Réunion

La Réunion

| |

|---|---|

| Motto(s): | |

Anthem:

| |

| |

| Coordinates: 21°06′52″S 55°31′57″E / 21.11444°S 55.53250°E | |

| Country | |

| Prefecture | Saint-Denis |

| Departments | 1 |

| Government | |

| • President of Regional Council | Huguette Bello (PLR) |

| • President of Departmental Council | Cyrille Melchior (LR) |

| Area | |

• Total | 2,511 km2 (970 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 15th region |

| Population (January 2024)[1] | |

• Total | 885,700 |

| • Density | 350/km2 (910/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Réunionese |

| GDP (in 2023) | |

| • Total | €23.2 billion |

| • Per capita | €26,300 |

| Time zone | UTC+04:00 (RET) |

| ISO 3166 code | |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Website | |

La Réunion (/riːˈjuːnjən/; French: [la ʁe.ynjɔ̃] ⓘ; Reunionese Creole: La Rényon; known as Île Bourbon before 1848) is an island in the Indian Ocean that is an overseas department and region of France. Part of the Mascarene Islands, it is located approximately 679 km (422 mi) east of the island of Madagascar and 175 km (109 mi) southwest of the island of Mauritius. As of January 2024, it had a population of 885,700.[1] Its capital and largest city is Saint-Denis.

La Réunion was uninhabited until French immigrants and colonial subjects settled the island in the 17th century. Its tropical climate led to the development of a plantation economy focused primarily on sugar; slaves from East Africa were imported as fieldworkers, followed by Malays, Vietnamese, Chinese, and Indians as indentured laborers. Today, the greatest proportion of the population is of mixed descent, while the predominant language is Réunion Creole, though French remains the sole official language.

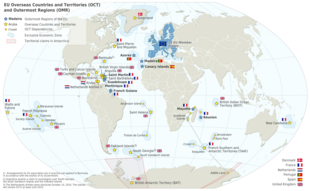

Since 1946, Réunion has been governed as a French region and thus has a similar status to its counterparts in Metropolitan France. Consequently, it is one of the outermost regions of the European Union and part of the eurozone;[3] it is, along with the French overseas department of Mayotte, one of the two eurozone areas in the Southern Hemisphere. Owing to its strategic location, France maintains a large military presence.

Name

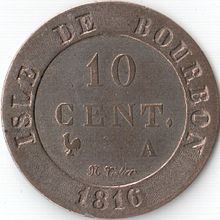

The French took possession of the island in the 17th century, naming it Isle Bourbon after the House of Bourbon which then ruled France. To break with this name, which was too attached to the Ancien Régime, the National Convention decided on 23 March 1793[5] to rename the territory Réunion Island. ("La Réunion", in French, usually means "meeting" or "assembly" rather than "reunion". This name was presumably chosen in homage to the meeting of the fédérés of Marseilles and the Paris National Guards that preceded the insurrection of 10 August 1792. No document establishes this and the use of the word "meeting" could have been purely symbolic.)[6]

The island changed its name again in the 19th century: in 1806, under the First Empire, General Decaen named it Isle Bonaparte (after Napoleon), though in 1810 it became Isle Bourbon again. It was eventually renamed Réunion after the fall of the July monarchy by a decree of the provisional government on 7 March 1848.[7]

In accordance with the original spelling and the classical spelling and typographical rules,[8] "la Réunion" was written with a lower case in the article, but during the end of the 20th century the spelling "La Réunion" with a capital letter was developed in many writings to emphasize the integration of the article in the name. This last spelling corresponds to the recommendations of the Commission nationale de toponymie[9] and appears in the current Constitution of the French Republic in articles 72-3 and 73.

History

The island has been inhabited since the 17th century, when people from France and Madagascar settled there. Slavery was abolished on 20 December 1848 (a date celebrated yearly on the island), when the Second Republic abolished slavery in the French colonies. However, indentured workers continued to be brought to Réunion from South India, among other places. The island became an overseas department of France in 1946.

Early history

Not much is known of La Réunion's history prior to the arrival of the Portuguese in the early 16th century.[10] Arab traders were familiar with it by the name Dina Morgabin, "Western Island" (likely Arabic: دنية/دبية مغربي Daniyah/Dībah Maghribīy).[11][dubious – discuss] The island is possibly featured on a map from 1153 AD by Al Sharif el-Edrisi.[citation needed] The island might also have been visited by Swahili or Austronesian (ancient Indonesian–Malaysian) sailors on their journey to the west from the Malay Archipelago to Madagascar.[10]

The first European discovery of the area was made around 1507 by Portuguese explorer Diogo Fernandes Pereira, but the specifics are unclear. The uninhabited island might have been first sighted by the expedition led by Dom Pedro Mascarenhas, who gave his name to the island group around Réunion, the Mascarenes.[12] Réunion itself was dubbed Santa Apolónia after a favourite saint,[11] which suggests that the date of the Portuguese discovery could have been 9 February, her feast day. Diogo Lopes de Sequeira is said to have landed on the islands of Réunion and Rodrigues in 1509.[citation needed]

Isle Bourbon (1642–1793)

