Jacques Chenevière

Jacques Chenevière | |

|---|---|

(1923) | |

| Signature | |

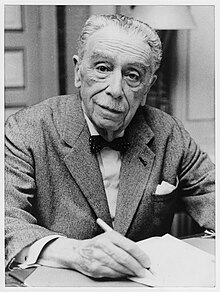

Jacques-Louis-Edmond Chenevière[1] (17 April 1886, Paris – 22 April 1976, Bellevue GE, Switzerland), commonly known as Jacques Chenevière, was a Swiss poet, librettist and novelist from a Patrician family in Geneva. For more than sixty years, he also served as a humanitarian official in top-positions of management and organisation at the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).[2]

The award-winning author, whose father Adolphe Chenevière (1855–1917) was a critically acclaimed man of letters as well, wrote in French and became most famous for his works of psychological fiction. The external contexts of the plots were mostly set in Paris, Geneva or Provence. His Œuvre comprises ten novels, two books of poems as well as several essays, lyrics and novellas. He was widely considered to be one of the most important representatives of literature from Romandy in the 20th century.[3]

Shortly after the beginning of the First World War, Chenevière took up a leading role in the International Prisoners-of-War Agency (IPWA). In 1919 he was elected as a member of the ICRC and in 1923 became its director-general. During the Second World War he was appointed the director of the Central Information Agency on Prisoners-of-War as well as of the Central Bureau of the ICRC. In 1945, he rose to be its vice-president for the first time. Within the ICRC leadership he belonged to the legalistic group which prevented a public denounciation of the Nazi-terror regime.[4] In recent years, the ICRC has recognised that its silence about the holocaust was «the greatest failure» in its history.[5]

Chenevière remained a regular member of the ICRC for half a century, which made him the one with the second-longest term of office in the history of the organisation. Upon his retirement in 1969 he was made an honorary member. A decade earlier he had been appointed as the first ever honorary vice-president of the ICRC.[6]

Life

Family background

Chenevière's paternal family originated from L’Arbresle near Lyon. Since many of his forefathers were Protestant pastors, it may be assumed that they like many other Huguenots fled to Geneva because of the French Wars of Religion. In 1631, the Chenevières obtained Genevan citizenship. Their descendants are thus officially amongst the ten oldest families of the city.[2] Jacques Chenevière's great-grandfather was Jean-Jacques-Caton Chenevière (1783–1871), who became a professor of dogmatic theology and played a major role in Genevan politics of the 19th century.[7]

Jacques Chenevière's grandfather Arthur Chenevière (1822–1908) worked at the Banque Bonna & Cie which became what is today the private bank Lombard Odier & Co, one of the biggest players in the Swiss financial sector. In 1868, he founded the Banque Chenevière & Cie and later also became a board member of BNP Paribas and other banks. At the same time, he was the controversial leader of the Parti indépendant («Independent Party»). During a feud about election results in 1864 some of his supporters even had a bloody shoot-out in the city centre with followers of a rival party. Between 1864 and 1871, he led the treasury of the canton of Geneva, before serving as a member of the Grand Council of Geneva until 1888 and as a member of the National Council from 1878 until 1884.[8] Arthur Chenevière was married to Susanne-Firmine Munier, a daughter of the influential theologian David-François Munier (1798-1872).[9] A street in Cologny, one of the wealthiest municipalities in Switzerland, is named after the couple.[10] The plot of land, where the Villa Chenevière used to be, is nowadays the seat of the World Economic Forum (WEF).[11]

While two sons of Arthur and Susanne-Firmine became bankers as well and their daughter married the founder of the Union Bank (later UBS),[12] their brother Adolphe did not pursue his career as an advocate but instead became a novelist and essayist. The four siblings thus embodied the development of their Patrician class, which

«turned to banking and philanthropic activities at the end of the 19th century, after losing control of the major public offices in Geneva.»[13]

Adolphe moved to Paris around 1880, where he worked as a literary critic at the prestigious Revue des Deux Mondes,[14] which is today the oldest still existing cultural magazine in Europe. Jacques’ mother Blanche (1865–1911), née Lugol, originated from an area close to Nîmes, where her family owned the wine-growing estate of Campuget.[15] In his youth, Jacques Chenevière spent much of his holidays in Provence[16] and Languedoc, which evidently inspired his literary works.[17] The critic Charlotte König-von Dach argued that Jacques' mother gave him

«the sparkling verve, the luster, and the mobility of poetic intuition as gifts from the Midi de la France, in contrast to the heavier calvinist-protestant blood of Geneva».[18]

Jacques Chenevière grew up as a de facto single-child, since his younger brother André Alfred died in 1888 shortly after birth.[19]

Education and early career

Chenevière spent his childhood and youth in Paris during the cultural heyday of the Belle Époque. Thanks to his privileged family background he had access to gatherings of artists like the famous salon of the painter Madeleine Lemaire (1845–1928).[20] At a young age already he thus had personal encounters with luminaries like novelist Marcel Proust (1871–1922), the composer Reynaldo Hahn (1874–1947) and the stage actress Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923).[21] Meanwhile, he received his secondary school education at the elitist Lycées Carnot[22] and Condorcet.[23] He subsequently graduated from Sorbonne Université with a degree in humanities.[22]

