Isis

| Isis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

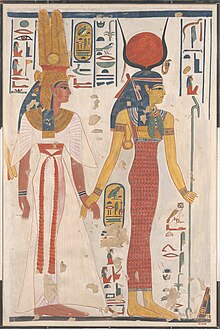

Composite image of Isis's most distinctive Egyptian iconography, based partly on images from the tomb of Nefertari | |||||||||

| Name in hieroglyphs | Egyptian: Ꜣūsat[1][2]

Meroitic: Wos[a] or Wusa[2][3]

| ||||||||

| Major cult center | Behbeit el-Hagar, Philae | ||||||||

| Symbol | Tyet | ||||||||

| Genealogy | |||||||||

| Parents | Geb and Nut | ||||||||

| Siblings | Osiris, Set, Nephthys, Horus the Elder | ||||||||

| Consort | Osiris, Min, Serapis, Horus the Elder | ||||||||

| Offspring | Horus, Min, Four Sons of Horus, Bastet | ||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

|

|

Isis[Note 1] was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kingdom (c. 2686 – c. 2181 BCE) as one of the main characters of the Osiris myth, in which she resurrects her slain brother and husband, the divine king Osiris, and produces and protects his heir, Horus. She was believed to help the dead enter the afterlife as she had helped Osiris, and she was considered the divine mother of the pharaoh, who was likened to Horus. Her maternal aid was invoked in healing spells to benefit ordinary people. Originally, she played a limited role in royal rituals and temple rites, although she was more prominent in funerary practices and magical texts. She was usually portrayed in art as a human woman wearing a throne-like hieroglyph on her head. During the New Kingdom (c. 1550 – c. 1070 BCE), as she took on traits that originally belonged to Hathor, the preeminent goddess of earlier times, Isis was portrayed wearing Hathor's headdress: a sun disk between the horns of a cow.

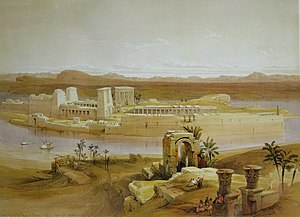

In the first millennium BCE, Osiris and Isis became the most widely worshipped Egyptian deities, and Isis absorbed traits from many other goddesses. Rulers in Egypt and its southern neighbor Nubia built temples dedicated primarily to Isis, and her temple at Philae was a religious center for Egyptians and Nubians alike. Her reputed magical power was greater than that of all other gods, and she was said to govern the natural world and wield power over fate itself.

In the Hellenistic period (323–30 BCE), when Egypt was ruled and settled by Greeks, Isis was worshipped by Greeks and Egyptians, along with a new god, Serapis. Their worship diffused into the wider Mediterranean world. Isis's Greek devotees ascribed to her traits taken from Greek deities, such as the invention of marriage and the protection of ships at sea. As Hellenistic culture was absorbed by Rome in the first century BCE, the cult of Isis became a part of Roman religion. Her devotees were a small proportion of the Roman Empire's population but were found all across its territory. Her following developed distinctive festivals such as the Navigium Isidis, as well as initiation ceremonies resembling those of other Greco-Roman mystery cults. Some of her devotees said she encompassed all feminine divine powers in the world.

The worship of Isis was ended by the rise of Christianity in the fourth through sixth centuries CE. Her worship may have influenced Christian beliefs and practices such as the veneration of Mary, but the evidence for this influence is ambiguous and often controversial. Isis continues to appear in Western culture, particularly in esotericism and modern paganism, often as a personification of nature or the feminine aspect of divinity.

In Egypt and Nubia

Name and origins

Whereas some Egyptian deities appeared in the late Predynastic Period (before c. 3100 BCE), neither Isis nor her husband Osiris were mentioned by name before the Fifth Dynasty (c. 2494–2345 BCE).[5][6] An inscription that may refer to Isis dates to the reign of Nyuserre Ini during that period,[7] and she appears prominently in the Pyramid Texts, which began to be written down at the end of the dynasty and whose content may have developed much earlier.[8] Several passages in the Pyramid Texts link Isis with the region of the Nile Delta near Behbeit el-Hagar and Sebennytos, and her cult may have originated there.[9][Note 2]

Many scholars have focused on Isis's name in trying to determine her origins. Her Egyptian name was written as 𓊨𓏏𓆇𓁐 (ꜣst), the pronunciation of which changed over time: Rūsat > Rūsaʾ > ʾŪsaʾ > ʾĒsə,[2] which became ⲎⲤⲈ (Ēse) in the Coptic form of Egyptian, Wusa in the Meroitic language of Nubia, and Ἶσις, on which her modern name is based, in Greek.[14][Note 3] The hieroglyphic writing of her name incorporates the sign for a throne, which Isis also wears on her head as a sign of her identity. The symbol serves as a phonogram, spelling the st sounds in her name, but it may have also represented a link with actual thrones. The Egyptian term for a throne was also st and may have shared a common etymology with Isis's name. Therefore, the Egyptologist Kurt Sethe suggested she was originally a personification of thrones.[15] Henri Frankfort agreed, believing that the throne was considered the king's mother, and thus a goddess, because of its power to make a man into a king.[16] Other scholars, such as Jürgen Osing and Klaus P. Kuhlmann, have disputed this interpretation, because of dissimilarities between Isis's name and the word for a throne[15] or a lack of evidence that the throne was ever deified.[17]

Roles

The cycle of myth surrounding Osiris's death and resurrection was first recorded in the Pyramid Texts and grew into the most elaborate and influential of all Egyptian myths.[18] Isis plays a more active role in this myth than the other protagonists, so as it developed in literature from the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BCE) to the Ptolemaic Period (305–30 BCE), she became the most complex literary character of all Egyptian deities.[19] At the same time, she absorbed characteristics from many other goddesses, broadening her significance well beyond the Osiris myth.[20]

Wife and mourner

Isis is part of the Ennead of Heliopolis, a family of nine deities descended from the creator god, Atum or Ra. She and her siblings—Osiris, Set, and Nephthys—are the last generation of the Ennead, born to Geb, god of the earth, and Nut, goddess of the sky. The creator god, the world's original ruler, passes down his authority through the male generations of the Ennead, so that Osiris becomes king. Isis, who is Osiris's wife as well as his sister, is his queen.[21]

Set kills Osiris and, in several versions of the story, dismembers his corpse. Isis and Nephthys, along with other deities such as Anubis, search for the pieces of their brother's body and reassemble it. Their efforts are the mythic prototype for mummification and other ancient Egyptian funerary practices.[22] According to some texts, they must also protect Osiris's body from further desecration by Set or his servants.[23] Isis is the epitome of a mourning widow. Her and Nephthys's love and grief for their brother help restore him to life, as does Isis's recitation of magical spells.[24] Funerary texts contain speeches by Isis in which she expresses her sorrow at Osiris's death, her sexual desire for him, and even anger that he has left her. All these emotions play a part in his revival, as they are meant to stir him into action.[25] Finally, Isis restores breath and life to Osiris's body and copulates with him, conceiving their son, Horus.[22] After this point Osiris lives on only in the Duat, or underworld. But by producing a son and heir to avenge his death and carry out funerary rites for him, Isis has ensured that her husband will endure in the afterlife.[26]

Isis's role in afterlife beliefs was based on that in the myth. She helped to restore the souls of deceased humans to wholeness as she had done for Osiris. Like other goddesses, such as Hathor, she also acted as a mother to the deceased, providing protection and nourishment.[27] Thus, like Hathor, she sometimes took the form of Imentet, the goddess of the west, who welcomed the deceased soul into the afterlife as her child.[28] But for much of Egyptian history, male deities such as Osiris were believed to provide the regenerative powers, including sexual potency, that were crucial for rebirth. Isis was thought to merely assist by stimulating this power.[27] Feminine divine powers became more important in afterlife beliefs in the late New Kingdom.[29] Various Ptolemaic funerary texts emphasize that Isis took the active role in Horus's conception by sexually stimulating her inert husband,[30] some tomb decoration from the Roman period in Egypt depicts Isis in a central role in the afterlife,[31] and a funerary text from that era suggests that women were thought able to join the retinue of Isis and Nephthys in the afterlife.[32]

Mother goddess

Isis is treated as the mother of Horus even in the earliest copies of the Pyramid Texts.[33] Yet there are signs that Hathor was originally regarded as his mother,[34] and other traditions make an elder form of Horus the son of Nut and a sibling of Isis and Osiris.[35] Isis may only have come to be Horus's mother as the Osiris myth took shape during the Old Kingdom,[34] but through her relationship with him she came to be seen as the epitome of maternal devotion.[36]

In the developed form of the myth, Isis gives birth to Horus, after a long pregnancy and a difficult labor, in the papyrus thickets of the Nile Delta. As her child grows she must protect him from Set and many other hazards—snakes, scorpions, and simple illness.[37] In some texts, Isis travels among humans and must seek their help. According to one such story, seven minor scorpion deities travel with and guard her. They take revenge on a wealthy woman who has refused to help Isis by stinging the woman's son, making it necessary for the goddess to heal the blameless child.[38] Isis's reputation as a compassionate deity, willing to relieve human suffering, contributed greatly to her appeal.[39]

Isis continues to assist her son when he challenges Set to claim the kingship that Set has usurped,[40] although mother and son are sometimes portrayed in conflict, as when Horus beheads Isis and she replaces her original head with that of a cow—an origin myth explaining the cow-horn headdress that Isis wears.[41]

