Indian Australians

Ratha Yatra procession in Brisbane | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 783,958 by ancestry (2021 census)[1] (3.1% of the Australian population)[1] 721,050 born in India (2020)[2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Melbourne, Sydney, Perth, Brisbane, Adelaide, Woolgoolga and Regional Victoria | |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| |

| Related ethnic groups | |

Indian Australians or Indo-Australians are Australians of Indian ancestry. This includes both those who are Australian by birth, and those born in India or elsewhere in the Indian diaspora. Indian Australians are one of the largest groups within the Indian diaspora, with 783,958 persons declaring Indian ancestry at the 2021 census, representing 3.1% of the Australian population.[1] In 2019, the Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated that 721,050 Australian residents were born in India.[3][4]

Indians are the youngest average age (34 years) and the fastest growing community both in terms of absolute numbers and percentages in Australia.[5]

In 2017–18 India was the largest source of new permanent annual migrants to Australia since 2016, and overall third largest source nation of cumulative total migrant population behind England and China, 20.5% or 33,310 out of 162,417 Australian permanent resident visas went to the Indians who also additionally had 70,000 students were studying in Australian universities and colleges, and Hindi (ranked 8th with 0.7% of total population) and Punjabi (ranked 10th with 0.6% of total population) are among the top 10 languages spoken in Australia.[6][7][8] Among Indian origin religions, which also include non-Indians, are Buddhist (2.4% of total population or 563,700 people), Hindus (1.9% or 440,300) and Sikhs (0.5% or 125,900).[7]

As of 2016, Indians were the highest educated migrant group in Australia with 54.6% of Indians in Australia having a bachelor's or higher degree, more than three times Australia's national average.[9]

The long history of Indian migration to Australia has progressed "from 18th-century sepoys and lascars (soldiers and sailors) aboard visiting European ships, through 19th-century migrant labourers and the 20th century's hostile policies to the new generation of skilled professional migrants of the 21st century... India became the largest source of skilled migrants in the 21st century."[10]

History

Pre-history migration of Indians (2300 BCE–2000 BCE)

A study of Indigenous Australian DNA has found that Indigenous Australians may have mixed with people of Indian origin about 4,200 years ago. The same study showed that flint tools and Indian dogs may have been introduced from India at about this time.[11] A 2012 paper reports that there is also evidence of a substantial genetic flow from India to northern Australia estimated at slightly over four thousand years ago, a time when changes in tool technology and food processing appear in the Australian archaeological record, suggesting that these may be related.[12] One genetic study in 2012 by Irina Pugach and colleagues at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology has suggested that about 4,000 years before the First Fleet landed in Australia (in 1788), some Indian explorers had settled in Australia and assimilated into the local population in roughly 2217 BC.[13] The study by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology found that there was a migration of genes from India to Australia around 2000 BCE. The researchers had two theories for this: either some Indians had contact with people in Indonesia who eventually transferred those genes from India to Aboriginal Australians, or that a group of Indians migrated all the way from India to Australia and intermingled with the locals directly.[14][15]

Indian connection with European exploration of Australia (1627–1787)

Most early explorations of Australia by various European colonial powers had an Indian connection. Indians had been employed for a long time on the European ships trading in Colonial India and the East Indies. Many of the early voyages to the Pacific either started or terminated in India and many of these ships were wrecked in the uncharted waters of the South Pacific.[16] In 1606, the Dutch East India Company's ship, Duyfken, led by Willem Janszoon, made the first documented European landing in Australia.[17] In 1627 the south coast of Australia was accidentally discovered by the Dutch East India Company explorer François Thijssen and named 't Land van Pieter Nuyts, in honour of the highest ranking passenger, Pieter Nuyts, extraordinary Councillor of India.[18][19] In 1628 a squadron of Dutch East India Company ships was sent by the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies Pieter de Carpentier to explore the northern coast. These ships made extensive examinations, particularly in the Gulf of Carpentaria, named in honour of de Carpentier.[20]

