In situ

In situ[a] is a Latin phrase meaning "in place" or "on site", derived from in ("in") and situ (ablative of situs, "place").[3] The term refers to the examination or preservation of phenomena within their original place or context. This methodological approach, used across diverse disciplines, maintains contextual integrity essential for accurate analysis. Conversely, ex situ methods examine subjects outside their original context.

The natural sciences frequently implement in situ methodologies. Geological studies employ field analysis of soil composition and rock formations, while environmental science relies on direct ecosystem monitoring to obtain accurate environmental data. Biological field research examines organisms in their natural habitats, revealing behavioral patterns and ecological interactions that laboratory settings cannot replicate. In chemistry and experimental physics, in situ techniques enable the observation of substances and reactions under native conditions, facilitating the documentation of dynamic processes.

In situ applications extend to various applied sciences as well. Aerospace industry implements on-site inspection protocols and monitoring systems for operational evaluation without system interruption. In medical terminology, particularly oncology, in situ designates early-stage cancers that remain confined to their point of origin. This diagnostic classification—indicating no invasion of adjacent tissues—serves as a determinant for treatment protocols and prognostic assessment. Space exploration utilizes in situ planetary research methods, conducting direct observational studies and data collection on celestial bodies, thereby avoiding the complexities inherent in sample-return missions.

The humanities, notably archaeology, employ in situ methodologies to maintain contextual authenticity. Archaeological investigations preserve the spatial relationships and environmental conditions of artifacts at excavation sites, enabling more precise historical analysis. In art theory and practice, the in situ principle guides both creation and exhibition. Site-specific artworks, such as environmental sculptures or architectural installations, demonstrate deliberate integration with their designated locations. This contextual placement establishes a methodological framework that emphasizes the relationship between artistic works and their environmental or cultural settings.

Aerospace industry

In aerospace structural health monitoring, in situ inspection denotes diagnostic methodologies that evaluate components within their operational environments—eliminating the need for disassembly or service interruption. The nondestructive testing (NDT) techniques employed for in situ damage detection include: infrared thermography, which measures thermal emissions to identify structural anomalies; speckle shearing interferometry (also known as shearography), which analyzes surface deformation patterns; and ultrasonic testing, which uses sound wave propagation to detect internal defects in composite materials.[4] Each technique exhibits characteristic operational constraints. Infrared thermography exhibits reduced effectiveness on low-emissivity materials,[5] shearography requires carefully controlled environmental conditions,[6] and ultrasonic testing protocols can be time-intensive for large structural components.[7] Nevertheless, the systematic integration of these complementary methodologies substantially enhances overall diagnostic capabilities.[4]

An additional approach involves the use of alternating current (AC) and direct current (DC) sensor arrays in real-time monitoring applications, facilitating in situ detection of structural degradation phenomena—including matrix discontinuities, interlaminar delaminations, and fiber fracture mechanisms—through quantitative analysis of electrical resistance and capacitance variations within composite laminate configurations.[4]

Archaeology

In archaeological methodology, the term in situ designates artifacts and other materials that maintain their original depositional context, undisturbed since their initial deposition. The systematic documentation of spatial coordinates, stratigraphic position, and associated matrices of in situ materials enables the reconstruction of historical processes and cultural practices. While artifacts frequently require extraction for analytical purposes, archaeological features—including hearths, postholes, and architectural foundations—necessitate comprehensive in situ documentation to preserve contextual data during stratigraphic excavation.[8]: 121 Documentation protocols encompass multiple recording methodologies: detailed field notation, scaled technical drawings, cartographic representation, and high-resolution photographic documentation. Contemporary archaeological practice incorporates advanced digital technologies, including 3D laser scanning, photogrammetry, unmanned aerial vehicles, and Geographic Information Systems (GIS), to capture complex spatial relationships.[9] Materials recovered from secondary contexts (ex situ), including those displaced through non-professional excavation activities, demonstrate diminished interpretive value; however, such assemblages may provide diagnostic indicators regarding the spatial distribution and typological characteristics of unexcavated in situ deposits, thereby informing subsequent excavation plans.[10][11]

The Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage establishes mandatory principles for signatory states regarding underwater shipwrecks. Among its directives is the stipulation that in situ preservation constitutes the preferred methodological approach.[8]: 558 [12]: 13 This protocol derives from the distinct preservation conditions in underwater environments, where diminished oxygen levels and temperature stability facilitate long-term artifact preservation. The extraction of artifacts from these submerged environments and subsequent exposure to atmospheric conditions typically accelerates deterioration processes, most notably in the oxidation of ferrous materials.[12]: 5

In archaeological contexts involving burial sites, in situ documentation encompasses the systematic recording and cataloging of human remains in their original depositional positions, often within complex matrices that incorporate sediments, clothing, and other associated artifacts. Mass grave excavations exemplify the methodological challenges of maintaining in situ preservation, as the presence of multiple individuals, sometimes numbering in the hundreds, necessitates comprehensive documentation of spatial relationships and contextual elements prior to the determination of individual identification, causes of death, and other forensic parameters.[13]

Art

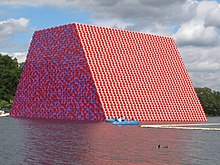

The concept of in situ in contemporary art emerged as a critical framework during the late 1960s and 1970s, designating artworks conceived and executed for specific spatial contexts. Such works incorporate the site's physical, historical, political, and sociological parameters as integral compositional elements.[14]: 160–162 This methodology stands in contrast to autonomous artistic production, wherein works maintain independence from their eventual display locations.[15] Theoretical discourse regarding the relevant artworks, particularly through the writings and practices of French conceptual artist and sculptor Daniel Buren, emphasized the dialectical relationship between artistic intervention and environmental context.[14]: 161

The site-specific installations of Christo and Jeanne-Claude serve as notable examples of applying in situ principles in art. Their architectural interventions, characterized by the systematic wrapping of built structures and landscape elements in textile materials, effected temporary spatial reconfigurations that altered public perception of established environments, as seen in The Pont Neuf Wrapped (1985) and Wrapped Reichstag (1995). The approach to in situ practice underwent further development through the land art movement, wherein practitioners such as Robert Smithson and Michael Heizer integrated their works directly into terrestrial environments, forging inextricable relationships between artistic intervention and geographical context.[15] Within contemporary aesthetic discourse, the term in situ has evolved into a theoretical construct, denoting artistic methodologies predicated on the essential unity of work and site.[14]: 160–161

Astronomy

A fraction of the globular star clusters in the Milky Way Galaxy, as well as those in other massive galaxies, might have formed in situ. The rest might have been accreted from now-defunct dwarf galaxies.

In astronomy, in situ also refers to in situ planet formation, in which planets are hypothesized to have formed at the orbital distance they are currently observed[16] rather than to have migrated from a different orbit (referred to as ex situ formation[17]).

Biology and biomedical engineering

In biology and biomedical engineering, in situ means to examine the phenomenon exactly in place where it occurs (i.e., without moving it to some special medium).

In the case of observations or photographs of living animals, it means that the organism was observed (and photographed) in the wild, exactly as it was found and exactly where it was found. This means it was not taken out of the area. The organism had not been moved to another (perhaps more convenient) location such as an aquarium.

This phrase in situ when used in laboratory science such as cell science can mean something intermediate between in vivo and in vitro. For example, examining a cell within a whole organ intact and under perfusion may be in situ investigation. This would not be in vivo as the donor is sacrificed by experimentation, but it would not be the same as working with the cell alone (a common scenario for in vitro experiments). For instance, an example of biomedical engineering in situ involves the procedures to directly create an implant from a patient's own tissue within the confines of the Operating Room.[18]

In vitro was among the first attempts to qualitatively and quantitatively analyze natural occurrences in the lab. Eventually, the limitation of in vitro experimentation was that they were not conducted in natural environments. To compensate for this problem, in vivo experimentation allowed testing to occur in the original organism or environment. To bridge the dichotomy of benefits associated with both methodologies, in situ experimentation allowed the controlled aspects of in vitro to become coalesced with the natural environmental compositions of in vivo experimentation.