Isis's maternal aspect extended to other deities as well. The Coffin Texts from the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BCE) say the Four sons of Horus, funerary deities who were thought to protect the internal organs of the deceased, were the offspring of Isis and the elder form of Horus.[42] In the same era, Horus was syncretized with the fertility god Min, so Isis was regarded as Min's mother.[43] A form of Min known as Kamutef, "bull of his mother", who represented the cyclical regeneration of the gods and of kingship, was said to impregnate his mother to engender himself.[44] Thus, Isis was also regarded as Min's consort.[45] The same ideology of kingship may lie behind a tradition, found in a few texts, that Horus raped Isis.[46][47] Amun, the foremost Egyptian deity during the Middle and New Kingdoms, also took on the role of Kamutef, and when he was in this form, Isis often acted as his consort.[45] Apis, a bull that was worshipped as a living god at Memphis, was said to be Isis's son, fathered by a form of Osiris known as Osiris-Apis. The biological mother of each Apis bull was thus known as the "Isis cow".[48] Isis was said to be the mother of Bastet by Ra.[49]

A story in the Westcar Papyrus from the Middle Kingdom includes Isis among a group of goddesses who serve as midwives during the delivery of three future kings.[50] She serves a similar role in New Kingdom texts that describe the divinely ordained births of reigning pharaohs.[51]

In the Westcar Papyrus, Isis calls out the names of the three children as they are born. Barbara S. Lesko sees this story as a sign that Isis had the power to predict or influence future events, as did other deities who presided over birth,[45] such as Shai and Renenutet.[52] Texts from much later times call Isis "mistress of life, ruler of fate and destiny"[45] and indicate she has control over Shai and Renenutet, just as other great deities such as Amun were said to do in earlier eras of Egyptian history. By governing these deities, Isis determined the length and quality of human lives.[52]

Goddess of kingship and protection of the kingdom

Horus was equated with each living pharaoh and Osiris with the pharaoh's deceased predecessors. Isis was therefore the mythological mother and wife of kings. In the Pyramid Texts her primary importance to the king was as one of the deities who protected and assisted him in the afterlife. Her prominence in royal ideology grew in the New Kingdom.[53] Temple reliefs from that time on show the king nursing at Isis's breast; her milk not only healed her child, but symbolized his divine right to rule.[54] Royal ideology increasingly emphasized the importance of queens as earthly counterparts of the goddesses who served as wives to the king and mothers to his heirs. Initially the most important of these goddesses was Hathor, whose attributes in art were incorporated into queens' crowns. But because of her own mythological links with queenship, Isis too was given the same titles and regalia as human queens.[55]

Isis's actions in protecting Osiris against Set became part of a larger, more warlike aspect of her character.[56] New Kingdom funerary texts portray Isis in the barque of Ra as he sails through the underworld, acting as one of several deities who subdue Ra's archenemy, Apep.[57] Kings also called upon her protective magical power against human enemies. In her Ptolemaic temple at Philae, which lay near the frontier with Nubian peoples who raided Egypt, she was described as the protectress of the entire nation, more effective in battle than "millions of soldiers", supporting Ptolemaic kings and Roman emperors in their efforts to subdue Egypt's enemies.[56]

Goddess of magic and wisdom

Isis was also known for her magical power, which enabled her to revive Osiris and to protect and heal Horus, and for her cunning.[58] By virtue of her magical knowledge, she was said to be "more clever than a million gods".[59][60] In several episodes in the New Kingdom story "The Contendings of Horus and Set", Isis uses these abilities to outmaneuver Set during his conflict with her son. On one occasion, she transforms into a young woman who tells Set she is involved in an inheritance dispute similar to Set's usurpation of Osiris's crown. When Set calls this situation unjust, Isis taunts him, saying he has judged himself to be in the wrong.[60] In later texts, she uses her powers of transformation to fight and destroy Set and his followers.[58]

Many stories about Isis appear as historiolae, prologues to magical texts that describe mythic events related to the goal that the spell aims to accomplish.[19] In one spell, Isis creates a snake that bites Ra, who is older and greater than she is, and makes him ill with its venom. She offers to cure Ra if he will tell her his true, secret name—a piece of knowledge that carries with it incomparable power. After much coercion, Ra tells her his name, which she passes on to Horus, bolstering his royal authority.[60] The story may be meant as an origin story to explain why Isis's magical ability surpasses that of other deities, but because she uses magic to subdue Ra, the story seems to treat her as having such abilities even before learning his name.[61]

Sky goddess

Many of the roles Isis acquired gave her an important position in the sky.[62] Passages in the Pyramid Texts connect Isis closely with Sopdet, the goddess representing the star Sirius, whose relationship with her husband Sah—the constellation Orion—and their son Sopdu parallels Isis's relations with Osiris and Horus. Sirius's heliacal rising, just before the start of the Nile flood, gave Sopdet a close connection with the flood and the resulting growth of plants.[63] Partly because of her relationship with Sopdet, Isis was also linked with the flood,[64] which was sometimes equated with the tears she shed for Osiris.[65]

By Ptolemaic times she was connected with rain, which Egyptian texts call a "Nile in the sky"; with the sun as the protector of Ra's barque;[66] and with the moon, possibly because she was linked with the Greek lunar goddess Artemis by a shared connection with an Egyptian fertility goddess, Bastet.[67] In hymns inscribed at Philae she is called the "Lady of Heaven" whose dominion over the sky parallels Osiris's rule over the Duat and Horus's kingship on earth.[68]

Universal goddess

In Ptolemaic times Isis's sphere of influence could include the entire cosmos.[68] As the deity that protected Egypt and endorsed its king, she had power over all nations, and as the provider of rain, she enlivened the natural world.[69] The Philae hymn that initially calls her ruler of the sky goes on to expand her authority, so at its climax her dominion encompasses the sky, earth, and Duat. It says her power over nature nourishes humans, the blessed dead, and the gods.[68] Other, Greek-language hymns from Ptolemaic Egypt call her "the beautiful essence of all the gods".[70] In the course of Egyptian history, many deities, major and minor, had been described in similar grand terms. Amun was most commonly described this way in the New Kingdom, whereas in Roman Egypt such terms tended to be applied to Isis.[71] Such texts do not deny the existence of other deities but treat them as aspects of the supreme deity, a type of theology sometimes called "summodeism".[72][73]

In the Late, Ptolemaic, and Roman Periods, many temples contained a creation myth that adapted long-standing ideas about creation to give the primary roles to local deities.[74] At Philae, Isis is described as the creator in the same way that older texts speak of the work of the god Ptah,[68] who was said to have designed the world with his intellect and sculpted it into being.[75] Like him, Isis formed the cosmos "through what her heart conceived and her hands created".[68]

Like other deities throughout Egyptian history, Isis had many forms in her individual cult centers, and each cult center emphasized different aspects of her character. Local Isis cults focused on the distinctive traits of their deity more than on her universality, whereas some Egyptian hymns to Isis treat other goddesses in cult centers from across Egypt and the Mediterranean as manifestations of her. A text in her temple at Dendera says "in each nome it is she who is in every town, in every nome with her son Horus."[76]

Iconography

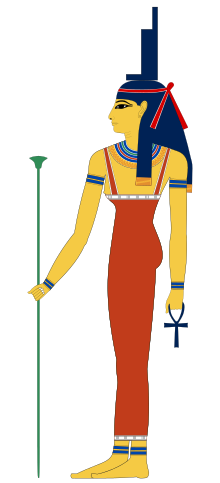

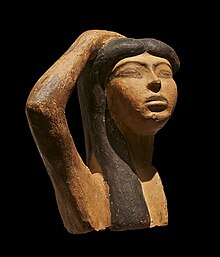

In Ancient Egyptian art, Isis was most commonly depicted as a woman with the typical attributes of a goddess: a sheath dress, a staff of papyrus in one hand, and an ankh sign in the other. Her original headdress was the throne sign used in writing her name. She and Nephthys often appear together, particularly when mourning Osiris's death, supporting him on his throne, or protecting the sarcophagi of the dead. In these situations their arms are often flung across their faces, in a gesture of mourning, or outstretched around Osiris or the deceased as a sign of their protective role.[77] In these circumstances they were often depicted as kites or women with the wings of kites. This form may be inspired by a similarity between the kites' calls and the cries of wailing women,[78] or by a metaphor likening the kite's search for carrion to the goddesses' search for their dead brother.[77] Isis sometimes appeared in other animal forms: as a sow, representing her maternal character; as a cow, particularly when linked with Apis; or as a scorpion.[77] She also took the form of a tree or a woman emerging from a tree, sometimes offering food and water to deceased souls. This form alluded to the maternal nourishment she provided.[79]

Beginning in the New Kingdom, thanks to the close links between Isis and Hathor, Isis took on Hathor's attributes, such as a sistrum rattle and a headdress of cow horns enclosing a sun disk. Sometimes both headdresses were combined, so the throne glyph sat atop the sun disk.[77] In the same era, she began to wear the insignia of a human queen, such as a vulture-shaped crown on her head and the royal uraeus, or rearing cobra, on her brow.[55] In Ptolemaic and Roman times, statues and figurines of Isis often showed her in a Greek sculptural style, with attributes taken from Egyptian and Greek tradition.[80][81] Some of these images reflected her linkage with other goddesses in novel ways. Isis-Thermuthis, a combination of Isis and Renenutet who represented agricultural fertility, was depicted in this style as a woman with the lower body of a snake. Figurines of a woman wearing an elaborate headdress and exposing her genitals may represent Isis-Aphrodite.[82][Note 4]