Alexander Dalrymple (1737–1808), the Examiner of Sea Journals for the British East India Company,[21] whilst translating some Spanish documents captured by Indian sepoys during the 1762 CE occupation of Philippines by the British India, found Portuguese navigator Luis Váez de Torres's testimony which led Dalrymple to discover and publish in 1770–1771 the existence of an unknown continent which he named as Terra Australis (or Southern Continent), this aroused widespread interest and prompted the British government in 1769 to order James Cook in HM Bark Endeavour to seek out the Southern Continent, which was discovered in June 1767 by Samuel Wallis in HMS Dolphin and named by him King George Island.[22] The London press reported in June 1768 that two ships would be sent to the newly discovered island and from there to "attempt the Discovery of the Southern Continent".[23] The British East India Trade Committee recommended in 1823 that a settlement be established on the coast of northern Australia to forestall the Dutch, and Captain J.J.G. Bremer, RN, was commissioned to form a settlement between Bathurst Island and the Cobourg Peninsula.[24]

Colonial era (1788–1900)

Indian immigration from British India to Australia began early in history of Australian colony. The first Indians arrived in Australia with the British settlers who had been living in India.[25]

The people of the first British fleet to establish a new colony, which landed on 26 January 1788, included seamen, marines and their families, government officials, and a large number of convicts, including women and children. All had been tried and convicted in Great Britain and almost all of them in England. However, many are known to have come to England from other parts of Great Britain and, especially, from Ireland; at least 12 were identified as black (born in India, Britain, Africa, the West Indies, North America, or a European country or its colony).[26]: 421–4 [27][28][29] In 1788, Indian crews from Bay of Bengal came to Australia on trading ships.[30] After establishment of first European colony in Sydney in Australia in 1788 by the colonial British Indian Empire under the British East India Company, the company had exclusive right on control of all trade to and from the penal colony.[31][32] These colonies multiplied and expanded to include whole Australia, various Islands in Oceania, initially colonies were established under the British Indian Empire including New Zealand which was administered as part of New South Wales until 1841.

Between 1788 and 1868 on board 806 ships in all about 164,000 convicts were transported to the Australian colonies, 1% were from the British outposts in India and Canada, Maoris from New Zealand, Chinese from Hong Kong and slaves from the Caribbean.[33] British colonial convict ships from Britain and elsewhere to Australia frequently stopped over in India, many of which were built in India, and among those ships with convicts started the initial sail from India include HMS Duchess of York which sailed from Bengal in India and arrived at Port Jackson on 4 April 1807 carrying merchandise and rice also transported two military convicts,[34] Hunter arrived on 20 August 1810, Indian arrived on 16 December 1810, Amboyna arrived in Australia on 1 January 1822,[35] Cawdry arrived on 1 January 1826 from India and Ceylon, Edward Lombes on 6 January 1833,[34] and Swallow arrived on 23 October 1836. Almorah sailed from Britain and stopped over at Madras and Bengal in 1818.[36]

In the late 1830s, more Indians started to arrive in Australia as indentured labourers when the penal transport of convicts to New South Wales (which at the time also consisted of Queensland and Victoria) was slowing, before being abolished altogether in 1840.[citation needed] The lack of manual labourers from the convict assignment system led to an increase demand for foreign labour, which was partly filled by the arrival of Indians who came from an agrarian background in India, and thus fulfilled their tasks as farm labourers on cane fields and shepherds on sheep stations well.[citation needed] In 1844, P. Friell who had previously lived in India, brought 25 domestic workers from India to Sydney and these included a few women and children.[37] Among the earliest Indians was a Hindu Sindhi merchant, Shri Pammull, who after arrived in 1850s built a family opal trade in Melbourne which still prosperously continues with his fourth-generation descendants.[38] "Initially, the migrants from India were indentured labourers, who worked on sheep stations and farms around Australia. Some adventurers followed during the gold rush of the 1850s. A census from 1861 indicates that there were around 200 Indians in Victoria of whom 20 were in Ballarat, the town which was at the epicenter of the gold rush. Thereafter, many more came and worked as hawkers - going from house to house, town to town, traversing thousands of kilometers, making a living by selling a variety of products."[39][better source needed]

