Indo people

Indische Nederlanders Orang Indo | |

|---|---|

Indo brother and sister, Dutch East Indies, 1931 | |

| Total population | |

| 581,000 (2001)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 458,000 (2001)[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Dutch (Indonesian Dutch) and Indonesian historically Malay,[2] Petjo, and Javindo | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Christianity (Protestantism—especially Dutch Reformed or Lutheran; Roman Catholicism); minority—Judaism and Islam[3][4] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Dutch people, other Eurasians and Indonesian peoples, Cape Malays, Afrikaners[5] | |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Indo people |

|---|

The Indo people (Dutch: Indische Nederlanders, Indonesian: Orang Indo) or Indos are Eurasian people living in or connected with Indonesia. In its narrowest sense, the term refers to people in the former Dutch East Indies who held European legal status but were of mixed Dutch and indigenous Indonesian descent as well as their descendants today.

In the broadest sense, an Indo is anyone of mixed European and Indonesian descent. Indos are associated with colonial culture of the former Dutch East Indies, a Dutch colony in Southeast Asia and a predecessor to modern Indonesia after its proclamation of independence shortly after World War II.[6][7][8][9] The term was used to describe people acknowledged to be of mixed Dutch and Indonesian descent, or it was a term used in the Dutch East Indies to apply to Europeans who had partial Asian ancestry.[9][10][11][12][13] The European ancestry of these people was predominantly Dutch, but also included Portuguese, German, British, French, Belgian and others.[14]

The term "Indo" is first recorded from 1898,[15] as an abbreviation of the Dutch term Indo-European. Other terms used at various times are 'Dutch Indonesians', 'Eurasians',[16] 'Indo-Europeans', 'Indo-Dutch'[9] and 'Dutch-Indos'.[17][18][19][20][21]

Overview

In the Indonesian language, common synonymous terms are Sinjo (for males), Belanda-Indo, Indo-Belanda,[22] Bule,[23] and Indo means Eurasian: a person with European and Indonesian parentage.[24] Indo is an abbreviation of the term Indo-European which originated in the Dutch East Indies of the 19th century as an informal term to describe the Eurasians. Indische is an abbreviation of the Dutch term Indische Nederlander. Indische was a term that could be applied to everything connected with the Dutch East Indies.[13] In the Netherlands, the term Indische Nederlander includes all Dutch nationals who lived in the Dutch East Indies, either Dutch or mixed ancestry. To distinguish between the two, Eurasians are called Indo and native Dutch are called Totok.[19] In the Dutch East Indies (today's Indonesia), these families formed "a racially, culturally and socially homogeneous community between the Totoks (European newcomers) and the indigenous population".[12][13] They were historically Christians and spoke Dutch, Portuguese, English and Indonesian.[2][25][26][27][28] They were compared to Afrikaners from South Africa, who also share Dutch ancestry and culture, but are not mixed-race.[5][29]

In the 16th-18th centuries, Eurasians were referred to by a Portuguese term mestiço (Dutch: Mesties) or as coloured (Dutch: Kleurling). Additionally, a wide range of more contumelious terms, such as liplap, can be found in the literature.[30]

History of European trade and colonialism in Southeast Asia (16th century – 1949)

Portuguese and Spanish in Southeast Asia (16th century)

Eurasians in the Dutch East Indies were descendants of Europeans who travelled to Asia between the 16th and the 20th century.[31] The earliest Europeans in South East Asia were Portuguese and Spanish traders. Portuguese explorers discovered two trade routes to Asia, sailing around the south of Africa or the Americas to create a commercial monopoly. In the early 16th century, the Portuguese established important trade posts in South East Asia, which was a diverse collection of many rival kingdoms, sultanates and tribes spread over a huge territory of peninsulas and islands. A main Portuguese stronghold was in the Maluku Islands (the Moluccas), the fabled "Spice Islands". The Spanish established a dominant presence further north in the Philippines. These historical developments were instrumental in building a foundation for large Eurasian communities in this region.[32] Old Eurasian families in the Philippines mainly descend from the Spanish. While the oldest Indo families descend from Portuguese traders and explorers,[33] some family names of old Indo families include Simao, De Fretes, Pereira, Henriques, etc.[34][35][36][37][38][39]

Dutch and English in Southeast Asia (17th and 18th century)

During the 1620s, Jan Pieterszoon Coen in particular insisted that families and orphans be sent from Holland to populate the colonies. As a result, a number of single women were sent and an orphanage was established in Batavia to raise Dutch orphan girls to become East India brides.[5] Around 1650, the number of mixed marriages, frequent in the early years of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), declined sharply. There was a large number of women from the Netherlands recorded as marrying in the years around 1650. At least half the brides of European men in Batavia came from Europe. Many of these women were widows, already previously married in the Indies, but almost half of them were single women from the Netherlands marrying for the first time. There were still considerable numbers of women sailing eastwards to the Indies at this time. The ships' passenger lists from the 17th century also evidence this. Not until later in the 17th century did the numbers of passengers to Asia drop drastically.[13]

Given the small population of their country, the Dutch had to fill out their recruitment for Asia by looking for overseas emigration candidates in the underprivileged regions of north-western Europe.[40] Originally, most Dutch VOC employees were traders, accountants, sailors and adventurers. In 1622, over half the Batavia garrison of 143 consisted of foreigners (Germans were the majority among them), there were also French, Scots, English, Danes, Flemings, and Walloons (they were half of the VOC overall).[2][41][42][43] Europeans living in Batavia also included Norwegians, Italians, Maltese, Poles, Irish, Spaniards, Portuguese, and Swedes.[44] The number of Swedes travelling to the East on Dutch ships numbered in the thousands. Many settled in Batavia for long periods.[45] Some of the settlers in the 18th and early 19th centuries were men without wives, and intermarriage occurred with the local inhabitants; others brought their families. The VOC and later the colonial government to a certain extent encouraged this, partly to maintain their control over the region.[46] The existing Indo (or Mestizo) population of Portuguese descent was therefore welcome to integrate.[47][48] An Indo-European society developed in the East Indies.[49] Although most of its members became Dutch citizens, their culture was strongly Eurasian in nature, with a focus on both Asian and European heritage. 'European' society in the Indies was dominated by this Indo culture into which non-native born European settlers integrated. The non-native-born (totok) Europeans adopted Indo culture and customs. The Indo lifestyle (e.g. language and dress code) only came under pressure to westernise in the following centuries of formal Dutch colonization.[2] This would change after the formal colonisation by the Dutch in the 19th century.[50][51][52][53]

Eurasian men were recruited by the colonial regime as go-betweens in both the civil administration and the military, where their mastery of two languages was useful. Few European women came to the Indies during the Dutch East India Company period to accompany the administrators and soldiers who came from the Netherlands.[54][55] There is evidence of considerable care by officers of the Dutch East India Company for their illegitimate Eurasian children: boys were sometimes sent to the Netherlands to be educated, and sometimes never returned to Indonesia.[56] Using the evidence of centuries old Portuguese family names many Indos carried matriarchal kinship relations within Eurasian communities, it has been argued by Tjalie Robinson that the origin of the Indo was less of a thin facade laid over a Dutch foundation, but sprang from an ancient mestizo culture going back all the way to the beginning of the European involvement in Asia.[57]