The tyet symbol, a looped shape similar to the ankh, came to be seen as Isis's emblem at least as early as the New Kingdom, though it existed long before.[84] It was often made of red jasper and likened to Isis's blood. Used as a funerary amulet, it was said to confer her protection on the wearer.[85]

- An illustration of Isis based on a painting in the tomb of Seti I

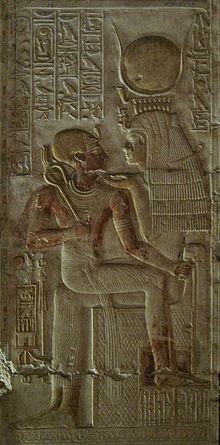

- Isis with a combination of throne-glyph and cow horns, as well as a vulture headdress, Temple of Kalabsha, first century BCE or first century CE

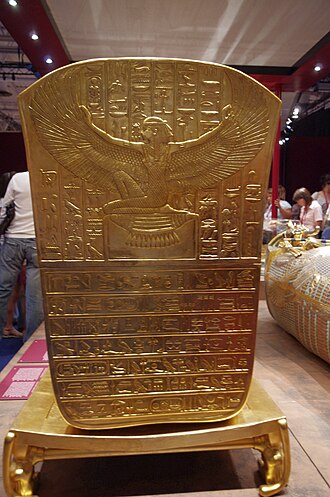

- Winged Isis at the foot of the sarcophagus of Ramesses III, twelfth century BCE

- A relief of winged Isis from the Philae Temple

- Figurine of Isis-Thermuthis, second century CE

- Figurine possibly of Isis-Aphrodite, second or first century BCE

- A tyet amulet, fifteenth or fourteenth century BCE

Worship

Relationship with royalty

Despite her significance in the Osiris myth, Isis was originally a minor deity in the ideology surrounding the living king. She played only a small role, for instance, in the Dramatic Ramesseum Papyrus, the script for royal rituals performed in the reign of Senusret I in the Middle Kingdom.[86] Her importance grew during the New Kingdom,[87] when she was increasingly connected with Hathor and the human queen.[88]

The early first millennium BCE saw an increased emphasis on the family triad of Osiris, Isis, and Horus and an explosive growth in Isis's popularity. In the fourth century BCE, Nectanebo I of the Thirtieth Dynasty claimed Isis as his patron deity, tying her still more closely to political power.[89] The Kingdom of Kush, which ruled Nubia from the eighth century BCE to the fourth century CE, absorbed and adapted the Egyptian ideology surrounding kingship. It equated Isis with the kandake, the queen or queen mother of the Kushite king.[90]

The Ptolemaic Greek kings, who ruled Egypt as pharaohs from 305 to 30 BCE, developed an ideology that linked them with both Egyptian and Greek deities, to strengthen their claim to the throne in the eyes of their Greek and Egyptian subjects. For centuries before, Greek colonists and visitors to Egypt had drawn parallels between Egyptian deities and their own, in a process known as interpretatio graeca.[91] Herodotus, a Greek who wrote about Egypt in the fifth century BCE, likened Isis to Demeter, whose mythical search for her daughter Persephone resembled Isis's search for Osiris. Demeter was one of the few Greek deities to be widely adopted by Egyptians in Ptolemaic times, so the similarity between her and Isis provided a link between the two cultures.[92] In other cases, Isis was linked with Aphrodite through the sexual aspects of her character.[93] Building on these traditions, the first two Ptolemies promoted the cult of the new god Serapis, who combined aspects of Osiris and Apis with those of Greek gods such as Zeus and Dionysus. Isis, portrayed in a Hellenized form, was regarded as the consort of Serapis as well as of Osiris. Ptolemy II and his sister and wife Arsinoe II developed a ruler cult around themselves, so that they were worshipped in the same temples as Serapis and Isis, and Arsinoe was likened to both Isis and Aphrodite.[94] Some later Ptolemaic queens identified themselves still more closely with Isis. Cleopatra III, in the second century BCE, used Isis's name in place of her own in inscriptions, and Cleopatra VII, the last ruler of Egypt before it was annexed by Rome, used the epithet "the new Isis".[95]

Temples and festivals

Down to the end of the New Kingdom, Isis's cult was closely tied to those of male deities such as Osiris, Min, or Amun. She was commonly worshipped alongside them as their mother or consort, and she was especially widely worshipped as the mother of various local forms of Horus.[96] Nevertheless, she had independent priesthoods at some sites[97] and at least one temple of her own, at Osiris's cult center of Abydos, during the late New Kingdom.[98]

The earliest known major temples to Isis were the Iseion at Behbeit el-Hagar in northern Egypt and Philae in the far south. Both began construction during the Thirtieth Dynasty and were completed or enlarged by Ptolemaic kings.[99] Thanks to Isis's widespread fame, Philae drew pilgrims from across the Mediterranean.[100] Many other temples of Isis sprang up in Ptolemaic times, ranging from Alexandria and Canopus on the Mediterranean coast to Egypt's frontier with Nubia.[101] A series of temples of Isis stood in that region, stretching from Philae south to Maharraqa, and were sites of worship for both Egyptians and various Nubian peoples.[102] The Nubians of Kush built their own temples to Isis at sites as far south as Wad ban Naqa,[103] including one in their capital, Meroe.[104]

The most frequent temple rite for any deity was the daily offering ritual, in which priests clothed the deity's cult image and offered it food.[105] In Roman times, temples to Isis in Egypt could be built either in Egyptian style, in which the cult image was in a secluded sanctuary accessible only to priests, and in a Greco-Roman style in which devotees were allowed to see the cult image.[106] Greek and Egyptian culture were highly intermingled by this time, and there may have been no ethnic separation between Isis's worshippers.[107] The same people may have prayed to Isis outside Egyptian-style temples and in front of her statue inside Greek-style temples.[106]

Temples celebrated many festivals in the course of the year, some nationwide and some very local.[108] An elaborate series of rites were performed all across Egypt for Osiris during the month of Khoiak,[109] and Isis and Nephthys were prominent in these rites at least as early as the New Kingdom.[110] In Ptolemaic times, two women acted out the roles of Isis and Nephthys during Khoiak, singing or chanting in mourning for their dead brother. Their chants are preserved in the Festival Songs of Isis and Nephthys and Lamentations of Isis and Nephthys.[110][111]

Festivals dedicated to Isis eventually developed. In Roman times, Egyptians across the country celebrated her birthday, the Amesysia, by carrying the local cult statue of Isis through their fields, probably celebrating her powers of fertility.[112] The priests at Philae held a festival every ten days when the cult statue of Isis visited the neighboring island of Bigeh, which was said to be Osiris's place of burial, and the priests performed funerary rites for him. The cult statue also visited the neighboring temples to the south, even during the last centuries of activity at Philae when those temples were run by Nubian peoples outside Roman rule.[113]

Christianity became the dominant religion in the Roman Empire, including Egypt, during the fourth and fifth centuries CE. Egyptian temple cults died out, gradually and at various times, from a combination of lack of funds and Christian hostility.[114] Isis's temple at Philae, supported by its Nubian worshippers, still had an organized priesthood and regular festivals until at least the mid-fifth century CE, making it the last fully functioning temple in Egypt.[115][Note 5]

Funerary

In many spells in the Pyramid Texts, Isis and Nephthys help the deceased king reach the afterlife. In the Coffin Texts from the Middle Kingdom, Isis appears still more frequently, though in these texts Osiris is credited with reviving the dead more often than she is. New Kingdom sources such as the Book of the Dead describe Isis as protecting deceased souls as they face the dangers in the Duat. They also describe Isis as a member of the divine councils that judge souls' moral righteousness before admitting them into the afterlife, and she appears in vignettes standing beside Osiris as he presides over this tribunal.[117]

Isis and Nephthys took part in funeral ceremonies, where two wailing women, much like those in the festival at Abydos, mourned the deceased as the two goddesses mourned Osiris.[118] Isis was frequently shown or alluded to in funerary equipment: on sarcophagi and canopic chests as one of the four goddesses who protected the Four Sons of Horus, in tomb art offering her enlivening milk to the dead, and in the tyet amulets that were often placed on mummies to ensure that Isis's power would shield them from harm.[119] Late funerary texts prominently featured her mourning for Osiris, and one such text, one of the Books of Breathing, was said to have been written by her for Osiris's benefit.[120] In Nubian funerary religion, Isis was regarded as more significant than her husband, because she was the active partner while he only passively received the offerings she made to sustain him in the afterlife.[121]

Popular worship

Unlike many Egyptian deities, Isis was rarely addressed in prayers,[122] or invoked in personal names, before the end of the New Kingdom.[123] From the Late Period on, she became one of the deities most commonly mentioned in these sources, which often refer to her kindly character and her willingness to answer those who call upon her for help.[124] Hundreds of thousands of amulets and votive statues of Isis nursing Horus were made during the first millennium BCE,[125] and in Roman Egypt she was among the deities most commonly represented in household religious art, such as figurines and panel paintings.[126]