By the early 1600s, nominal Portuguese rule had left Santa Apolónia virtually untouched.[12] The island was then occupied by France and administered from Port Louis, Mauritius. Although the first French claims date from 1638, when François Cauche and Salomon Goubert visited in June 1638,[13] the island was officially claimed by Jacques Pronis of France in 1642, when he deported a dozen French mutineers to the island from Madagascar. The convicts were returned to France several years later, and in 1649, the island was named Isle Bourbon after the House of Bourbon. Colonisation started in 1665, when the French East India Company sent the first settlers.[12]

The French colonists developed a plantation economy founded on the cultivation of coffee and sugar by use of slave labor. From the 17th to the 19th centuries, French colonisation, supplemented by importing Africans, Chinese and Indians as workers, contributed to ethnic diversity in the population. From 1690, most of the non-Europeans on the island were enslaved. Of the 80,000 slaves imported to Réunion and Mauritius between 1769 and 1793, 45% was provided by slave traders of the Sakalava people in North West Madagascar, who raided East Africa and the Comoros for slaves, and the rest was provided by Arab slave traders who bought slaves from Portuguese Mozambique and transported them to Réunion via Madagascar.[14]

French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1793–1814)

On 19 March 1793, during the French Revolution, the island's name was changed to "La Réunion" in homage to the meeting of the Federates of Marseille and the National Guards of Paris, during the march on the Tuileries Palace on 10 August 1792, and to erase the name of the Bourbon dynasty.[15]

The abolition of slavery voted by the National Convention on 4 February 1794, was rejected by authorities in Réunion, as well as in Isle de France. A delegation accompanied by military forces, charged with imposing the liberation of slaves, arrived on the island of Bourbon on 18 June 1796, only to be immediately expelled without mercy. There followed a period of unrest and challenges to the power of the metropolis, which no longer had any authority over the two islands. The First Consul of the Republic, Napoleon Bonaparte, maintained slavery there, which was never abolished in practice, with the law of 20 May 1802. On 26 September 1806, the island was renamed Isle Bonaparte and found itself in the front line of the Anglo-French conflict for the control of the Indian Ocean.

Following climatic catastrophes of 1806-1807 (cyclones, floods), coffee cultivation declined rapidly and was replaced by sugar cane, whose demand in France increased, due to France's recent loss of Saint-Domingue, and soon of Isle de France. Because of its growth cycle, sugarcane is not affected by cyclones.

During the Napoleonic Wars, the island was invaded by British forces and its governor, General Sainte-Suzanne, was forced to capitulate on 9 July 1810. The island then came under British rule and was under British occupation until the end of the Napoleonic period. The old name of Isle Bourbon was restored in 1810.

Colony of Bourbon, then Réunion (1814–1946)

Bourbon Island was returned to the French under the Treaty of Paris of 1814. The slave trade openly operated in the colony after French rule was restored, and despite international condemnation Bourbon Island imported 2,000 slaves every month during the 1820s, mostly from the Swahili coast or Quelimane in Portuguese Mozambique.[14] In 1841, Edmond Albius' discovery of hand-pollination of vanilla flowers enabled the island to soon become the world's leading vanilla producer. The cultivation of geranium, whose essence is widely used in perfumery, also took off. From 1838 to 1841, Rear-Admiral Anne Chrétien Louis de Hell was governor of the island. A profound change of society and mentality linked to the events of the last ten years led the governor to present three emancipation projects to the Colonial Council.

On 9 June 1848, after the arrival of news of the French Revolution of 1848 from Europe, governor Joseph Graëb announced the proclamation of the French Republic in Saint-Denis, and on that same day the island was definitely renamed "Réunion", the name it had already held between 1793 and 1806. The establishment of the Republic was met with coldness and distrust by the white plantocracy due to the professed abolitionism of the new Republican authorities in Paris. On 18 October 1848, the new Commissioner of the Republic Joseph Napoléon Sébastien Sarda Garriga, sent from Paris to replace Graëb, announced in Saint-Denis the abolition of slavery in Réunion, effective on 20 December 1848 (December 20 has been an official holiday in Réunion since then). Louis Henri Hubert Delisle became its first Creole governor on 8 August 1852, and remained in this position until 8 January 1858.

After abolition, many foreign workers came as indentured workers. Slavery was replaced by a system of contract labor known as engagés, which lasted from 1848 until 1864.[16] In practice, an illegal slave trade was conducted in which slaves were acquired from Portuguese Mozambique and Zanzibar and then trafficked to Réunion via the Comoros slave trade. They were officially called engagés to avoid the anti-slavery British blockade of Africa.[16]

The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 reduced the importance of the island as a stopover on the East Indies trade route [17] and caused a shift in commercial traffic away from the island. Europe increasingly turned to sugar beet to meet its sugar needs. Despite the development policy of the local authorities and the recourse to compromise, the economic crisis became evident from the 1870s onwards. However, this economic depression did not prevent the modernization of the island, with the development of the road network, the creation of the railroad and the construction of the artificial harbor of the Pointe des Galets. These major construction projects offered a welcome alternative for agricultural workers.

During World War II, Réunion was under the control of Vichy France until 30 November 1942, when Free French forces disembarked from the destroyer Léopard and liberated the colony.[18]

Modern history (since 1946)

La Réunion became a département d'outre-mer (overseas département) of France on 19 March 1946. INSEE assigned to Réunion the department code 974, and the region code 04 when regional councils were created in 1982 in France, including in existing overseas departments which also became overseas regions.