In 1720, Batavia's population consisted of 2,000 Europeans, mainly Dutch merchants (2.2 percent of the total population), 1,100 Eurasians, 11,700 Chinese, 9,000 non-Indonesian Asians of Portuguese culture (mardijkers), 600 Indo-Arab Muslims, 5,600 immigrants from a dozen islands, 3,500 Malays, 27,600 Javanese and Balinese, and 29,000 slaves of varying ethnic origins including Africans.[58]

By the beginning of the eighteenth century, there were new arrivals of Europeans in Malacca who made it their new home and became part of the Malacca Dutch community.[59]

Dutch East Indies (1800–1949)

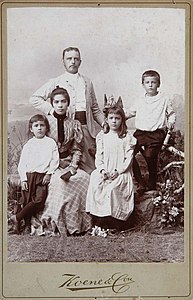

- Studio portrait of an Indo-European family, Dutch East Indies (ca. 1900)

- Europeans and Eurasians in Sumatra, early 20th century

In 1854, over half of the 18,000 Europeans in Java were Eurasians.[55] In the 1890s, there were 62,000 civilian 'Europeans' in the Dutch East Indies, most of them Eurasians, making up less than half of one per cent of the population.[60] Indo influence on the nature of colonial society waned following World War I and the opening of the Suez Canal, when there was a substantial influx of white Dutch families.[13]

By 1925, 27.5 percent of all Europeans in Indonesia who married chose either native or mixed-blood spouses, a proportion that remained high until 1940, when it was still 20 percent.[61] By 1930, there were more than 240,000 people with European legal status in the colony, still making up less than half of one percent of the population.[62] Almost 75% of these Europeans were in fact native Eurasians known as Indo-Europeans.[63] The majority of legally acknowledged Dutchmen were bi-lingual Indo Eurasians.[64] Eurasian antecedents were no bar to the highest levels of colonial society.[65] In 1940, it was estimated that they were 80 percent of the European population, which at the previous census had numbered 250,000.[12]

An Indo movement led by the Indo Europeesch Verbond (Indo European Alliance) voiced the idea of independence from the Netherlands, however only an Indo minority led by Ernest Douwes Dekker and P.F.Dahler joined the indigenous Indonesian independence movement.[66] Examples of famous Indo people in the Dutch East Indies include Gerardus Johannes Berenschot.

Political organisations

- Indische Party est. 1912

- Insulinde (Political Party) est. 1913

- Indo Europeesch Verbond est. 1919

- Freemasonry in the Dutch East Indies

Japanese occupation (1942–1945)

During World War II, the European colonies in South East Asia, including the Dutch East Indies, were invaded and annexed by the Japanese Empire.[67] The Japanese sought to eradicate anything reminiscent of European government. Many of the Indies Dutch had spent World War II in Japanese concentration camps.[68] All full blooded Europeans were put in Japanese concentration camps while the larger (Indo) European population, who could prove close native ancestry, were subjected to a curfew, usually in their homes, which was known as Buiten Kampers (Dutch for outside campers).[69] First the POWs, then all male adults and finally all females with their children and adolescents were interned. Boys of 10 years old and older were separated from their mothers and put into a boys camp usually together with old men. While the women were interned with children in women's camps, Vrouwenkampen[70] all working age men were interned as forced unpaid labor.[citation needed] The Japanese failed in their attempts to win over the Indo community, and Indos were made subject to the same forceful measures.[71]

"Nine-tenths of the so-called Europeans are the offspring of whites married to native women. These mixed people are called Indo-Europeans… They have formed the backbone of officialdom. In general they feel the same loyalty to the Netherlands as do the white Dutch. They have full rights as Dutch citizens and they are Christians and follow Dutch customs. This group has suffered more than any other during the Japanese occupation".

— Official US Army publication for the benefit of G.I.'s, 1944.[72]

Indonesian Independence struggle (1945–1949)

Leaders of the Indonesian independence movement cooperated with the Japanese to realise an independent nation. Two days after Japan's surrender in August 1945, the independence leaders declared an independent Republic of Indonesia. The majority of Indo males were either captive or in hiding and remained oblivious to these developments.[73] During the occupation, the Japanese had imprisoned some 42,000 Dutch military personnel and around 100,000 civilians, mostly Dutch people who could not provide proof of Indonesian descent.[74] During the Japanese occupation, the Dutch were put into the lowest class. Native blood was the only thing that could free Indos from being put into concentration camps,[75] 160,000 Indos (Eurasians) were not herded into camps.[74] It is estimated that 8,200 european POW and 16,800 Indo people and European civilians died in Japanese concentration camps and the number of Indo people who died outside the camps is unknown.[76]

On 24 November 1945, Sutomo leaked propaganda to specifically kill the Dutch, Indo, Ambonese and unarmed civilians,[75] Hundreds of Eurasians were killed in attacks by fanatical nationalistic Indonesian youth groups in the Bersiap Period during the last quarter of 1945,[77][78] and it is estimated that around 5,500 to 20,000 Indo people and European civilians people were killed and 2,500 went missing during bersiap period.[79][80][81][82]

So of the 290,000 Indo people and European before the Japanese occupation of which around 260,000 are Dutch citizens, it is estimated that more than 50,000 died during the japan occupation until bersiap period.[76][79]

Emigration from the Dutch East Indies (1945–1965)

Over 10% of the "Indo-Europeans" took Indonesian citizenship after Indonesian independence.[83] Most retained full Dutch citizenship after the transfer of sovereignty to Indonesia in 1949.[84]

In 1949, 300,000 Eurasians who had been socialized into many Dutch customs were repatriated.[41] The Dutch established a repatriation programme which lasted until 1967.[75] Over a 15-year period after the Republic of Indonesia became an independent state, virtually the entire Dutch population, Indische Nederlanders (Dutch Indonesians), estimated at between 250,000 and 300,000, left the former Dutch East Indies.[85][86]

Most of them moved to the Netherlands. Many had never been there before.[9][85] Some of them went to Australia, the United States or Canada. 18.5% departed for the United States.[87][88] In 1959, Dutch people who did not embrace Indonesian citizenship were expelled.[2] An estimated 60,000 immigrated to the United States in the 1960s.[21]

The migration pattern of the so-called Repatriation progressed in five distinct waves over a period of 20 years.

- The first wave, 1945–1950: After Japan's capitulation and Indonesia's declaration of independence, around 100,000 people, many former captives that spent the war years in Japanese concentration camps and then faced the turmoil of the violent Bersiap period, left for the Netherlands. Although Indos suffered greatly during this period, with 5,500 people killed in the last Bersiap period, the great majority did not leave their place of birth until the next few waves.

- The second wave, 1950–1957: After formal Dutch recognition of Indonesia's independence,[89] many civil servants, law enforcement, and defence personnel left for the Netherlands. The colonial army was disbanded and at least 4,000 of the South Moluccan price soldiers and their families were also relocated to the Netherlands. The exact number of people that left Indonesia during the second wave is unknown. According to one estimate, 200,000 moved to the Netherlands in 1956.[90]

- The third wave, 1957–1958: During the political conflict around the 'New-Guinea Issue', Dutch citizens were declared undesired elements by the young Republic of Indonesia and around 20,000 more people left for the Netherlands.

- The fourth wave, 1962–1964: When the last Dutch-controlled territory (New Guinea), was released to the Republic of Indonesia, the last remaining Dutch citizens left for the Netherlands, including around 500 Papua civil servants and their families. The total number of people that migrated is estimated at 14,000.