Isis was prominent in magical texts from the Middle Kingdom onward. The dangers Horus faces in childhood are a frequent theme in magical healing spells, in which Isis's efforts to heal him are extended to cure any patient. In many of these spells, Isis forces Ra to help Horus by declaring that she will stop the sun in its course through the sky unless her son is cured.[127] Other spells equated pregnant women with Isis to ensure that they would deliver their children successfully.[128]

Egyptian magic began to incorporate Christian concepts as Christianity was established in Egypt, but Egyptian and Greek deities continued to appear in spells long after their temple worship had ceased.[129] Spells that may date to the sixth, seventh, or eighth centuries CE invoke the name of Isis alongside Christian figures.[130]

In the Greco-Roman world

Spread

Cults based in a particular city or nation were the norm across the ancient world until the mid- to late first millennium BCE, when increased contact between different cultures allowed some cults to spread more widely. Greeks were aware of Egyptian deities, including Isis, at least as early as the Archaic Period (c. 700–480 BCE), and her first known temple in Greece was built during or before the fourth century BCE by Egyptians living in Athens. The conquests of Alexander the Great late in that century created Hellenistic kingdoms around the Mediterranean and Near East, including Ptolemaic Egypt, and put Greek and non-Greek religions in much closer contact. The resulting diffusion of cultures allowed many religious traditions to spread across the Hellenistic world in the last three centuries BCE. The new mobile cults adapted greatly to appeal to people from a variety of cultures. The cults of Isis and Serapis were among those that expanded in this way.[131]

Spread by merchants and other Mediterranean travelers, the cults of Isis and Serapis were established in Greek port cities at the end of the fourth century BCE and expanded throughout Greece and Asia Minor during the third and second centuries. The Greek island of Delos was an early cult center for both deities, and its status as a trading center made it a springboard for the Egyptian cults to diffuse into Italy.[132] Isis and Serapis were also worshipped at scattered sites in the Seleucid Empire, the Hellenistic kingdom in the Middle East, as far east as Iran, though they disappeared from the region as the Seleucids lost their eastern territory to the Parthian Empire.[133]

Greeks regarded Egyptian religion as exotic and sometimes bizarre, yet full of ancient wisdom.[134] Like other cults from the eastern regions of the Mediterranean, the cult of Isis attracted Greeks and Romans by playing upon its exotic origins,[135] but the form it took after reaching Greece was heavily Hellenized.[136]

Isis's cult reached Italy and the Roman sphere of influence at some point in the second century BCE.[137] It was one of many cults that were introduced to Rome as the Roman Republic's territory expanded in the last centuries BCE. Authorities in the Republic tried to define which cults were acceptable and which were not, as a way of defining Roman cultural identity amid the cultural changes brought on by Rome's expansion.[138] In Isis's case, shrines and altars to her were set up on the Capitoline Hill, at the heart of the city, by private persons in the early first century BCE.[137] The independence of her cult from the control of Roman authorities made it potentially unsettling to them.[139] In the 50s and 40s BCE, when the crisis of the Roman Republic made many Romans fear that peace among the gods was being disrupted, the Roman Senate destroyed these shrines,[140][141] although it did not ban Isis from the city outright.[137]

Egyptian cults faced further hostility during the Final War of the Roman Republic (32–30 BCE), when Rome, led by Octavian, the future emperor Augustus, fought Egypt under Cleopatra VII.[142] After Octavian's victory, he banned shrines to Isis and Serapis within the pomerium, the city's innermost, sacred boundary, but allowed them in parts of the city outside the pomerium, thus marking Egyptian deities as non-Roman but acceptable to Rome.[143] Despite being temporarily expelled from Rome during the reign of Tiberius (14–37 CE),[Note 6] the Egyptian cults gradually became an accepted part of the Roman religious landscape. The Flavian emperors in the late first century CE treated Serapis and Isis as patrons of their rule in much the same manner as traditional Roman deities such as Jupiter and Minerva.[145] Even as it was being integrated into Roman culture, Isis's worship developed new features that emphasized its Egyptian background.[146][147]

The cults also expanded into Rome's western provinces, beginning along the Mediterranean coast in early imperial times. At their peak in the late second and early third centuries CE, Isis and Serapis were worshipped in most towns across the western empire, though without much presence in the countryside.[148] Their temples were found from Petra and Palmyra, in the Arabian and Syrian provinces, to Italica in Spain and Londinium in Britain.[149] By this time they were on a comparable footing with native Roman deities.[150]

Roles

Isis's cult, like others in the Greco-Roman world, had no firm dogma, and its beliefs and practices may have stayed only loosely similar as it diffused across the region and evolved over time.[152][153] Greek aretalogies that praise Isis provide much of the information about these beliefs. Parts of these aretalogies closely resemble ideas in late Egyptian hymns like those at Philae, while other elements are thoroughly Greek.[154] Other information comes from Plutarch (c. 46–120 CE), whose book On Isis and Osiris interprets the Egyptian deities based on his Middle Platonist philosophy,[155] and from several works of Greek and Latin literature that refer to Isis's worship, especially a novel by Apuleius (c. 125–180 CE) known as Metamorphoses or The Golden Ass, which ends by describing how the main character has a vision of the goddess and becomes her devotee.[156]

Elaborating upon Isis's role as a wife and mother in the Osiris myth, aretalogies call her the inventor of marriage and parenthood. She was invoked to protect women in childbirth and, in ancient Greek novels such as the Ephesian Tale, to protect their virginity.[157] Some ancient texts called her the patroness of women in general.[158][159] Her cult may have served to promote women's autonomy in a limited way, with Isis's power and authority serving as a precedent, but in myth she was devoted to, and never fully independent of, her husband and son. The aretalogies show ambiguous attitudes toward women's independence: one says Isis made women equal to men, whereas another says she made women subordinate to their husbands.[160][161]

Isis was often characterized as a moon goddess, paralleling the solar characteristics of Serapis.[162] She was also seen as a cosmic goddess more generally. Various texts claim she organized the behavior of the sun, moon, and stars, governing time and the seasons which, in turn, guaranteed the fertility of the earth.[163] These texts also credit her with inventing agriculture, establishing laws, and devising or promoting other elements of human society. This idea derives from older Greek traditions about the role of various Greek deities and culture heroes, including Demeter, in establishing civilization.[164]

She also oversaw seas and harbors. Sailors left inscriptions calling upon her to ensure the safety and good fortune of their voyages. In this role she was called Isis Pelagia, "Isis of the Sea", or Isis Pharia, referring to a sail or to the island of Pharos, site of the Lighthouse of Alexandria.[165] This form of Isis, which emerged in Hellenistic times, may have been inspired by Egyptian images of Isis in a barque, as well as by Greek deities who protected seafaring, such as Aphrodite.[166][167] Isis Pelagia developed an added significance in Rome. Rome's food supply was dependent on grain shipments from its provinces, especially Egypt. Isis therefore guaranteed fertile harvests and protected the ships that carried the resulting food across the seas—and thus ensured the well-being of the empire as a whole.[168] Her protection of the state was said to extend to Rome's armies, much as it was in Ptolemaic Egypt, and she was sometimes called Isis Invicta, "Unconquered Isis".[169] Her roles were so numerous that she came to be called myrionymos, "one with countless names," and panthea, "all-goddess".[170]

Both Plutarch and a later philosopher, Proclus, mentioned a veiled statue of the Egyptian goddess Neith, whom they conflated with Isis, citing it as an example of her universality and enigmatic wisdom. It bore the words "I am all that has been and is and will be; and no mortal has ever lifted my mantle."[171][Note 7]

Isis was also said to benefit her followers in the afterlife, which was not much emphasized in Greek and Roman religion.[174] The Golden Ass and inscriptions left by worshippers of Isis suggest that many of her followers thought she would guarantee them a better afterlife in return for their devotion. They characterized this afterlife inconsistently. Some said they would benefit from Osiris's enlivening water while others expected to sail to the Fortunate Isles of Greek tradition.[175]

As in Egypt, Isis was said to have power over fate, which in traditional Greek religion was a power not even the gods could defy. Valentino Gasparini says this control over destiny binds together Isis's disparate traits. She governs the cosmos, yet she also relieves people of their comparatively trivial misfortunes, and her influence extends into the realm of death, which is "individual and universal at the same time".[176]

Relationships with other deities

More than a dozen Egyptian deities were worshipped outside Egypt in Hellenistic and Roman times in a series of interrelated cults, though many were fairly minor.[177] Of the most important of these deities, Serapis was closely connected with Isis and often appeared with her in art, but Osiris remained central to her myth and prominent in her rituals.[178] Temples to Isis and Serapis sometimes stood next to each other, but it was rare for a single temple to be dedicated to both.[179] Osiris, as a dead deity unlike the immortal gods of Greece, seemed strange to Greeks and played only a minor role in Egyptian cults in Hellenistic times. In Roman times he became, like Dionysus, a symbol of a joyous afterlife, and the Isis cult increasingly focused on him.[180] Horus, often under the name Harpocrates, also appeared in Isis's temples as her son by Osiris or Serapis. He absorbed traits from Greek deities such as Apollo and served as a god of the sun and of crops.[181] Another member of the group was Anubis, who was linked to the Greek god Hermes in his Hellenized form Hermanubis.[182] Isis was also sometimes said to have learned her wisdom from, or even be the daughter of, Thoth, the Egyptian god of writing and knowledge, who was known in the Greco-Roman world as Hermes Trismegistus.[183][184]