In 1906, Chenevière published his first poems in the Revue de Paris. Three years later, a Parisian publishing company published his first book of poems: Les beaux jours («The beautiful days»). The Académie Française honoured the debut with the Prix Archon-Despérouses, an award for young poets.[22] Shortly afterwards, Chenevière was commissioned by the French composer Louis Aubert (1877–1968) to write the lyrics for the Opéra-comique La forêt bleue («The blue forest»), which premiered in Boston at the end of 1911.[24]

When Chenevière's mother suddenly died in late 1911 from an embolism at the age of 46 years,[25] he increasingly turned towards Geneva, which he only knew from the holidays he spent there.[22] Hence, he started developing a life-long friendship with the Genevan composer and music educator Émile Jaques-Dalcroze (1865–1950),[26] the founder of Dalcroze eurhythmics. Chenevière wrote the lyrics for the chorus of Jaques-Dalcroze's miming piece Eco e Narciso («Echo and Narcissus»), which premiered in 1912 at Jaques-Dalcroze's newly opened Hellerau Festival House near Dresden.[27]

In 1913, Chenevière published his second book of poems: La chambre et le jardin («The chamber and the garden»). Many of the poems were also syndicated to the Revue de Paris, the Revue des Deux Mondes, for which his father worked, and to Swiss papers.[28] In early 1914, Chenevière[29] and his father moved from Paris to Geneva.[14]

World War I

Shortly after the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the ICRC under its president Gustave Ador established the International Prisoners-of-War Agency (IPWA) to trace POWs and to re-establish communications with their respective families. Chenevière was one of the first to register as a volunteer at the IPWA in September.[30] He was joined by his father.[31] The Austrian writer and pacifist Stefan Zweig described the situation during those early days at the agency as follows:

«Hardly had the first blows been struck when cries of anguish from all lands began to be heard in Switzerland. Thousands who were without news of fathers, husbands, and sons in the battlefields, stretched despairing arms into the void. By hundreds, by thousands, by tens of thousands, letters and telegrams poured into the little House of the Red Cross in Geneva, the only international rallying point that still remained. Isolated, like stormy petrels, came the first inquiries for missing relatives; then these inquiries themselves became a storm. The letters arrived in sackfuls. Nothing had been prepared for dealing with such an inundation of misery. The Red Cross had no space, no organization, no system, and above all no helpers.»[32]

However, by the end of 1914 there were already some 1,200 volunteers working at the IPWA which was then housed inside the Musée Rath. Amongst them was the French novelist and pacifist Romain Rolland,[33] who was given his initial tasks by Chenevière.[21] When Rolland was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature for 1915, he donated half of the prize money to the Agency.[33]

Most of the staff were women though. Some of them came from the Patrician class of Geneva and joined the IPWA because of male relatives in high ICRC positions, which was all-male for more than half century. This group included female pioneers like the legal scholar and historian Marguerite Cramer, the art historian Marguerite van Berchem, and the Dalcroze eurhythmics educator Suzanne Ferrière. The connection between the Chenevières came through family tradition and bonds as well: Adolphe's younger brother Edmond (1862–1932) was married to a daughter of the Milanese banker Charles Brot, who played a role when the ICRC was founded. The wife of Adolphe's older brother Alfred-Maurice (1848–1926) was related to the families of ICRC co-founder Gustave Moynier (1826–1910) and of his successor Ador.[2]

Under those conditions, Chenevière quickly rose to become the co-director of the IPWA department which was responsible for the Triple Entente of the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.[34] Upon the suggestion of his co-director Cramer they established a system,[35] which could cope with the flood of incoming information through index cards and catalogues.[36]

At the same time, Chenevière established himself further in the cultural life of Geneva. Most notably, he joined the child psychologist Édouard Claparède (1873–1940) and his brother-in-law Auguste de Morsier (1864–1923), a prominent proponent of women's suffrage, to collect funds for Jaques-Dalcroze who was thus able to found his own institute in October 1915. The academy still exists today in the Eaux-Vives quarter of Geneva in the building which was purchased at the time from those donations.[27] Chenevière also supported Georges Pitoëff, a student of Jaques-Dalcroze, when he founded his theatre group.[37]

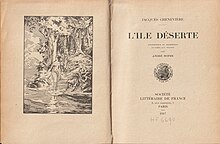

Moreover, Chenevière continued to work on his own literary career: in 1917, his first novel was published under the title L’île déserte («The lonely island») by Éditions Bernard Grasset, one of the most important literary publishing companies in France. The plot about a Parisian man and a woman who get stranded on a polynesian atoll and gradually overcome their mutual resentments, was a scandalous affront for large swaths of the Calvinist-puritan upper-class.[38] It is a striking example of Chenevière's «biting satire of the Genevan society which was imprisoned in its corset of moralism».[39]

At the end of 1917, just a few months after Chenevière's father Adolphe had died at the age of 63 years,[31] the ICRC received its first Nobel Peace Prize (ICRC founder Henry Dunant had been ousted because of his personal bankruptcy by co-founder Moynier and hence received the first Nobel Peace Prize in 1901 as an individual). It was the only prize awarded during the war years. Chenevière as the co-director of the Entente-department at the IPWA had contributed accordingly to the honour.

