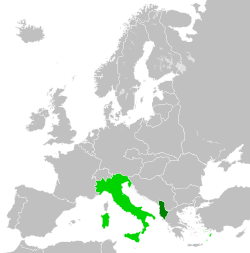

Italian invasion of Albania

| Italian invasion of Albania | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the interwar period | |||||||

Column of Italian forces in Albania. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Benito Mussolini Alfredo Guzzoni Giovanni Messe Ettore Sportiello |

Zog I Xhemal Aranitasi Abaz Kupi Mujo Ulqinaku † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

22,000 soldiers 400 aircraft[1] 2 battleships 3 heavy cruisers 3 light cruisers 9 destroyers 14 torpedo boats 1 minelayer 10 auxiliary ships 9 transport ships |

8,000 soldiers[2] 5 aircraft 3 torpedo boats | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Possibly 700 dead (according to Fischer)[3] 12–25 dead (Italian claim)[3][4] 97 wounded[4] |

Likely more than 700 dead (according to Fischer)[5] 160 dead and several hundreds wounded (according to Pearson)[4] 5 aircraft 3 torpedo boats | ||||||

| Events leading to World War II |

|---|

The Italian invasion of Albania was a brief military campaign which was launched by Fascist Italy against the Albanian Kingdom in 1939. The conflict was a result of the imperialistic policies of the Italian prime minister and dictator Benito Mussolini. Albania was rapidly overrun, its ruler King Zog I went into exile in neighboring Greece, and the country was made a part of the Italian Empire as a protectorate in personal union with the Italian Crown.

Background

Albania had long been of considerable strategic importance to the Kingdom of Italy. Italian naval strategists coveted the port of Vlorë and the island of Sazan because of their location at the entrance to the Bay of Vlorë and out to the Adriatic Sea. The Italians also wanted to construct a suitable base on Vlorë and Sazan for military operations in the Balkans.[6] In the late Ottoman period, with a local weakening of Islam, the Albanian nationalist movement gained the strong support of the two Adriatic sea powers of Austria-Hungary and Italy, which were concerned about pan-Slavism in the wider Balkans and also Anglo-French hegemony, purportedly represented in the area through Greece.[7] Before World War I Italy and Austria-Hungary had been supportive of the creation of an independent Albanian state.[8] At the outbreak of the war, Italy seized the chance to occupy the southern half of Albania, to avoid it being captured by the Austro-Hungarians. That success did not last long, as Albanian resistance during the subsequent Vlora War and post-war domestic problems forced Italy to pull out in 1920.[9] The desire to compensate for this failure would be one of Mussolini's major motives in invading Albania.[10]

Culturally and historically, Albania was important to the nationalistic aims of Italian Fascists,[citation needed] as the territory of Albania had long been part of the Roman Empire, even prior to the annexation of northern Italy by the Romans. Later, during the High Middle Ages, some coastal areas (like Durazzo) had been influenced and owned by Italian powers for many years. Chief among them were the Kingdom of Naples and the Republic of Venice (cf. Albania Veneta). The Italian Fascist regime legitimized its claim to Albania by conducting studies and using them to proclaim the racial affinity of Albanians and Italians, especially as opposed to the Slavic Yugoslavs.[11] Italian Fascists claimed that Albanians were linked to Italians through an ethnic heritage due to links between the prehistoric Italiotes, Roman and Illyrian populations, and they also claimed that the major influence over Albania of the Roman and Venetian empires justified Italy's right to possess it.[citation needed]

When Mussolini seized power in Italy, he turned to Albania with renewed interest. Italy began to penetrate Albania's economy in 1925, when Albania agreed to allow Italy to exploit its mineral resources.[12] That action was followed by the signing of the First Treaty of Tirana in 1926 and the signing of the Second Treaty of Tirana in 1927, which enabled Italy and Albania to form a defensive alliance.[12] Among other things, the Albanian government and economy were subsidised by Italian loans and the Royal Albanian Army was not only trained by Italian military instructors, most of the officers in the army were also Italians; other Italians were highly placed in the Albanian government. A third of Albanian imports came from Italy.[13]