Isis also had an extensive network of connections with Greek and Roman deities, as well as some from other cultures. She was not fully integrated into the Greek pantheon, but she was at different times equated with a variety of Greek mythological figures, including Demeter, Aphrodite, or Io, a human woman who was turned into a cow and chased by the goddess Hera from Greece to Egypt.[185] The cult of Demeter was an especially important influence on Isis's worship after its arrival in Greece.[186] Isis's relationship with women was influenced by her frequent equation with Artemis, who had a dual role as a virgin goddess and a promoter of fertility.[187] Because of Isis's power over fate, she was linked with the Greek and Roman personifications of fortune, Tyche and Fortuna.[188] At Byblos in Phoenicia in the second millennium BCE, Hathor had been worshipped as a form of the local goddess Baalat Gebal. Isis gradually replaced Hathor there in the course of the first millennium BCE[189] and became syncretized with another goddess from the region, Astarte.[190] In Noricum in central Europe, Isis was syncretized with the local tutelary deity Noreia,[191] and at Petra she may have been linked with the Arab goddess al-Uzza.[192] The Roman author Tacitus said Isis was worshipped by the Suebi, a Germanic people living outside the empire, but he may have mistaken a Germanic goddess for Isis because, like her, the goddess was symbolized by a ship.[193]

Many of the aretalogies include long lists of goddesses with whom Isis was linked. These texts treat all the deities they list as forms of her, suggesting that in the eyes of the authors she was a summodeistic being: the one goddess for the entire civilized world.[194][195] In the Roman religious world, many deities were referred to as "one" or "unique" in religious texts like these. At the same time, Hellenistic philosophers frequently saw the unifying, abstract principle of the cosmos as divine. Many of them reinterpreted traditional religions to fit their concept of this highest being, as Plutarch did with Isis and Osiris.[196] In The Golden Ass Isis says "my one person manifests the aspects of all the gods and goddesses" and that she is "worshipped by all the world under different forms, with various rites, and by manifold names," although the Egyptians and Nubians use her true name, Isis.[197][198] But when she lists the forms in which various Mediterranean peoples worship her, she mentions only female deities.[199] Greco-Roman deities were firmly divided by gender, thus limiting how universal Isis could truly be. One aretalogy avoids this problem by calling Isis and Serapis, who was often said to subsume many male gods, the two "unique" deities.[200][201] Similarly, both Plutarch and Apuleius limit Isis's importance by treating her as ultimately subordinate to Osiris.[202] The claim that she was unique was meant to emphasize her greatness more than to make a precise theological statement.[200][201]

Iconography

Images of Isis made outside Egypt were Hellenistic in style, like many of the images of her made in Egypt in Hellenistic and Roman times. The attributes she bore varied widely.[203] She sometimes wore the Hathoric cow-horn headdress, but Greeks and Romans reduced its size and often interpreted it as a crescent moon.[204] She could also wear headdresses incorporating leaves, flowers, or ears of grain.[205] Other common traits included corkscrew locks of hair and an elaborate mantle tied in a large knot over the breasts, which originated in ordinary Egyptian clothing but was treated as a symbol of the goddess outside Egypt.[206][Note 8] In her hands she could carry a uraeus or a sistrum, both taken from her Egyptian iconography,[208] or a situla, a vessel used for libations of water or milk that were performed in Isis's cult.[209]

As Isis-Fortuna or Isis-Tyche she held a rudder, representing control of fate, in her right hand and a cornucopia, standing for abundance, in her left.[210] As Isis Pharia she wore a cloak that billowed behind her like a sail, and as Isis Lactans, she nursed Harpocrates.[211] At times she was shown resting a foot on a celestial sphere, representing her control of the cosmos.[212] The diverse imagery sprang from her varied roles; as Robert Steven Bianchi says, "Isis could represent anything to anyone and could be represented in any way imaginable."[213]

- Statue of Isis-Persephone with corkscrew locks of hair and a sistrum, from Gortyna, second century CE

- Isis-Aphrodite, polychrome terracotta, Alexandria, first century CE

- Bronze figurine of Isis-Fortuna with a cornucopia and a rudder, first century CE

- Fresco of Isis wearing a crescent headdress and resting her foot on a celestial sphere, first century CE

Worship

Adherents and priests

Like most cults of the time, the Isis cult did not require its devotees to worship Isis exclusively, and their level of commitment probably varied greatly.[214] Some devotees of Isis served as priests in a variety of cults and underwent several initiations dedicated to different deities.[215] Nevertheless, many emphasized their strong devotion to her, and some considered her the focus of their lives.[216] They were among the very few religious groups in the Greco-Roman world to have a distinctive name for themselves, loosely equivalent to "Jew" or "Christian", that might indicate they defined themselves by their religious affiliation. However, the word—Isiacus or "Isiac"—was rarely used.[214]

Isiacs were a very small proportion of the Roman Empire's population,[217] but they came from every level of society, from slaves and freedmen to high officials and members of the imperial family.[218] Ancient accounts imply that Isis was popular with lower social classes, providing a possible reason why authorities in the Roman Republic, troubled by struggles between classes, regarded her cult with suspicion.[219] Women were more strongly represented in the Isis cult than in most Greco-Roman cults, and in imperial times, they could serve as priestesses in many of the same positions in the hierarchy as their male counterparts.[220] Women make up much less than half of the Isiacs known from inscriptions and are rarely listed among the higher ranks of priests,[221] but because women are underrepresented in Roman inscriptions, their participation may have been greater than is recorded.[222] Several Roman writers accused Isis's cult of encouraging promiscuity among women. Jaime Alvar suggests the cult attracted male suspicion simply because it gave women a venue to act outside their husbands' control.[223]

Priests of Isis were known for their distinctive shaven heads and white linen clothes, both characteristics drawn from Egyptian priesthoods and their requirements of ritual purity.[224] A temple of Isis could include several ranks of priests, as well as various cultic associations and specialized duties for lay devotees.[225] There is no evidence of a hierarchy overseeing multiple temples, and each temple may well have functioned independently of the others.[226]

Temples and daily rites

Temples to Egyptian deities outside Egypt, such as the Red Basilica in Pergamon, the Temple of Isis at Pompeii, or the Iseum Campense in Rome, were built in a largely Greco-Roman style but, like Egyptian temples, were surrounded by large courts enclosed by walls. They were decorated with Egyptian-themed artwork, sometimes including antiquities imported from Egypt. Their layout was more elaborate than that of traditional Roman temples and included rooms for housing priests and for various ritual functions, with a cult statue of the goddess in a secluded sanctuary.[228][229] Unlike Egyptian cult images, Isis's Hellenistic and Roman statues were life-size or larger. The daily ritual still entailed dressing the statue in elaborate clothes each morning and offering it libations, but in contrast with Egyptian tradition, the priests allowed ordinary devotees of Isis to see the cult statue during the morning ritual, pray to it directly, and sing hymns before it.[230]

Another object of veneration in these temples was water, which was treated as a symbol of the waters of the Nile. Isis temples built in Hellenistic times often included underground cisterns that stored this sacred water, raising and lowering the water level in imitation of the Nile flood. Many Roman temples instead used a pitcher of water that was worshipped as a cult image or manifestation of Osiris.[231]

Personal worship

Roman lararia, or household shrines, contained statuettes of the penates, a varied group of protective deities chosen based on the preferences of the members of the household.[232] Isis and other Egyptian deities were found in lararia in Italy from the late first century BCE[233] to the beginning of the fourth century CE.[234]

The cult asked both ritual and moral purity of its devotees, periodically requiring ritual baths or days-long periods of sexual abstinence. Isiacs sometimes displayed their piety on irregular occasions, singing Isis's praises in the streets or, as a form of penance, declaring their misdeeds in public.[235]

Some temples to Greek deities, including Serapis, practiced incubation, in which worshippers slept in a temple hoping that the god would appear to them in a dream and give them advice or heal their ailments. Some scholars believe that this practice took place in Isis's temples, but there is no firm evidence that it did.[236] Isis was, however, thought to communicate through dreams in other circumstances, including to call worshippers to undergo initiation.[237]

Initiation

Some temples of Isis performed mystery rites to initiate new members of the cult. These rites were claimed to be of Egyptian origin and may have drawn on the secretive tendencies of some Egyptian rites.[238] However, they were mainly based on Greek mystery cults, especially the Eleusinian mysteries dedicated to Demeter, colored with Egyptian elements.[239][240][Note 9] Although mystery rites are among the best-known elements of Isis's Greco-Roman cult, they are only known to have been performed in Italy, Greece, and Asia Minor.[243] By giving the devotee a dramatic, mystical experience of the goddess, initiations added emotional intensity to the process of joining her following.[237]

The Golden Ass, in describing how the protagonist joins Isis's cult, gives the only detailed account of Isiac initiation.[245] Apuleius's motives for writing about the cult and the accuracy of his fictionalized description are much debated. But the account is broadly consistent with other evidence about initiations, and scholars rely heavily on it when studying the subject.[246]

Ancient mystery rites used a variety of intense experiences, such as nocturnal darkness interrupted by bright light and loud music and noise, to overwhelm their senses and give them an intense religious experience that felt like direct contact with the god they devoted themselves to.[247] Apuleius's protagonist, Lucius, undergoes a series of initiations, though only the first is described in detail. After entering the innermost part of Isis's temple at night, he says, "I came to the boundary of death and, having trodden on the threshold of Proserpina, I travelled through all the elements and returned. In the middle of the night I saw the sun flashing with bright light, I came face to face with the gods below and the gods above and paid reverence to them from close at hand."[248] This cryptic description suggests that the initiate's symbolic journey to the world of the dead was likened to Osiris's rebirth, as well as to Ra's journey through the underworld in Egyptian myth,[249] possibly implying that Isis brought the initiate back from death as she did her husband.[250]