Shortly before the end of the war, Jaques-Dalcroze premiered in his institute the eurhythmic show Les premiers souvenirs («The first memories») for which Chenevière had written the lyrics.[40]

Between the World Wars

In November 1919, the ICRC assembly voted for Chenevière to become its member.[41] He subsequently worked in several commissions of the organisation, e.g. the one which decided upon the foreign missions of delegates and those which conducted negotiations with the newly founded League of National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.[2]

In August 1920, Chenevière and Marguerite Oehl got married in Neuchâtel.[42] The bride, who was thirteen years younger than the groom, had graduated in the previous year with a diploma from the Institut Jaques-Dalcroze.[43] The couple moved into the luxurious Villa Hauterive («High Shore») in Cologny. The estate had originally been owned by the Turrettini family of prominent theologians. Before the Chenevières it had hosted other famous tenants, amongst them the Austrian-Hungarian composer Franz Liszt (1811–1886), the Swiss landscape painter Barthélemy Menn (1815–1893) and the French landscape painter Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot (1796–1875), as well as the French artillery officer Alfred Dreyfus (1859–1935) after his acquittal in the Dreyfus affair.[14]

The Chenevières lived in the mansion for a dozen years and made it a centre of romand and French high culture. Regular guests in their salon were the literary writers Gonzague de Reynold (1880–1970), Robert de Traz (1884–1951), Edmond Jaloux (1878–1949), Valery Larbaud (1881–1957), François Mauriac (1885–1970), Guy de Pourtalès (1881–1941) and Paul Valéry (1871–1945) as well as the composers Igor Strawinsky (1882–1971) and Jaques-Dalcroze.[14] In 1922, Jacques Chenevière once more wrote lyrics for the grandmaster of eurhythmics, this time for La fête de la jeunesse et de la joie («The festival of youth and joy»).[44]

In 1923, ICRC president Ador – who was Chenevière's nextdoor neighbour in Cologny[14] – appointed him as director-general.[2] Since the end of the Greco-Turkish War in the previous year a relatively calm period set in which lasted until the beginning of the Chaco War in 1932. This left Chenevière with more time for his literary activities:

In 1925, Chenevière took over the co-editorship of the Bibliothèque universelle et Revue de Genève,[39] which supported the principal mission of the Geneva-based League of Nations to foster international understanding and maintain world peace. With his childhood friend de Traz,[22] who like him was born in Paris as the son of a Swiss father and a French mother,[45] he especially promoted the revival of literary exchanges between the German- and French-speaking worlds. In this context they managed, for instance, to make the works by Thomas Mann and Rainer Maria Rilke socially acceptable in France again. The monthly magazine was published until 1930.[46]

In May 1930, the Swiss Schiller Foundation awarded Chenevière for his novel Les messagers inutiles («The useless messengers»).[47] At the same time, he was nominated by the Federal Council to serve as its representative on the board of that foundation,[48] which he remained a member of for a quarter of a century.[49]

In the years before the Second World War, Chenevière increased his activities at the ICRC. On the one hand side, he dealt with issues surrounding humanitarian assistance during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939).[4] On the other hand, he was a member of a commission that dealt with relief operations during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, a war of aggression and conquest which fascist Italy waged against the Ethiopian Empire in East Africa between 1935 and 1937.[2] When the ICRC in March 1936 received reports from its delegate Marcel Junod, a medical doctor, about the Italian use of chemical weapons in Korem, ICRC-president Max Huber travelled to Rome with Chenevière and Carl Jacob Burckhardt, who was a professor of history at the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva and a leading ICRC-member as well. According to Chenevière, Huber – a scholar of international law – mentioned the issue of poison gas warfare during a brief audience with dictator Benito Mussolini. During the internal debate which followed upon their return to Geneva, Chenevière joined the group of lawyers around Huber against the idealist faction led by Lucie Odier, a former nurse. The legalists argued that the ICRC had no legal mandate to denounce the use of weapons of mass destruction. They prevailed and eventually the ICRC only sent a cautious letter to the Italian Red Cross[50]

World War II

On 1 September 1939 – the very day of the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union – the Revue de Paris published an essay by Chenevière on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of the first Geneva Convention in which he stressed that the ICRC and the whole Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement was ready and prepared for humanitarian interventions with regard to the lingering conflicts.[51] Two weeks later, the ICRC opened the Central Agency for Prisoners of War. As the successor of the IPWA from WWI its mandate was based on the 1929 Geneva Convention. The ICRC leadership appointed Chenevière as its director.[2]

When Nazi Germany started its Western Campaign on 10 May 1940 by invading the neutral states of the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxemburg, Chenevière reacted immediately by expanding the Central Agency. By the time of the German victory over France at the end of June it had already almost one thousand volunteers. As in the First World War, most of them were women. In order to cope with the information which came in as an unprecedented flood due to the new dimensions of human suffering, Chenevière introduced a modern data processing system which used punched cards. The US-based technology company IBM provided six pieces of unit record equipment for free. They were nicknamed Watson-machines and could tabulate, sort and cataolgue large numbers of index cards with unprecedented speed. It is, however a bitter irony of history that the Nazi regime on its part also used IBM technology to systematically organise the genocidal persecution of minorities in Europe.[52]

