Insects in Japanese culture

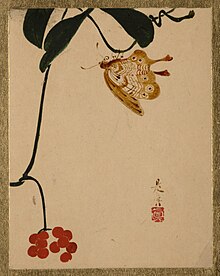

Within Japanese culture, insects have occupied an important role as aesthetic, allegorical, and symbolic objects.[1]: 185 In addition, insects have had a historical importance within the context of the culture and art of Japan.[1]: 185

Kenta Takada, longhorn beetle collector and author, noted that the Japanese appreciation for insects lies within the Shinto religion.[2] Shinto, a form of animism, places emphasis that every facet of the natural world is worthy of reverence as they are the creation of the spiritual dimension.[3] Takada additionally noted the importance of mono no aware, Zen awareness of the transience of all things, as an important factor within the perception of insects in a Japanese context.[3] Lafcadio Hearn remarked that "[the] belief in a mysterious relation between ghosts and insects, or rather between spirits and insects, is a very ancient belief in the East".[4]: 27

Historical context

Insects have occupied a place within Japanese culture for centuries. The Lady who Loved Insects, is a classic tale of a woman who collected caterpillars during the 12th century.[3] The Tamamushi Shrine, a miniature temple from the 7th century was formerly adorned with beetlewing from the jewel beetle Chrysochroa fulgidissima.[3]

Lafcadio Hearn, a European-American scholar who became a Japanese citizen in the 19th century remarked: "In old Japanese literature, poems upon insects are to be found by thousands".[3] Hearn's body of work while he was a citizen of Japan and as he analyzed Japanese literary works particularly focused on the comparative state of Western perceptions of insects compared to the Japanese ways of "[finding] delight, century after century, in watching the ways of insects".[4]: 11 Twelve of the eleven books that Hearn had written included passages devoted to insects.[4]: 14 In particular, Hearn wrote about Japanese tales regarding silkworms, cicadas, dragonflies,[4]: 14 flies, kusa-hibari (a cricket known under the scientific name Svistella bifasciata[5]), ants, fireflies, butterflies, and mosquitoes.[4]: 15

Entomophagy

Entomophagy has been a tradition within the regions of Gifu and Nagano, mountainous regions where there was a lack of fish and livestock for protein.[6] In times of famine, such as the end of the Second World War, the consumption of insects like inago and hachinoko served to supplement the diets of those with little access towards other forms of protein and vitamins. Consumption of insects waned when the Japanese people gradually gained access to higher-quality livestock products.[6] However the practice of entomophagy has been seeing a resurgence in recent years, with easily available packaged versions and with chefs looking for a sustainable food source popping up. Access to edible insects for the purpose of consumption have been gradually made easier with the advent of online shopping, as well as vending machines and retailers providing a supply. Additionally, cultural festivals, matsuri, provide a venue for consumption and highlighting local traditions of entomophagy.[6] The Kushihara Hebo Matsuri of Ena, Gifu, is an example of such an event. Where beekeepers cultivate and then proceed to try and harvest the most hachinoko.[6][7]

Inago - Orthoptera

The consumption of grasshoppers, known as inago in the Japanese language, is considered a luxury food product.[3]

Hachinoko - Hymenoptera

In the Chūbu region of central Japan, local people raise wasp or bee larvae for the purposes of consumption.[3] The larvae are referred to as hachinoko.[6] Foraged wasps are consumed at all life stages, from larva to adult.[3] The type of wasp harvested is known in places where insects are consumed, such as Gifu Prefecture, as hebo.[7] Hebo is consumed only during the month of November, and is a local delicacy in mountainous regions.[7] The name refers to two species[7] of black wasp (identified as クロスズメバチ, kuro-suzumebachi, Vespula flaviceps[8][9]), an easy to catch and non-aggressive species of wasp. During the Kushihara Hebo Matsuri, foraged wasp nests are weighed in a competition to determine which is the largest for a trophy. The festival itself arising from the need to protect local customs by older wasp foragers during 1993.[7] The consumption of hebo is understood to be more of a supplementary food source, rather than as a primary means of nutrition, with individuals coming across and harvesting the larvae when coming across them by chance.[7] The Kushihara region of Gifu was unique in that locals would actively seek out wasp nests and would subsequently raise them at their own home.[7]

Hebo and hachinoko more broadly is consumed in a variety of ways. Hebo gohan is cooked rice mixed with the wasp larvae. Hebo gohei mochi, grilled mochi served with a sauce consisting of wasp larvae, miso, and peanuts.[7]

In addition to hebo, the more aggressive Vespa mandarina japonica is additionally consumed by the people of Kushihara.[7]