From the 1860s, Indians, most of them Sikh, worked as merchants, industrialists, and businessmen to operate throughout outback Australia, as 'pioneers of the inland'.[40] The 1881 census records 998 people who were born in India but this had grown to over 1700 by 1891.[25]

Between 1860s to 1900 period when small groups of cameleers were also shipped in and out of Australia at three-year intervals, to service South Australia's inland pastoral industry by carting goods and transporting wool bales by camel trains, who were commonly referred to as "Afghans" or "Ghans", despite their origin often being mainly from British India, and some even from Afghanistan and Egypt and Turkey.[41] Majority of cameleers, including Indian cameleers, were Muslims with a sizeable minority were Sikhs from Punjab region, they set up camel-breeding stations and rest house outposts, known as caravanserai, throughout inland Australia, creating a permanent link between the coastal cities and the remote cattle and sheep grazing stations until about the 1930s, when they were largely replaced by the automobile.[41]

Since Federation (1901–present)

During the White Australia policy

From federation in 1901 until the 1960s, immigration of non-Europeans, including Indians, into Australia was restricted due to the enactment of the White Australia policy. The laws made it impossible for Indians to enter the country unless they were merchants or students, who themselves were only allowed in for short periods of time. Historians place the number of Indians in Australia at federation in 1901 somewhere between 4700 and 7600.[42] According to the 1911 census, there was only 3698 'Indians' signifying a large decrease, with the trend continuing, with only approximately 2200 'Indians' in the country in 1921.[43] After 1901 Immigration Restriction Act was introduced by the Australian Government the migration [of non-white migrants] from India was curtailed, but following India's independence from Britain in 1947, the number of Indian-born Anglo-western white British citizens emigrating to Australia increased, along with migration of mixed race European-Indians, such as Anglo-Indians, Dutch Anglo-Indians and Portuguese Indians.[44][45] The 1901 Immigration Restriction Act, one of the first laws passed by the new Australian parliament, which was the centrepiece of the White Australia Policy aimed to restrict immigration from Asia, where the population was vastly greater and the standard of living vastly lower and was similar to measures taken in other settler societies such as the United States, Canada and New Zealand.[46] While Labor Party wanted to protect "white" jobs and pushed for clearer restrictions, Free Trade Party's MP Bruce Smith said he had "no desire to see low-class Indians, Chinamen or Japanese...swarming into this country... But there is obligation...not (to) unnecessarily offend the educated classes of those nations".[47]

During World War I (1914–1918) Indian and Australian troops were deployed together in several sectors, including in Europe, Middle East, Africa, Egypt and Turkey.[48][49][50] During Gallipoli Campaign the Australians and New Zealanders troops were deployed to take part in the operation, although they were outnumbered by the British, Indian and French contingents, a fact which is often overlooked today by many Australians and New Zealanders.[51] Australian nurses also staffed 10 British colonial hospitals in India.[48]

During World War II (1939–1945) the hundreds of Australians were posted to British units in Burma and India.[52] Hundreds of Australians also served with RAF units in India and Burma, and in May 1943 330 Australians were serving in forty-one squadrons in India, of which only nine had more than ten Australians.[53] In addition, many of the RAN's corvettes and destroyers served with the British Eastern Fleet where they were normally used to protect convoys in the Indian Ocean from attacks by Japanese and German submarines.[54]