Over about two decades in the late 20th century (1963–1982), 1,630 children from La Réunion were relocated to rural areas of metropolitan France, particularly to Creuse, ostensibly for education and work opportunities. That program was led by influential Gaullist politician Michel Debré, who was an MP for La Réunion at the time.[19] Many of these children were abused or disadvantaged by the families with whom they were placed. Known as the Children of Creuse, they and their fate came to light in 2002 when one of them, Jean-Jacques Martial, filed suit against the French state for kidnapping and deportation of a minor.[20] Other similar lawsuits were filed over the following years, but all were dismissed by French courts and finally by the European Court of Human Rights in 2011.[21]

In 2005 and 2006, La Réunion was hit by a crippling epidemic of chikungunya, a disease spread by mosquitoes. According to the BBC News, 255,000 people on La Réunion had contracted the disease as of 26 April 2006.[22] The neighbouring islands of Mauritius and Madagascar also suffered epidemics of this disease during the same year.[23][24] A few cases also appeared in mainland France, carried by people travelling by airline. The French government of Dominique de Villepin sent an emergency aid package worth €36 million and deployed about 500 troops in an effort to eradicate mosquitoes on the island.[citation needed]

Politics

La Réunion sends seven deputies to the French National Assembly and three senators to the Senate.

Status

Réunion is an overseas department and region of France (known in French as a département et région d'outre-mer, DROM) governed by article 73 of the Constitution of France, under which the laws and regulations are applicable as of right, as in metropolitan France.[25]

Thus, Réunion has a regional council and a departmental council. These territorial entities have the same general powers as the departments and regions of metropolitan France, albeit with some adaptations. Article 73 of the constitution provides for the possibility of replacing the region and the department by a single territorial entity, but, unlike French Guiana or Martinique, there are currently no plans to do so. Unlike the other DROMs, the constitution explicitly excludes Réunion from the possibility of receiving authorization from Parliament to set certain rules itself, either by law or by the national executive.[25] The state is represented in Réunion by a prefect. The territory is divided into four districts (Saint-Benoît, Saint-Denis, Saint-Paul and Saint-Pierre). Réunion has 24 municipalities organized into 5 agglomeration communities. From the point of view of the European Union, Réunion is considered an "outermost region".

Geopolitics

The positioning of La Réunion Island has given it a more or less important strategic role depending on the period.

Already at the time of the India Route or Route des Indes, Réunion was a French possession located between Cape Town and the Indian trading posts, although far from the Mozambique Channel. Isle Bourbon (its name under the Ancien Régime) was not, however, the preferred position for trade and military. Governor Labourdonnais claimed that Isle de France was a land of opportunity, thanks to its topography and the presence of two natural harbours. He intended Isle Bourbon to be a depot or an emergency base for Isle de France.[26]

The opening of the Suez Canal diverted much of the maritime traffic from the southern Indian Ocean and reduced the strategic importance of the island. This decline is confirmed by the importance given to Madagascar, which was later colonized.[17]

Today, the island, the seat of a defense and security zone, is the headquarters of the French Armed Forces of the Southern Indian Ocean Zone (FAZSOI), which brings together French Army units stationed in La Réunion and Mayotte. Réunion is also a base for the so-called Frenchelon signal intelligence system, whose infrastructure includes a mobile listening and automatic search unit. Saint-Pierre is also the headquarters of the mostly uninhabited French Southern and Antarctic Lands (Terres australes et antarctiques françaises, TAAF). Because of France's possession of Réunion, France is a member of the Indian Ocean Commission, which also includes the Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius and the Seychelles.

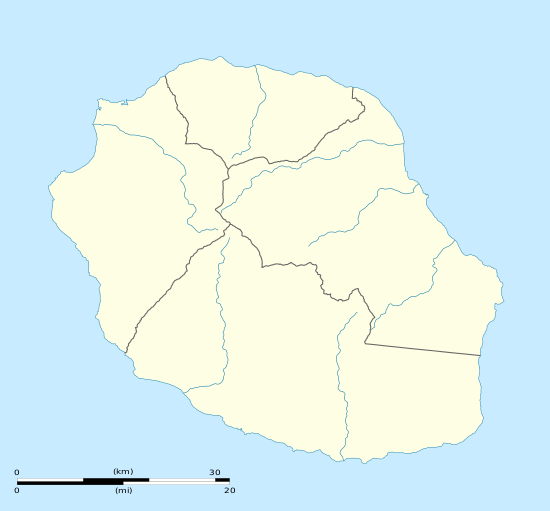

Administrative divisions

Administratively, La Réunion is divided into 24 communes (municipalities) grouped into four arrondissements.[27] It is also subdivided into 25 cantons, meaningful only for electoral purposes at the departmental or regional level. It is a French overseas department, hence a French overseas region. The low number of communes, compared with French metropolitan departments of similar size and population, is unique: most of its communes encompass several localities, sometimes separated by significant distances.