Despite strong Italian influence, King Zog I refused to completely give in to Italian pressure.[14] In 1931, he openly stood up to the Italians, refusing to renew the 1926 Treaty of Tirana. After Albania signed trade agreements with Yugoslavia and Greece in 1934, Mussolini made a failed attempt to intimidate the Albanians by sending a fleet of warships to Albania.[dubious – discuss][15]

As Nazi Germany annexed Austria and moved against Czechoslovakia, Italy noticed that it was becoming the lesser member of the Pact of Steel.[dubious – discuss][16] Meanwhile, the imminent birth of an Albanian royal child threatened to give Zog the opportunity to establish a lasting dynasty. After Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia (March 15, 1939) without notifying Mussolini in advance, the Italian dictator decided to proceed with his annexation of Albania.[citation needed] Italy's King Victor Emmanuel III criticized Mussolini's plan to annex Albania by stating that it was an extremely unnecessary risk for an almost negligible gain.[17] Rome, however, delivered Tirana an ultimatum on March 25, 1939, demanding that it consent to Italy's occupation of Albania.[18] Zog refused to accept money in exchange for allowing a full Italian takeover and colonization of Albania.[citation needed]

The Albanian government tried to keep news of the Italian ultimatum secret.[citation needed] While Radio Tirana persistently broadcast claims in which it stated that nothing was happening, people became suspicious; and the news of the Italian ultimatum was spread by unofficial sources. On April 5, the king's son was born and the news of his birth was announced by the firing of cannons. Alarmed, people poured out into the streets, but the news of the birth of the new prince calmed them. People suspected that something else was going on, which led to an anti-Italian demonstration in Tirana the same day. On 6 April, several demonstrations were staged in Albania's main cities. That same afternoon, 100 Italian aircraft flew over Tirana, Durrës, and Vlorë, dropping leaflets which instructed the people to submit to Italian occupation. The people were infuriated by this demonstration of force and they called for the government to resist the Italian occupation and release all of the Albanians who were previously arrested on the suspicion that they were "communists". The crowd shouted, "Give us arms! We are being sold out! We are being betrayed!".[citation needed] While a mobilization of the reserves was called, many high-ranking officers left the country.[citation needed] The government began to dissolve. The Minister of the Interior, Musa Juka, left the country and moved to Yugoslavia the same day. While King Zog announced that he would resist the Italian occupation of his country, his people felt that they were being abandoned by their government.[19]

Invasion

The original Italian plans for the invasion called for the deployment of up to 50,000 men who would be supported by 51 naval units and 400 airplanes. Ultimately, the invasion force grew to 100,000 men who were supported by 600 airplanes,[20] but only 22,000 men actually took part in the invasion.[2] On April 7, Mussolini's troops, led by General Alfredo Guzzoni, invaded Albania, simultaneously attacking all Albanian ports. The Italian naval forces which were involved in the invasion consisted of the battleships Giulio Cesare and Conte di Cavour, three heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, nine destroyers, fourteen torpedo boats, one minelayer, ten auxiliary ships and nine transport ships.[21] The ships were divided into four groups that carried out landings at Vlorë, Durrës, Shëngjin and Sarandë. The Romanian Royal Army never deployed to Sarandë and Italy conquered the Romanian concession along with the rest of Albania during the invasion.[21]

On the other side, the regular Albanian army had 15,000 poorly equipped troops who had previously been trained by Italian officers. King Zog's plan was to mount a resistance in the mountains, leaving the ports and the main cities undefended; but Italian agents who were placed in Albania as military instructors sabotaged this plan. As a consequence, the resistance was mainly offered by the Royal Albanian Gendarmerie and small groups of patriots.

