Jaca uprising

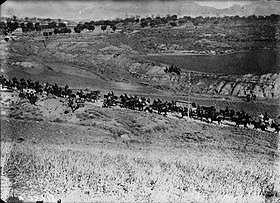

Government troops advance towards Jaca | |

| Native name | Sublevación de Jaca |

|---|---|

| Date | 12–13 December 1930 |

| Location | Jaca, Spain |

| Coordinates | 42°34′21″N 0°33′09″W / 42.572476°N 0.552388°W |

| Type | Military revolt |

| Target | Overthrow the Spanish monarchy |

| Organised by | Fermín Galán Ángel García Hernández |

| Outcome | Suppressed |

The Jaca uprising (Spanish: Sublevación de Jaca) was a military revolt on 12–13 December 1930 in Jaca, Huesca, Spain, with the purpose of overthrowing the monarchy of Spain. The revolt was launched prematurely, was poorly organized and was quickly suppressed. Its leaders were executed or imprisoned. However, the revolt sparked political upheavals that led to declaration of the Second Spanish Republic a few months later.

Background

The Jaca uprising began in the military garrison of the small town of Jaca in the Aragonese Pyrenees.[1] It occurred during a period of growing unrest after six years of dictatorship, first under Miguel Primo de Rivera and then under Dámaso Berenguer. It took place in the context of the mass movements in Europe that followed World War I and the Russian Revolution.[2]

The origins of the revolt can be traced to the Pact of San Sebastián of August 1930, when Republican politicians united with the goal of dethroning King Alfonso XIII of Spain and proclaiming the Second Republic. At the start of autumn they created the Comité Revolucionario Nacional (CRN) and the provisional government of the future republic. The socialists were included in both the CRN and the provisional government after short negotiations, and agreed that workers organized by the Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT: General Union of Workers) would go on strike to support the military wherever they rebelled. Similar arrangements were made with the anarcho-syndicalist Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT: National Confederation of Labour).[2]

The uprising was organized by Captain Fermín Galán.[3] He was assigned to Jaca in June 1930. He wanted to link a military uprising with the political movements opposed to the dictatorship. He established contacts with the CNT in Zaragoza and Huesca, and started a close friendship with the syndicalist leader Ramón Acín of Huesca. When the National Revolutionary Committee (CRN) was created in October 1930, Galán traveled to Madrid to meet the CRN leaders, and was appointed delegate of the CRN in Aragon. From that time he mounted a campaign to get the CRN to support a military uprising at a national level combined with popular demonstrations, but was frustrated by constant postponements of the date.[3]

A significant number of commissioned and non-commissioned officers from different barracks in Jaca participated in the preparations for the revolt, as did some civilians such as Alfonso Rodríguez, Antonio Beltrán, the Palacios brothers and Julián Borderas.[3] Republican leaders generally stayed away from the events, although some people such as the doctor Nicolás Ferrer, the shoemaker Alagón and industrialists Ruiz and Fontana participated actively.[2] The date of 12 December 1930 was agreed, and then postponed by the CRN to 15 December 1930.[3] The CRN representative Santiago Casares Quiroga knew of the decision to delay the uprising and came to Jaca the evening before but did not notify Galán.[4] Casares reached his hotel around midnight. He thought Galán already knew of the delay, and that they could discuss the new plans any time the next day.[5]

Revolt

Events in Jaca

Captain Galán launched the uprising in Jaca in the early hours of 12 December.[6] The uprising began in La Victoria barracks and quickly spread to Ciudadela and Cuartel de los Estudios barracks.[4] A group of officers called out the troops at 5:00 a.m., arrested the military governor, killed two carabineros and a Civil Guard sergeant who opposed them, and took control of the telephone exchange, post office and railway station. At 11:00 a.m. they proclaimed the Republic "on behalf of the Revolutionary Provisional Government" at Jaca city hall.[6]

Pío Díaz Pradas took charge of the Republican mayor's office to show that the new power would have a strictly civil character. At the same time two columns were organized to travel to Huesca. One led by Galán would go by road, while the other led by Salvador Sediles would take the railway.[2] The insurgents looked forward to a triumphant journey of liberation.[1] Delays in requisition of transport by Antonio Beltrán held back the departure from Jaca until 3:00 p.m.[2]