In November 1941, Chenevière travelled to Vichy, where he discussed the situation of the French POWs in the German Reich with Marshal Philippe Pétain.[53] At the same time, Chenevière received a first report about the so-called Final Solution, the genocide of European Jews by Nazi Germany and its collaborators. The Swiss ambassador in Bucharest, René de Weck (1887–1950), who as a romand poet and novelist was an old friend of Chenevière's, sent a private letter to him[54] with an alarming message:

«Dear Chenevière, As I am sure you are aware, the Jews of Romania have for some time, particularly since the country's declaration of war against the USSR, been the object of systematic persecution, compared to which the massacres in Armenia which aroused such indignation in Europe at the dawn of our century seem as harmless as children's games. [..] inhuman acts of violence, despoilments of every kind, deportations, executions and massacres which have taken place.»

De Weck strongly suggested that the ICRC send a delegate under the pretext of another mission to Romania where he could then gather relevant information. De Weck was certain that thanks to the reputation of the ICRC the Romanian government would not ignore the resulting recommendations: «Thousands of lives now under threat could thus be saved.» However, despite the urging, Chenevière only replied more than a month later that «we do not feel able to resolve the question which you put to me».[4]

In 1942, the University of Geneva awarded an honorary doctorate in humanities to Chenevière.[55] In the same year, he took over the editorship of the book review page at the Journal de Genève,[56] a liberal daily newspaper, which had contributed to the founding of the ICRC by publishing a report by Dunant about the Battle of Solferino.[57] He kept that position for about a decade.

By the autumn of 1942 the ICRC had received more reports about the ongoing holocaust. In the plenary session on 14 October a clear majority of its members – led by Marguerite Frick-Cramer, Suzanne Ferrière and Lucie Odier – supported as the ultimate intervention a public denouncation of the genocide. However, the top-leaders around Burckhardt, who chaired the meeting since president Huber had fallen ill, and Philipp Etter, who was not only a member but also the powerful President of the Confederation, rejected this proposal steadfastly. Chenevière sided with his friend Burckhardt,[4] who was married to a daughter of Chenevière's right-wing-authoritarianist friend Gonzague de Reynold[58] (Etter was widely considered to be a disciple of Gonzague de Reynold).[59] The legalists argued that an open protest against the Nazi-terror regime would jeopardise the charitable activities of the ICRC. Chenevière warned on several other occasions as well about the consequences of any extension of its protection efforts and insisted that the ICRC should stick to its traditional operations, especially taking care of POWs.[4]

In 1943, Chenevière published his novel Les captives («The captives»), which is generally considered as his masterpiece.[60] While the plot does not refer directly to the catastrophes of the Second World War,[18] the book reviews suggest that the moral struggles at the ICRC did have a major impact on it. As one put it:

«Its theme is the unfathomable human heart, shackled by distrust and barricades of defense. From these dark chambers the doom of a whole house is caused. In inescapable consistency events get rolling which have been set in motion by men from within their own chests. Nothing turns out to be good, not even the possibility of a compromise appears anywhere on the horizon of this beset world. The law of great tragedy reigns here; entanglement and downfall of a character from the fatal conditions of his own nature.» [61]

In late 1944, the Norwegian Nobel Committee announced that it awarded the ICRC its second Nobel Peace Prize after 1917. As in World War I, it was the only recipient during the war years. The jury in Oslo credited the ICRC with its Central Agency, led by Chenevière, for

«the great work it has performed during the war on behalf of humanity.»[62]

Post-WWII

In June 1946, Chenevière published a lengthy article in the Revue de Paris about the ICRC activities during WWII.[63] Towards the end of the essay he also dealt with the question why the ICRC remained silent about the Shoa. However, he deliberately failed to mention the fact that his friend de Weck had suggested to him in 1941 a promising way to obtain independent information:

«People have expressed surprise that the ICRC did not protest publicly while there was still time. But what could it have protested about? Its own powerlessness? But all the states that were signatories to the Conventions knew the reason and yet failed to make any protest themselves. Could it have protested against the brutal treatment the deportees claimed they were suffering from? But the ICRC had no way of confirming, even partially, such statements. Besides, experience proved that public protests by the ICRC not supported by observations of its own were fruitless, doing more harm than good. In the absence of hard proof they were taken by the accused country as evidence of a priori bias, and put in jeopardy the other activities which the Red Cross was duty bound under the Conventions to carry out.

Protest can be the last resort of the weak. Or they can be a quick way of salving our conscience and giving us the illusion of having done something. Even then, anyone indulging in them needs to be totally free of obligations that imply effective action. Some will always say 'the public must be told'. But that often amounts to a call for reprisals, and the Red Cross must never take the risk of stoking a fire that is ever ready to flare up. So it was in silence, though with all its strength, that the ICRC laboured on behalf of the deportees.