Municipalities (communes)

| Name | Area (km2) | Population (2019)[28] | Coat of arms | Arrondissement | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Les Avirons | 26.27 | 11,440 | Saint-Pierre | ||

| Bras-Panon | 88.55 | 13,057 | Saint-Benoît | ||

| Cilaos | 84.4 | 5,538 | Saint-Pierre | ||

| Entre-Deux | 66.83 | 6,927 | Saint-Pierre | ||

| L'Étang-Salé | 38.65 | 14,059 | Saint-Pierre | ||

| Petite-Île | 33.93 | 12,395 | Saint-Pierre | ||

| La Plaine-des-Palmistes | 83.19 | 6,626 | Saint-Benoît | ||

| Le Port | 16.62 | 32,977 | Saint-Paul | ||

| La Possession | 118.35 | 32,985 | Saint-Paul | ||

| Saint-André | 53.07 | 56,902 | Saint-Benoît | ||

| Saint-Benoît | 229.61 | 37,036 | Saint-Benoît | ||

| Saint-Denis | 142.79 | 153,810 | Saint-Denis | ||

| Saint-Joseph | 178.5 | 37,918 | Saint-Pierre | ||

| Saint-Leu | 118.37 | 34,586 | Saint-Paul | ||

| Saint-Louis | 98.9 | 53,120 | Saint-Pierre | ||

| Saint-Paul | 241.28 | 103,208 | Saint-Paul | ||

| Saint-Philippe | 153.94 | 5,198 | Saint-Pierre | ||

| Saint-Pierre | 95.99 | 84,982 | Saint-Pierre | ||

| Sainte-Marie | 87.21 | 34,061 | Saint-Denis | ||

| Sainte-Rose | 177.6 | 6,345 | Saint-Benoît | ||

| Sainte-Suzanne | 58.84 | 24,065 | Saint-Denis | ||

| Salazie | 103.82 | 7,136 | Saint-Benoît | ||

| Le Tampon | 165.43 | 79,824 | Saint-Pierre | ||

| Les Trois-Bassins | 42.58 | 7,015 | Saint-Paul |

The communes voluntarily grouped themselves into five groups for cooperating in some domains, apart from the four arrondissements to which they belong for purposes of national laws and executive regulation. After some changes in their composition, name and status, all of them operate with the status of agglomeration communities, and apply their own local taxation (in addition to national, regional, departmental, and municipal taxes) and have an autonomous budget decided by the assembly representing all member communes. This budget is also partly funded by the state, the region, the department, and the European Union for some development and investment programs. Every commune in Réunion is now a member of such an intercommunality, with its own taxation, to which member communes have delegated their authority in various areas.

Foreign relations

Although diplomacy, military, and French government matters are handled by Paris, La Réunion is a member of La Francophonie, the Indian Ocean Commission, the International Trade Union Confederation, the Universal Postal Union, the Port Management Association of Eastern and Southern Africa, and the World Federation of Trade Unions in its own right.

Defence

The French Armed Forces are responsible for the defence of the department. These forces also contribute to the defence of other French territories in the region, including Mayotte and the French Southern and Antarctic Lands. A total of some 2,000 French troops are deployed in the region, mostly in La Réunion centred on the 2nd Marine Infantry Parachute Regiment. Two CASA CN 235 aircraft, forming air detachment 181 and drawn from the 50th Air Transport squadron, provide a modest air transport and surveillance capability.[29][30] In 2022, the French Air Force demonstrated a capacity to reinforce the territory by deploying two Rafale fighter aircraft, supported by an A330 MRTT Phénix tanker, from France to Réunion for a regional exercise.[31]

The French naval presence includes two Floréal-class frigates, Floréal and Nivôse, the icebreaker L'Astrolabe, the patrol and support ship Champlain and the coast guard vessel Le Malin. The naval aviation element includes a Eurocopter AS565 Panther helicopter from Flottille 36F able to embark on the Floréal-class frigates as required.[32][29] In 2025, the helicopter is to be replaced by a AS 365N Dauphin.[33] By 2025, Le Malin is to be replaced by Auguste Techer, a vessel of the new Félix Éboué class of patrol vessels.[34] The French Navy will further reinforce its offshore patrol capabilities in the region by deploying a second vessel of the class (Félix Éboué) to Réunion by 2026.[35][36]

About 800 National Gendarmerie, including one mobile squadron and one high mountain platoon, are also stationed in Réunion.[37] The Maritime Gendarmerie has also operated the patrol boat Verdon in the territory[38] (though she was reported forward deployed in Mayotte as of 2022).[39]

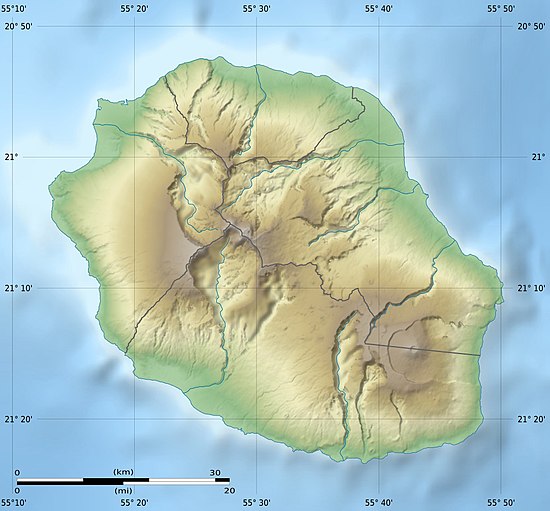

Geography

The island is 63 km (39 mi) long; 45 km (28 mi) wide; and covers 2,512 km2 (970 sq mi). It is above a hotspot in the Earth's crust. The Piton de la Fournaise, a shield volcano on the eastern end of La Réunion, rises more than 2,631 m (8,632 ft) above sea level and is sometimes called a sister to Hawaiian volcanoes because of the similarity of climate and volcanic nature. It has erupted more than 100 times since 1640, and is under constant monitoring, most recently erupting on 2 July 2023.[40] During another eruption in April 2007, the lava flow was estimated at 3,000,000 m3 (3,900,000 cu yd) per day.[41] The hotspot that fuels Piton de la Fournaise also created the islands of Mauritius and Rodrigues.