- The fifth wave, 1949–1967: During this overlapping period a distinctive group of people, known as Spijtoptanten (Repentis), who originally opted for Indonesian citizenship found that they were unable to integrate into Indonesian society and also left for the Netherlands. In 1967, the Dutch government formally terminated this option.[63] Of the 31,000 people who originally opted for Indonesian citizenship (Indonesian term: Warga negara Indonesia), 25,000 withdrew their decision over the years.[91][92][93]

Many Indos who left for the Netherlands often continued the journey of their diaspora to warmer places, such as California and Florida in the United States.[94] A 2005 study estimates the number of Indos who went to Australia around 10,000.[95] Research has shown that most Indo immigrants are assimilating into their host societies.[96] The Indos are disappearing as a group.[97]

United States

Notable Americans whose families came from the Dutch East Indies include the musicians Eddie Van Halen, Alex Van Halen[98][99][100] and Michelle Branch, the actor Mark-Paul Gosselaar,[101][102][103] and the video game designer Henk Rogers.[104][105]

During the 1950s and 1960s an estimated 60,000 Indos arrived in the US, where they have integrated into mainstream American society. These Indos were sometimes also referred to as Indo-Europeans and Amerindos.[106] They are a relatively small Eurasian refugee-immigrant group in the US.[17]

Indos who emigrated to the US following Indonesian independence assimilated into their new country, marrying people outside the community; most never returned to Indonesia.[21] Migration to the US occurred under legislative refugee measures; these immigrants were sponsored by Christian organizations such as the Church World Service and the Catholic Relief Services. An accurate count of Indo immigrants is not available, as the US Census classified people according to their self-determined ethnic affiliation. The Indos may have been included in overlapping categories of "country of origin", "other Asians," "total foreign", "mixed parentage", "total foreign-born" and "foreign mother tongue". However the Indos who settled via the legislative refugee measures number at least 25,000.[96]

The original post-war refugee legislation of 1948, already adhering to a strict 'affidavit of support' policy, was still maintaining a color bar making it difficult for Indos to emigrate to the US. By 1951, US consulates in the Netherlands registered 33,500 requests and had waiting times of 3 to 5 years. Also the US Walter-McCarran Act (1953) adhered to the traditional American policy of limiting immigrants from Asia. The yearly quota for Indonesia was limited to 100 visas, even though Dutch foreign affairs attempted to profile Indos as refugees from the alleged pro-communist Sukarno administration.[96]

The 1953 flood disaster in the Netherlands resulted in the US Refugee Relief Act including a slot for 15,000 ethnic Dutch who had at least 50% European blood (one year later loosened to Dutch citizens with at least two Dutch grandparents) and a clean legal and political record. In 1954, only 187 visas were actually granted. Partly influenced by the anti-western rhetoric and policies of the Sukarno administration, anti-communist US Representative Francis E. Walter pleaded for a second term of the Refugee Relief Act in 1957 and an additional slot of 15,000 visas in 1958.[96]

In 1958, the US Pastore-Walter Act ("Act for the relief of certain distressed aliens") was passed allowing for a one-off acceptance of 10,000 Dutchmen from Indonesia (excluding the regular annual quota of 3,136 visas). It was hoped however that only 10% of these Dutch refugees would in fact be racially mixed Indos and the American embassy in The Hague was frustrated with the fact that Canada, which was more strict in ethnic profiling, was getting the full–blooded Dutch and the US was getting Dutch "all rather heavily dark". Still in 1960 senators Pastore and Walter managed to get a second 2-year term for their act which was used by a great number of Indo 'Spijtoptanten' (Repentis).[96]

The Indos who immigrated and their descendants can be found in all fifty US states, with a majority in southern California.[107] The 1970 US Census recorded 28,000 foreign-born Dutch (Dutch not born in the Netherlands) in California, while the six traditional states with strong Dutch population numbers (Michigan, New York, New Jersey, Illinois, Washington and Florida) hosted most of the other 50,000 foreign-born Dutch.[94] The formation of Indo enclaves did not occur because of various factors. Indos settled initially with their sponsors or in locations offered them by the sponsor. Indos also had a wide variety of occupations and in this respect were not limited to certain geographic areas. There were no forces in the host society limiting the choice of location; there was a full choice as to where to settle.[106]

Unlike in the Netherlands, US Indos did not increase numerically because of their relative small numbers and their geographical dispersion. Also the disappearance of a proverbial "old country" able to supply a continual influx of new immigrants stimulates the rapid assimilation of Indos into the US. Although several Indo clubs[108] have existed throughout the second half of the 20th century, though the community's elders are passing away steadily. Some experts expect that within the lifespan of the second and third-generation descendants, the community will be assimilated and disappear completely into American multicultural society.[109] The great leap in technological innovation of the 20th and 21st centuries, in the areas of communication and media, is mitigating the geographical dispersion and diversity of American Indos. Triggered by the loss of family and community elders, US Indos are starting to rapidly reclaim their cultural heritage as well as a sense of community.[106][110]

Australia

Notwithstanding Australia's ‘White Australia policy’ during the 1950s and 1960s, approximately 10,000 Indos migrated to Australia, mostly via the Netherlands. With regard to mixed-race Eurasians, who were called NPEO (Non Pure European Origine) by the Australian Ministries, subjective decision-making became the norm of the policy until the 1970s.[96]

During WWII, a large refugee community from the Dutch East Indies existed in Australia of which 1,000 chose to stay in Australia after the War.[96] The Dutch-Australian agreement (1951), to stimulate immigration to Australia did not bypass Australia's overall 'White Australia Policy', which considerably hampered the immigration of Indos.[96]

In the early 1950s, Australian immigration officials based in the Netherlands screened potential Indo migrants on skin color and western orientation. Refusals were never explained. Notes to the applicants contained this standard sentence in English: "It is not the policy of the department to give reasons so please do not ask".[96] In 1956, an Australian security official publicly stated in the Australian newspaper that Dutch Eurasians may become a serious social problem and even an Asian fifth column.[96]

In the early 1960s, only vocationally skilled migrants were accepted to Australia. Originally, applicants were required to be of 100% European descent. Later, Indos were required to show a family tree proving 75% European descent. Eventually, the key question posed by Australian officials was: "Would they be noticed, if they walked down the streets of Canberra or Melbourne or Sydney, as being European or non-European?"[96]

In the 1970s, in an attempt to make the policy more objective, a procedure was implemented that gave the applicant the opportunity to ask for a second opinion from a different official. Both decisions were then weighed by a higher official. Moreover, Anti-Asian migration policies started to change and in 1976 Australian immigration officials were even dispatched to Asia. Consequently, Indo-migrants were less and less subject to discrimination based on skin color.[96]

The Netherlands

- See also List of Dutch Indos

- Demonstration of Indische Euraziatischen in The Hague (1954).