In Durrës, a force of 500 Albanians, including gendarmes and armed volunteers, led by Major Abaz Kupi (the commander of the gendarmerie in Durrës), and Mujo Ulqinaku, a naval sergeant, tried to halt the Italian advance. Equipped with small arms and three machine guns and supported by a coastal battery, the defenders resisted the Italians for a few hours before they were defeated by Italian naval fire.[20] The Royal Albanian Navy stationed in Durrës consisted of four patrol boats (each armed with a machine gun) and a coastal battery with four 75 mm guns, the latter also being involved in the fighting.[22] Mujo Ulqinaku, the commander of the patrol boat Tiranë, used his machine gun to kill and wound many Italian troops until himself being killed by an artillery shell from an Italian warship.[22][23] Eventually, a large number of light tanks were unloaded from the Italian ships. After that, resistance began to crumble, and within five hours the Italians had captured the city.[24]

By 1:30 pm on the first day, all Albanian ports were in Italian hands. King Zog, his wife, Queen Geraldine Apponyi, and their infant son Leka fled to Greece the same day, taking with them part of the gold reserves of the Albanian central bank. On hearing the news, an angry mob attacked the prisons, liberated the prisoners and sacked the King's residence. At 9:30 am on April 8, Italian troops entered Tirana and quickly captured all government buildings. Italian columns of soldiers then marched to Shkodër, Fier and Elbasan. Shkodër surrendered in the evening after 12 hours of fighting. During the Italian advance in Shkodër the mob besieged the prison and liberated some 200 prisoners.[25]

The number of casualties in these battles is disputed. Italian military reports stated that at Durrës 25 Italians were killed and 97 wounded, while the local townspeople claimed that 400 Italians were killed.[4] Casualties for the Albanians were given as 160 dead and several hundreds wounded.[4]

On April 12, the Albanian parliament voted to depose Zog and unite the nation with Italy "in personal union" by offering the Albanian crown to Italy's King Victor Emmanuel III.[26] The parliament elected Albania's largest landowner, Shefqet Vërlaci, as Prime Minister. Vërlaci served as interim head of state for five days until Victor Emmanuel III formally accepted the Albanian crown in a ceremony at the Quirinale palace in Rome. Victor Emmanuel III appointed Francesco Jacomoni di San Savino, a former ambassador to Albania, to represent him in Albania as "Lieutenant-General of the King" (effectively a viceroy).

In general, the Italian invasion was poorly planned and badly executed, and succeeded only because Albanian resistance was weak. As Filippo Anfuso, Count Ciano's chief assistant sarcastically commented "...if only the Albanians had possessed a well-armed fire-brigade, they could have driven us into the Adriatic".[27][28][29]

Aftermath

On April 15, 1939, Albania withdrew from the League of Nations, from which Italy had resigned in 1937. On June 3, 1939, the Albanian foreign ministry merged into the Italian foreign ministry, and Albanian Foreign Minister Xhemil Dino became an Italian ambassador. Upon the capture of Albania, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini declared the official creation of the Italian Empire and King Victor Emmanuel III was crowned King of the Albanians in addition to his title of Emperor of Ethiopia, which had been occupied by Italy three years before. The Albanian military was placed under Italian command and formally merged into the Italian Army in 1940. Additionally, the Italian Blackshirts formed four legions of Albanian Militia, initially recruited from Italian colonists living in Albania, but later from ethnic Albanians.[citation needed]

Upon the occupation of Albania and the installation of a new government, the economies of Albania and Italy were merged by a customs union which resulted in the removal of most trade restrictions.[30] Through a tariff union, the Italian tariff system was put in place in Albania.[30] Due to the expected economic losses in Albania from the alteration in tariff policy, the Italian government provided Albania 15 million Albanian leks each year in compensation.[30] Italian customs laws were to apply in Albania and only Italy alone could conclude treaties with third parties.[30] Italian capital was allowed to dominate the Albanian economy.[30] As a result, Italian companies were allowed to hold monopolies in the exploitation of Albanian natural resources.[30] All petroleum resources in Albania went through Agip, Italy's state petroleum company.[31]