The afore-mentioned is the description of a tragic problem and not an act of self-justification.»[4]

In May 1947, Chenevière as well as his old friend Jaques-Dalcroze and the painter Alexandre Blanchet received the Prize of Geneva in the city's theatre. It was awarded for the first time that year[64] and henceforth every three years to honour artists who had increased the reputation of Geneva.[65]

Upon the occasion of the 30th anniversary of his ICRC membership, the ICRC assembly awarded Chenevière at the end of 1949 the gold medal of the organisation.[6] He was only the second person after Huber who received that honour.[66] At the same time, Chenevière remained active at the top of the organisation as a member of the presidential council, as chairman of the commission for external affairs[67] and from 1950 until 1952 once more as vice-president. He thus continued to participate both in daily politics and strategic decisions, especially with regard to the humanitarian crises in Algeria,[68] Greece, Indochina, Indonesia, Korea, Palestine / Israel, Syria, and Tunisia.[69]

In early 1955, Chenevière retired from the board of the Swiss Schiller Foundation,[49] where he had represented the Federal Council since 1930.[48] However, in June of the same year he still delivered the main speech at the Zürich Town Hall during the award ceremony for the Great Prize of the foundation which honoured Gonzague de Reynold,[70] Chenevière's old friend[53] who as an apologist of Switzerland's aristocratic past and sympathiser of authoritarian regimes was very controversial back then and has remained so ever since.[71] Two years later, Chenevière received the award of the foundation for his own complete works.[72]

In late 1959, upon the 40th anniversary of Chenevière's membership, the ICRC assembly appointed him honorary vice-president. The title was created especially for him.[6] Four years later, the Norwegian Nobel Committee awarded the ICRC its third Nobel Peace Prize after 1917 and 1944. It has remained since then the only organisation which received the award that often. Only Chenevière and Marguerite van Berchem were active top-officials at the ICRC during all three times (Marguerite Frick-Cramer was an honorary member when the Nobel Committee announced its decision in late 1963, a few days before her death).

In 1966, Chenevière published his memoirs, titled Retours et images («Recollections and images»), in which he however did not revisit the silence about the holocaust. At the end of the same year, the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium awarded him its Grand Prize for French-language literature from outside of France.[73] In 1968, the Académie française once again honoured Chenevière, almost six decades after awarding him as one of the best newcomers in poetry, with the Prix du Rayonnement de la langue et de la littérature françaises.[74]

In November 1969, Chenevière retired for age reasons as ICRC member after half a century. In the history of the organisation only Ador served longer than him. At the same time, the ICRC assembly appointed its honorary vice-president also honorary member. ICRC president Marcel Naville praised Chenevière's constant commitment as well as his

«unique discernment»[6]

Chenevière died on 22 April 1976, just a few days after his 90th birthday, in Bellevue GE,[19] a municipality on Lake Geneva's right bank, close to the ICRC headquarters. The Chenevières had lived there in a lake-view mansion for decades since moving out of the Villa Hauterive in Cologny.[3] Jacques Chenevière was buried in between the graves of his parents and his mother-in-law on the cemetery of Collonge-Bellerive, a municipality on Lake Geneva's left bank, where he had a second residency on the shores. The obituaries in the Swiss newspapers focused on his literary legacy. The daily Thuner Tagblatt noted:

«The vividness with which he portrayed human characters was accompanied by the subtility of his linguistic skills. The knowledge about the severity and the doubtfulness of being went along with a relaxing cheerfulness. It is just fair to call him one of the most important representatives of the Western Swiss and – moreover – the protestant French-language literature of our contemporary times.»[75]

The ICRC published in its journal Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge an encomium that borrowed heavily from the apologia which Chenevière published in 1946, arguing that the ICRC could only work silently behind the scenes and try to convince the actors so that it would not jeoparidise its position as a neutral mediator.[76] Since the public apology of its president Cornelio Sommaruga (* 1932) in 1995, the ICRC had acknowledged that its silence about the holocaust was «the greatest failure» in its history.[5] However, two decades earlier the then leadership still defended the diplomatic reserve, for which Chenevière carried major responsibility, and honoured him as a man

«who gave to the Red Cross the best from his energy, his intelligence and his heart»[76]

Legacy

In early 1987, the Bibliothèque publique et universitaire de Genève organised an exhibition about Chenevière's life and works to celebrate the centenary of his birthday.[77]

In 1991, Chenevière's widow Marguerite died at the age of 92 years.[78]

In 1992, Chenevière's masterpiece Les captives was reissued. In the same year, the Fondation Jacques et Marguerite Chenevière was established in Geneva. Its stated purpose was to spend the income from its capital partly or completely on supporting recognised institutions which assist elderly people, especially women, in need.[79]

The graves of Chenevière and his wife Marguerite, who did not have children, of Marguerite's mother Marie (1864–1957) as well as those of his parents Adolphe and Blanche at the cemetery of Collonge-Bellerive are scheduled to be levelled in 2022.