Under multiculturalism

The end of White Australia policy saw a boom in migration of middle-class skilled professionals, by 2016 over 2 in every 3 migrants who arrived were skilled professionals mainly from India, UK, China, South Africa and Philippines, "to work as doctors and nurses, human-resources and marketing professionals, business managers, IT specialists, and engineers...who were not fleeing war or poverty. The Indians in Australia are predominantly male, while the Chinese are majority female." Indians are the largest migrant ethnic group in Melbourne and Adelaide, fourth largest in Brisbane, and likely to jump from third place to second place in Sydney by 2021. In Melbourne, the suburbs of Docklands, Footscray, Sunshine, Truganina, Tarneit and Pakenham have higher concentration of Indians specially the students. In Sydney, Parramatta [and neighbouring suburbs such as Harris Park and Westmead, etc.] have higher concentration of migrants.[55] By 2019, the number of Indians grew at nine times the annual national average growth, and number of overseas student visas and post-study work visas also exploded.[56]

Between 2007 and 2010, the violence against Indians in Australia controversy took place, and a subsequent Indian Government investigation concluded that, of 152 reported racially motivated assaults against Indian students in Australia in 2009, 23 involved racial overtones.[57] In the year 2007–2008, 1,447 Indians had been victims of crime including assaults and robberies in the state of Victoria in Australia.[58] In either case, the Victorian police refused to release the data for public scrutiny, the stated reason being that it was "problematic: as well as 'subjective and open to interpretation'".[59] Indian media have accused the Australian authorities of being denialist.[60] On 9 June 2009, Indian Prime Minister, addressing the Indian Parliament said that "he was 'appalled' by the senseless violence and crime, some of which are racist in nature,"[61] Indian students held protests in Melbourne and Sydney,[62][63] which were sparked by an earlier attack on Indians by Lebanese Australian men.[64]

Demographics

783,958 persons declared Indian ancestry (whether alone or in combination with another ancestry) at the 2021 census, representing 3.1% of the Australian population.[1]

In 2019, the Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated that 721,050 Australian residents were born in India.[3][65]

At the 2021 census the states with the largest number of people nominating Indian ancestry were: New South Wales (350,770), Victoria (250,103), Queensland (93,648), Western Australia (77,357) and South Australia (43,598).[66]

In 2009 there were an additional 90,000 Indian students studying at Australian tertiary institutions according to Prime Minister Rudd.[67]

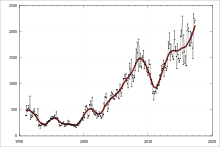

Historical population trends

This table only reflects the people who were born in India, and not all the people who have the Indian ancestry such as the second generation Indian Australians or the first generation Indian Australians from Indian diaspora nations e.g. Fiji, Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Suriname, Guyana, etc. Prior to 1947 India's Independence and simultaneous partition, the Pakistani Australian and Bangladeshi Australian as nations did not exist as these were part of British India, hence these are also included in the demography of Australian Indians till 1947.

| Year | Born in India | All overseas born | Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % of Indians among overseas born | Number | % of all overseas born in total population of Australia | and comments | ||

| 26 January 1788[26][27][28][29] | 12* | People of the first British fleet included 12 non-European people including some Indians. | ||||

| 1881[25] | 998 | |||||

| 1891[25] | 1700 | |||||

| 1901[42] | 4700 to 7600 | Introduction of White Australia policy led to reduction of Indians. | ||||

| 1911[43] | 3698 | |||||

| 1921[43] | 2200 | |||||

| Before 1941[68] | 170 | 0.1 | 16,681 | 0.3 | ||

| 1941–1950[68] | 2,027 | 0.7 | 106,647 | 2.0 | ||

| 1951–1960[68] | 1,697 | 0.6 | 375,076 | 7.1 | ||

| 1961–1970[68] | 10,319 | 3.5 | 642,355 | 12.1 | End of the White Australia policy in 1973. | |

| 1971–1980[68] | 11,595 | 3.9 | 571,828 | 10.8 | ||

| 1981–1990[68] | 17,659 | 6.0 | 782,926 | 14.8 | ||

| 1991–2000[68] | 36,765 | 12.4 | 786,777 | 14.9 | ||

| 2001–2005[68] | 48,949 | 16.6 | 581,597 | 11.0 | ||

| 2006–2011[68] | 159,326 (390,894) | 52.9 | 1,190,322 | 22.5 | 390,894 are ethnic Indian and among them 295,362 were born in India. | |