Indos in the Netherlands are considered an ethnic minority, and most of them are of mixed European-Indonesian origin bearing European family names.[111]

In 1990, the Dutch Central Bureau for Statistics (CBS) registered the number of first-generation Indos living in the Netherlands at around 180,000 people. In 2001, official registration, including the second generation, accumulate their numbers to around half a million. Based on this the estimations, which include the third-generation descendants, reach up to at least 800,000 people. However, researcher Dr. Peter Post of the NIOD estimates 1.5 to 2 million people with Indo blood live in the Netherlands. The Indo-Dutch living abroad were not included. That makes them by far the largest minority community in the Netherlands.[112]

Integration

The Indo community is considered the best-integrated ethnic and cultural minority in the Netherlands. Statistical data compiled by CBS shows that Indos belong to the group with the country's lowest crime rates.[113]

A 1999 CBS study reveals that of all foreign-born groups living in the Netherlands, only the Indos have an average income similar to that of citizens born in the Netherlands. Job participation in government, education, and health care is similar as well. A 2005 CBS study, among foreign-born citizens and their children living in the Netherlands, shows that on average, Indos own the largest number of independent enterprises. A 2007 CBS study shows that over 50% of first-generation Indos have married a native-born Dutch person, which increased to 80% for the second generation.[114][115] One of the first and oldest Indo organisations that supported the integration of Indo repatriates into the Netherlands is Pelita.[116]

Although Indo repatriates,[117] being born overseas, are officially registered as Dutch citizens of foreign descent, their Eurasian background puts them in the Western sub-class instead of the Non-Western (Asian) sub-class.

Two factors are usually attributed to the essence of their apparently seamless assimilation into Dutch society: Dutch citizenship, and the amount of 'Dutch cultural capital', in the form of school attainments and familiarity with the Dutch language and culture, which Indos already possessed before migrating to the Netherlands.[118]

Culture

There were few public signs of the Indo culture. The most visible one was the yearly event Pasar Malam Besar (the Great Night Market) in The Hague that currently continues under the name Tong Tong Fair.[119]

Indo culinary culture has made an enduring impact on Dutch society. There is no other place outside Indonesia with such an abundance of Indonesian food available.[120] Indos played a pivotal role in introducing both Indonesian cuisine and Indo fusion cuisine to the Netherlands, making it so popular that some consider it an integral part of Dutch cuisine.[121] The Countess C. van Limburg Stirum writes in her book "The Art of Dutch Cooking" (1962): here exist countless Indonesian dishes, some of which take hours to prepare; but a few easy ones have become so popular that they can be regarded as "national dishes". She provides recipes for dishes that have become commonplace in the Netherlands: nasi goreng (fried rice), pisang goreng (fried bananas), lumpia goreng (fried spring rolls), bami (fried noodles), satay (grilled skewered meat), satay sauce(peanut sauce), and sambal ulek (chilli paste).[121] Most towns in the Netherlands will have an Indies or Indonesian restaurant and toko (shop). Even most Chinese restaurants have added Indonesian dishes to their menu such as babi panggang (roasted pork), and many now call themselves Chinese Indies Restaurants.[120]

Indo influence in Dutch society is also reflected in the arts, i.e. music[122][123] and literature.

An important champion of Indo culture was the writer Tjalie Robinson (1911–1974), who co-founded the Tong Tong Fair.[124][125] Louis Couperus' Of Old People, the Things that Pass (Van oude mensen, de dingen die voorbij gaan, 1906) is a well-known example of an older Indies narrative. Maria Dermoût is known as a nostalgic Indies writer. Marion Bloem's postmemory work evolves around an artistic exploration of Indo identity and culture, which puts her in the tradition of Tjalie Robinson.[84][126]

Immigrants and descendants in the Netherlands

Eurasians were officially part of the European legal class. They were formally considered to be Dutch and held Dutch passports.[55][127]

Notwithstanding the fact that Indos in the former colony of the Dutch East Indies were officially part of the European legal class and were formally considered to be Dutch nationals, the Dutch government always practiced an official policy of discouragement with regard to the post-WWII repatriation of Indos to the Netherlands.[128] While Dutch policy was in fact aimed at stimulating Indos to give up Dutch citizenship and opt for Indonesian citizenship, simultaneously the young Indonesian Republic implemented policies increasingly intolerant towards anything remotely reminiscent of Dutch influence. Even though actual aggression against Indos decreased after the extreme violence of the Bersiap period, all Dutch (language) institutions, schools and businesses were gradually eliminated and public discrimination and racism against Indos in the Indonesian job market continued. In the end, 98% of the original community moved to Europe.[129]

In the Netherlands, the first generation immigrants quickly adapted to the host society's culture and at least outwardly adopted its customs.[130] Exactly as was the case in the old colony the necessity to blend in with dominant Dutch culture remained paramount for social and professional advancement.[131]

Unlike in the Dutch East Indies, pressure to assimilate invaded even the intimacy of the private household. On a regular basis, Indos who were lodged in guest houses were carefully screened by social workers for so–called 'oriental practices', including the private use of any language other than Dutch, the home preparation of Indonesian food, wearing clothing from the Indies, using water for hygiene in the toilet and even the practice of taking daily baths.[129][132]

Netherlands

Dutch society does not impose a compulsory ethnic identity on "Dutch Eurasians" because no community exists. Although third- and fourth-generation Indos[133] are part of a fairly large minority community in the Netherlands, the path of assimilation ventured by their parents and grandparents has left them with little knowledge of their actual roots and history, even to the point that they find it hard to recognise their own cultural features. Some Indos find it hard to grasp the concept of their Eurasian identity and tend to either disregard their Indonesian roots or attempt to profile themselves as Indonesian.[134][135] In recent years, the reinvigorated search for roots and identity has also produced several academic studies.[136]

In her master thesis published in 2010, Dutch scholar Nora Iburg[137] argues that for third-generation descendants of Indos in the Netherlands there is no need to define the essence of a common Indo group identity and concludes that for them there is in fact no true essence of Indo identity except for its hybrid nature.[138]

Indonesia

- See also List of Indonesian Indos

“[…] the place that the Indos […] occupy in our colonial society has been altered. In spite of everything, the Indos are gradually becoming Indonesians, or one could say that the Indonesians are gradually coming to the level of the Indos. The evolution of the deeply ingrained process of transformation in our society first established the Indos in a privileged position, and now that same process is withdrawing those privileges. Even if they retain their 'European' status before the law, they will still be on a level with the Indonesians, because there are and will continue to be many more educated Indonesians than Indos. Their privileged position thus is losing its social foundation, and as a result that position itself will also disappear".

— Sutan Sjahrir, 1937[139]

During colonial times, Indos were not always formally recognized and registered as Europeans. A considerable number of Indos integrated into their respective local indigenous societies and have never been officially registered as either European or Eurasian sub-group. The exact numbers are unknown.[13]

In Malang, the Indo upper class is clustered in particular neighbourhoods and Sunday ceremony in the Sion Church is still in Dutch. In Bandung, over 2000 poor Indos are supported by overseas organisations such as Halin[140] and the Alan Neys Memorial Fund.[141] In Garut, there are ethnic Indos (Dutch Indonesians) there are Dutch Villages (Kampung Belanda) in the Dayeuh Manggung Tea Plantation Area. In Jakarta, some services in Immanuel Church are still in Dutch.[142] Cities like Semarang, Surabaya, Magelang and Sukabumi still have significant communities.