In conservation of genetic resources, "in situ conservation" (also "on-site conservation") is the process of protecting an endangered plant or animal species in its natural habitat, as opposed to ex situ conservation (also "off-site conservation").[citation needed]

Chemistry and chemical engineering

In chemistry, in situ typically means "in the reaction mixture."

There are numerous situations in which chemical intermediates are synthesized in situ in various processes. This may be done because the species is unstable, and cannot be isolated, or simply out of convenience. Examples of the former include the Corey-Chaykovsky reagent and adrenochrome.

In biomedical engineering, protein nanogels made by the in situ polymerization method provide a versatile platform for storage and release of therapeutic proteins. It has tremendous applications for cancer treatment, vaccination, diagnosis, regenerative medicine, and therapies for loss-of-function genetic diseases.[19]

In chemical engineering, in situ often refers to industrial plant "operations or procedures that are performed in place." For example, aged catalysts in industrial reactors may be regenerated in place (in situ) without being removed from the reactors.

Civil engineering

In architecture and building, in situ refers to construction which is carried out at the building site using raw materials - as opposed to prefabricated construction, in which building components are made in a factory and then transported to the building site for assembly. For example, concrete slabs may be cast in situ (also "cast-in-place") or prefabricated.

In situ techniques are often more labour-intensive, and take longer, but the materials are cheaper, and the work is versatile and adaptable. Prefabricated techniques are usually much quicker, therefore saving money on labour costs, but factory-made parts can be expensive. They are also inflexible, and must often be designed on a grid, with all details fully calculated in advance. Finished units may require special handling due to excessive dimensions.

The phrase may also refer to those assets which are present at or near a project site. In this case, it is used to designate the state of an unmodified sample taken from a given stockpile.

Site construction usually involves grading the existing soil surface so that material is "cut" out of one area and "filled" in another area creating a flat pad on an existing slope. The term "in situ" distinguishes soil still in its existing condition from soil modified (filled) during construction. The differences in the soil properties for supporting building loads, accepting underground utilities, and infiltrating water persist indefinitely.

Computer science

A use of the term in-situ that appears in Computer Science focuses primarily on the use of technology and user interfaces to provide continuous access to situationally relevant information in various locations and contexts.[20][21] Examples include athletes viewing biometric data on smartwatches to improve their performance,[22] a presenter looking at tips on a smart glass to reduce their speaking rate during a speech,[23] or technicians receiving online and stepwise instructions for repairing an engine.

An algorithm is said to be an in situ algorithm, or in-place algorithm, if the extra amount of memory required to execute the algorithm is O(1),[24] that is, does not exceed a constant no matter how large the input. Typically such an algorithm operates on data objects directly in place rather than making copies of them.

For example, heapsort is an in situ sorting algorithm, which sorts the elements of an array in place. Quicksort is an in situ sorting algorithm, but in the worst case it requires linear space on the call stack (this can be reduced to log space). Merge sort is generally not written as an in situ algorithm.

AJAX partial page data updates is another example of in situ in a Web UI/UX context. Web 2.0 included AJAX and the concept of asynchronous requests to servers to replace a portion of a web page with new data, without reloading the entire page, as the early HTML model dictated. Arguably, all asynchronous data transfers or any background task is in situ as the normal state is normally unaware of background tasks, usually notified on completion by a callback mechanism.

With big data, in situ data would mean bringing the computation to where data is located, rather than the other way like in traditional RDBMS systems where data is moved to computational space.[25] This is also known as in-situ processing.