List of works

Autobiography

- Retours et images, Éditions Rencontre, Lausanne 1966

Biographies and essays

In French

- La comtesse de Ségur, née Rostopchine, Gallimard, Paris 1933

- Campagne Genevoise, Éditions du Griffon, Neuchâtel 1950

- Eloge de Gonzague de Reynold : lauréat du grand prix de la Fondation Schiller suisse, Zurich 1955

In German

- Laudatio für Gonzague de Reynold, gesprochen bei der Übergabe des grossen Preises der Schweizerischen Schillerstiftung im Rathaus Zürich am 5. VI. 1955, Zürich 1955

- Genfer Landschaft, Éditions du Griffon, Neuchâtel 1961

In English

- Countryside Around Geneva, Éditions du Griffon, Neuchâtel 1963

Books of poems

- Les beaux jours, Éditions Alphonse Lemerre, Paris 1909

- La chambre et le jardin, Éditions Alphonse Lemerre, Paris 1913

Libretti

- La forêt bleue, A. Durand, Paris 1911

- Les premiers souvenirs, Impr. de la Tribune de Genève, Geneva 1918

- La fête de la jeunesse et de la joie, Foetisch Frères, Lausanne 1922

Novels and novellas

In French

- L’île déserte, Éditions Larousse, Paris 1917

- Jouvence; ou, La chimère, Éditions Grasset, Paris 1922

- Innocences, Éditions Grasset, Paris 1924

- Les messagers inutiles, Éditions Grasset, Paris 1926

- Daphné, Éditions du Sagittaire, Paris 1927

- La jeune fille de neige, Calmann-Lévy, Paris 1929

- Les aveux complets, Calmann-Lévy, Paris 1931

- Connais ton cœur, Calmann-Lévy, Paris 1935

- Valet, dames, roi, Calmann-Lévy, Paris 1938

- Les captives, Éditions du Milieu du Monde et la Guilde du Livre, Geneva 1943

- Le bouquet de la mariée, R. Julliard, Paris 1955

- Daphné ou, L’école des sentiments, Éditions Rencontre, Lausanne 1969

In German

- Die einsame Insel, Verlag Theodor Knaur, Berlin 1927

- Bube, Damen, König: Lehrjahre der Liebe, Fretz & Wasmuth, Zürich 1939

- Erkenne Dein Herz, Christian Wegner Verlag, Hamburg 1939 und 1948

- Herbe Frucht, Christian Wegner Verlag, Hamburg 1949

References

- ^ "État-civil de Neuchâtel". La Suisse Libérale (in French). 56 (177): 3. 30 June 1920 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ a b c d e f g Diego Fiscalini (1985). Des élites au service d'une cause humanitaire: le Comité International de la Croix-Rouge (in French). Geneva: Université de Genève, faculté des lettres, département d’histoire. pp. 18, 20, 137–138.

- ^ a b "M. Jacques Chenevière a 80 ans". Journal et Feuille d'Avis du Valais. 64 (88): 1. 18 April 1966 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ a b c d e f Favez, Jean-Claude (1999). The Red Cross and the Holocaust. Translated by Fletcher, John; Fletcher, Beryl. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 47, 50–51, 61, 64, 70, 75, 86, 89, 91, 95, 106, 150, 153, 171, 178, 198–200, 248, 286. ISBN 2735108384.

- ^ a b "Commemorating the liberation of Auschwitz". ICRC. 2005-01-27. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ^ a b c d "Hommage à M. Jacques Chenevière" (PDF). Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge (in French) (612): 768–770. October 1969.

- ^ Fatio, Olivier (14 July 2005). "Chenevière, Jean-Jacques-Caton". Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS) (in German). Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ^ Burgy, Etienne (14 July 2005). "Chenevière, Arthur". Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS) (in German). Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ^ Fatio, Olivier (13 February 2009). "Munier, David-François". Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS) (in German). Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ^ "Chemin CHENEVIÈRE-MUNIER | Noms géographiques du canton de Genève". République et Canton de Genève (in French). Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ^ "Cologny, Haut-Ruth: villa Chenevière". Bibliothèque de Genève Iconographie (in French). Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ^ Rossellat, Lionel. "Généalogie de Arthur Chenevière". Geneanet (in French). Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ^ Meyre, Camille (2020-03-12). "Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer". Cross-Files | ICRC Archives, audiovisual and library. Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ^ a b c d e Mayor, Jean-Claude (1991). Chemins et visages de Cologny (in French). Cologny: Commune de Cologny. pp. 173–178, 268–269.

- ^ "Photocopies de documents concernant la famille de Mme Adolphe Chenevière, née Blanche Lugol, [mère de Jacques Chenevière]". Bibliothèque de Genève - Manuscrits et archives privées (in French). Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ^ "Poetisches Panorama der Provence". Die Tat (in German). 16 (27): 8. 29 January 1951 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ Bachmann, Jakob (4 April 1970). "Jacques Chenevière". Die Tat (in German). 35 (78): 34 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ a b von Dach, Charlotte (5 December 1943). "Jacques Chenevière". Der Kleine Bund – Literarische Beilage des Bunds. 94 (569): 386–387 – via e-newspaperarchives.com.

- ^ a b Rossellat, Lionel. "Généalogie de Jacques Chenevière". Geneanet (in French). Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ^ Dutoit, Ernest (1 October 1966). "Quand Jacques Chenevière regarde par-dessus son épaule". Journal de Genève.

- ^ a b de Rougemont, Denis (22 October 1966). "Jacques Chenevière ou la précision des sentiments". Gazette de Lausanne (Supplément littéraire): 27, 30. Archived from the original on 12 November 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Meylan, Jean-Pierre (1969). La Revue de Genève, miroir des lettres europeénnes, 1920–1930. Geneva: Librairie Droz. pp. 23, 33–42. ISBN 978-2-600-03493-7.