The Piton des Neiges volcano, the highest point on the island at 3,070 m (10,070 ft) above sea level, is northwest of the Piton de la Fournaise. Collapsed calderas and canyons are south west of the mountain. While the Piton de la Fournaise is one of Earth's most active volcanoes, the Piton des Neiges is dormant. Its name is French for "peak of snows", but snowfall on the summit of the mountain is rare. The slopes of both volcanoes are heavily forested. Cultivated land and cities like the capital city of Saint-Denis are concentrated on the surrounding coastal lowlands. Offshore, part of the west coast is characterised by a coral reef system. Réunion also has three calderas: the Cirque de Salazie, the Cirque de Cilaos and the Cirque de Mafate. The last is accessible only on foot or by helicopter.

- Cirque de Mafate is a caldera formed from the collapse of the large shield volcano the Piton des Neiges.

- Réunion from space (NASA image): The three cirques, forming a kind of three-leafed clover shape, are visible in the central north west of the image. Piton de la Fournaise is in the south east.

- Lava flow emitted in 2005 by the Piton de la Fournaise

- "Plage de l'Ermitage" beach

Geology and relief

La Réunion is a volcanic island born some three million years ago[42] with the emergence of the Piton des Neiges volcano. It has an altitude of 3,070.5 m (10,074 ft), the highest peak in the Mascarene Islands and the Indian Ocean. The eastern part of the island is constituted by the Piton de la Fournaise, a much more recent volcano (500,000 years old) which is considered one of the most active on the planet. The emerged part of the island represents only a small percentage (about 3%) of the underwater mountain that forms it.

In addition to volcanism, the relief of the island is very uneven due to active erosion. The center shelters three vast cirques dug by erosion (Salazie, Mafate and Cilaos) and the slopes of the island are furrowed by numerous rivers digging gullies, estimated at least 600,[43] generally deep and whose torrents cut the sides of the mountains up to several hundreds of meters deep.

The ancient massif of the Piton des Neiges is separated from the massif of La Fournaise by a gap formed by the plaine des Palmistes and the plaine des Cafres, a passageway between the east and the south of the island. Apart from the plains, the coastal areas are generally the flattest regions, especially in the north and west of the island. The coastline of the wild south is however steeper.

Between the coastal fringe and the Hauts, there is a steep transitional zone whose gradient varies considerably before arriving at the ridge lines setting the cirques or the Enclos, the caldera of the Piton de la Fournaise.

Climate

La Réunion is characterized by a humid tropical climate, tempered by the oceanic influence of the trade winds blowing from east to west. The climate of Réunion is characterized by its great variability, mainly due to the imposing relief of the island, which is at the origin of numerous microclimates.

As a result, there are strong disparities in rainfall between the windward coast in the east and the leeward coast in the west, and in temperature between the warmer coastal areas and the relatively cooler highland areas.

In La Réunion there are two distinct seasons, defined by the rainfall regime:

- a rainy season from January to March, during which most of the year's rain falls;

- a dry season from May to November. However, in the eastern part and in the foothills of the volcano, rainfall can be significant even in the dry season;

April and December are transition months, sometimes very rainy but also very dry.

Pointe des Trois Bassins, located on the coast of the commune of Trois-Bassins (west), is the driest season, with a normal annual precipitation of 447.7 mm (17.63 in), while Le Baril, in Saint-Philippe (southeast), is the wettest coastal season, with a normal annual precipitation of 4,256.2 mm (167.57 in).[44]

However, the wettest station is in the highlands of Sainte-Rose, with an average annual rainfall of almost 11,000 mm (430 in), making it one of the wettest places in the world.

Temperatures in La Réunion are characterized by their great mildness throughout the year. In fact, the thermal amplitude from one season to another is relatively small (rarely exceeding 10 °C or 18 °F), although it is perceptible:

- In the warm season (November to April): average minimums usually range between 21 and 24 °C (70 and 75 °F), and average maximums between 28 and 31 °C (82 and 88 °F), on the coast. At 1,000 m (3,300 ft), average minimums fluctuate between 10 and 14 °C (50 and 57 °F) and average maximums between 21 and 24 °C (70 and 75 °F);

- In the cold season (May to October): temperatures at sea level vary from 17 to 20 °C (63 to 68 °F) for average minimums and from 26 to 28 °C (79 to 82 °F) for average maximums. At 1,000 m (3,300 ft), average minimums range from 8 to 10 °C (46 to 50 °F) and average maximums from 17 to 21 °C (63 to 70 °F).

In mountain towns, such as Cilaos or La Plaine-des-Palmistes, average temperatures range between 12 and 22 °C (54 and 72 °F). The highest parts of the habitat and the natural areas at altitude may suffer some winter frosts. Snow was even observed on the Piton des Neiges and Piton de la Fournaise in 2003 and 2006.[45]

The warmest day on record was set on 30 January 2022. In the cold pole of the La Réunion (all-time low −5 °C or 23 °F) Gite de Bellecombe (2,245 m or 7,365 ft AMSL) with a maximum temperature of 25.4 °C (77.7 °F). It beats the previous record of 25.1 °C (77.2 °F) set in 2021.