Design and advertising

In design and advertising the term typically means the superimposing of theoretical design elements onto photographs of real world locations. This is a pre-visualization tool to aid in illustrating a proof of concept.[citation needed]

Earth, ocean and atmospheric sciences

In physical geography and the Earth sciences, in situ typically describes natural material or processes prior to transport. For example, in situ is used in relation to the distinction between weathering and erosion, the difference being that erosion requires a transport medium (such as wind, ice, or water), whereas weathering occurs in situ. Geochemical processes are also often described as occurring to material in situ.

In oceanography and ocean sciences, in situ generally refers to observational methods made by obtaining direct samples of the ocean state, such as that obtained by shipboard surveying using a lowered CTD rosette that directly measure ocean salinity, temperature, pressure and other biogeochemical quantities like dissolved oxygen. Historically a reversing thermometer would be used to record the ocean temperature at a particular depth and a Niskin or Nansen bottle used to capture and bring water samples back to the ocean surface for further analysis of the physical, chemical or biological composition.

In the atmospheric sciences, in situ refers to obtained through direct contact with the respective subject, such as a radiosonde measuring a parcel of air or an anemometer measuring wind, as opposed to remote sensing such as weather radar or satellites.

Economics

In economics, in situ is used when referring to the in place storage of a product, usually a natural resource. More generally, it refers to any situation where there is no out-of-pocket cost to store the product so that the only storage cost is the opportunity cost of waiting longer to get your money when the product is eventually sold. Examples of in situ storage would be oil and gas wells, all types of mineral and gem mines, stone quarries, timber that has reached an age where it could be harvested, and agricultural products that do not need a physical storage facility such as hay.

Electrochemistry

In electrochemistry, the phrase in situ refers to performing electrochemical experiments under operating conditions of the electrochemical cell, i.e., under potential control. This is opposed to doing ex situ experiments that are performed under the absence of potential control. Potential control preserves the electrochemical environment essential to maintain the double layer structure intact and the electron transfer reactions occurring at that particular potential in the electrode/electrolyte interphasial region.

Environmental remediation

In situ can refer to where a clean up or remediation of a polluted site is performed using and stimulating the natural processes in the soil, contrary to ex situ where contaminated soil is excavated and cleaned elsewhere, off site.

Experimental physics

In transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM), in situ refers to the observation of materials as they are exposed to external stimuli within the microscope, under conditions that mimic their natural environments. This enables real-time observation of material behavior at the nanoscale. External stimuli in in situ TEM/STEM experiments include mechanical loading and pressure, temperature changes, electrical currents (biasing), radiation, and environmental factors—such as exposure to gas, liquid, and magnetic field—or any combination of these. These conditions allow researchers to study atomic-level processes such as phase transformations, chemical reactions, or mechanical deformations, providing insights into material behavior and properties essential for advancements in materials science.[26][27]

Experimental psychology

In psychology experiments, in situ typically refers to those experiments done in a field setting as opposed to a laboratory setting.

Gastronomy

In gastronomy, "in situ" refers to the art of cooking with the different resources that are available at the site of the event. Here a person is not going to the restaurant, but the restaurant comes to the person's home.[28]

Law

In legal contexts, in situ is often used for its literal meaning. For example, in Hong Kong, in-situ land exchange refers to a mechanism where landowners can swap their existing or expired leases with new grants for the same land parcel. This approach facilitates redevelopment while preserving the property's original location.[29]

In the field of recognition of governments under public international law the term in situ is used to distinguish between an exiled government and a government with effective control over the territory, i.e. the government in situ.

Linguistics

In linguistics, specifically syntax, an element may be said to be in situ if it is pronounced in the position where it is interpreted. For example, questions in languages such as Chinese have in situ wh-elements, with structures comparable to "John bought what?" with what in the same position in the sentence as the grammatical object would be in its affirmative counterpart (for example, "John bought bread"). An example of an English wh-element that is not in situ (see wh-movement): "What did John buy?"