| 2011–2016[3][5][69] | 592,000 (619,164) | 619,164 (2.8% of Australian population) are ethnic Indian and among them 592,000 (2.4% of Australian population) were born in India. | ||||

| 2016–2021 | ||||||

| 2022–2027 | ||||||

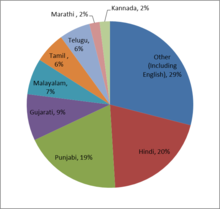

Indian languages

Hindi and Punjabi languages, with 159,652 and 132,496 speakers, are among top 10 language spoken at home in Australia. Other Indian languages and their respecting speaker in Australia are Tamil (73,161), Bengali (54,566), Malayalam (53,206), Gujarati (52,888), Telugu (34,435), Marathi (13,055), Kannada (9,701), Konkani (2,416), Sindhi (1,592), Kashmiri (215), and Odia (721).[6] Number of Hindi speakers by state in 2018, were NSW (67,034), Victoria (51,241), Queensland (18,163), Western Australia (10,747), South Australia (7,310), ACT (3,646), NT (852), and Tasmania (639).[7] 81% of Punjabi speakers are Sikhs, 13.3% are Hindus and 1.4% are Muslims.[70]

Religion

With 92.6% of Indian Australians being religious, Indian Australians are a much more religious group than Australia as a whole (Australia being 46.1% irreligious),[72][73] but less religious than India itself which is 99.7% religious.[74] While India is 79.8% Hindu, 14.2% Muslim, 2.3% Christian, and 1.7% Sikh, Indian Australians are 45.0% Hindu, 20.8% Sikh, 10.3% Catholic, and 6.6% Muslim, with a significant over-representation of Sikhs and Christians and an under-representation of Hindus and Muslims.

Socio-economic status

In 2016, it was revealed 54.6% of Indian migrants in Australia hold a bachelor's degree or a higher educational degree, more than three times Australia's national average of 17.2% in 2011, making them the most educated demographic group in Australia.[9]

India annually contributes the largest number of migrants to both Australia and New Zealand. According to census figures from 2016, among India-born residents in Australia, the median income was $785, higher than the corresponding figure for all overseas-born residents at $615, and all Australia-born residents at $688.[75]

In popular media

"Indians and the Antipodes: Networks, Boundaries and Circulation" 2018 book edited by Sekhar Bandyopadhyay and Jane Buckingham "is the first book that seeks to juxtapose histories of Indian migration to Australia and New Zealand in a comparative framework to show their interconnectedness as well as dissimilarities. Side by side with stories of collective suffering and struggles of the diaspora, it focuses on individual resilience, enterprise and social mobility. It analyses 'White Australia' and 'White New Zealand' policies of the early twentieth century to point to their interconnected histories. It also looks critically at the more recent migration, its changing nature and the challenges it poses to both the migrant communities and the host societies."[76]

Notable Indian Australians

Indian ancestry

- Anupam Sharma, Filmmaker, Australia Day Ambassador, film entrepreneur

- Astra Sharma, Tennis player

- Aravind Adiga, Novelist, winner of the 2008 Man Booker Prize

- Purushottama Bilimoria, Professor at Deakin University

- Anusha Dandekar, Actress

- Shibani Dandekar, Actress

- Chennupati Jagadish AC, pioneer in nanotechnology

- Zinnia Kumar Scientist and International Fashion Model

- Kersi Meher-Homji, Journalist and Author

- Mahesh Jadu, Actor

- Maria Thattil, Activist, Beauty Queen and Model of South Indian descent who was crowned Miss Universe Australia 2020 and placed Top 10 at Miss Universe 2020

- Marc Fennell, film critic, technology journalist, radio personality, author and television presenter

- Tharini Mudaliar, Singer and Actress who played a role in The Matrix Revolutions and Xena: Warrior Princess

