Intrathecal administration

| Subarachnoid space | |

|---|---|

Diagrammatic representation of a section across the top of the skull, showing the membranes of the brain, etc. ("Subarachnoid cavity" visible at left.) | |

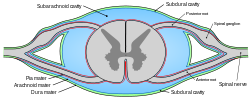

Diagrammatic transverse section of the medulla spinalis and its membranes. (Subarachnoid cavity colored blue.) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Spatium subarachnoideum, cavum subarachnoideale |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Intrathecal administration is a route of administration for drugs via an injection into the spinal canal, or into the subarachnoid space so that it reaches the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). It is useful in several applications, such as for spinal anesthesia, chemotherapy, or pain management. This route is also used to introduce drugs that fight certain infections, particularly post-neurosurgical. Typically, the drug is given this way to avoid being stopped by the blood–brain barrier, as it may not be able to pass into the brain when given orally. Drugs given by the intrathecal route often have to be compounded specially by a pharmacist or technician because they cannot contain any preservative or other potentially harmful inactive ingredients that are sometimes found in standard injectable drug preparations.

Intrathecal pseudodelivery is a technique where the drug is encapsulated in a porous capsule that is placed in communication with the cerebrospinal CSF. In this method, the drug is not released into the CSF. Instead, the CSF is in communication with the capsule through its porous walls, allowing the drug to interact with its target within the capsule itself. This allows for localized treatment while avoiding systemic distribution of the drug, potentially reducing side effects and enhancing the therapeutic efficacy for conditions affecting the central nervous system.

The route of administration is sometimes simply referred to as "intrathecal"; however, the term is also an adjective that refers to something occurring in or introduced into the anatomic space or potential space inside a sheath, most commonly the arachnoid membrane of the brain or spinal cord[1] (under which is the subarachnoid space). For example, intrathecal immunoglobulin production is production of antibodies in the spinal cord.[2] The abbreviation "IT" is best not used; instead, "intrathecal" is spelled out to avoid medical mistakes.[citation needed]

Applications of intrathecal administration

Anaesthetics/analgesics

Intrathecal administration of drugs for anaesthesia or analgesia can be utilized in the form of single-dose or continuous via catheter with external or internal pump depending on indication and duration needed. Usually a combination of a local anesthetic and one or more adjuvant drugs are used.

Intrathecal clonidine or dexmedetomidine can be used to prolong duration of anaesthesia and analgesia but comes with increased risk of hypotension.[3][4]

Lipophilic opioids such as fentanyl and sufentanil can be administered intrathecally for short duration of anaesthesia and analgesia.

Hydrophilic opioids such as morphine, diamorphine and hydromorphone can be administered intrathecally for longer duration of analgesia, up to 24 hours.

Pethidine has the unusual property of being both a local anaesthetic and opioid analgesic, which occasionally permits its use as the sole intrathecal anaesthetic agent.

Caution should be exercised with intrathecal opioids due to the risk of hypoventilation. Hydrophilic opioids comes with a dose-dependent risk of late onset hypoventilation, however, low-dose intrathecal hydrophilic opioids have similar risk for hypoventilation as systemic opioids.[5] Other adverse effects of intrathecal opioids include nausea and vomiting, pruritus and urinary retention.[6][citation needed]

Atypical analgesic agents

Antifungals

Amphotericin B is administered intrathecally to treat fungal infections involving the central nervous system infections.[7]

Cancer chemotherapy

Currently, only four agents are licensed for intrathecal cancer chemotherapy: methotrexate, cytarabine, hydrocortisone, and thiotepa.[8]

Administration of any vinca alkaloids, especially vincristine, via the intrathecal route is nearly always fatal.[9][10][11]

Baclofen

Often reserved for spastic cerebral palsy, baclofen can be administered through an intrathecal pump implanted just below the skin of the abdomen or behind the chest wall, with a catheter connected directly to the base of the spine. Intrathecal baclofen pumps sometimes carry serious clinical risks, such as infection or a possibly fatal sudden malfunction.[citation needed]

Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy

Treatment of chronic spinal injuries via the administration of mesenchymal stem cells,[12] either from adipose tissue or bone marrow, is experimental, with better results from the former method. Introduction of mesenchymal stem cells promote the microenvironment needed for axonal regrowth and reduction of inflammation caused by astrocytes proliferation and glial scar tissue.[13]

Animal models have shown improved motor control under the site of injury. A clinical trial also showed statistically significant improved sensitivity under the site of injury in patients.[14]

See also

- Cancer pain/Interventional/Intrathecal pump

- History of neuraxial anesthesia

- Intrathecal pump

- Theca

- Thecal sac

References

- ^ "Route of Administration". Data Standards Manual. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ Meinl, E; Krumbholz, M; Derfuss, T; Junker, A; Hohlfeld, R (2008). "Compartmentalization of inflammation in the CNS: a major mechanism driving progressive multiple sclerosis". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 274 (1–2): 42–4. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2008.06.032. PMID 18715571. S2CID 34995402.