Literature

In literature in situ is used to describe a condition. The Rosetta Stone, for example, was originally erected in a courtyard, for public viewing. Most pictures of the famous stone are not in situ pictures of it erected, as it would have been originally. The stone was uncovered as part of building material, within a wall. Its in situ condition today is that it is erected, vertically, on public display at the British Museum in London, England.[citation needed]

Medicine

The term in situ in the medical context is part of a group of two-word Latin expressions, including in vitro, in vivo, and ex vivo. Similar to abbreviations, these terms support the concise transfer of essential information in medical communication. In situ, specifically, is among the most widely used and versatile Latin terms in medical discourse in modern times.[30]

In oncology, in situ is commonly applied in the context of carcinoma in situ (CIS), a term describing abnormal cells confined to their original location without invasion of surrounding tissue.[30][31] CIS is a critical term in early cancer diagnosis, as it signifies a non-invasive stage, allowing for more targeted interventions before potential progression. Similarly, melanoma in situ is an early, localized form of melanoma, a type of malignant skin cancer. In this stage, the cancerous melanocytes—the pigment-producing cells that give skin its color—are confined to the epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin. The melanoma has not yet penetrated into the deeper dermal layers of the skin or metastasized to other parts of the body.[32]

Beyond oncology, in situ applies to fields that require maintenance of natural anatomical or physiological positions.[30] In orthopedic surgery, for example, the term describes procedures where orthopedic plates such as bone screws are placed without altering the original alignment of the bone, as in "[the patient] was treated operatively with an in situ cannulated hip screw fixation".[33]

Mining

In situ leaching or in situ recovery refers to the mining technique of injecting lixiviant underground to dissolve ore and bringing the pregnant leach solution to surface for extraction. Commonly used in uranium mining but has also been used for copper mining.[34]

Petroleum production

In situ refers to recovery techniques which apply heat or solvents to heavy crude oil or bitumen reservoirs beneath the Earth's crust. There are several varieties of in situ techniques, but the ones which work best in the oil sands use heat (steam).

The most common type of in situ petroleum production is referred to as SAGD (steam-assisted gravity drainage) this is becoming very popular in the Alberta Oil Sands.

RF transmission

In radio frequency (RF) transmission systems, in situ is often used to describe the location of various components while the system is in its standard transmission mode, rather than operation in a test mode. For example, if an in situ wattmeter is used in a commercial broadcast transmission system, the wattmeter can accurately measure power while the station is "on air."

Space science

Future space exploration or terraforming may rely on obtaining supplies in situ, such as previous plans to power the Orion space vehicle with fuel minable on the Moon. The Mars Direct mission concept is based primarily on the in situ fuel production using the Sabatier reaction, which produces methane and water from a reaction of hydrogen and carbon dioxide.

In the space sciences, in situ refers to measurements of the particle and field environment that the satellite is embedded in, such as the detection of energetic particles in the solar wind, or magnetic field measurements from a magnetometer.

Urban planning

In urban planning, in-situ upgrading is an approach to and method of upgrading informal settlements.[35]

Vacuum technology

In vacuum technology, in situ baking refers to heating parts of the vacuum system while they are under vacuum in order to drive off volatile substances that may be absorbed or adsorbed on the walls so they cannot cause outgassing.[citation needed]

Road assistance

The term in situ, used as "repair in situ", means to repair a vehicle at the place where it has a breakdown.

See also

- In situ conservation

- Ex situ conservation

- List of colossal sculptures in situ

- List of Latin phrases

- All pages with titles beginning with In situ

Notes

- ^ UK: /ɪn ˈsɪtjuː/ ⓘ, /ɪn ˈsɪtʃuː/; US: /ˌɪn ˈsaɪtjuː/, /ˌɪn ˈsɪtjuː/;[1] often not italicized in English[2]

References

- ^ "in situ, adv. & adj. 1648–". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2024. Retrieved 7 October 2024.

- ^ "4.21 Use of Italics", The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.), Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association, 2010, ISBN 978-1-4338-0562-2

- ^ Lewis & Short Latin Dictionary

- ^ a b c Addepalli, Sri; Roy, Rajkumar; Axinte, Dragoş; Mehnen, Jörn (2017). "'In-situ' Inspection Technologies: Trends in Degradation Assessment and Associated Technologies". Procedia CIRP. 59: 37. doi:10.1016/j.procir.2016.10.003.