Festivals

Roman calendars listed the two most important festivals of Isis as early as the first century CE. The first festival was the Navigium Isidis in March, which celebrated Isis's influence over the sea and served as a prayer for the safety of seafarers and, eventually, of the Roman people and their leaders.[251] It consisted of an elaborate procession, including Isiac priests and devotees with a wide variety of costumes and sacred emblems, carrying a model ship from the local Isis temple to the sea[252] or to a nearby river.[253] The other was the Isia in late October and early November. Like its Egyptian forerunner, the Khoiak festival, the Isia included a ritual reenactment of Isis's search for Osiris, followed by jubilation when the god's body was found.[254] Several more minor festivals were dedicated to Isis, including the Pelusia in late March that may have celebrated the birth of Harpocrates, and the Lychnapsia, or lamp-lit festival, that celebrated Isis's own birth on August 12.[251]

Festivals of Isis and other polytheistic deities were celebrated throughout the fourth century CE, despite the growth of Christianity in that era and the persecution of pagans that intensified toward the end of the century.[255] The Isia was celebrated at least as late as 417 CE,[256] and the Navigium Isidis lasted well into the sixth century.[257] Increasingly, the religious meaning of all Roman festivals was forgotten or ignored even as the customs continued. In some cases, these customs became part of the combined classical and Christian culture of the Early Middle Ages.[258]

Possible influence on Christianity

A contentious question about Isis is whether her cult influenced Christianity.[259] Some Isiac customs may have been among the pagan religious practices that were incorporated into Christian traditions as the Roman Empire was Christianized. Andreas Alföldi, for instance, argued in the 1930s that the medieval Carnival festival, in which a model boat was carried, developed from the Navigium Isidis.[260]

Much attention focuses on whether traits of Christianity were borrowed from pagan mystery cults, including that of Isis.[261] The more devoted members of Isis's cult made a personal commitment to a deity they regarded as superior to others, as Christians did.[262] Both Christianity and the Isis cult had an initiation rite: the mysteries for Isis, baptism in Christianity.[263] One of the mystery cults' shared themes—a god whose death and resurrection may be connected with the individual worshipper's well-being in the afterlife—resembles the central theme of Christianity. The suggestion that Christianity's basic beliefs were taken from mystery cults has provoked heated debate for more than 200 years.[264] In response to these controversies, both Hugh Bowden and Jaime Alvar, scholars who study ancient mystery cults, suggest that similarities between Christianity and the mystery cults were not produced by direct borrowing of ideas but by their common background: the Greco-Roman culture in which they all developed.[263][265]

Similarities between Isis and Mary, the mother of Jesus, have also been scrutinized. They have been subject to controversy between Protestant Christians and the Catholic Church, as many Protestants have argued that Catholic veneration of Mary is a remnant of paganism.[266] The classicist R. E. Witt saw Isis as the "great forerunner" of Mary. He suggested that converts to Christianity who had formerly worshipped Isis would have seen Mary in much the same terms as their traditional goddess. He pointed out that the two had several spheres of influence in common, such as agriculture and the protection of sailors. He compared Mary's title "Mother of God" to Isis's epithet "mother of the god", and Mary's "queen of heaven" to Isis's "queen of heaven".[267] Stephen Benko, a historian of early Christianity, argues that devotion to Mary was deeply influenced by the worship of several goddesses, not just Isis.[268] In contrast, John McGuckin, a church historian, says that Mary absorbed superficial traits from these goddesses, such as iconography, but the fundamentals of her cult were thoroughly Christian.[269]

Images of Isis with Horus in her lap are often suggested as an influence on the iconography of Mary, particularly images of the Mary nursing the infant Jesus, as images of nursing women were rare in the ancient Mediterranean world outside Egypt.[270] Vincent Tran Tam Tinh points out that the latest images of Isis nursing Horus date to the fourth century CE, while the earliest images of Mary nursing Jesus date to the seventh century CE. Sabrina Higgins, drawing on his study, argues that if there is a connection between the iconographies of Isis and Mary, it is limited to images from Egypt.[271] In contrast, Thomas F. Mathews and Norman Muller think Isis's pose in late antique panel paintings influenced several types of Marian icons, inside and outside Egypt.[272] Elizabeth Bolman says these early Egyptian images of Mary nursing Jesus were meant to emphasize his divinity, much as images of nursing goddesses did in ancient Egyptian iconography.[273] Higgins argues that such similarities prove that images of Isis influenced those of Mary, but not that Christians deliberately adopted Isis's iconography or other elements of her cult.[274]

Influence in later cultures

The memory of Isis survived the extinction of her worship. Like the Greeks and Romans, many modern Europeans have regarded ancient Egypt as the home of profound and often mystical wisdom, and this wisdom has often been linked with Isis.[275] Giovanni Boccaccio's biography of Isis in his 1374 work De mulieribus claris, based on classical sources, treated her as a historical queen who taught skills of civilization to humankind. Some Renaissance thinkers elaborated this perspective on Isis. Annio da Viterbo, in the 1490s, claimed Isis and Osiris had civilized Italy before Greece, thus drawing a direct connection between his home country and Egypt. The Borgia Apartments painted for Annio's patron, Pope Alexander VI, incorporate this same theme in their illustrated rendition of the Osiris myth.[276]

Western esotericism has often made reference to Isis. Two Roman esoteric texts used the mythic motif in which Isis passes down secret knowledge to Horus. In Kore Kosmou, she teaches him wisdom passed down from Hermes Trismegistus,[277] and in the early alchemical text Isis the Prophetess to Her Son Horus, she gives him alchemical recipes.[278] Early modern esoteric literature, which saw Hermes Trismegistus as an Egyptian sage and frequently made use of texts attributed to his hand, sometimes referred to Isis as well.[279] In a different vein, Apuleius's description of Isiac initiation has influenced the practices of many secret societies.[280] Jean Terrasson's 1731 novel Sethos used Apuleius as inspiration for a fanciful Egyptian initiation rite dedicated to Isis.[281] It was imitated by actual rituals in various Masonic and Masonic-inspired societies during the eighteenth century, as well as in other literary works, most notably Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's 1791 opera The Magic Flute.[282]

From the Renaissance on, the veiled statue of Isis that Plutarch and Proclus mentioned was interpreted as a personification of nature, based on a passage in the works of Macrobius in the fifth century CE that equated Isis with nature.[283][Note 10] Authors in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries ascribed a wide variety of meanings to this image. Isis represented nature as the mother of all things, as a set of truths waiting to be unveiled by science, as a symbol of the pantheist concept of an anonymous, enigmatic deity who was immanent within nature,[284] or as an awe-inspiring sublime power that could be experienced through ecstatic mystery rites.[285] In the dechristianization of France during the French Revolution, she served as an alternative to traditional Christianity: a symbol that could represent nature, modern scientific wisdom, and a link to the pre-Christian past.[286] For these reasons, Isis's image appeared in artwork sponsored by the revolutionary government, such as the Fontaine de la Régénération, and by the First French Empire.[287][288] The metaphor of Isis's veil continued to circulate through the nineteenth century. Helena Blavatsky, the founder of the esoteric Theosophical tradition, titled her 1877 book on Theosophy Isis Unveiled, implying that it would reveal spiritual truths about nature that science could not.[289]

Among modern Egyptians, Isis was used as a national symbol during the Pharaonism movement of the 1920s and 1930s, as Egypt gained independence from British rule. In works such as Mohamed Naghi's painting in the parliament of Egypt, titled Egypt's Renaissance, and Tawfiq al-Hakim's play The Return of the Spirit, Isis symbolizes the revival of the nation. A sculpture by Mahmoud Mokhtar, also called Egypt's Renaissance, plays upon the motif of Isis's removing her veil.[290]

Isis is found frequently in works of fiction, such as a superhero franchise, and her name and image appear in places as disparate as advertisements and personal names.[291] The name Isidoros, meaning "gift of Isis" in Greek,[292] survived in Christianity despite its pagan origins, giving rise to the English name Isidore and its variants.[293] In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, "Isis" itself became a popular feminine given name.[294]

Isis continues to appear in modern esoteric and pagan belief systems. The concept of a single goddess incarnating all feminine divine powers, partly inspired by Apuleius, became a widespread theme in literature of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[295] Influential groups and figures in esotericism, such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in the late nineteenth century and Dion Fortune in the 1930s, adopted this all-encompassing goddess into their belief systems and called her Isis. This conception of Isis influenced the Great Goddess found in many forms of Neopagan witchcraft.[296][297] Today, reconstructions of ancient Egyptian religion, such as Kemetic Orthodoxy[298] or the Church of the Eternal Source, include Isis among the deities they revere.[299] An eclectic religious organization focused on female divinity calls itself the Fellowship of Isis because, in the words of one of its priestesses, M. Isidora Forrest, Isis can be "all Goddesses to all people".[300]