- ^ Elia, N; Culebras, X; Mazza, C; Schiffer, E; Tramer, M (March 2008). "Clonidine as an Adjuvant to Intrathecal Local Anesthetics for Surgery: Systematic Review of Randomized Trials". Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. 33 (2): 159–167. doi:10.1016/j.rapm.2007.10.008.

- ^ Engelman, E.; Marsala, C. (January 2013). "Efficacy of adding clonidine to intrathecal morphine in acute postoperative pain: meta-analysis". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 110 (1): 21–27. doi:10.1093/bja/aes344.

- ^ Koning, Mark V.; Klimek, Markus; Rijs, Koen; Stolker, Robert J.; Heesen, Michael A. (September 2020). "Intrathecal hydrophilic opioids for abdominal surgery: a meta-analysis, meta-regression, and trial sequential analysis". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 125 (3): 358–372. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2020.05.061. PMC 7497029. PMID 32660719.

- ^ Chaney, Mark A. (October 1995). "Side effects of intrathecal and epidural opioids". Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia. 42 (10): 891–903. doi:10.1007/BF03011037. ISSN 0832-610X.

- ^ Nau, R; Blei, C; Eiffert, H (17 June 2020). "Intrathecal Antibacterial and Antifungal Therapies". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 33 (3). doi:10.1128/CMR.00190-19. PMC 7194852. PMID 32349999.

- ^ Grossman SA, Finklestein DM, Ruckdeschel JC, et al. (March 1993). "Randomized prospective comparison of intraventricular methotrexate and thiotepa with previously untreated neoplastic meningitis. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 11 (3): 561–9. doi:10.1200/jco.1993.11.3.561. PMID 8445432.

- ^ Schulmeister L (September 2004). "Preventing vincristine sulfate medication errors". Oncology Nursing Forum. 31 (5): E90–8. doi:10.1188/04.ONF.E90-E98. PMID 15378106.

- ^ Qweider M, Gilsbach JM, Rohde V (March 2007). "Inadvertent intrathecal vincristine administration: a neurosurgical emergency. Case report". Journal of Neurosurgery. Spine. 6 (3): 280–3. doi:10.3171/spi.2007.6.3.280. PMID 17355029.

- ^ International Medication Safety Network (2019), IMSN Global Targeted Medication Safety Best Practices, retrieved 2020-03-11.

- ^ Li, Man; Chen, Hong; Zhu, Mingxin (2022-12-13). "Mesenchymal stem cells for regenerative medicine in central nervous system". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 16. doi:10.3389/fnins.2022.1068114. ISSN 1662-453X. PMC 9793714. PMID 36583105.

- ^ Carrillo-Galvez, Ana Belén; Cobo, Marién; Cuevas-Ocaña, Sara; Gutiérrez-Guerrero, Alejandra; Sánchez-Gilabert, Almudena; Bongarzone, Pierpaolo; García-Pérez, Angélica; Muñoz, Pilar; Benabdellah, Karim; Toscano, Miguel G.; Martín, Francisco; Anderson, Per (2015-01-01). "Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Express GARP/LRRC32 on Their Surface: Effects on Their Biology and Immunomodulatory Capacity". Stem Cells. 33 (1): 183–195. doi:10.1002/stem.1821. ISSN 1066-5099. PMC 4309416. PMID 25182959.

- ^ Vaquero, Jesús; Zurita, Mercedes; Rico, Miguel A.; Aguayo, Concepcion; Bonilla, Celia; Marin, Esperanza; Tapiador, Noemi; Sevilla, Marta; Vazquez, David; Carballido, Joaquin; Fernandez, Cecilia; Rodriguez-Boto, Gregorio; Ovejero, Mercedes; Vaquero, Jesús; Zurita, Mercedes (2018-06-01). "Intrathecal administration of autologous mesenchymal stromal cells for spinal cord injury: Safety and efficacy of the 100/3 guideline". Cytotherapy. 20 (6): 806–819. doi:10.1016/j.jcyt.2018.03.032. ISSN 1465-3249. PMID 29853256.