March to Huesca

The poor weather and excessively slow pace of the advance acted against the insurgents.[3] Around 5:00 p.m. General Manuel de las Heras with some Civil Guards met Galán's column at the height of Anzánigo(es). He tried to turn back the column of 500 men by force, and some shots were fired before the column resumed its slow advance.[2] General de las Heras, the military governor of Huesca, was wounded in this action.[3] When they reached Ayerbe the insurgents took control of the telephone and telegraph stations, neutralized the Civil Guard and proclaimed the Republic.[2] The column of 300 soldiers led by Sediles found the railway tracks raised at Riglos, and walked from there to join Galán's column at Ayerbe. The combined force then moved towards Huesca, where conspirators in the artillery were expected to join the rebellion as planned.[3]

Defeat at Cillas

The uprising was halted by officers of the 5th Military Regiment, which was based in Zaragoza.[6] The Captaincy General of the V Military Region organized a counteroffensive once the events in Jaca were confirmed. General de las Heras was replaced by General Joaquim Gay Borràs(ca). On the evening of 12 December troops from Zaragoza under generals Lazcano and Ángel Dolla Lahoz, with troops from Huesca, began to move towards the hills of Cillas. The numerous government troops were supported by artillery, tanks and machine guns.[3] At dawn on 13 December 1930 at the heights of Cillas, about 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) from Huesca, the rebels found themselves confronted by the government force.[2][3]

Galán had a choice of fighting or negotiating. Since he thought many of the opposing troops were under officers committed to the uprising, he chose the latter.[3] The civilian Antonio Beltrán drove Captain Ángel García Hernández and Captain Salinas across the line in a car with a white flag. When they arrived and said they wanted to parley with the officers they were immediately arrested. The government troops then began to fire on the insurgents.[3]

Galán refused to order a counterattack because "brothers cannot fight each other", and ordered withdrawal. Three rebels had died and 25 were wounded. The rebel force disintegrated. Some soldiers and their officers returned to Jaca, some were arrested and some tried to escape.[3] Some managed to find refuge in large cities such as Zaragoza, Barcelona and Madrid and remained under cover until the Republic was declared. Galán voluntarily surrendered in Biscarrués with other rebels and arrived in Ayerbe about 10:00 p.m. on 13 December.[3]

Later events

A general strike was declared in Zaragoza, the capital of Aragon, in the evening of 12 December. The troops that would defeat the rebels had already been transported by rail to Huesca, so it was too late for the railway workers to do anything. By the time the strike took effect in the morning on 13 December the insurgents had surrendered.[1] That morning strikes were also declared in the Cinco Villas.[2] General strikes were declared in the villages of Mallén, Gallur, Tauste, Ejea de los Caballeros, Farasdués(es), Uncastillo, Sádaba and Sos del Rey Católico.[7] A revolutionary committee was set up in Ejea de los Caballeros to try and co-ordinate the movement.[8]

The military responded quickly. Troops from Zaragoza occupied Gallur early in the morning on 14 December, Civil Guards pulled in from villages in the Ebro valley suppressed unrest in Mallén and Gallur and troops were sent to the Cincas Villas villages where the strikers had supported revolution.[8] In Gallur the Civil Guards arrested the village's UGT leaders. In response there was a demonstration in the main square, the Civil Guards panicked and opened fire, although no deaths resulted.[8] On 14 December in a short court martial captains Galán and García Hernández were condemned to death, while other officers were sentenced to life imprisonment.[3] Galán and García Hernández were shot in a courtyard in Huesca at 3:00 p.m. on 14 December 1930. This proved to be a serious mistake since it provoked outrage against the regime.[8]

On 15 December the strikes extended to all of Spain apart from Madrid.[2] Most of the members of the CRN were arrested, as were the trade union leaders. Many of the conspirators in the army were placed under close observation.[3] The uprising planned for 15 December failed. General Gonzalo Queipo de Llano and Major Ramón Franco did capture Cuatro Vientos Airport for a few hours, but when they found that loyalist troops were approaching and no strike had started in Madrid they fled to Portugal. The socialists in Madrid did not go on strike because they did not trust the officers to act, and the officers did not act because they were not supported by a strike and street demonstrations.[6]

