James T. Brady

James T. Brady | |

|---|---|

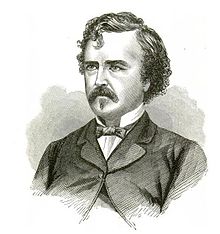

Painting of Brady by Joseph Alexander Ames, 1869 | |

| Born | James Topham Brady April 9, 1815 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | February 9, 1869 (aged 53) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

| Years active | 1835/6–1869 |

James Topham Brady (April 9, 1815 – February 9, 1869) was an American lawyer. Called "one of the most brilliant of all the members of the New York bar",[1] he was born in New York City. Brady studied law in his father's practice before being admitted to the New York bar himself. He is most notable for his career as a criminal lawyer, being involved in numerous high-profile proceedings. He handled fifty-two murder trials and lost only one.[2] Brady died at his home after having suffering two strokes, and was interred in the family vault at Old St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York.

Early life

Brady was born on April 9, 1815, in New York City, the eldest son of Irish immigrants Thomas S. Brady and his wife,[3] who had first settled in Newark, New Jersey in 1812. Later, Brady would have seven siblings, two boys and five girls.[4] James was the elder brother of Judge John R. Brady. Their father had emigrated from Ireland to the United States while the War of 1812 was ongoing, and started a boys school in New York.[5] John McCloskey, later Cardinal Archbishop of the Archdiocese of New York, was a student at the small school.[6] When James was seven, he attended his father's school.[3] In 1831 James's father had left teaching to become a lawyer, and he helped his father in his practice and in trials. In his father's office, James studied legal material tirelessly, and soon operated most of the firm's managerial affairs.[7]

Career

Known familiarly as Jim Brady or James T., he was admitted to the New York Bar in either 1835 or 1836, when he was about twenty years old. His first case was an insurance proceeding, where he opposed the prominent lawyer, Charles O'Conor. The plaintiff staked a claim for insurance money from a property allegedly burned down by a fire. Though Brady lost that case, his proficiency for law and oration was immediately noted.[8] O'Conor would later ask Brady to assist in the defense of Jefferson Davis.

Brady received his first taste of legal notoriety during the Goodyear v. Day patent case, where he worked under Daniel Webster and delivered the opening arguments for the plaintiff.[9][10] Nevertheless, Brady is best known for his work as a criminal lawyer. In the quarter century preceding his death, he was involved in nearly every notable criminal proceeding in the Eastern United States.[11] Among his most famous legal undertakings was the defense of Daniel Sickles during his trial for the murder of Philip Barton Key, the then Attorney General of the District of Columbia. During this trial, Brady worked with Edwin Stanton, who would go on to become the United States Secretary of War. Sickles pled "temporary insanity" and was acquitted. This was the first use of this defense in the United States.[12]

Brady also defended Lew Baker at his trial for the murder of the infamous William "Bill the Butcher" Poole, whom Baker shot to death in 1855 at Stanwix Hall, a bar on Broadway in Manhattan.[11][13] Over his career, Brady tried 52 criminal cases and lost only one, the case of Confederate privateer John Yates Beall. It is said that he never lost a case in which he was before a jury for more than a week; by that time they saw everything with his eyes [14] A fellow attorney called Brady, "Lord of the tear and the laugh."[15] Brady was a fine orator, known for his in-depth preparation, but it was also noted that due to his comprehensive grasp of the law, that when called in for consultation, he could, having heard only the opening arguments, present a concise, successful summation.[16] Brady was particularly successful in criminal cases, in which he usually appeared for the defense, frequently without fee.[1]

It is related that once having successfully defended a man charged with murder, as he was leaving the court the judge said, "Mr. Brady, the next case is that of a man charged with murder; he has no counsel, can you defend him?" "Certainly," said Brady, and instantly went on with the trial. The judge assigned him in the same way to two others charged with a similar crime; so, that in succession, he defended and cleared four capital cases, giving a week's unrequited time to these four criminals.[17]

Brady was a Democrat and was affiliated with Tammany Hall, but refused most requests to run for office.[18] In 1843 he was made the interim district attorney for New York County. Two years later, Brady was appointed the city's corporation counsel, a position in which he served two terms, each term lasting for a year. In 1850 Brady ran for, but was not elected to, the position of Attorney General of New York. Brady was on John C. Breckinridge and Joseph Lane's 1860 Democratic ticket for Governor of New York. When the American Civil War began, Brady switched sides and became an ardent supporter of Abraham Lincoln and his Republican Party. He deeply disdained Southern politics and policy,[11] however, when the government proposed to try Jefferson Davis for treason, Brady was asked to join the defense, and did so without compensation.[19]