While a growing number of islands (including "non-sovereign" islands) in the world are concerned about the effects of climate change, the island of Réunion was chosen (along with Gran Canaria in Spain) as an example for a case study of an affected ultra-European peripheral territory, for a study on the adequacy of urban and regional planning tools to the needs and characteristics of these islands (including land use and population density and the regulatory framework).

This work confirmed that urban and peri-urban land use pressures are high, and that adaptation strategies are incompletely integrated into land use planning. According to the Institute of Island Studies, there is a dysfunction: "island planning tools often do not take climate change adaptation into account and there is too much top-down management in the decision-making process".[46] Réunion holds the world records for the most rainfall in 12-, 24-, 72- and 96-hour periods,[47] including 1.8 metres (5 ft 11 in) in 24 hours.[48]

Beaches

La Réunion hosts many beaches. They are often equipped with barbecues, amenities, and parking spaces. Hermitage Beach is the most extensive and best-preserved lagoon in Réunion Island and a popular snorkelling location.[49] It is a white sand beach lined with casuarina trees under which the locals often organise picnics.

At La Plage des Brisants, a surfing spot, many athletic and leisure activities take place. Each November, a film festival is organised there. Movies are projected on a large screen in front of a crowd.

Beaches at Boucan Canot are surrounded by a stretch of restaurants that particularly cater to tourists. L'Étang-Salé on the west coast is covered in black sand consisting of tiny fragments of basalt. This occurs when lava contacts water, it cools rapidly and shatters into the sand and fragmented debris of various size. Much of the debris is small enough to be considered sand. Grand Anse is a tropical white-sand beach lined with coconut trees in the south of Réunion, with a rock pool built for swimmers, a pétanque playground, and a picnic area. Le Vieux Port in Saint Philippe is a green-sand beach consisting of tiny olivine crystals, formed by the 2007 lava flow, making it one of the youngest beaches on Earth.[50]

- Sunset at Grand Anse beach Réunion Island

- Manapany beach rock pool

- L'Étang-Salé Beach - a black sand beach from volcanic basalt

- L'Ermitage les Bains lagoon in front of Saint Paul, and its pass through the coral reef

Environment

Flora

The tropical and insular flora of La Réunion Island is characterized by its diversity, a very high rate of endemism and a very specific structure. The flora of La Réunion presents a great diversity of natural environments and species (up to 40 tree species/ha, compared to a temperate forest which has an average of 5/ha). This diversity is even more remarkable, but fragile, as it differs according to the environment (coastal, low, medium and high mountain).

La Réunion has a very high rate of endemic species, with more than 850 native plants (of natural origin and present before the arrival of humans), of which 232 are endemic to the La Réunion (only present on the island), as well as numerous species endemic to the Mascarene archipelago. Finally, the flora of La Réunion is distinguished from that of equatorial tropical forests by the low height and density of the canopy, probably due to adaptation to cyclones, and by a very specific vegetation, in particular a strong presence of epiphytic plants (growing on other plants), such as orchids, bromeliads[citation needed] and cacti[citation needed], but also ferns, lichens and mosses.[51]

Wildlife

Like its prodigious floral diversity, Réunion is home to a variety of birds such as the white-tailed tropicbird (French: paille en queue).[52] Many of these birds species are endemic to the island, such as the Réunion harrier and Réunion cuckooshrike. Its largest land animal is the panther chameleon, Furcifer pardalis. Much of the west coast is ringed by coral reef which harbours, among other animals, sea urchins, conger eels, and parrot fish. Sea turtles and dolphins also inhabit the coastal waters. Humpback whales migrate north to the island from the Antarctic waters annually during the Southern Hemisphere winter (June–September) to breed and feed, and can be routinely observed from the shores of Réunion during this season.

Beekeepers began importing European honey bees during the late 19th century, which in turn have breed with the endemic Apis mellifera unicolor subspecies which originated from Madagascar. 97% of the honey bees on the island are descended from A. m. unicolor, however their DNA only accounts for 53% of the genetic mixture. In an attempt to prevent the spread of diseases a bee importation ban was imposed in 1982,[53] however in 2017 one or two Varroa destructor mites were brought into the island when a Queen bee was smuggled in by a beekeeper, within 4.5 months the mites had spread throughout the island, causing an increase of annual deaths of colonies from 0.6% to 64%,[54] after initially reaching 85%.[55][56]

At least 19 species formerly endemic to Réunion have become extinct following human colonisation. For example, the Réunion giant tortoise became extinct after being slaughtered in vast numbers by sailors and settlers of the island.

- A juvenile Emperor angelfish

- A white-tailed Tropicbird

- A Humpback whale off St-Gilles

Marine biodiversity

Despite the small area of coral reefs, the marine biodiversity of La Réunion is comparable to that of other islands in the area, which has earned the Mascarene archipelago its inclusion among the top ten global biodiversity "hotspots".[57] Réunion's coral reefs, both flat and barrier, are dominated mainly by fast-growing branching coral species of the genus Acropora (family Acroporidae), which provide shelter and food for many tropical species.

