Jap

Jap is an English abbreviation of the word "Japanese". In some places, it is simply a contraction of the word and does not carry negative connotations[citation needed], whereas in some other contexts it can be considered a slur.

In the United States, some Japanese Americans have come to find the term offensive because of the internment they had suffered during World War II. Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Jap was not considered primarily offensive. However, following the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the Japanese declaration of war on the US, the term began to be used derogatorily, as anti-Japanese sentiment increased.[1] During the war, signs using the epithet, with messages such as "No Japs Allowed", were hung in some businesses, with service denied to customers of Japanese descent.[2]

History and etymology

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Jap as an abbreviation for Japanese was in colloquial use in London around 1880.[3] An example of benign usage was the previous naming of Boondocks Road in Jefferson County, Texas, originally named Jap Road when it was built in 1905 to honor a popular local rice farmer from Japan.[4]

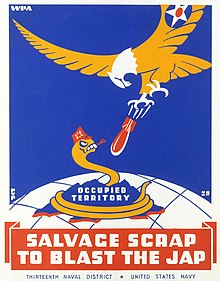

Later popularized during World War II to describe those of Japanese descent, Jap was then commonly used in newspaper headlines to refer to the Japanese and Imperial Japan. Jap began to be used in a derogatory fashion during the war, more so than Nip.[1] Veteran and author Paul Fussell explains the rhetorical usefulness of the word during the war for creating effective propaganda by saying that Japs "was a brisk monosyllable handy for slogans like 'Rap the Jap' or 'Let's Blast the Jap Clean Off the Map'".[1] Some in the United States Marine Corps tried to combine the word Japs with apes to create a new description, Japes, for the Japanese; this neologism never became popular.[1]

In the United States, the term has now been considered derogatory; the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary notes it is "disparaging".[5][6] A snack food company in Chicago named Japps Foods (for the company founder) changed their name and eponymous potato chip brand to Jays Foods shortly after the Attack on Pearl Harbor to avoid any negative associations with Japan.[7]

Spiro Agnew was criticized in the media in 1968 for an offhand remark referring to reporter Gene Oishi as a "fat Jap".[8]

In Texas, under pressure from civil rights groups, Jefferson County commissioners in 2004 decided to drop the name Jap Road from a 4.3-mile (6.9 km) road near the city of Beaumont. In adjacent Orange County, Jap Lane has also been targeted by civil rights groups.[9] The road was originally named for the contributions of Kichimatsu Kishi and the farming colony he founded. In Arizona, the state department of transportation renamed Jap Road near Topock, Arizona to "Bonzai Slough Road" to note the presence of Japanese agricultural workers and family-owned farms along the Colorado River there in the early 20th century. [citation needed] In November 2018, in Kansas, automatically generated license plates which included three digits and "JAP" were recalled after a man of Japanese ancestry saw a plate with that pattern and complained to the state.[10]

Reaction in Japan

Koto Matsudaira, Japan's Permanent Representatives to the United Nations, was asked whether he disapproved of the use of the term on a television program in June 1957, and reportedly replied, "Oh, I don't care. It's a [sic] English word. It's maybe American slang. I don't know. If you care, you are free to use it."[11] Matsudaira later received a letter from the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL),[12] and apologized for his earlier remarks upon being interviewed by reporters from Honolulu and San Francisco.[13] He then pledged cooperation with the JACL to help eliminate the term Jap from daily use.[14]

In 2003, the Japanese deputy ambassador to the United Nations, Yoshiyuki Motomura, protested the North Korean ambassador's use of the term in retaliation for a Japanese diplomat's use of the term "North Korea" instead of the official name, "Democratic People's Republic of Korea".[15]

In 2011, after the term's offhand use in a March 26 article appearing in The Spectator ("white-coated Jap bloke"), the Minister of the Japanese Embassy in London protested that "most Japanese people find the word 'Japs' offensive, irrespective of the circumstances in which it is used".[16]

Around the world

Jap-Fest is an annual Japanese car show in Ireland.[17] In 1970, the Japanese fashion designer Kenzo Takada opened the Jungle Jap boutique in Paris.[18]

In Singapore[19] and Hong Kong,[20] the term is used relatively frequently as a contraction of the adjective Japanese rather than as a derogatory term. It is also used in Australia, particularly for Japanese cars[21] and Japanese pumpkin.[22] In New Zealand, the phrase is a non-pejorative contraction of Japanese, although the phrase Jap crap is used to describe poor-quality Japanese vehicles.