- ^ "How Does Emissivity Affect Thermal Imaging?". Teledyne FLIR. 1 November 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ Yang, Lianxiang; Li, Junrui (2019). "Shearography". Handbook of Advanced Nondestructive Evaluation. pp. 383–384. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-26553-7_3. ISBN 978-3-319-26552-0.

- ^ Rizzo, P. (2022). "Sensing solutions for assessing and monitoring underwater systems". Sensor Technologies for Civil Infrastructures. pp. 362–363. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-102706-6.00018-0. ISBN 978-0-08-102706-6.

- ^ a b Renfrew, Colin; Bahn, Paul (2020). Archaeology: Theories, Methods and Practice (8th ed.). London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-29424-6.

- ^ Dimara, Asimina; Tsakiridis, Sotirios; Psarros, Doukas; Papaioannou, Alexios; Varsamis, Dimitrios; Anagnostopoulos, Christos-Nikolaos; Krinidis, Stelios (24 May 2024). "An Innovative System for Enhancing Archaeological In Situ Excavation through Geospatial Integration". Heritage. 7 (5): 2586–2619. doi:10.3390/heritage7050124.

- ^ Karl, Raimund (2 January 2019). "An empirical examination of archaeological damage caused by unprofessional extraction of archaeology ex situ ('looting'): A case study from Austria". Archäologische Denkmalpflege. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 24 October 2024 – via Bangor University.

- ^ Bynoe, Rachel; Ashton, Nick M.; Grimmer, Tim; Hoare, Peter; Leonard, Joanne; Lewis, Simon G.; Nicholas, Darren; Parfitt, Simon (24 February 2021). "Coastal curios? An analysis of ex situ beach finds for mapping new Palaeolithic sites at Happisburgh, UK". Journal of Quaternary Science. 36 (2): 191–210. Bibcode:2021JQS....36..191B. doi:10.1002/jqs.3270 – via CrossRef.

- ^ a b "The UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage". UNESCO Digital Library. UNESCO. 2007. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ Tuller, Hugh; Đurić’, Marija (January 2006). "Keeping the pieces together: Comparison of mass grave excavation methodology". Forensic Science International. 156 (2–3): 193. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.12.033. PMID 15896937.

- ^ a b c Verner, Lorraine (2024). "40. Site Specificity". In Barbanti, Roberto; Ginot, Isabelle; Solomos, Makis; Sorin, Cécile (eds.). Arts, Ecologies, Transitions: Constructing a Common Vocabulary. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781003852407. Retrieved 24 October 2024 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Riout, Denys (9 February 2014). "IN SITU (LATIN)". In Cassin, Barbara (ed.). Dictionary of Untranslatables: A Philosophical Lexicon. Princeton University Press. p. 484. ISBN 9781400849918.

- ^ Chiang, Eugene; Laughlin, Gregory (June 2013). "The minimum-mass extrasolar nebula: in situ formation of close-in super-Earths". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 431 (4): 3444–3455. arXiv:1211.1673. Bibcode:2013MNRAS.431.3444C. doi:10.1093/mnras/stt424.

- ^ D’Angelo, Gennaro; Bodenheimer, Peter (September 2016). "In Situ and Ex Situ Formation Models of Kepler 11 Planets". The Astrophysical Journal. 828 (1): 33. arXiv:1606.08088. Bibcode:2016ApJ...828...33D. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/828/1/33.

- ^ Krasilnikova, O.A.; Baranovskii, D.S.; Yakimova, A.O.; Arguchinskaya, N.; Kisel, A.; Sosin, D.; Sulina, Y.; Ivanov, S.A.; Shegay, P.V.; Kaprin, A.D.; Klabukov, I.D. (2022). "Intraoperative Creation of Tissue-Engineered Grafts with Minimally Manipulated Cells: New Concept of Bone Tissue Engineering In Situ". Bioengineering. 9 (11): 704. doi:10.3390/bioengineering9110704. ISSN 2306-5354. PMC 9687730. PMID 36421105.