Recent scientific research in Réunion Island indicates that there are more than 190 species of corals, more than 1,300 species of mollusks, more than 500 species of crustaceans,[58] more than 130 species of echinoderms and more than 1,000 species of fish.[59]

La Réunion's deeper waters are home to dolphins, killer whales, humpback whales, blue sharks and a variety of shark species, including whale sharks, coral sharks, bull sharks, tiger sharks, blacktip sharks and great white sharks. Several species of sea turtles live and breed here.

Between 2010 and 2017, 23 shark attacks occurred in the waters of La Réunion, of which nine were fatal.[60] In July 2013, the Prefect of Réunion Michel Lalande announced a ban on swimming, surfing, and bodyboarding off more than half of the coast. Lalande also said 45 bull sharks and 45 tiger sharks would be culled, in addition to the 20 already killed as part of scientific research into the illness ciguatera.[61]

Migrations of humpback whales contributed to a boom of whale watching industries on Réunion, and watching rules have been governed by the OMAR (Observatoire Marin de la Réunion) and Globice (Groupe local d'observation et d'identification des cétacés).

Coral reef

Because the island is relatively young (3 million years old),[42] the coral formations (8,000 years old) are not well developed and occupy a small area compared to older islands, mostly in the form of fringing reefs.[42]

These formations define shallow "lagoons" (rather "reef depressions"), the largest of which is no more than 200 m (660 ft) wide and about 1–2 m (3.3–6.6 ft) deep.[62] These lagoons, which form a discontinuous reef belt 25 km (16 mi) long (i.e. 12% of the island's coastline) with a total area of 12 km2 (4.6 sq mi), are located on the west and southwest coast of the island. The most important are those of L'Ermitage (St-Gilles), St-Leu, L'Étang-Salé and St-Pierre.

Management

Since 2010, La Réunion is home to a UNESCO World Heritage Site that covers about 40% of the island's area and coincides with the central zone of the La Réunion National Park.[63] The island is part of the Mascarene forests terrestrial ecoregion.[64]

Gardening and Bourbon roses

The first members of the "Bourbon" group of garden roses originated on this island (then still Isle Bourbon, hence the name) from a spontaneous hybridisation between Damask roses and Rosa chinensis,[65] which had been brought there by the colonists. The first Bourbon roses were discovered on the island in 1817.[66]

Threats to the environment

Among coastal ecosystems, coral reefs are among the richest in biodiversity, but they are also the most fragile.[67]

Nearly one-third of fish species were already considered threatened or vulnerable in 2009, with coral degradation in many places. The causes of this state of affairs are pollution, overfishing and poaching, as well as anthropogenic pressure, especially linked to the densification of urbanization in coastal areas and the discharge of sewage.[68]

15 species living on La Réunion were included in the Red List published by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).[69]

Demographics

Historical population

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Local population estimates and censuses up to 1946.[70][71] INSEE censuses between 1954 and 2021.[72][1] Last INSEE 2024 estimate.[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Major metropolitan areas

The most populous metropolitan area is Saint-Denis, which covers six communes (Saint-Denis, Sainte-Marie, La Possession, Sainte-Suzanne, Saint-André, and Bras-Panon) in the north of the island.[73] The three largest metropolitan areas are:[74]

| Urban unit | Population (2021) |

|---|---|

| Saint-Denis | 319,141 |

| Saint-Pierre-Le Tampon | 224,549 |

| Saint-Paul | 172,302 |

Migration and ethnic groups

At the 2019 census, 82.4% of the inhabitants of La Réunion were born on the island, 11.7% were born in Metropolitan France, 1.0% were born in Mayotte, 0.3% were born in the rest of Overseas France, and 4.6% were born in foreign countries (46% of them children of French expatriates and settlers born in foreign countries, such as children of Réunionese settlers born in Madagascar during colonial times; the other 54% immigrants, i.e. people born in foreign countries with no French nationality at birth).[75]

In recent decades, the number of Metropolitan Frenchmen living on the La Réunion has increased markedly: only 5,664 natives of Metropolitan France lived in Réunion at the 1967 census, but their numbers were multiplied by more than six in 23 years, reaching 37,516 at the 1990 census, and then nearly tripled in the next three decades, reaching 100,493 at the 2019 census.[76][77][75] Native Réunionese, meanwhile, have emigrated increasingly to Metropolitan France: the number of natives of La Réunion living in Metropolitan France rose from 16,548 at the 1968 census to 92,354 at the 1990 census to 130,662 at the 2019 census, by which date 15.7% of the natives of Réunion lived outside of the department.[77][75]

La Réunion has received little immigration since World War II, and by the 2019 census only 2.5% of its inhabitants were immigrants. This is in contrast to the situation that prevailed from the middle of the 19th century until World War Two when many migrants from India (especially from Tamil Nadu and Gujarat),[78] Eastern Asia (particularly China), and Africa came to La Réunion to work in the plantation economy. Their descendants have now become French citizens.