- ^ B., M. "Ceux qui s'en vont: Hommage à Jacques Chenevière". Le Courrier.

- ^ "La forêt bleue (Aubert, Louis)". International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP) / Petrucci Music Library. Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ^ "Deuil". Figaro (in French). 6 November 1911.

- ^ Martin, Frank; et al. (1965). Emile Jaques-Dalcroze. L'homme, le compositeur, le créateur de la rythmique. Neuchâtel: La Baconnière. pp. 573–580.

- ^ a b Madureira, José Rafael (2008). Émile Jaques-Dalcroze. Sobre a experiência poética da rítmica – uma exposição em 9 quadros inacabados (in Portuguese). Campinas: Universidade estadual de Campinas, faculdade de educação. pp. 58, 183.

- ^ "Conférence Jacques Chenevière". Oberländer Tagblatt (in French). 67 (31): 4. 6 February 1943 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ "Genève: mort d'un homme de lettres, ancien membre du CICR". La Liberté (in French). 105 (169): 3. 23 April 1976 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ "Les 30 ans d'activité de M. Chenevière". Le Nouvelliste (in French). 41 (209): 2. 7 September 1944 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ a b "Adolphe Chenevière". Journal de Genève (in French). 88 (187): 2. 9 July 1917 – via letempsarchives.ch.

- ^ Zweig, Stefan (1921). Romain Rolland; the man and his work. Translated by Eden, Paul; Cedar, Paul. New York: T. Seltzer. p. 268.

- ^ a b Schazmann, Paul-Emile (February 1955). "Romain Rolland et la Croix-Rouge: Romain Rolland, Collaborateur de l'Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre" (PDF). International Review of the Red Cross (in French). 37 (434): 140–143. doi:10.1017/S1026881200125735. S2CID 144703916.

- ^ Chenevière, Jacques (1967). "Some Reminiscences – The First «Prisoners of War Agency» Geneva 1914–1918" (PDF). International Review of the Red Cross. 75 (294): 291–299. doi:10.1017/S0020860400082528.

- ^ Pache, Nicolas (16 July 2014). "Bern/Genf: Das IKRK erlebt seine Feuertaufe. Tag für Tag bis zu 30 000 Briefe und Pakete". Walliser Bote (in German). 174 (162): 15 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ Palmieri, Daniel (2014). Les procès-verbaux de l'Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre (AIPG) (PDF). Geneva: International Committee of the Red Cross. p. 22.

- ^ Stadler, Edmund (1950). "Georges Pitoëff und die Schweiz". Nachrichten der Vereinigung schweizerischer Bibliothekare und der Schweizerischen Vereinigung für Dokumentation (in German). 26 (1): 45 – via e-periodica.ch.

- ^ Marteau, Jean (1950). "La Croix-Rouge et les lettres. Jacques Chenevière" (PDF). La Croix-Rouge Suisse (in French). 59 (5): 23–24. doi:10.5169/seals-558546 – via e-periodica.ch.

- ^ a b Francillon, Roger (14 July 2005). "Chenevière, Jacques". Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS) (in German). Retrieved 2021-09-29.

- ^ "Les "Premiers souvenirs" à l'Institut Jaques-Dalcroze". La Tribune de Genève (in French). 40 (141): 4. 14 June 1918 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ "Au Comité international de la Croix-Rouge". La Tribune de Genève (in French). 41 (275): 4. 25 November 1919 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ "État-civil de Neuchâtel". La Suisse Libérale (in French). 56 (189): 3. 13 August 1920 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ "Institut Jaques-Dalcroze". La Tribune de Genève (in French). 41 (155): 4. 3 July 1919 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ Stadler, Edmund (2 July 1965). "Emile Jaques-Dalcroze. Zum 100. Geburtstag des Komponisten und Musikpädagogen". Der Bund (in German). 116 (276): 6 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ Jakubec, Doris (11 May 2012). "Revue de Genève". Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS) (in German). Retrieved 2021-10-03.

- ^ Charrier, Landry (2009). La Revue de Genève (1920–1925), les relations franco-allemandes et l'idée d'Europe unie (in French). Geneva: Éditions Slatkine. p. 311. ISBN 978-2-05-102100-5.

- ^ "Fondation Schiller suisse". Le Confédéré (in French). 63: 5. 30 May 1930 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ a b "Schweizerischer Schriftstellerverein". Freiburger Nachrichten (in German). 76 (122): 2. 27 May 1930 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ a b "Carnet des lettres et des arts. M. Jacques Chenevière quitte la fondation Schiller". La Liberté (in French). 87 (43): 4. 20 February 1957 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ Baudendistel, Rainer (March 1998). "Force versus law: The International Committee of the Red Cross and chemical warfare in the Italo-Ethiopian war 1935–1936" (PDF). International Review of the Red Cross. 322: 94–97.

- ^ Chenevière, Jacques (1 September 1939). "Genève et la Croix-Rouge – Un anniversaire 1864–1939". Revue de Paris (in French).

- ^ Crossland, James (2014). Britain and the International Committee of the Red Cross, 1939–1945. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-39955-7.

- ^ a b Chenevière, Jacques (1966). Retours et images. Lausanne: Éditions Rencontre. pp. 185, 278.