Another place with a relatively large Dutch-speaking Indo community is Depok, on Java.[143] Smaller communities still exist in places such as Kampung Tugu in Koja, Jakarta.[144] Recently after the Aceh region in Sumatra became more widely accessible, following post-tsunami relief work, the media also discovered a closed Indo Eurasian community of devout Muslims in the Lamno area, mostly of Portuguese origin.[145][146][147][148][149][150]

During the Suharto era, like the Chinese minority in Indonesia also most Indos have changed their family names and some have converted to Islam to blend into the Pribumi-dominated society and prevent discrimination. The latest trend among Indo-Chinese and Indo-Europeans is to change them back.[151]

See also

- Anglo-Burmese people

- Anglo-Indian people

- Afrikaners

- Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad

- Bersiap

- Bụi đời

- Decolonisation of Asia

- Dutch Indies literature

- Hafu

- Hotel des Indes (Batavia)

- Indies Monument

- Indo cuisine

- Kristang people

- Njai

- Pasar Malam Besar

- Spanish Filipino

- Stranger King (Concept)

- Volksraad (Dutch East Indies)

References

Notes and citations

- ^ a b van Imhoff, Evert; Beets, Gijs (2004). "A demographic history of the Indo-Dutch population, 1930–2001". Journal of Population Research. 21 (1): 47–72. doi:10.1007/BF03032210. JSTOR 41110781.

- ^ a b c d e Taylor, Jean Gelman. The Social World of Batavia: European and Eurasian in Dutch Asia (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1983). ISBN 978-0-300-09709-2

- ^ Steijlen, Fridus (2009). Indisch en Moluks religieus leven in na-oorlogs Nederland. The Hague: Stichting Tong Tong, Indische School.

- ^ http://www.tongtong.nl/indische-school/contentdownloads/steijlen.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b c Dutch Colonialism, Migration and Cultural Heritage. KITLV Press. 2008. pp. 104, 115.

- ^ van Amersfoort, H. (1982). "Immigration and the formation of minority groups: the Dutch experience 1945-1975". Cambridge University Press.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Sjaardema, H. (1946). "One View on the Position of the Eurasian in Indonesian Society". The Journal of Asian Studies. 5 (2): 172–175. doi:10.2307/2049742. JSTOR 2049742. S2CID 158287493.

- ^ Bosma, U. (2012). Post-colonial Immigrants and Identity Formations in the Netherlands. Amsterdam University Press. p. 198.

- ^ a b c d van Imhoff, E.; Beets, G. (2004). "A demographic history of the Indo-Dutch population, 1930–2001". Journal of Population Research. 21 (1): 47–49. doi:10.1007/bf03032210. S2CID 53645470.

- ^ Lai, Selena (2002). Understanding Indonesia in the 21st Century. Stanford University Institute for International Studies. p. 12.

- ^ J. Errington, Linguistics in a Colonial World: A Story of Language, 2008, Wiley-Blackwell, p. 138

- ^ a b c The Colonial Review. Department of Education in Tropical Areas, University of London, Institute of Education. 1941. p. 72.

- ^ a b c d e f Bosma, U.; Raben, R. (2008). Being "Dutch" in the Indies: a history of creolisation and empire, 1500–1920. University of Michigan, NUS Press. pp. 21, 37, 220. ISBN 978-9971-69-373-2. "Indos–people of Dutch descent who stayed in the new republic Indonesia after it gained independence, or who emigrated to Indonesia after 1949–are called 'Dutch-Indonesians'. Although the majority of the Indos are found in the lowest strata of European society, they do not represent a solid social or economic group."

- ^ van der Veur, P. (1968). "The Eurasians of Indonesia: A Problem and Challenge in Colonial History". Journal of Southeast Asian History. 9 (2): 191–207. doi:10.1017/s021778110000466x.

- ^ "Zoekresultaten". etymologiebank.nl.

- ^ Knight, G. (2012). "East of the Cape in 1832: The Old Indies World, Empire Families and "Colonial Women" in Nineteenth-century Java". Itinerario. 36: 22–48. doi:10.1017/s0165115312000356. S2CID 163411444.

- ^ a b Greenbaum-Kasson, E. (2011). "The long way home". The Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Betts, R. (2004). Decolonization. Psychology Press. p. 81.

- ^ a b Yanowa, D.; van der Haar, M. (2012). "People out of place: allochthony and autochthony in the Netherlands' identity discourse—metaphors and categories in action". Journal of International Relations and Development. 16 (2): 227–261. doi:10.1057/jird.2012.13. S2CID 145401956.

- ^ Pattynama, P. (2012). "Cultural memory and Indo-Dutch identity formations". The University of Amsterdam: 175–192.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c Asrianti, Tifa (10 January 2010). "Dutch Indonesians' search for home". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ "Eurasians were referred to by native Indonesians as Sinjo (or Njo for short)". A. Adam, The Vernacular Press and the Emergence of Modern Indonesian Consciousness (1855-1913), Cornell Press, 1995, p. 12

- ^ Detha Arya Tifada (15 June 2020). Yudhistira Mahabarata (ed.). "Asal-usul Sebutan 'Bule' untuk Warga Asing". Voice of Indonesia (in Indonesian). Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ Echols, J. (1989). An Indonesian-English Dictionary. Cornell University Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-979-403-756-0.

- ^ de Vries, J. (1988). "Dutch Loanwords in Indonesian". International Journal of the Sociology of Language (73): 121–136. doi:10.1515/ijsl.1988.73.121. S2CID 201727339.

- ^ Rath, J.; Nell, L. (2009). Ethnic Amsterdam: immigrants and urban change in the twentieth century. Amsterdam University Press. p. 131.

- ^ Wertheim, W. (1947). "The Indo-European Problem in Indonesia". Pacific Affairs. 20 (3): 290–298. doi:10.2307/2752163. JSTOR 2752163.

- ^ Ming, H. (1983). "Barracks-concubinage in the Indies, 1887-1920" (PDF). Indonesia. 35 (35): 65–94. doi:10.2307/3350866. hdl:1813/53765. JSTOR 3350866.

- ^ Milone, P. (1967). "Indische Culture, and Its Relationship to Urban Life". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 9 (4): 407–426. doi:10.1017/s0010417500004618. S2CID 143944726.

- ^ Quote: "Liplap: A vulgar and disparaging nickname given in the Dutch East Indies to Eurasians." See: Yule, Henry, Coke Burnell, Arthur Hobson-Jobson: the Anglo-Indian dictionary (Publisher: Wordsworth Editions, 1996) p. 518

- ^ van Goor, J.; van Goor, F. (2004). Prelude to Colonialism: The Dutch in Asia. Uitgeverij Verloren. p. 57.

- ^ Notable Mestizo communities with Portuguese roots are the Larantuka and Topasses people, a powerful and independent group of Mestizo, who controlled the sandalwood trade and who challenged both the Dutch and Portuguese. Their descendants live on the islands of Flores and Timor to this day. Boxer, C.R., The Topasses of Timor,(Indisch Instituut, Amsterdam, 1947).

- ^ Many Portuguese family names can be found on the islands of Ambon, Flores and East Timor. Although most Portuguese family names were adopted after conversion to the Christian religion, many families can still trace their roots to Portuguese ancestors. (in Dutch) Rumphius, G.E. De Ambonse landbeschrijving (Landelijk steunpunt educatie Molukkers, Utrecht, 2002) ISBN 90-76729-29-8

- ^ Van Der Kroef, Justus M. (1955). "The Indonesian Eurasian and His Culture". Phylon. 16 (4): 448–462. doi:10.2307/272662. JSTOR 272662.