Albania followed Italy into war against Britain and France on June 10, 1940. Albania served as the base for the Italian invasion of Greece in October 1940, and Albanian troops participated in the Greek campaign, but they massively deserted the front line. The country's southern areas (including the cities of Gjirokastër and Korçë) were temporarily occupied by the Greek army during that campaign. In May 1941, Albania was enlarged by the annexation of Kosovo and parts of Montenegro and the Vardar Banovina, going a long way towards the realization of nationalistic claims for a "Greater Albania". Part of the western coast of Epirus which was called Chameria was not annexed, instead, it was put under the rule of an Albanian High Commissioner who exercised nominal control of it. When Italy left the Axis powers in September 1943, German troops immediately occupied Albania after a short campaign, with relatively strong resistance.[32]

During the Second World War, the Albanian Partisans, including some Albanian nationalist groups, sporadically fought against the Italians (after autumn 1942) and, subsequently, they sporadically fought against the Germans. By October 1944, the Germans had withdrawn from the southern Balkans in response to military defeats which they had suffered at the hands of the Red Army, the collapse of Romania and the imminent fall of Bulgaria.[33] After the Germans left Albania due to the rapid advance of Albanian Communist forces, the Albanian Partisans crushed nationalist resistance and the leader of the Albanian Communist Party, Enver Hoxha, became the ruler of the country.[34]

Cultural references

The events which surrounded the Italian annexation of Albania formed part of the inspiration for the eighth volume of The Adventures of Tintin comics titled King Ottokar's Sceptre, with a plot based on a fictional Balkan country Syldavia and uneasy tensions with its larger neighbour Borduria.[35] The author of the Tintin comics Hergé also insisted that his editor publish the work to take advantage of current events in 1939 as he felt "Syldavia is Albania".[35]

See also

- Adriatic campaign of World War II

- Albanian Fascist Militia

- Albania–Italy relations

- Royal Albanian Army

- Royal Italian Army

References

- ^ Fischer 1999 (Purdue ed.), p. 21.

- ^ a b Fischer 1999 (Purdue ed.), p. 22.

- ^ a b Fischer 1999, p. 22:Reports on the number of casualties differed rather significantly. The townspeople of Durrës maintained that the Italians lost four hundred. Although Italian propaganda claimed that Italy only lost twelve men in the entire invasion, it is possible that approximately two hundred Italians were killed in Durrës alone and as many as seven hundred Italians may have been killed in total.

- ^ a b c d e Pearson 2004, p. 445.

- ^ Fischer, Bernd J. (1999a). Albania at war, 1939-1945. West Lafayette, Ind.: Purdue University Press. p. 22. ISBN 9781557531414.

Albanian casualties may have been higher.

- ^ Fischer 1999 (C. Hurst ed.), p. 5.

- ^ Kokolakis, Mihalis (2003). Το ύστερο Γιαννιώτικο Πασαλίκι: χώρος, διοίκηση και πληθυσμός στην τουρκοκρατούμενη Ηπειρο (1820–1913) [The late Pashalik of Ioannina: Space, administration and population in Ottoman ruled Epirus (1820–1913)]. Athens: EIE-ΚΝΕ. p. 91. ISBN 960-7916-11-5. "Περιορίζοντας τις αρχικές του ισλαμιστικές εξάρσεις, το αλβανικό εθνικιστικό κίνημα εξασφάλισε την πολιτική προστασία των δύο ισχυρών δυνάμεων της Αδριατικής, της Ιταλίας και της Αυστρίας, που δήλωναν έτοιμες να κάνουν ό,τι μπορούσαν για να σώσουν τα Βαλκάνια από την απειλή του Πανσλαβισμού και από την αγγλογαλλική κηδεμονία που υποτίθεται ότι θα αντιπροσώπευε η επέκταση της Ελλάδας." "[By limiting the Islamic character, the Albanian nationalist movement secured civil protection from two powerful forces in the Adriatic, Italy and Austria, which was ready to do what they could to save the Balkans from the threat of Pan-Slavism and the Anglo French tutelage that is supposed to represent its extension through Greece.]"