- ^ Weck, René de (1941-11-29), Le Ministre de Suisse à Bucarest, R. de Weck, au Membre du Comité International de la Croix-Rouge, J. Chenevière (in French), Diplomatische Dokumente der Schweiz | Documents diplomatiques suisses | Documenti diplomatici svizzeri | Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland | Dodis, retrieved 2021-10-03

- ^ "Listes des docteurs honoris causa - Archives - UNIGE". Archives – UNIGE. Université de Genève (in French). 2013-08-28. Retrieved 2021-10-03.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Roulin, Stéphanie (2002). Gonzague de Reynold. Un intellectuel catholique et ses correspondants en quête d'une chrétienté idéale (1938-1945) (PDF) (in French). Fribourg. p. 186.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Dunant, Henry (9 July 1859). "Faits divers". www.letempsarchives.ch. Journal de Genève. Retrieved 2021-10-03.

- ^ Ruffieux, Roland (24 October 2019). "Burckhardt, Carl Jacob". Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS) (in German). Retrieved 2021-10-05.

- ^ NB, Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek. "1948. Gonzague de Reynold: Die metaphysische Überhöhung". www.nb.admin.ch (in German). Retrieved 2021-10-05.

- ^ Les Captives - Jacques Chenevière - Librairie Mollat Bordeaux (in French).

- ^ "Unser neuer Roman". Der Bund (in German). 107 (440): 4. 20 September 1956 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ "The Nobel Peace Prize 1944". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2021-10-07.

- ^ Chenevière, Jacques (June 1946). "L'action de la Croix-Rouge pendant la guerre". Revue de Paris. 53 (6): 38–54.

- ^ "Le bel anniversaire de Jacques Chenevière". Journal de Genève (in French). 17 April 1956.

- ^ "Die Preise der Stadt Genf". Neue Zürcher Nachrichten (in German). Vol. 105. 6 May 1947. p. 4 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ "Mr. Carl J. Burckhardt receives the Gold Medal of the ICRC" (PDF). International Review of the Red Cross. 1 (8): 444–447. November 1961. doi:10.1017/S0020860400013358. ISSN 0020-8604.

- ^ Bericht über die Tätigkeit des Internationalen Komitees vom Roten Kreuz (1. Januar – 31. Dezember 1953) (in German). Geneva: International Committee of the Red Cross. 1954. p. 3.

- ^ Perret, Françoise; Bugnion, François (2009). From Budapest to Saigon. History of the International Committee of the Red Cross 1956–1965 (PDF). Geneva: International Committee of the Red Cross. p. 150. ISBN 978-2-940396-70-2.

- ^ Rey-Schyrr, Catherine (2017). From Yalta to Dien Bien Phu. History of the International Committee of the Red Cross 1945 to 1955 (PDF). Geneva: International Committee of the Red Cross. pp. 30, 34, 323, 353, 471, 527, 532, 566, 639, 641, 657. ISBN 978-2-940396-49-8.

- ^ "Aus der Laudatio für Gonzague de Reynold". Freiburger Nachrichten (in German). 92 (129): 3. 7 June 1955 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ Buchbinder, Sascha (12 September 2014). "Der nachhaltige Einfluss des Frédéric Gonzague de Reynold - Echo der Zeit - SRF". Schweizer Radio und Fernsehen (SRF) (in German). Retrieved 2021-10-10.

- ^ "Die Preise der Schweizerischen Schillerstiftung". Der Bund (in German). 110 (215): 4. 25 May 1959 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ "Belgischer Literaturpreis für einen Schweizer". Thuner Tagblatt (in German). 90 (276): 9. 24 November 1966 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ "Prix du Rayonnement de la langue et de la littérature françaises". Académie française (in French). Retrieved 2021-10-10.

- ^ P., M. (29 April 1976). "Der Romancier Jacques Chenevière gestorben". Thuner Tagblatt. 100 (99): 2 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ a b "Décès de M. Jacques Chenevière, vice-président d'honneur du CICR" (PDF). Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge (in French): 286–287. May 1976.

- ^ D., J.-F. (11 February 1987). "Jacques Chenevière". Construire (in French). 7: 28 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ Rossellat, Lionel. "Généalogie de Marguerite Oehl". Geneanet (in French). Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ^ "Fondation Jacques et Marguerite Chenevière". Registre du Commerce du Canton de Genève. République et Canton de Genève. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

External links

- Correspondence between Carl Jacob Burckhardt and Chenevière, 17 letters written between 1927 and 1974, from Burckhardt's bequest at the library of the University of Basel

- ICRC film from 1941 with audiovisual recordings of Chenevière between 10:25 and 11:35

- Information about Jacques Chenevière in the data bank of the Bibliothèque nationale de France

- Jacques Chenevière in the Dodis data bank of the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- Literature by and about Jacques Chenevière in the German National Library catalogue

- List of manuscripts by Chenevière in the Kalliope Union Catalog with letters to Georges Borgeaud, Max Rychner and others

- Papiers Chenevière – 6,5 m of records from the family archives ranging from 1631 until 1989 – in the archives of the Bibliothèque de Genève

- Publications by and about Jacques Chenevière in the catalogue Helveticat of the Swiss National Library