- ^ (in Portuguese) Pinto da Franca, A. Influencia Portuguesa na Indonesia (In: 'STUDIA N° 33', pp. 161-234, 1971, Lisbon, Portugal)

- ^ (in Portuguese) Rebelo, Gabriel Informaçao das cousas de Maluco 1569 (1856 & 1955, Lisboa, Portugal)

- ^ Boxer, C. R. Portuguese and Spanish Projects for the Conquest of Southeast Asia, 1580-1600 (In: 'Journal of Asian History' Vol. 3, 1969; pp. 118-136)

- ^ "Braga Collection National Library of Australia". Nla.gov.au. Archived from the original on 18 August 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ "Timeline Milestones 1". Gimonca.com. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Etemad, Bouda (2007). Possessing the world: taking the measurements of colonisation from the 18th to the 20th century. Berghahn Books. p. 20.

- ^ a b Thomas Janoski, The Ironies of Citizenship: Naturalization and Integration in Industrialized Countries (Cambridge University Press, 2010) pp. 163,168 ISBN 0-521-14541-4

- ^ Megan Vaughan, Creating the Creole Island: Slavery in Eighteenth-Century Mauritius (2005) p. 7

- ^ Murdoch, Steve (2005). Network North: Scottish Kin, Commercial And Covert Associations in Northern. Brill. p. 210.

- ^ Donald F. Lach, Edwin J. Van Kley, Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume III: A Century of Advance. Book 3: Southeast Asia (1998) p. 1317

- ^ Huigen, Siegfried; De Jong, Jan; Kolfin, Elmer (2010). The Dutch Trading Companies As Knowledge Networks. Brill. p. 362.

- ^ Boxer, C.R. (1991). The Dutch Seaborne Empire 1600–1800. Penguin. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-14-013618-0.

- ^ The language of trade was Malay with Portuguese influences. To this day the Indonesian language has a relatively large vocabulary of words with Portuguese roots e.g. Sunday, party, soap, table, flag, and school.

- ^ "Throughout this period Indo people were also referred to by their Portuguese name: Mestizo". Kitlv-journals.nl. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ In this time period the word (and country) 'Indonesia' did not exist yet. Neither was the colony of the 'Dutch East Indies' founded yet.

- ^ Blusse, Leonard, Strange company: Chinese settlers, Mestizo women, and the Dutch in VOC Batavia (Dordrecht-Holland; Riverton, U.S.A., Foris Publications, 1986. xiii, 302p.) no.: 959.82 B659

- ^ Boxer, C. R., Jan Compagnie in war and peace, 1602-1799: a short history of the Dutch East-India Company (Hong Kong, Heinemann Asia, 1979. 115p.) number: 382.060492 B788

- ^ Masselman, George, The cradle of colonialism (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1963) no.: 382.09492 MAS

- ^ "Timeline Milestones 2". Gimonca.com. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ A Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures: Continental Europe. Edinburgh University Press. p. 342.

- ^ a b c van der Kroef, J. (1953). "The Eurasian Minority in Indonesia". American Sociological Review. 18 (5): 484–493. doi:10.2307/2087431. JSTOR 2087431.

- ^ Lehning, James (2013). European Colonialism since 1700. Cambridge University Press. pp. 145, 147.

- ^ Goss, Andrew From Tong-Tong to Tempo Doeloe: Eurasian Memory Work and the Bracketing of Dutch Colonial History, 1957-1961 (Publisher: University of New Orleans, New Orleans, 2000) P.26-27 Online History Faculty Publications UNO

- ^ Dirk, Hoerder (2002). Cultures in Contact: World Migrations in the Second Millennium. Duke University Press. p. 183.

- ^ Laura Jarnagin, Portuguese and Luso-Asian Legacies in Southeast Asia, 1511-2011, vol. 2: Culture and Identity in the Luso-Asian World: Tenacities & Plasticities (2012) p. 266

- ^ Therborn, Göran (2004). Between Sex and Power: Family in the World, 1900-2000. Psychology Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0415300773.

- ^ Frances Gouda, Dutch Culture Overseas: Colonial Practice in the Netherlands Indies, 1900-1942 (2008) p. 165

- ^ Beck, Sanderson, South Asia, 1800–1950 – World Peace Communications (2008) ISBN 978-0-9792532-3-2 By 1930 more European women had arrived in the colony, and they made up 113,000 out of the 240,000 Europeans.

- ^ a b Van Nimwegen, Nico De demografische geschiedenis van Indische Nederlanders, Report no. 64 (Publisher: NIDI, The Hague, 2002) p. 36 ISBN 9789070990923

- ^ Meijer, Hans (2004). In Indie geworteld. Bert bakker. pp. 33, 35, 36, 76, 77, 371, 389. ISBN 978-90-351-2617-6.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Knight, G. (2000). Narratives of Colonialism: Sugar, Java, and the Dutch. Nova Science Publishers. p. 48.

- ^ 'E.F.E. Douwes Dekker (known after 1946 as Danudirja Setyabuddhi), a Eurasian journalist, descendant of the author Max Havelaar, a veteran of the Boer War (1899–1902) fighting on the Afrikaner side. Douwes Dekker criticized the Ethical Policy as excessively conservative and advocated self-government for the islands and a kind of "Indies nationalism" that encompassed all the islands' permanent residents but not the racially exclusive expatriates (Dutch: Trekkers) (Indonesian: Totok).' Ref: Country studies. US Library of Congress.

- ^ L., Klemen (1999–2000). "Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941-1942". Archived from the original on 26 July 2011.

- ^ Smith, Andrea (2003). Europe's Invisible Migrants: Consequences of the Colonists' Return. Amsterdam University Press. p. 16.

- ^ "Buitenkampers: The outlawed Eurasians? The position of binnen-and buitenkampers compared from 1942 to 1949". 31 January 2015.

- ^ "Stichting Japanse Vrouwenkampen - Welkom".

- ^ Touwen-Bouwsma, Elly Japanese minority policy: the Eurasians on Java and the dilemma of ethnic loyalty No.4 vol. 152 (1996) pp. 553-572 (KITLV Press, Leiden, Netherlands, 1997) ISSN 0006-2294

- ^ War and Navy Departments of the United States Army, 'A pocket guide to the Netherlands East Indies.' (Facsimile by Army Information Branch of the Army Service Forces re-published by Elsevier/Reed Business November 2009) ISBN 978-90-6882-748-4 p. 18

- ^ "NIOD (Dutch War Documentation) website with camp overview". Indischekamparchieven.nl. 8 December 1941. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ a b Raben, Remco (1999). Representing the Japanese Occupation of Indonesia. Personal Testimonies and Public Images in Indonesia, Japan, and the Netherlands. Washington University Press. p. 56.

- ^ a b c Sidjaja, Calvin Michel (22 October 2011). "Who is responsible for 'Bersiap'?". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ a b "The Japanese Occupation and Pacific War (in numbers)". www.niod.nl.

- ^ Post, Peter; Touwen-Bouwsma, Elly (1997). Japan, Indonesia, and the War: Myths and Realities. KITLV Press. p. 48.

- ^ Frederick, William H. (2012). "The killing of Dutch and Eurasians in Indonesia's national revolution (1945–49): A 'brief genocide' reconsidered". Journal of Genocide Research. 14 (3–4): 359–380. doi:10.1080/14623528.2012.719370. S2CID 145622878.