- ^ Hall, Richard C. (17 October 2014). Consumed by War: European Conflict in the 20th Century. University Press of Kentucky. p. 12. ISBN 9780813159959.

As a result of the Ottoman collapse, a group of Albanians, with Austrian and Italian support, declared Albanian independence at Valona (Vlorë) on 28 November 1912.

- ^ Albania: A Country Study: Albania's Reemergence after World War I, Library of Congress.

- ^ Stephen J. Lee (2003). Europe, 1890–1945. Psychology Press. p. 336–. ISBN 978-0-415-25455-7.

The invasion of Albania in 1939 resulted in the addition of territory on the Adriatic, a compensation for the territory Italy had not been given in the 1919 peace settlement. These policies were, however, carried out at immense cost, which eventually shattered the regime's limited infrastructure. There are also examples of direct

- ^ Kallis, Aristotle A. (2000), Fascist ideology: territory and expansionism in Italy and Germany, 1922–1945, Routledge, pp. 132–133, ISBN 9780415216128

- ^ a b Albania: A Country Study: Italian Penetration, Library of Congress

- ^ p. 149 Mack Smith, Denis Mussolini's Roman Empire Viking Press 1976

- ^ Fischer 1999 (C. Hurst ed.), p. 7.

- ^ Albania: A Country Study: Zog's Kingdom, Library of Congress

- ^ Albania: A Country Study: Italian Occupation, Library of Congress

- ^ p. 151 Mack Smith, Denis Mussolini's Roman Empire Viking Press 1976

- ^ Pearson, Owen (2004). Albania in the Twentieth Century, A History. Vol. I - Albania and King Zog. The Centre for Albanian Studies / I.B.Tauris. p. 429. ISBN 978-184511013-0.

- ^ Pearson 2004, p. 439.

- ^ a b Pearson 2004, p. 444.

- ^ a b La Regia Marina tra le due guerre mondiali.

- ^ a b "Zeqo">Zeqo, Mojkom (1980). Mujo Ulqinaku. Tirana, Albania: 8 Nëntori Pub. House.

- ^ Kore, Blerim (7 April 2009). "Kur mbreti italian Viktor Emanueli, vizitonte Gjirokastren". Koha Jone (in Albanian). Archived from the original on 8 October 2010. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ^ Pearson 2004, pp. 444–5.

- ^ Pearson 2004, p. 454.

- ^ Fischer 1999 (C. Hurst ed.), p. 36.

- ^ Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie; Fischer, Bernd Jürgen (2002). Albanian Identities: Myth and History. Indiana University Press. p. 139. ISBN 0253341892.

- ^ Fischer, Bernd Jürgen (1999). Albania at War, 1939–1945. Hurst. p. 23. ISBN 9781850655312.

- ^ Brewer, David (2016-02-28). Greece, the Decade of War: Occupation, Resistance and Civil War. I.B.Tauris. p. 2. ISBN 9780857729361.

- ^ a b c d e f Raphaël Lemkin. Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. Slark, New Jersey, US: The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., 2005. Pp. 102.

- ^ Pearson, Owen (2005). Albania in the Twentieth Century, A History. Vol. II - Albania in Occupation and War, 1939–45. The Centre for Albanian Studies / I.B.Tauris. p. 433. ISBN 978-184511104-5.

- ^ Fischer 1999 (C. Hurst ed.), p. 189.

- ^ Fischer 1999 (C. Hurst ed.), p. 223.

- ^ Albania: A Country Study: The Communist and Nationalist Resistance – Library of Congress.

- ^ a b Assouline, Pierre (2009) [1996]. Hergé, the Man Who Created Tintin. Charles Ruas (translator). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-19-539759-8.

Sources

- Fischer, Bernd J. (1999). Albania at War, 1939–1945. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-155753141-4 – via Google Books.

- Fischer, Bernd J. (1999). Albania at War, 1939–1945. C. Hurst & Co Publishers. ISBN 978-185065531-2.

- Library of Congress Country Study of Albania