See also

Notes

- ^ Ancient Egyptian: 𓊨𓏏𓆇𓁐, romanized: ꜣst;[2] Coptic: Ⲏⲥⲉ Ēse; Classical Greek: Ἶσις; Meroitic: 𐦥𐦣𐦯 Wos[a] or Wusa; Phoenician: 𐤀𐤎,[4] romanized: ʾs

- ^ The worship of a particular god, such as Isis, within ancient Egyptian religion is termed a "cult".[10] The same is often true for the worship of individual gods within Greek or Roman religion. Classicists sometimes refer to the veneration of Isis, or of certain other deities who were introduced to the Greco-Roman world, as "religions" because they were more distinct from the culture around them than the cults of Greek or Roman gods.[11] However, these cults did not form the kind of independent, self-contained communities with distinct worldviews that Jewish and Christian groups in the Roman Empire did.[12] Françoise Dunand and Jaime Alvar have both argued that the worship of Isis should be called a "cult", because it formed a part of the wider systems of Greek and Roman religion, rather than an independent, all-encompassing system of beliefs like Judaism or Christianity.[11][13]

- ^ Originally the first consonant in the name, ꜣ, was pronounced as r or l. By the time of the New Kingdom it had weakened to a glottal stop sound, and the t at the end of words had disappeared from speech, so in the New Kingdom the pronunciation of Isis's name was similar to Usa. Forms of her name in other languages all descend from this pronunciation.[14] The Meroitic forms of her name, 𐦥𐦣𐦯 Wos[a] or 𐦠𐦯 As[a], indicate the pronunciation /uːɕa/.[3]

- ^ These figurines, which were common in Roman Egypt, are often thought to depict Isis or Hathor combined with Aphrodite, but it is not even certain that they represent a goddess.[83] The exposed genitals may represent fertility[82] or be meant to ward off evil.[83]

- ^ Scholars have traditionally believed, based on the writings of Procopius, that Philae was closed in about AD 535 by a military expedition under Justinian I. Jitse Dijkstra has argued that Procopius's account of the temple closure is inaccurate and that regular religious activity there ceased shortly after the last date inscribed at the temple, in 456 or 457 CE.[115] Eugene Cruz-Uribe suggests instead that during the fifth and sixth centuries the temple lay empty most of the time, but Nubians living nearby continued to hold periodic festivals there until well into the sixth century.[116]

- ^ Tiberius's expulsion of the Egyptian cults was part of a broader reaction against religious practices that were regarded as a threat to order and tradition, including Judaism and astrology. Josephus, a Roman-Jewish historian who gives the most detailed account of the expulsion, says the Egyptian cults were targeted because of a scandal in which a man posed as Anubis, with the help of Isis's priests, in order to seduce a Roman noblewoman. Sarolta Takács casts doubt on Josephus's account, arguing that it is fictionalized in order to convey a moral point.[144]

- ^ The statue was at a temple in Sais, Neith's cult center. She was largely conflated with Isis in Plutarch's time, and he says the statue is of "Athena [Neith], whom [the Egyptians] consider to be Isis". Proclus' version of the quotation says "no one has ever lifted my veil," implying that the goddess is virginal.[172] This claim was occasionally made of Isis in Greco-Roman times, though it conflicted with the widespread belief that she and Osiris together conceived Horus.[173] Proclus also adds "The fruit of my womb was the sun", suggesting that the goddess conceived and gave birth to the sun without the participation of a male deity, which would mean it referred to Egyptian myths about Neith as the mother of Ra.[172]

- ^ This knot is sometimes called the "Isis-knot", although it should not be confused with the tyet symbol, which is also sometimes called the "knot of Isis".[207]

- ^ The mystery rites may have emerged as part of the Hellenization of Isis under the Ptolemies in the third century BCE,[241] in Greece under the influence of the cult of Demeter in the first century BCE,[242] or as late as the first or second century CE.[243] Even after the initiation ceremony had developed, few texts in Egypt referred to it.[244]

- ^ Early modern illustrations of Isis as nature often showed her with multiple breasts. Originally, the form of Artemis that was worshipped at Ephesus was depicted with round protuberances on her chest that came to be interpreted as breasts. Early modern artists drew Isis in this form because Macrobius claimed that both Isis and Artemis were depicted this way.[283]

References

Citations

- ^ Hart 2005, p. 79.

- ^ a b c d Quack 2018, p. 108.

- ^ a b Rilly & de Vogt 2012, p. 37.

- ^ CIS I 308; RÉS 367.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, pp. 12–14, 146.

- ^ Griffiths 1980, p. 41.

- ^ Münster 1968, p. 159.

- ^ Pinch 2002, pp. 9–11.

- ^ Münster 1968, p. 158.

- ^ Teeter 2001, p. 340.

- ^ a b Alvar 2008, pp. 2–4.

- ^ Burkert 1987, pp. 51–53.

- ^ Dunand 2010, pp. 40–41, 50–51.

- ^ a b Quack 2018, pp. 108–109.

- ^ a b Griffiths 1980, pp. 91, 95–97.

- ^ Frankfort 1978, pp. 43–44, 108.

- ^ Kuhlmann 2011, p. 2.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, p. 119.

- ^ a b Vinson 2008, pp. 313–316.

- ^ Dunand & Zivie-Coche 2004, pp. 235–237.

- ^ Pinch 2002, pp. 66, 68, 76–78.

- ^ a b Pinch 2002, pp. 79–80, 178–179.

- ^ Pinch 2002, pp. 80, 150.

- ^ Assmann 2005, pp. 32–36, 115–118.

- ^ Smith 2009, pp. 54–55, 97–99.

- ^ Assmann 2001, pp. 129–131, 144–145.

- ^ a b Cooney 2010, pp. 227–228.

- ^ Assmann 2005, pp. 151–154.

- ^ Cooney 2010, pp. 235–236.

- ^ Smith 2009, pp. 119, 141.

- ^ Venit 2010, pp. 98, 107.

- ^ Smith 2017, p. 386.

- ^ Lesko 1999, pp. 158–159.

- ^ a b Griffiths 1980, pp. 14–17.

- ^ Griffiths 1970, pp. 300–301.

- ^ Pinch 2002, p. 149.

- ^ Pinch 2002, pp. 80–81, 146.

- ^ Meeks & Favard-Meeks 1996, pp. 82, 86–87.

- ^ Lesko 1999, p. 182.

- ^ Lesko 1999, p. 176.

- ^ Griffiths 2001, p. 189.

- ^ Pinch 2002, p. 145.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, p. 115.

- ^ Traunecker 2001, pp. 221–222.

- ^ a b c d Münster 1968, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Griffiths 1960, pp. 48–50.

- ^ Meeks & Favard-Meeks 1996, p. 67.

- ^ Smith 2017, p. 393.

- ^ Pinch 2002, p. 115.

- ^ Lesko 1999, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Meeks & Favard-Meeks 1996, pp. 185–186.

- ^ a b Vanderlip 1972, pp. 93–96.

- ^ Lesko 1999, pp. 159, 170.

- ^ Assmann 2001, p. 134.

- ^ a b Troy 1986, pp. 68–70.

- ^ a b Žabkar 1988, pp. 60–62, 72.

- ^ Žabkar 1988, pp. 73–74, 81–82.

- ^ a b Pinch 2002, p. 151.

- ^ Meeks & Favard-Meeks 1996, p. 98.

- ^ a b c Hart 2005, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Baines 1996, p. 371.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, p. 147.

- ^ Griffiths 1980, pp. 12–14, 157–158.

- ^ Žabkar 1988, p. 114.

- ^ Tobin 2001, p. 466.

- ^ Žabkar 1988, pp. 43–44, 81–82.

- ^ Delia 1998, pp. 546–547.

- ^ a b c d e Žabkar 1988, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Žabkar 1988, pp. 42–44, 67.

- ^ Assmann 1997, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Assmann 2001, pp. 240–242.

- ^ Wente 2001, pp. 433–434.

- ^ Smith 2010, p. 169.

- ^ McClain 2011, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Pinch 2002, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Frankfurter 1998, pp. 99–102.

- ^ a b c d Wilkinson 2003, pp. 148–149, 160.

- ^ Griffiths 1980, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Frankfurter 1998, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Bianchi 2007, pp. 493–494.

- ^ a b Frankfurter 1998, p. 104.

- ^ a b Sandri 2012, pp. 637–638.

- ^ Hart 2005, p. 80.

- ^ Andrews 2001, p. 80.