- ^ a b "Indonesian War of Independence (in numbers)". NIOD. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Kemperman, Jeroen (16 May 2014). "De slachtoffers van de Bersiap" [The Victims of the Bersiap]. Niodbibliotheek.blogspot.com (in Dutch). Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ "The Dark Side Of The Revolution Of Independence: A Period Of Unscrupulous Preparedness". VOI - Waktunya Merevolusi Pemberitaan.

- ^ Borch, Fred L. (2017). "Setting the Stage: The Dutch in the East Indies from 1595 to 1942". Military Trials of War Criminals in the Netherlands East Indies 1946-1949. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198777168.003.0002. ISBN 978-0-19-877716-8.

- ^ R. B. Cribb, Audrey Kahin, Historical Dictionary of Indonesia (2004) p. 185

- ^ a b Bosma, Ulbe (2012). Post-Colonial Immigrants and Identity Formations in the Netherlands. Amsterdam University Press. p. 139.

- ^ a b Robinson, Vaughan; Andersson, Roger; Musterd, Sako (30 July 2003). Spreading the 'burden'?: A Review of Policies to Disperse Asylum Seekers and ... - Vaughan Robinson, Roger Andersson, Sako Musterd - Google Books. Policy Press. ISBN 9781861344175. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Herzog, B. (2013). Anticolonialism, decolonialism, neocolonialism. Blackwell Publishing. p. 21.

- ^ "Status of Indos in the United States". Amerindo.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ "Indo's and Moluccans in the Netherlands: How did they get there? | YOUR GATEWAY TO SOUTHEAST ASIA". Latitudes.nu. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ "uit Indonesi overdracht souvereiniteit en intocht van president Sukarno in Djakarta;embed=1 Link to video footage". Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Frijhoff, Willem; Spies, Marijke (2004). Dutch Culture in a European Perspective: 1950, prosperity and welfare - Google Books. Royal Van Gorcum. ISBN 9789023239666. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Note: These people are known by the Dutch term: 'Spijtoptanten' See:nl:Spijtoptant (English: Repentis)

- ^ "Timeline Milestones 8". Gimonca.com. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ "Passenger lists archive". Passagierslijsten1945-1964.nl. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ a b Brinks, Herbert (2010). "Dutch Americans, Countries and Their Cultures".

- ^ Cote, Joost; Westerbeek, Loes (2005). Recalling the Indies: Colonial Culture and Postcolonial Identities. Askant Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-90-5260-119-9. Archived from the original on 11 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Willems, Wim "De uittocht uit Indie (1945–1995), De geschiedenis van Indische Nederlanders" (Publisher: Bert Bakker, Amsterdam, 2001) p. 254 ISBN 90-351-2361-1

- ^ David Levinson, Melvin Ember, American immigrant cultures: builders of a nation (1997) p. 441

- ^ "Music News: Latest and Breaking Music News". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 25 July 2009. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ "100 Greatest Guitar Solos - tablature for the best guitar solos of all time". Guitar.about.com. 14 November 2013. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Allmusic.org

- ^ Gosselaar, Mark-Paul (15 October 2008). "Catching up with...Mark-Paul Gosselaar". The Washington Post. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Rohit, Parimal M. (3 March 2011). "Mark-Paul Gosselaar Discusses Franklin and Bash". Santa Monica Mirror. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Mark-Paul Gosselaar...From Outrageous Con Man To Reluctant Icon!". Mark-Paul Gosselaar.net. 2005. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "The Story of Tetris: Henk Rogers". Sramana Mitra. 16 September 2009. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ "Henk B. Rogers' Page". TechHui. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ a b c Krancher, Jan Indos: The Last Eurasian Community in the USA? Article adapted from "American Immigrant Cultures – Builders of a Nation," volume 1, 1997, Simon and Schuster McMillan. (Publisher: Eurasian Nation, April 2003) Online transcript: Berkeley University Website[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Holland Festival in L.A., CA". Latimesblogs.latimes.com. 26 May 2009. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ American Indo organisation publishing the magazine De Indo once established by Tjalie Robinson. In 2007 its publisher Creutzburg was awarded Dutch royal honours in Anaheim, California for 44 years of dedication to his community.

- ^ Indos in the USA (article on the Eurasian Nation platform)

- ^ Joe Fitzgibbon/Special to The Oregonian (5 November 2009). "Portland (US) News Article about new Indo Eurasian documentary (dd. Nov. 2009)". Oregonlive.com. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Spaan, Ernst; Hillmann, Felicitas; van Naerssen, Ton (2005). Asian Migrants and European Labour Markets: Patterns and Processes of Immigrant Labour Market Insertion in Europe. Taylor & Francis US. p. 240.

- ^ "Official CBS 2001 census document, p. 58" (PDF). Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Van Amersfoort, Hans; Van Niekerk, Mies (2006). "Indo immigration as a colonial inheritance: post-colonial immigrants in the Netherlands, 1945-2002". Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 32 (3): 323–346. doi:10.1080/13691830600555210. S2CID 216142383.

- ^ De Vries, Marlene (2009). Indisch is een gevoel, de tweede en derde generatie Indische Nederlanders. Amsterdam University Press. p. 369. ISBN 978-90-8964-125-0. Archived from the original on 17 August 2009.

- ^ Vries, Marlene de (1 January 2009). 'Indisch is een gevoel': de tweede en derde generatie Indische Nederlanders. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789089641250 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Pelita founded and operated by Indos celebrated its 60-year jubilee in 2007". Archived from the original on 31 October 2013.

- ^ CBS. "CBS".

- ^ Van Amersfoort, Hans (2006). "Immigration as a Colonial Inheritance: Post-Colonial Immigrants in the Netherlands, 1945–2002". Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 32 (3): 323–346. doi:10.1080/13691830600555210. S2CID 216142383.

- ^ Thanh-Dam, Truong; Gasper, Des (2011). Transnational Migration and Human Security: The Migration-Development-Security Nexus. Springer. p. 201.

- ^ a b Keasberry, Jeff (2012). Indische Keukengeheimen, recepten en verhalen van 3 generaties Keasberry's. Uithoorn: Karakter Uitgevers BV. p. 33. ISBN 978-90-452-0274-7.

- ^ a b C. Countess van Limburg Stirum, The Art of Dutch Cooking (Publisher: Andre Deutsch Limited, London, 1962) pp. 179-185

- ^ "Indo music in Europe". Rockabillyeurope.com. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ "storyofindorock.nl". www.storyofindorock.nl. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- ^ Willems, Wim Tjalie Robinson; Biografie van een Indo-schrijver (Publisher: Bert Bakker, 2008) ISBN 978-90-351-3309-9

- ^ Nieuwenhuys, Rob (1999). Mirror of the Indies: A History of Dutch Colonial Literature. Translated by E. M. Beekman. Periplus. ISBN 978-0870233685.

- ^ Boehmer, Elleke; de Mul, Sarah (2012). The Postcolonial Low Countries: Literature, Colonialism, and Multiculturalism. Lexington Books. pp. 100, 109.

- ^ Entzinger, H. (1995). "East and West Indian Migration to the Netherlands". The Cambridge Survey of World Migration.