Brady enjoyed the New York social and literary society, frequently dining at Delmonico's and occasionally contributing pieces to The Knickerbocker. A friend and patron of New Jersey artist William Ranney, in December 1858, Brady gave a lecture on American art to help defray expenses of the Ranney Exhibition, organized on behalf of Ranney's widow and children.[20]

Personal life and death

Brady remained a lifelong bachelor, living in a mansion on West Twenty-Third Street. When a friend asked why, he said, "When my father died, he left five daughters who looked to me for support. All the affection I could have had for a wife went out to those sisters; and I have never desired to recall it."[3] When his younger brother John became one of the judges in the Court of Common Pleas, Brady ceased from practicing in that forum directly or indirectly.[21] Children took to Brady, and he was fond of them. One of his nieces, affectionately called "Toot", served as his secretary.[17] Around 1848, Mrs. Margaret Ducey came into his employ as housekeeper. When three years later, her eight year old son, Thomas, was left orphaned, Brady took the boy in and saw to his education. He sent the boy to the College of St. Francis Xavier in Chelsea and employed him in his law office,[22] and although he considered Ducey better suited to the practice of law, he covered the young man's expenses to attend St. Joseph's seminary in Troy, New York.

On Sunday, February 7, 1869 Brady suffered a stroke which left him paralyzed on the left side, followed some hours later by a second stroke. His brother John sent for the recently ordained Father Ducey, who administered last rites. Brady died at the age of 53 at his home in New York around daybreak on the morning of February 9.[11] Upon his colleagues learning of his death, that morning the United States Circuit and District Courts, the Court of Oyer and Terminer, the Supreme Court, and other courts in the city, once called into session were then immediately adjourned out of respect.[23] Brady's funeral was held at St. Patrick's Old Cathedral, and he was interred in the Brady family vault there.[24]

References

- ^ a b "Brady, James T.", The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, Volume 3, J. T. White Company, 1893, p. 387

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Brady, James Topham (1815-1869)", Lehigh University

- ^ a b c Clarke 1869, p. 716.

- ^ Houghton 1885, p. 459.

- ^ Clarke 1869, p. 716; Scott 1891, p. 65

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Clarke 1869, p. 716–717.

- ^ Scott 1891, p. 67.

- ^ Spassky 1965, p. 53.

- ^ Unknown 1869, p. 780.

- ^ a b c d "Death of James T. Brady-Sketch of His Life and Character" (PDF). The New York Times. 1869.

- ^ Stankowski, J. E. (2009). "Temporary Insanity". Wiley Encyclopedia of Forensic Science. doi:10.1002/9780470061589.fsa272. ISBN 9780470018262.

- ^ "Terrible Shooting Affray in Broadway; Bill Poole Fatally Wounded". The New York Daily Times. February 26, 1855. p. 1. (Wikisource)

- ^ Clarke 1869, p. 722.

- ^ In Memoriam, p. 47.

- ^ In Memoriam, p. 46.

- ^ a b Clarke, Edwards, "A Great Advocate: James T. Brady", The Galaxy, 7, (January-July, 1869), 716

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Myers, Gustavus (1901). The History of Tammany Hall. New York, NY: Gustavus Muers. p. 232 – via Google Books.

- ^ Nicoletti, Cynthia. Secession on Trial: The Treason Prosecution of Jefferson Davis, Cambridge University Press, Oct 13, 2017, pp. 29-30ISBN 9781108247610

- ^ American paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, (Kathleen Luhrs, ed.), Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1965, p. 53ISBN 9780870994395

- ^ In Memoriam, p. 45.

- ^ McNamara, Pat. "Corporate Greed Attacked from Pulpit, 1900", McNamara's Blog, Patheos, March 27, 2011

- ^ Bar of the city of New York (1869). In Memoriam: James T. Brady. Report of Proceedings at a Meeting of the New York Bar, Held in the Supreme Court Room, Saturday, February 13, 1869 (Report). Baker, Voorhis. pp. 33 et seq.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "A Few of the Faithful Departed Interred on the Grounds of the Basilica of St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral", Saint Patrick's Old Cathedral

Bibliography

- Clarke, I. Edwards (May 1869). "James T. Brady". The Galaxy. 7 (5).

- Houghton, Walter Raleigh (1885). Kings of fortune; or, The triumphs and achievements of noble, self-made men, whose brilliant careers have honored their calling, blessed humanity, and whose lives furnish instruction for the young, entertainment for the old, and valuable lessons for the aspirants of fortune. London: A.E. Davis & Co.

- Scott, Henry Wilson (1891). Distinguished American Lawyers: With Their Struggles and Triumphs in the Forum. Charles L. Webster and Company.

- Spassky, Natalie (1965). Luhrs, Kathleen (ed.). American Paintings: A Catalogue of the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Volumes 1-2. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87099-439-5.

- Unknown (1869). The American Law Review, Volume 3. Little, Brown and Company.