- Indira Naidoo, Newsreader

- Neel Kolhatkar, Comedian

- Pankaj Oswal, controversial businessman, accused of embezzlement

- Vimala Raman, Actress

- Chandrika Ravi, Actress

- Pallavi Sharda, Actress

- Partho Sen-Gupta, Filmmaker

- Lisa Sthalekar, Captain of Australia Women's cricket team

- Mathai Varghese, Mathematician and Professor at the University of Adelaide

- Peter Varghese, Diplomat and Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Australia)

- Akshay Venkatesh, Mathematician

- Kaushaliya Vaghela, former Victorian politician, community leader.

- Guy Sebastian, Winner of 2003 Australian Idol, Singer and Songwriter

- Isha Sharvani, Bollywood actress

- Khoda Patel, member of the Northern Territory Legislative Assembly

- Jinson Charls, member of the Northern Territory Legislative Assembly

European–Indian ancestry

- Prue Car, ALP MP for Londonderry in New South Wales

- Christabel Chamarette, Senator from Western Australia from 1992 to 1996

- Stuart Clark, Australian Cricketer

- Chris Crewther, former Liberal MP for Dunkley

- Samantha Downie, Australia's Next Top Model Contestant, Model

- Jeremy Fernandez, ABC weekend presenter and reporter

- Lisa Haydon, Bollywood Actress

- Samantha Jade, Singer, Songwriter and Actress

- Sam Kerr, Footballer

- Daniel Kerr, Australian rules footballer

- Roger Kerr, Australian rules footballer

- Jordan McMahon, Australian rules footballer

- Lauren Moss, ALP MP for Casuarina in the Northern Territory

- Clancee Pearce, Australian Rules Footballer for Fremantle Football Club

- Eric Pearce, former Hockey Player who represented Australia in 4 Olympics

- Julian Pearce, former Hockey Player who represented Australia in 45 international matches

- Rex Sellers, Cricketer and Leg Spinner who played for Australia in India in 1964

- Dave Sharma, former Liberal MP for Wentworth

- Lisa Singh, former ALP Senator representing Tasmania

- Terry Walsh, Australian Hockey Player and Coach

- Anne Warner, former Minister for Aboriginal and Islander Affairs, Queensland Labor Government

- Rhys Williams, Professional footballer

In fiction

- Chloe Frazer, character from the Uncharted video game series.

See also

- Australia–India relations

- Fijian-Indian Australians

- India Now, an Australian TV program focused on Indian topics

- Non-resident Indian and person of Indian origin

- Pakistani Australians

- Bangladeshi Australians

- Punjabi Australians

- Australian Sikh Heritage Trail

- Man Mohan Singh (pilot)

- Romani people in Australia

References

- ^ a b c d "General Community Profile" (XLS). 2021 Census of Population and Housing. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ "Table 5.1 Estimated resident population, by country of birth(a), Australia, as at 30 June, 1996 to 2020(b)(c)". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ a b c "2016 Census Community Profiles: Australia". quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au. Archived from the original on 20 April 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ "Table 5.1 Estimated resident population, by country of birth(a), Australia, as at 30 June, 1996 to 2020(b)(c)". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ a b Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of (28 April 2020). "Main Features - Australia's Population by Country of Birth". www.abs.gov.au.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Indian population in Australia increases 30 per cent in less than two years; now the third largest migrant group in Australia, SBS, 2 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Hindi is the top Indian language spoken in Australia, SBS, 26 October 2018.

- ^ Migration program report for 2017–18

- ^ a b "Indians found to be Australia's most highly educated migrants - Interstaff Migration". 19 August 2016.

- ^ The story of the Indian diaspora in Australia and New Zealand is 250 years old, qz.com, 30 October 2018.