- ^ Frankfort 1978, pp. 43–44, 123, 137

- ^ Lesko 1999, p. 170

- ^ Troy 1986, p. 70

- ^ Bricault & Versluys 2014, pp. 30–31

- ^ Morkot 2012, pp. 121–122, 124

- ^ Pfeiffer 2008, pp. 387–388

- ^ Thompson 1998, pp. 699, 704–707

- ^ Solmsen 1979, pp. 56–57

- ^ Pfeiffer 2008, pp. 391–392, 400–403

- ^ Plantzos 2011, pp. 389–396

- ^ Münster 1968, pp. 189–190

- ^ Lesko 1999, p. 169

- ^ Münster 1968, pp. 165–166

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, p. 149

- ^ Dijkstra 2008, pp. 186–187

- ^ Dunand & Zivie-Coche 2004, pp. 236–237, 242

- ^ Dijkstra 2008, pp. 133, 137, 206–208

- ^ Yellin 2012a, p. 245

- ^ Yellin 2012b, pp. 133

- ^ Dunand & Zivie-Coche 2004, pp. 89–91

- ^ a b Dunand & Zivie-Coche 2004, pp. 300–301

- ^ Naerebout 2007, pp. 541, 547

- ^ Dunand & Zivie-Coche 2004, p. 93

- ^ Assmann 2005, p. 363

- ^ a b Lesko 1999, pp. 172–174

- ^ Smith 2009, pp. 96–98, 103

- ^ Frankfurter 1998, pp. 56, 61, 103–104

- ^ Dijkstra 2008, pp. 202–210

- ^ Frankfurter 1998, pp. 18–20, 26–27

- ^ a b Dijkstra 2008, pp. 342–347

- ^ Cruz-Uribe 2010, pp. 504–506

- ^ Lesko 1999, pp. 163–164, 166–168

- ^ Hays 2010, pp. 4–5

- ^ Lesko 1999, pp. 175, 177–179

- ^ Smith 2009, pp. 54–55, 462

- ^ Yellin 2012b, p. 137

- ^ Dunand & Zivie-Coche 2004, p. 137

- ^ Kockelmann 2008, p. 73

- ^ Kockelmann 2008, pp. 38–40, 81

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, p. 146

- ^ Mathews & Muller 2005, pp. 5–6

- ^ Pinch 2006, pp. 29, 144–146

- ^ Pinch 2006, pp. 128–129

- ^ Meyer 1994, pp. 27–29

- ^ Frankfurter 2009, pp. 230–231

- ^ Woolf 2014, pp. 73–79.

- ^ Bommas 2012, pp. 428–429.

- ^ Ma 2014, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Hornung 2001, pp. 19–25.

- ^ Bremmer 2014, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Bommas 2012, pp. 431–432.

- ^ a b c Versluys 2004, pp. 443–447.

- ^ Orlin 2010, pp. 3–7.

- ^ Beard, North & Price 1998, p. 161.

- ^ Takács 1995, pp. 64–67.

- ^ Orlin 2010, pp. 204–207.

- ^ Donalson 2003, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Orlin 2010, p. 211.

- ^ Takács 1995, pp. 83–86.

- ^ Donalson 2003, pp. 138–139, 159–162.

- ^ Wild 1981, pp. 149–151.

- ^ Bommas 2012, p. 431.

- ^ Bricault 2000, p. 206.

- ^ Bricault 2001, pp. 174–179.

- ^ Donalson 2003, pp. 177, 180–182.

- ^ Tiradritti 2005, pp. 21, 212.

- ^ Beard, North & Price 1998, pp. 248–249, 301–303.

- ^ Alvar 2008, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Žabkar 1988, pp. 135–137, 159–160.

- ^ Alvar 2008, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Donalson 2003, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Heyob 1975, pp. 48–50, 66–70.

- ^ Heyob 1975, p. 53.

- ^ Kraemer 1992, p. 74.

- ^ Kraemer 1992, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Alvar 2008, pp. 190–192.

- ^ Sfameni Gasparro 2007, p. 43.

- ^ Pachis 2010, pp. 307–313.

- ^ Solmsen 1979, pp. 34–35, 40–43.

- ^ Donalson 2003, pp. 68, 74–75.

- ^ Alvar 2008, pp. 296–300.

- ^ Legras 2014, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Pachis 2010, pp. 283–286.

- ^ Donalson 2003, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Donalson 2003, p. 10.

- ^ Griffiths 1970, pp. 131, 284–285.

- ^ a b Assmann 1997, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Griffiths 1970, p. 284.

- ^ Beard, North & Price 1998, pp. 289–290.

- ^ Gasparini 2016, pp. 135–137.

- ^ Gasparini 2011, pp. 700, 716–717.

- ^ Versluys 2007, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Takács 1995, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Renberg 2017, p. 331.

- ^ Bommas 2012, pp. 425, 430–431.

- ^ Witt 1997, pp. 210–212.

- ^ Witt 1997, pp. 198–203.

- ^ Witt 1997, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Griffiths 1970, p. 263.

- ^ Solmsen 1979, pp. 16–19, 53–57.

- ^ Pakkanen 1996, pp. 91, 94–100.

- ^ Heyob 1975, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Donalson 2003, p. 8.

- ^ Hollis 2009, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Griffiths 1970, p. 326.

- ^ Woolf 2014, p. 84.

- ^ Lahelma & Fiema 2008, pp. 209–211.

- ^ Rives 1999, pp. 80, 162.

- ^ Sfameni Gasparro 2007, pp. 54–56.

- ^ Smith 2010, pp. 243–246.

- ^ Van Nuffelen 2010, pp. 17–21, 26–27.

- ^ Hanson 1989, p. 299.

- ^ Griffiths 1975, pp. 154–155.

- ^ Griffiths 1975, pp. 143–144.

- ^ a b Versnel 2011, pp. 299–301.

- ^ a b Belayche 2010, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Gasparini 2011, pp. 706–708.

- ^ Bianchi 2007, pp. 480–482, 494.

- ^ Delia 1998, pp. 542–543.

- ^ Griffiths 1975, pp. 124–126.

- ^ Walters 1988, pp. 5–7.

- ^ Bianchi 1980, p. 10.

- ^ Griffiths 1975, pp. 132–135.

- ^ Walters 1988, pp. 20–25.

- ^ Donalson 2003, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Donalson 2003, pp. 6–7, 74.

- ^ Pachis 2010, pp. 305–306.

- ^ Bianchi 2007, p. 494.

- ^ a b Beard, North & Price 1998, pp. 236, 307–309.

- ^ Burkert 1987, pp. 46–50.

- ^ Bøgh 2015, pp. 279–282.

- ^ Alvar 2008, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Takács 1995, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Orlin 2010, p. 206.

- ^ Heyob 1975, p. 87.

- ^ Heyob 1975, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Kraemer 1992, p. 76.

- ^ Alvar 2008, pp. 183–184.

- ^ Donalson 2003, p. 49.

- ^ Heyob 1975, pp. 93–94, 103–105.

- ^ Bowden 2010, p. 177.

- ^ Witt 1997, p. 117.

- ^ Bommas 2012, p. 430.

- ^ Turcan 1996, pp. 104–109.

- ^ Donalson 2003, pp. 34–35, 39.

- ^ Wild 1981, pp. 60–61, 154–157.

- ^ Bodel 2008, pp. 258, 261–262.

- ^ Alvar 2008, p. 192.

- ^ Bodel 2008, p. 261.

- ^ Bøgh 2015, pp. 281–282.

- ^ Renberg 2017, pp. 392–393.

- ^ a b Bøgh 2015, p. 278.

- ^ Griffiths 1970, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Burkert 1987, p. 41.

- ^ Bremmer 2014, p. 116.

- ^ Alvar 2008, pp. 58–61.

- ^ Pakkanen 1996, pp. 78–82.

- ^ a b Bremmer 2014, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Venit 2010, p. 90.

- ^ Burkert 1987, p. 97.

- ^ Bowden 2010, pp. 165–167, 179–180.

- ^ Bowden 2010, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Hanson 1989, p. 341.

- ^ Griffiths 1975, pp. 315–317.

- ^ Turcan 1996, p. 121.

- ^ a b Salzman 1990, pp. 169–175.

- ^ Donalson 2003, pp. 68–73.

- ^ Alvar 2008, p. 299.

- ^ Alvar 2008, pp. 300–302.

- ^ Salzman 1990, pp. 232–236.

- ^ Turcan 1996, p. 128.

- ^ Salzman 1990, p. 239.

- ^ Salzman 1990, pp. 240–246.

- ^ Alvar 2008, p. 30.

- ^ Salzman 1990, p. 240.

- ^ Alvar 2008, pp. 383–385.

- ^ Beard, North & Price 1998, p. 286.

- ^ a b Bowden 2010, pp. 207–210.

- ^ Alvar 2008, pp. 390–394.

- ^ Alvar 2008, pp. 419–421.

- ^ Benko 1993, pp. 1–4.

- ^ Witt 1997, pp. 272–274, 277.

- ^ Benko 1993, pp. 263–265.

- ^ McGuckin 2008, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Heyob 1975, pp. 74–76.

- ^ Higgins 2012, pp. 72–74.

- ^ Mathews & Muller 2005, pp. 6–9.

- ^ Bolman 2005, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Higgins 2012, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Hornung 2001, pp. 189–191, 195–196.

- ^ Hornung 2001, pp. 78, 83–86.

- ^ van den Broek 2006, p. 478.

- ^ Haage 2006, p. 24.

- ^ Quentin 2012, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Hornung 2001, p. 196.

- ^ Macpherson 2004, p. 242.

- ^ Spieth 2007, pp. 50–52.

- ^ a b Hadot 2006, pp. 233–237.

- ^ Hadot 2006, pp. 266–269.

- ^ Assmann 1997, pp. 128–135.

- ^ Spieth 2007, pp. 91, 140.

- ^ Humbert 2000, pp. 175–178.

- ^ Quentin 2012, pp. 177–180.

- ^ Ziolkowski 2008, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Quentin 2012, pp. 225–227.

- ^ Humbert 2000, pp. 185, 188.

- ^ Donalson 2003, p. 170.

- ^ Witt 1997, p. 280.

- ^ Khazan 2014.

- ^ Hutton 2019, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Hutton 2019, pp. 82–84, 191–192.

- ^ Adler 1986, pp. 35–36, 56.

- ^ Forrest 2001, p. 236.