- ^ Ye, Yanqi; Yu, Jicheng; Gu, Zhen (2015). "Versatile Protein Nanogels Prepared by In Situ Polymerization". Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics. 217 (3): 333–343. doi:10.1002/macp.201500296.

- ^ Ens, Barrett; Irani, Pourang (March 2017). "Spatial Analytic Interfaces: Spatial User Interfaces for In Situ Visual Analytics". IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications. 37 (2): 66–79. doi:10.1109/MCG.2016.38. PMID 28113834.

- ^ Willett, Wesley; Jansen, Yvonne; Dragicevic, Pierre (January 2017). "Embedded Data Representations" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics. 23 (1): 461–470. doi:10.1109/TVCG.2016.2598608. PMID 27875162.

- ^ Amini, Fereshteh; Hasan, Khalad; Bunt, Andrea; Irani, Pourang (2017). "Data representations for in-situ exploration of health and fitness data". Proceedings of the 11th EAI International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare. pp. 163–172. doi:10.1145/3154862.3154879. ISBN 978-1-4503-6363-1.

- ^ Tanveer, M. Iftekhar; Lin, Emy; Hoque, Mohammed (Ehsan) (2015). "Rhema: A Real-Time In-Situ Intelligent Interface to Help People with Public Speaking". Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces. pp. 286–295. doi:10.1145/2678025.2701386. ISBN 978-1-4503-3306-1.

- ^ Munro, J. Ian; Raman, Venkatesh; Salowe, Jeffrey S. (June 1990). "Stable in situ sorting and minimum data movement". BIT. 30 (2): 220–234. doi:10.1007/BF02017344.

- ^ Alves, Vladimir (August 2014). "In-Situ Processing Presentation" (PDF).

- ^ Sharma, Renu (2023). "Chapter 1. In-Situ TEM". In-Situ Transmission Electron Microscopy Experiments. p. 3. doi:10.1002/9783527834822.ch1. ISBN 978-3-527-34798-8.

- ^ Sharma, Renu; Yang, Wei-Chang David (8 April 2024). "Perspective and prospects of in situ transmission/scanning transmission electron microscopy". Microscopy. 73 (2): 79. doi:10.1093/jmicro/dfad057. PMID 38006307.

- ^ Gillespie, Cailein; Cousins, John A. (2001). European Gastronomy into the 21st Century. Oxford, UK: Elsevier. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-7506-5267-4. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ "DEVB Press Releases: Revised in-situ land exchange arrangements for Northern Metropolis to enhance speed and efficiency by leveraging market forces". devb.gov.hk. Development Bureau. 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2024.

- ^ a b c Lysanets, Yuliia V.; Bieliaieva, Olena M. (2018). "The use of Latin terminology in medical case reports: Quantitative, structural, and thematic analysis". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 12 (1): 45. doi:10.1186/s13256-018-1562-x. PMC 5824564. PMID 29471882.

- ^ "carcinoma in situ". NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms. National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ Massi, Guido; LeBoit, Philip E. (2013). "Chapter 28. Melanoma in Situ". Histological Diagnosis of Nevi and Melanoma. Springer. p. 421. ISBN 9783642373114 – via Google Books.

- ^ Kelly, Douglas W.; Kelly, Brian D. (2012). "A novel diagnostic sign of hip fracture mechanism in ground level falls: Two case reports and review of the literature". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 6: 136. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-6-136. PMC 3423009. PMID 22643013.

- ^ In Situ Leach (ISL) Mining of Uranium Archived 24 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine. world-nuclear.org

- ^ Huchzermeyer, Marie (2009). "The struggle for in situ upgrading of informal settlements: A reflection on cases in Gauteng". Development Southern Africa. 26 (1): 59–74. doi:10.1080/03768350802640099. S2CID 153687182.