Insect-related hobbies

Hobbies involving insects have always been a popular within Japanese culture, ranging from competitive beetle wrestling, to the more casual raising of beetles for the purpose of keeping them as pets, and childhood pastimes of catching insects in nearby forests and parks.[10]

The practice of collecting beetles and crickets for the purpose of keeping them as pets is a common hobby for children in Japan.[3] Some are captured for the purpose of fighting one another.[11] However, the concept of beetle wrestling is a relatively new concept.[10]

The live trade of exotic beetles is a common practice for collectors young and old. Live specimens have been known to exceed 10 million yen,[12] or $94,000, in retail price.[10] Locally sourced beetles can sell for 100 yen, while the exotic varieties can go up to 1.2 million yen in price.[13] The kabutomushi, Japanese rhinoceros beetle, can sell at convenience stores for between 500 and 1000 yen.[14] The largest market for the insect trade have been men in their 30s and 40s.[10] The trade of insects, particularly beetles, have been incorporated in everyday locations, in addition to specialty stores,[10] such as department stores and vending machines.[15][14][3] Additionally, there exist televised matches of beetle wrestling competitions and petting zoos featuring beetles.[3]

Beetle wrestling

Beetle wrestling, or more broadly referred to as bugfighting,[14] is a form of competition whereby two beetles are provoked in order to try to flip over or toss its opponent,[14] or haul its opponent out of the ring[16] through the use of their mandibles.[10] Another way to lose the match is if the beetle walks out of the ring.[13] Not all competitions involve provoking violence between beetles, in the context of the National Rhinoceros Beetle Sumo Tournament, beetles are made to climb meter-tall tree branches.[17] Beetles are deliberately trained for combat, Shin Yuasa, a previous victor, trained his beetle by prompting his beetle to fight smaller beetles, thus "[getting] him into the habit of winning."[16]

Beetle wrestling tends to inflict very little harm to the beetle itself,[13] as the beetles involved have little to harm their opponents, with few instances of insect death during events.[14] Critics of the sport question the ethics of pitting insects against each other, some viewers of the sport raise questions regarding the morality of the sport, akin to cockfighting or dog fighting.[12] Fights involving other varieties of insects or other arthropods with stingers, such as scorpions and centipedes, can also result in severe injury to the participant arthropod.[12] Those who host wrestling matches online insist that the participants are kept "happy and comfortable"[12] in their care.

Tournaments of beetle wrestling have found online spaces, such as YouTube to livestream tournaments.[16][12] Cash prizes are often awarded to winners. Betting is common among those who watch tournaments, particularly in Okinawa Prefecture, despite the practice being banned in Japan.[14] Tessho Suzuki, eight years old, won a national tournament and was awarded beef and plums from Nakayama, Yamagata.[16][17]

An adverse effect of the intense fascination with the practice of beetle wrestling is that it can fuel demand for wildlife smuggling to take place. One of the leading causes for beetle population decline has been directly due to poaching for fighting exhibitions.[16] Beetles such as Dynastes satanas, which are rare and protected under CITES, are not protected under Japanese law through the Invasive Alien Species Act.[16] In addition, Japanese policy has eased restrictions for the import of rare beetles, due to the perception that exotic beetles are not a threat to the local ecosystem.[10] Japanese markets demand exotic species, as local ones tend to be short-lived, whereas exotic species such as members of the genus Dynastes can live up to two years.[16] As a result of intense demand, populations of rare beetles and other insects are poached by smugglers seeking Japanese markets, where demand for rare insects is high for the purposes of beetle wrestling, the pet trade, and preservation.[16] In 2007, Hosogushi Masatsugu was arrested in Mariscal Sucre International Airport for his attempt in smuggling 423 rare species of beetles.[16] Despite several arrests, beetle poaching remains prolific in nations such as Bolivia as a result of a lack of oversight on the Peruvian border.[16]

Insect collecting

Insects as pets

Beetles require relatively little attention when kept as pets. Some exotic species can live up to five years, and rearing beetles has been described as "good for relieving stress."[10]

Symbolic uses

The firefly occupies a place within the Japanese perception of summer. Poets, including Matsuo Basho, Yosa Buson, and Issa Kobayashi[11] employ the firefly as a kigo, phrase associated with a particular season, within the body of their works. Fireflies appear as the second most prevalent kigo within their works.[11] In addition, classical literature has had a focus on the transient lives of the mayfly as well as the chirping calls of the cricket.[10]

In music

(アブラゼミ)

(スズムシ)