The word Jap is used in Dutch as well, where it is also considered an ethnic slur. It frequently appears in the compound Jappenkampen 'Jap camps', referring to Japanese internment camps for Dutch citizens in the Japanese-occupied Dutch Indies.[23]

In Brazil, the term japa is sometimes used in place of the standard japonês as a noun and adjective. Its use may be inappropriate in formal contexts.[24] The use of japa in reference to any person of East Asian appearance, regardless of their ancestry, can be pejorative.[25]

In Canada, the term Jap Oranges was once very common, and was not considered derogatory, given the widespread Canadian tradition of eating imported Japanese-grown oranges at Christmas dating back to the 1880s (to the degree that Canada at one time imported by far the bulk of the Japanese orange crop each year), but after WW2 as consumers were still hesitant to purchase products from Japan[26] the term Jap was gradually dropped and they began to be marketed as "Mandarin Oranges". Today the term Jap Oranges is typically only used by older Canadians.[citation needed]

In the UK, the term is variously seen as neutral or offensive. For instance, Paul McCartney used the term in his 1980 instrumental song "Frozen Jap" from McCartney II, maintaining that he had not intended to cause offense; the song's title was changed to "Frozen Japanese" for the Japanese market.[27] "Nip" is the term that is usually used in the UK when the intention is to cause offence.[28]

In Finnish, the term japsi (pronounced yahpsi) is frequently used colloquially for anything Japanese with no derogatory meaning, similar to how the term jenkki is used for anything American.[29]

See also

- Nip, a similar slur

- Anti-Japanese sentiment

- Jjokbari (Korean)

- Guizi, Xiao riben (Chinese)

References

- ^ a b c d Paul Fussell, Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War, Oxford University Press, 1989, p. 117.

- ^ Gil Asakawa, Nikkeiview: Jap, July 18, 2004.

- ^ "Jap"[permanent dead link]. From the Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ^ "Tolerance.org: Texas County Bans 'Jap Road'". Archived from the original on September 14, 2005.

- ^ "Jap", Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

- ^ "Oxford Languages | The Home of Language Data". languages.oup.com.

- ^ [1] Archived July 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Nation: Fat Jap Trap". Time. February 28, 1972. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ "Texas Community in Grip of a Kind of Road Rage". September 29, 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29.

- ^ Noticias, Univision. "¿Por qué en Kansas están retirando las matrículas de automóviles con las letras JAP?". Univision. Retrieved 2018-11-28.

- ^ "Protest envoy acceptance of 'Jap'". Densho. Pacific Citizen. 2 August 1957. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ Miyakawa, Wataru (9 July 1957). "Reply to letter regarding use of term "Jap" on a television program". Densho. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ "Matsudaira sorry on acceptance of 'Jap'". Densho. Pacific Citizen. 9 August 1957. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ "Matsudaira to cooperate in JACL campaign to depopularize 'Jap'". Densho. Pacific Citizen. 16 August 1957. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ Shane Green, Treaty plan could end Korean War, The Age, November 6, 2003

- ^ Ken Okaniwa (9 April 2011). "Not acceptable". The Spectator. Retrieved 22 July 2012. His brief letter continued, noting that the term had been used in the context of the then-recent 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, with the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster still-ongoing; "I find the gratuitous use of a word reviled by everyone in Japan utterly inappropriate. I strongly request that you refrain from allowing the use of this term in any future articles that refer to Japan."

- ^ "Homepage". Jap-Fest. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ William Wetherall, "Jap, Jappu, and Zyappu, The emotional tapestries of pride and prejudice"[permanent dead link], July 12, 2006.

- ^ Power up with Jap lunch, The New Paper, 18 May 2006

- ^ "Dept. of Jap. Studies. C.U.H.K. -- Dept. Info". www.cuhk.edu.hk.

- ^ https://justjap.com/ [bare URL]

- ^ "Growing Jap Pumpkins in Australia: A Comprehensive Guide for Gardeners – Farming How". 16 March 2023.

- ^ Walsum, Sander van (2019-08-14). "'In Japan zijn die Jappenkampen nooit een thema geweest'". de Volkskrant (in Dutch). Retrieved 2023-01-07.

- ^ "Combinações inusitadas do sushi brasileiro viram tendência até no Japão". www.uol.com.br.

- ^ Hypeness, Redação (July 7, 2017). "Ele desenhou os motivos pelos quais não devemos chamar asiáticos de 'japa' e dizer que são todos iguais". Hypeness. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ British Columbia Dept. of Agriculture, "Japanese Mandarins" [2] Archived 2013-10-24 at the Wayback Machine, 2008

- ^ PAUL McCARTNEY TALKS McCARTNEY II, SONGWRITING AND MORE! | 1980 Interview, retrieved 2022-08-12

- ^ Vries, Paul de (2022-03-31). "The Welcome Death of a Derogatory Term | JAPAN Forward". japan-forward.com. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- ^ "Kielitoimiston sanakirja".

External links

The dictionary definition of jap at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of jap at Wiktionary- Jap in literature

- U.S. Government publication on spotting Japs