- ^ Creagh, Sunanda (15 January 2013). "Study links ancient Indian visitors to Australia's first dingoes". The Conversation. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ Manfred, K; Mark, S; Irina, P; Frederick, O; Ellen, G (14 January 2013). "Genome-wide data substantiate Holocene gene flow from India to Australia". PNAS. 110 (5): 1803–1808. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.1803P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211927110. PMC 3562786. PMID 23319617., pp. 1803–1808.

- ^ "An Antipodean Raj". The Economist. 19 January 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ Sanyal, Sanjeev (2016). The ocean of churn : how the Indian Ocean shaped human history. Gurgaon, Haryana, India. p. 59. ISBN 9789386057617. OCLC 990782127.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ MacDonald, Anna (15 January 2013). "Research shows ancient Indian migration to Australia". ABC News.

- ^ Davidson, J.W. (1975). Peter Dillon of Vanikoro: Chevalier of the South Seas. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-19-550457-7.

- ^ J.P. Sigmond and L.H. Zuiderbaan (1979) Dutch Discoveries of Australia. Rigby Ltd, Australia. pp. 19–30 ISBN 0-7270-0800-5

- ^ "NUYTS TERCENTENARY". The Register. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 24 May 1927. p. 11. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ Klaassen, Nic. "Nuyts, Pieter (1598–1655)". Nuyts, Pieter. Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ "INTERESTING HISTORICAL NOTES". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas.: National Library of Australia. 9 October 1923. p. 5. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ^ Howard T. Fry, Alexander Dalrymple (1737–1808) and the Expansion of British Trade, London, Cass for the Royal Commonwealth Society, 1970, pp. 229–230.

- ^ Andrew Cook, Introduction to An account of the discoveries made in the South Pacifick Ocean / by Alexander Dalrymple; first printed in 1767, reissued with a foreword by Kevin Fewster and an essay by Andrew Cook, Potts Point (NSW), Hordern House Rare Books for the Australian National Maritime Museum, 1996, pp. 38–9.

- ^ The St. James's Chronicle, 11 June and The Public Advertiser, 13 June 1768.

- ^ Historical Records of Australia, Series III, Vol. V, 1922, pp. 743–47, 770.

- ^ a b c d "Indian hawkers". museumvictoria.com.au. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ a b Gillen, Mollie (1989). The Founders of Australia: a Biographical Dictionary of the First Fleet. Sydney: Library of Australian History. ISBN 978-0908120697.

- ^ a b "1788". Objects through Time. NSW Migration Heritage Centre. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ a b Pybus, Cassandra (2006). Black Founders: the unknown story of Australia's first Black settlers. Sydney: UNSW Press. ISBN 9780868408491. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ a b Jupp, James, ed. (1988). The Australian People: an Encyclopedia of the Nation, its People and their Origins. North Ryde: Angus & Robertson. pp. 367–79. ISBN 978-0207154270.

- ^ "An introduction to HINDUISM in Australia | Fact sheet". Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ Binney, Keith R., Horsemen of the First Frontier (1788-1900) and The Serpents Legacy.

- ^ British East India Company in early Australia, tbheritage.com, accessed 11th February 2024.

- ^ "Convicts and the British colonies in Australia". Archived from the original on 12 October 2007.

- ^ a b "NRS 1155: Musters and other papers relating to convict ships". State Archives of NSW. 11 January 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ Phipps (1840), John Phipps (of the Master Attendant's Office, Calcutta) (1840) A Collection of Papers Relative to Ship Building in India ...: Also a Register Comprehending All the Ships ... Built in India to the Present Time .... (Scott). (Google eBook), p. 117 and 180.

- ^ British Library: Almorah.

- ^ "Indian overseas Population - Indians in Australia. Non-resident Indian and Person of Indian Origin". NRIOL.

- ^ "Hinduism / Hinduism by country / Hinduism in australia". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ Early Sikhs in Australia, SikhChic.com.

- ^ "Changing Face of early Australia". Australia.gov.au. 13 February 2009. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ a b australia.gov.au > About Australia > Australian Stories > Afghan cameleers in Australia Archived 5 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 8 May 2014.

