the Northern Sung". In Paul Jakov Smith; Denis C. Twitchett (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 5, The Sung dynasty and Its Precursors, 907–1279. Cambridge University Press. pp. 556–643. ISBN 978-0-521-81248-1. (hardcover)

- Lo, Jung-pang (2012), China as a Sea Power 1127–1368

- Lorge, Peter (2005). War, Politics and Society in Early Modern China, 900–1795. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-96929-8.

- ——— (2008). The Asian Military Revolution: From Gunpowder to the Bomb. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84682-0.

- Mote, Frederick W. (1999). Imperial China: 900–1800. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-44515-5. (hardcover); ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7 (paperback).

- Murray, Julia K. (2010). "Descendants and Portraits of Confucius in the Early Southern Song" (PDF). Paper Given at the Symposium "Dynastic Renaissance: Art and Culture of the Southern Song", National Palace Museum (Taipei), 22–24 November 2010: 1–18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- Needham, Joseph (1954). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 1, Introductory Orientations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-05799-8.

- ——— (1987). Science and Civilisation in China: Military technology: The Gunpowder Epic, Volume 5, Part 7. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-30358-3.

- Partington, J. R. (1960). A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5954-0.

- Ropp, Paul S. (2010). China in World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-979876-6.

- Rossabi, Morris (1983). "Introduction". China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th–14th Centuries. University of California Press. pp. 1–13. ISBN 978-0-520-04562-0.

- Smith, Paul J. (1991). Taxing Heaven's Storehouse: Horses, Bureaucrats, and the Destruction of the Sichuan Tea Industry 1074–1224. Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University. ISBN 0-674-40641-9.

- Tan, Qixiang 谭其骧 (1982). 中国历史地图集 [The Historical Atlas of China] (in Chinese). Vol. 6, Song, Liao, and Jin Times 宋·辽·金时期. Beijing: China Cartographic Publishing House. ISBN 7-5031-0385-X. OCLC 297417784.

- Tao, Jing-Shen (2009). "The Move to the South and the Reign of Kao-tsung". In Paul Jakov Smith; Denis C. Twitchett (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 5, The Sung dynasty and Its Precursors, 907–1279. Cambridge University Press. pp. 556–643. ISBN 978-0-521-81248-1. (hardcover)

- Tong, Yong (2012). China at War. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-415-3.

- Yue, Isaac (2020). Monstrosity and Chinese Cultural Identity.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2002). Fighting Ships of the Far East: China and Southeast Asia 202 BC – AD 1419 14194. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78200-017-4.

- Twitchett, Denis; Tietze, Klaus-Peter (1994). "The Liao". In Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke; John K. Fairbank (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 710–1368. Cambridge University Press. pp. 42–153. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- Wilson, Thomas A. (1996). "The Ritual Formation of Confucian Orthodoxy and the Descendants of the Sage". Journal of Asian Studies. 55 (3): 559–584. doi:10.2307/2646446. JSTOR 2646446. S2CID 162848825.