- ^ "Dossier Karpaan (NCRV TV channel, 16-10-1961) Original video footage (Spijtoptanten)". geschiedenis24.nl. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ a b Iburg, Nora (2009). Van Pasar Malam tot I Love Indo, identiteitsconstructie en manifestatie door drie generaties Indische Nederlanders (Master thesis, Arnhem University) (in Dutch). Ellessy Publishers, 2010. ISBN 978-90-8660-104-2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ van Amersfoort, Hans Immigration as a colonial inheritance: post-colonial immigrants in the Netherlands, 1945-2002 (Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Commission for racial equality, 2006)

- ^ Willems, Wim Sporen van een Indisch verleden (1600-1942) (COMT, Leiden, 1994) ISBN 90-71042-44-8

- ^ Note: The Indo practice of taking frequent baths was considered extravagant by social workers as the Dutch at the time were accustomed to taking weekly baths only.

- ^ The academic definition in sociological studies often used to determine first-generation Indos: Indo repatriates who could consciousnessly make the decision to immigrate. As of age 12.

- ^ Crul, Lindo and Pang (1999). Culture, Structure and Beyond, Changing identities and social positions of immigrants and their children. Het Spinhuis Publishers. p. 37. ISBN 978-90-5589-173-3. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ "Indisch 3.0 - voor en door jongeren met Indische roots (2007 - 2014) | archiefsite over de Indische jongerencultuur".

- ^ Recent Dutch academic studies include:

Boersma, Amis, Agung. Indovation, de Indische identiteit van de derde generatie (Master thesis, Leiden University, Faculty Languages and cultures of South East Asia and Oceania, Leiden, 2003); De Vries, Marlene. Indisch is een gevoel, de tweede en derde generatie Indische Nederlanders Archived 17 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine (Amsterdam University Press, 2009) ISBN 978-90-8964-125-0; Vos, Kirsten Indie Tabe, Opvattingen in kranten van Indische Nederlanders in Indonesië over de repatriëring (Master Thesis, Media and Journalism, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Faculty of history and art, The Hague, 2007) "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Radio interview with K.Vos; Iburg, Nora Van Pasar Malam tot I Love Indo, identiteitsconstructie en manifestatie door drie generaties Indische Nederlanders[dead link] (Master thesis, Arnhem University, 2009, Ellessy Publishers, 2010) ISBN 978-90-8660-104-2 vanstockum.nl[permanent dead link] (in Dutch) - ^ Herself a third-generation Indo descendant

- ^ (in Dutch) Iburg, Nora Van Pasar Malam tot I Love Indo, identiteitsconstructie en manifestatie door drie generaties Indische Nederlanders[permanent dead link] (Master thesis, Arnhem University, 2009, Ellessy Publishers, 2010) p. 134 ISBN 978-90-8660-104-2

- ^ "Panel paper ASAA conference by Dr. Roger Wiseman, University of Adelaide". Archived from the original on 30 August 2007.

- ^ "Halin Website". Stichtinghalin.nl. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ (in Dutch) Alan Neys Memorial Fundraise Website. Retrieved 19 April 2010 Archived 24 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sari, Nursita (25 December 2017). "Ibadah Berbahasa Belanda Hanya Ada di GPIB Immanuel Jakarta". KOMPAS.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ "Depok - Haar geschiedenis en die van de familie Loen". depok.nl. 28 June 2024.

- ^ The Indo community of Tugu descend from the old Portuguese mestizo. Dutch newspaper article: 'Tokkelend hart van Toegoe', Maas, Michel (Volkskrant, 9 January 2009)

- ^ (in Indonesian) Online article (id) about the Blue Eyed People from Lanbo, Aceh, Sumatra Archived 18 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Jakarta Post article about the 'Portuguese Achenese' People from Lanbo, Aceh, Sumatra". Archived from the original on 23 June 2012.

- ^ "The last Portuguese-Acehnese of Lamno | the Jakarta Post". Archived from the original on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2006. Retrieved 13 August 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Santoso, Aboeprijadi. "Tsunami 10 years ago: The last Portuguese-Acehnese of Lamno (Feb. 2005)".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Home 1". Waspada Online.

- ^ "Indonesian language article on KUNCI Cultural Studies Website". Archived from the original on 9 July 2007.

Bibliography

- Bosma U., Raben R. Being "Dutch" in the Indies: a history of creolisation and empire, 1500–1920 (University of Michigan, NUS Press, 2008) ISBN 9971-69-373-9

- (in Dutch) Bussemaker, H. Th. Bersiap. Opstand in het Paradijs (Walburg Pers, Zutphen, 2005)

- Cooper, Frederick and Stoler, Ann Laura Tensions of empire: colonial cultures in a bourgeois world (Publisher: University of California Press, Berkeley, 1997), Googlebook

- (in Indonesian) Cote, Joost and Westerbeek, Loes. Recalling the Indies: Kebudayaan Kolonial dan Identitas Poskolonial, (Syarikat, Yogyakarta, 2004)

- Crul, Lindo and Lin Pang. Culture, Structure and Beyond, Changing identities and social positions of immigrants and their children (Het Spinhuis Publishers, 1999) ISBN 90-5589-173-8

- (in Dutch) De Vries, Marlene. Indisch is een gevoel, de tweede en derde generatie Indische Nederlanders. (Amsterdam University Press, 2009) ISBN 978-90-8964-125-0 Googlebook

- Gouda, F. American Visions of the Netherlands East Indies/Indonesia (Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2002)

- Krancher, Jan A. The Defining Years of the Dutch East Indies, 1942–1949 (McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers) ISBN 978-0-7864-1707-0

- (in German) Kortendick, Oliver. Indische Nederlanders und Tante Lien: eine Strategie zur Konstruktion ethnischer Identität (Master Thesis, Canterbury University of Kent, Social Anthropology, 1990) ISBN 0-904938-65-4

- Palmer and Colton. A History of the Modern World (McGraw-Hill, Inc. 1992) ISBN 0-07-557417-9

- Ricklefs, M. C. A History of Modern Indonesia Since c. 1300 (Stanford University Press, 2001).

- Schenkhuizen, M. Memoires of an Indo Woman (Edited and translated by Lizelot Stout van Balgooy), (Ohio University Press, no. 92 Athens, Ohio 1993)

- (in Indonesian) Soekiman, Djoko. Kebudayaan Indis dan gaya hidup masyarakat pendukungnya di Jawa (Unconfirmed Publisher, 2000) ISBN 979-8793-86-2

- Taylor, Jean Gelman. The Social World of Batavia: European and Eurasian in Dutch Asia (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1983) ISBN 978-0-300-09709-2

- Taylor, Jean Gelman. Indonesia: Peoples and Histories (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003). ISBN 0-300-09709-3

External links

- Assimilation Out:Europeans, Indo-Europeans and Indonesians seen through sugar from the 1880s to the 1950s

- Culture, structure and beyond

- Dutch East Indies, website dedicated to the Dutch-Indonesian community

- (in Dutch) 'Indie Tabe' Master Thesis Erasmus University by Kirsten Vos about the Indo repatriation (1950–1958)

- The Indo Project, dedicated to the preservation, promotion and celebration of Indo culture and history through education and raising public awareness

- Medical Journal: European Physicians and Botanists, Indigenous Herbal Medicine in the Dutch East Indies, and Colonial Networks of Mediation via Indo-European women Hans Pols, University of Sydney

- Eurasians: A Resource Guide