Japanese people view the sounds that insects produce as "soothing" or "comfortable".[11] While Westerners perceive the sounds of insects as "noise" and processed through the right brain, Japanese people perceive insect sounds as a "voice" in the left brain.[11] The capture and sale of "insect musicians", insects that produce audible calls, was a popular practice in the animal trade sector during eighteenth and nineteenth century Japan, alongside the trade of live birds.[4]: 14

Two sounds that feature heavily within the perception of insect sounds in Japan are the sounds of cicadas and bell crickets. Cicada emergence in Japan occurs during the summer, and is often associated with the season. The sound of cicada calls in unison is referred to as the "cicada drizzle",[11] as the sound of harmonizing cicadas resembles the sounds of falling rain. The bell cricket's (Meloimorpha japonica) clear-sounding chirping cry during the autumn season has been described as giving a "refreshing feeling" to those listening.[11] Capturing the bell cricket for the use of hearing their cries during the evening has been a cultural practice since ancient times.[11]

Conservation

In 2003, Japan had 500 organizations dedication to the preservation of satoyama, mixed use human settlement and natural area in regions where mountains and flatlands intersect. There exists a high amount of biodiversity due to the lack of a monoculture, as most species cannot solely dominate the curated landscape. It is thought by Japanese entomologists Minoru Ishii and Yasuhiro Nakamura, that the preservation of satoyama would be crucial for the recovery of declining insect populations.[3]

In popular culture

Monster collecting franchise Pokémon was inspired by its creator, Satoshi Tajiri's childhood hobby of collecting and capturing insects.[11] Tajiri expressed his interest in sharing his experiences in capturing and collecting creatures with the younger generation.[14] Within the games themselves bug-inspired Pokémon exist.[3] Such as Mega-Heracross, inspired by the Hercules beetle.[16]

The practice of beetle fighting is a core part of the 2001 Sega video game Mushiking. 20,000 competitions were officially set up from the hype surrounding the franchise. The game's popularity was further boosted by popular media's and related merchandise highlighting of the sport.[12]

The kabutomushi, Japanese rhinoceros beetle, is a ubiquitous design motif for pop culture mascots. In addition to Heracross, whose base form is inspired by the rhinoceros beetle,[14] other characters based on, or inspired by, the rhinoceros beetle include Medabee (Medabots), Gravity Beetle (Mega Man X3), and Kabuterimon (Digimon).[14]

Mothra, a gigantic moth monster appears prominently within the kaiju genre with films, is second to Godzilla in number of film appearances. Its prominence within kaiju media has been attributed to Japan's unique relationship with insects.[3]

References

- ^ a b Tsoumas, Johannis (1 July 2019). "Insects in Japanese culture". Figura. 7 (1). Universidade Estadual de Campinas. doi:10.20396/figura.v7i1.9944 (inactive 1 November 2024). ISSN 2317-4625. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Takada, Kenta (2012). "Is interest in dynastine beetles really uniquely Japanese and of little interest to people in Western countries?" (PDF). Elytra. 2 (2).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Appleton, Andrea; Hains, Brigid. "Japanese culture conquered the human fear of creepy-crawlies". Aeon. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Lurie, David B. (2016). "Orientomology: The Insect Literature of Lafcadio Hearn". The Green Book: Writings on Irish Gothic, Supernatural and Fantastic Literature (8): 7–42. ISSN 2009-6089. JSTOR 48536123. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ Kawabe, Toru. "クサヒバリ". 昆虫エクスプローラ. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "An Acquired Taste of Japan – Inago and Hachinoko!". Zojirushi America Corporation. 16 March 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Amoroso, Phoebe (18 February 2020). "The Japanese village that eats wasps". BBC Travel. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ "へぼ料理 - Hebo Ryori". 岐阜県農政部農産物流通課 (in Japanese). Gifu Prefectural Government. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ "へぼ飯 愛知県". うちの郷土料理:農林水産省. Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Iijima, Masako (30 June 2000). "Japanese are going buggy". Deseret News. Reuters. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Geeraert, Amélie (9 September 2020). "Petting Beetles: The Strange Love of Japanese People for Insects". Kokoro Media. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Hartenberger, Carla (31 March 2008). "Bug Fights, Hot Trend". The Tyee. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Osaka, Chika; Fahmy, Miral; Joyce, Rodney (1 August 2008). "Battle of the beetles heats up summer in Tokyo". Reuters. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Inglese, Frank (12 April 2016). "A Look Into The Strange World Of Japanese Beetle Fighting". SnapThirty. Archived from the original on 22 September 2022. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Berton, Eduardo Franco (4 February 2020). "Why rare beetles are being smuggled to Japan at an alarming rate". National Geographic. Archived from the original on February 22, 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Kids cheer on their bugs at the Kabutomushi Sumo Competition". The Japan Times. 23 July 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2021.