- ^ a b Deacon, Desley; Russell, Penny; Woollacott, Angela, eds. (2008). Transnational Ties: Australian Lives in the World. ANU Press. doi:10.22459/TT.12.2008. ISBN 9781921536205.

- ^ a b c Jupp, James (October 2001). The Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, Its People and Their Origins. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521807890.

- ^ "Indiaoz Indian Arts & Literature - Indian Immigration & Australia". www.indiaoz.com.au. Archived from the original on 10 August 2007.

- ^ "Australia immigration - More Immigration from India". workpermit.com. 21 January 2005. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Alan Fenna, "Putting the 'Australian Settlement' in Perspective", Labour History 102 (2012)

- ^ Bruce Smith (Free Trade Party) Parliamentary Debates cited in D.M. Gibb (1973) The Making of White Australia. p. 113. Victorian Historical Association. ISBN

- ^ a b Bean, Charles (1946). Anzac to Amiens. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. ISBN 0-14-016638-6., pp.188, 516–517.

- ^ Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey; Morris, Ewan; Robin Prior (1995). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History (1st ed.). Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-553227-9., pp 67–68.

- ^ Stephens, Alan (2006). The Royal Australian Air Force: A History. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-555541-4., pp. 5–8.

- ^ Grey, Jeffrey (2008). A Military History of Australia (3rd ed.). Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69791-0., p. 93.

- ^ "Far Flung Australians". Australia's War 1939–1945. Archived from the original on 1 September 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2007. see also Andrews, Eric (1987). "Mission 204: Australian Commandos in China, 1942". Journal of the Australian War Memorial (10). Canberra: Australian War Memorial: 11–20. ISSN 0729-6274.

- ^ Long, Gavin (1973). The Six Years' War. A Concise History of Australia in the 1939–1945 War. Canberra: The Australian War Memorial and the Australian Government Printing Service. ISBN 0-642-99375-0.. p. 369.

- ^ "The Far East". Australia's War 1939–1945. Archived from the original on 4 August 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ^ Australasia rising: who we are becoming, The Sydney Morning herald, 2 January 2019.

- ^ "We're not Asia's 'white trash' but we must be careful", The Australian, 10 September 2019.

- ^ "Only 23 of 152 Oz attacks racist, Ministry tells LS". Indian Express. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ^ Lauren Wilson (21 January 2010). "Simon Overland admits Indians are targeted in attacks". The Australian. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ Sushi Das (13 February 2010). "The politics of violence". The Age, Melbourne. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ^ "Race horror: Assailants walk free". Archived from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ^ PM 'appalled' at attacks on Indian students in Australia Hindustan Times, 9 June 2009.

- ^ Thousands rally against racism in Melbourne – Times of India

- ^ Morello, Vincent (7 June 2009). "Indian student rally calls for equality". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 8 June 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- ^ "Indians in Australia say Lebanese youths behind attacks". The Times of India. 12 June 2009. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

- ^ "Table 5.1 Estimated resident population, by country of birth(a), Australia, as at 30 June, 1996 to 2020(b)(c)" (XLS). Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing: Cultural diversity data summary, 2021" (XLS). Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ "Archived copy". www.skynews.com.au. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Indians in Australia historic population trend, https://www.abs.gov.au, 2012.

- ^ Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of (28 June 2017). "Main Features - Cultural Diversity Article". www.abs.gov.au.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Census reveals rise of Indians in Australia | Indian Herald". Archived from the original on 12 June 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ "Cultural diversity of Australia". Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ "Australian Bureau of Statistics : 2021 Census of Population and Housing : General Community Profile" (XLSX). Abs.gov.au. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "Religious affiliation in Australia | Australian Bureau of Statistics". 7 April 2022.

- ^ "India has 79.8% Hindus, 14.2% Muslims, says 2011 census data on religion". Firstpost. 26 August 2016. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ^ "India-born Community Information Summary" (PDF). 2016.

- ^ Indians and the Antipodes: Networks, Boundaries, and Circulation.