Ingapirca

Hatun Cañar / Inka Pirka | |

Ingapirca, the temple of the sun | |

| Region | Cañar Province |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 2°32′54.9168″S 78°52′18.768″W / 2.548588000°S 78.87188000°W |

| History | |

| Cultures | Inca |

| Site notes | |

| Public access | yes |

| Website | http://www.complejoingapirca.gob.ec/ |

Ingapirca (Kichwa: Inka Pirka, "Inca wall") is a town in Cañar Province, Ecuador, and the name of the older Inca ruins and archeological site nearby.[1][2]

These are the largest known Inca ruins in Ecuador.[3] The most significant building is the Temple of the Sun, an elliptically shaped building constructed around a large rock.

History

This area had long been settled by the Cañari indigenous people, who called it Hatun Cañar. As the Inca Empire expanded into southern Ecuador, the Inca Túpac Yupanqui encountered the Cañari "Hatun Cañar" tribe. He had difficulties in conquering them. He used different political strategies, marrying the Cañari princess and improving the Cañari city of Guapondelig, calling it Tumebamba or Pumapungo (present-day Cuenca).[citation needed]

The Inca and Cañari decided to settle their differences and live together peacefully. The astronomical observatory was built under Inca Huayna Capac. The Inca renamed the city as Ingapirca and kept most of their distinctive customs separately, as the Cañari did theirs. Although the Inca were more numerous, they did not demand that the Cañari give up their autonomy.[citation needed]

The castle complex is of Cañari-Inca origin. Its purpose is uncertain. The complex was used as a fortress and storehouse from which to resupply Inca troops en route to northern Ecuador. At Ingapirca they also developed a complex underground aqueduct system to provide water to the entire compound.[citation needed]

The Temple of the Sun is the most significant building whose partial ruins survive at the archeological site. It is constructed in the Inca way without mortar, as are most of the structures in the complex. The stones were carefully chiseled and fashioned to fit together perfectly. It was positioned in keeping with their beliefs and knowledge of the cosmos. Researchers have learned by observation that the Temple of the Sun was positioned so that on the solstices, at exactly the right time of day, sunlight would fall through the center of the doorway of the small chamber at the top of the temple. Most of this chamber has fallen down.[citation needed]

The people had numerous ritual celebrations at the complex. They prepared gallons of a local fermented drink to consume in the rituals of these festivals. As sun and moon worshipers, they tried to be as close to their gods as possible, and built their monuments high in the mountains.

The weather changes rapidly, within minutes, ranging from calm and sunny one minute and rainy, windy, and cold another minute. This climate volatility is typical year round. The people felt strongly that this was the place where the gods had led them, regardless of the climate.[citation needed]

Charles Marie de La Condamine became the first European to make a scientific description of Ingapirca, which he visited in 1739 in the course of his expedition to South America.[4]

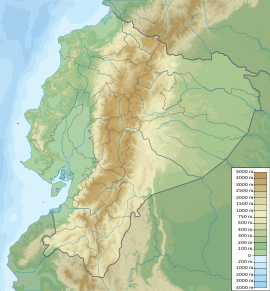

Map

See also

References

- ^ Hyslop, John (19 February 2014). Inka Settlement Planning. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. p. 384. ISBN 9780292762640. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ Greenspan, Eliot (1 June 2011). Frommer's Ecuador and the Galapagos Islands (3rd ed.). USA: Frommer's. p. 214. ISBN 9781118100325. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ Lauderbaugh, George (22 February 2012). The History of Ecuador. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 5. ISBN 9780313362514. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ Barnes, Monica; Fleming, David (1989). "Charles-Marie de La Condamine's Report on Ingapirca and the Development of Scientific Field Work in the Andes, 1735-1744". Andrean Past. 2 (1): 175–236.

External links

- (in Spanish) Official website of the archaeological complex