General Berenguer resigned two months after the revolt and was succeeded by Admiral Aznar.[8] In March 1931 a number of the insurgent officers and NCOs were tried and sentenced, as were soldiers in Jaca who did not participate but did not try to stop the insurgents. Sediles was condemned to death, but was pardoned before the popular demonstrations spread across Spain on the eve of the municipal elections. The common soldiers who had rebelled were transferred to garrisons in North Africa such as Melilla, Laucién (Tétouan) and Tizitketac.[3]

Aftermath

By coincidence, Margarita Xirgu and Cipriano Rivas Cherif staged Calderón's play El gran teatro del mundo (The great theater of the world) at the Teatro Español in Madrid seven days after Galán was executed. The audience naturally interpreted it as having a revolutionary message.[9] A reviewer said that a tumult of claps and shouts broke out, and a few timid hisses heated up and inflamed matters, when one of the characters said "if we have no King, we will be better off".[10] Manuel Azaña wrote that "The Monarchy committed an outrage in executing Galán and García Hernández, an outrage which in no small way led to its destruction."[6]

Popular unrest grew, and Aznar was forced to call municipal elections in April 1931, in which republican candidates won in all major cities and most provincial capitals.[8] Two days later, on 14 April 1931 the republican leaders proclaimed Spain a republic headed by Niceto Alcalá-Zamora. It became clear that the army leaders would not support the King, and he left Spain that night.[11] Captains Salinas and Sediles both played prominent roles as left-wing republican leaders in 1931 and 1932. Galán and García Hernández became heroes of the Second Republic, with their portraits displayed in council chambers and the homes of workers throughout Spain. However the new leaders of the Republic had done little to support the uprising and did not share its revolutionary goals.[12]

At the start of the Spanish Civil War, in August 1936 many of the protagonists in the uprising were executed by firing squad. In 2010 the town of Jaca erected a memorial to 400 victims of the firing squads.[4] In December 2007 a documentary on the uprising, La sublevación de Jaca. Los capitanes del frío, was released by the filmmaker Miguel Lobera.[13]

Notes

- ^ a b c Kelsey 1991, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Jaca, sublevación de, (1930) – GEA.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Azpiroz Pascual 2000.

- ^ a b c Jaca republicana.

- ^ Gómez 2007, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d e Casanova 2010, p. 75.

- ^ Kelsey 1991, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b c d e f Kelsey 1991, p. 26.

- ^ Kasten 2012, p. 13.

- ^ Kasten 2012, p. 16.

- ^ Phillips & Phillips 2010, p. 246.

- ^ Kelsey 1991, p. 27.

- ^ Pueyo 2007.

Sources

- Azpiroz Pascual, José María (December 2000), "La sublevación de Jaca", Trébede, Cremallo de ediciones S.L., archived from the original on 2018-05-20, retrieved 2018-05-19

- Casanova, Julián (2010-07-29), The Spanish Republic and Civil War, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-139-49057-3, retrieved 2018-05-18

- Gómez, Esteban (2007), "Semblanza Biográfica de Fermín Galán Rodríguez" (PDF), Rolde: Revista de cultura aragonesa (123), ISSN 1133-6676, archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-07-03, retrieved 2018-05-19

- "Jaca republicana", Jaca.com (in Spanish), editorial Pirineum, retrieved 2018-05-19

- "Jaca, sublevación de, (1930)", GEA: Gran Enciclopedia Aragonesa (in Spanish), DiCom Medios SL., archived from the original on 2021-04-10, retrieved 2018-05-18

- Kasten, Carey (2012), The Cultural Politics of Twentieth-century Spanish Theatre: Representing the Auto Sacramental, Lexington Books, ISBN 978-1-61148-381-9, retrieved 2018-05-18

- Kelsey, Graham (1991-11-30), Anarchosyndicalism, Libertarian Communism and the State: The CNT in Zaragoza and Aragon, 1930-1937, Springer Science & Business Media, ISBN 978-0-7923-0275-9, retrieved 2018-05-18

- Phillips, William D. Jr; Phillips, Carla Rahn (2010), A Concise History of Spain, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-60721-6, retrieved 2018-05-18

- Pueyo, Luisa (17 December 2007), ""La sublevación de Jaca. Los capitanes del frío"", Diario del Alto Aragón, retrieved 2018-05-19