| Census | Born in Réunion | Born in Metropolitan France | Born in Mayotte | Born in the rest of Overseas France | Born in foreign countries with French citizenship at birth1 | Immigrants2 |

| 2019 | 82.4% | 11.7% | 1.0% | 0.3% | 2.1% | 2.5% |

| 2013 | 83.7% | 11.1% | 0.7% | 0.3% | 2.2% | 2.0% |

| 2008 | 84.6% | 10.3% | 0.8% | 0.2% | 2.4% | 1.8% |

| 1999 | 86.1% | 9.1% | 0.9% | 0.4% | 2.0% | 1.4% |

| 1990 | 90.4% | 6.3% | 0.2% | 0.1% | 1.9% | 1.0% |

| 1982 | 93.1% | 4.1% | 2.8% | |||

| 1967 | 96.8% | 1.4% | 1.8% | |||

| ||||||

| Source: IRD,[76] INSEE[77][75] | ||||||

Ethnic groups present include people of African, Indian, European, Malagasy and Chinese origin. Local names for these are Yabs, Cafres, Malbars and Chinois. All of the ethnic groups on the island are immigrant populations that have come to Réunion from Europe, Asia and Africa over the centuries. These populations have mixed from the earliest days of the island's colonial history (the first settlers married women from Madagascar and of Indo-Portuguese heritage), resulting in a majority population of mixed race and of "Creole" culture.

It is not known exactly how many people of each ethnicity live in La Réunion, since the French census does not ask questions about ethnic origin,[79] which applies in La Réunion because it is a part of France in accordance with the 1958 constitution. The extent of racial mixing on the island also makes ethnic estimates difficult. According to estimates, Whites make up roughly one quarter of the population,[80] Malbars make up more than 25% of the population and people of Chinese ancestry form roughly 3%.[81] The percentages for those of African and mixed-race origins vary widely in estimates. Also, some people of Vietnamese ancestry live on the island, though they are very few in number.[82][83][84]

Tamils are the largest group among the Indian community.[85] The island's community of Muslims from northwestern India, particularly Gujarat, and elsewhere is commonly referred to as zarabes.

Creoles (a name given to those born on the island, regardless of ethnic origins) make up the majority of the population. Groups that are not Creole include people recently arrived from Metropolitan France (known as zoreilles) and those from Mayotte and the Comoros as well as immigrants from Madagascar and Sri Lankan Tamil refugees.

Religion

Religious affiliation (2000 censuses)[86]

The predominant religion is Christianity. The Catholic Church has a single jurisdiction, the Diocese of Saint-Denis-de-La Réunion. Religious Intelligence estimates Christians to be 84.9% of the population, followed by Hindus (10%) and Muslims (2.15%).[84] Chinese folk religion and Buddhism are also represented.

Most large towns have a Hindu temple and a mosque.[87]

Ritual

See also: Kabaré (fête) §Les sèrvis kabaré (in French)

There are traditional Réunionnais ceremonial practices (Les sèrvis kabaré, Servis kaf or Servis zansèt) of ancestor veneration arising from Malagasy roots, blended with Malabar, Comorian, European, and Chinese cultural influences. These may be practiced by those adhering to the main religions of Christianity, Hinduism and Islam.[88]

Culture

Réunionese culture is a blend (métissage) of European, African, Indian, Chinese and insular traditions. The most widely spoken language, Réunion Creole, derives from French.

Language

French is the sole official language of Réunion. Though not official, Réunion Creole is widely spoken alongside French. Creole is commonly used for informal purposes, whereas the official language for administrative purposes, as well as education, is French.[89]

Other languages spoken on La Réunion include: Comorian varieties (especially Shimaore) and Malagasy, by recent immigrants from Mayotte and Madagascar; Mandarin, Hakka and Cantonese by members of the Chinese community; Indian languages, mostly Tamil, Gujarati and Hindi; and Arabic, spoken by a small community of Muslims. These languages are generally spoken by immigrants, as those born on the island tend to use French and Creole.

Cantonese, Arabic and Tamil are offered as optional languages in some schools.[85]

Music and dance

Two forms make up the musical tradition of Réunion Island. One, the sega, is a Creole variant of the quadrille, the other, the maloya, like the American blues, comes from Africa, carried by the nostalgia and pain of enslaved people uprooted and deported from their homeland. Sega is present on other islands, while maloya is traditional only in Réunion.

The sega is a disguised ballroom dance to the rhythm of traditional Western instruments (accordion, harmonica, guitar, etc.), and stems from the wider colonial society at the time. It is still the typical ballroom dance of the islands of Réunion, Rodrigues, Seychelles, and the Mascarene archipelago in general. Mauritian sega and Rhodesian sega also continue.

The slaves' maloya, a ritual dance full of melodies and gestures, was performed, often clandestinely, at night around a bonfire; the few instruments that accompanied it were made of plants (bamboo, gourds, etc.). Performance was often an underground activity on plantations as slaveholders disapproved of this cultural expression by the enslaved. From the 1960s, it was suppressed by the French government who feared its association with Réunionnais pro-autonomy movements and with communism.[90] The sometimes controversial lyrics reminded France of its slave-owning past and underlined the damage this colonial era did to human beings; in the course of the island's history, Maloya artists and kabar (French: kabaré; gatherings) were banned by authorities. Maloya troupes continued to perform in the face of official repression: along with their artistic expression, they wanted to perpetuate the memory of the slaves, their suffering and their uprooting. The French government's attitude to Maloya did not alter until 1981, when François Mitterrand became president.[90][91]

Every 20 December, the inhabitants of La Réunion celebrate Réunion Freedom Day. This celebration, also known as the Fête des Cafres (or in Réunion Creole French: Fet' Kaf, also, 20 desamb), commemorates the proclamation of the final abolition of slavery by governor Joseph Sarda for the French Second Republic in 1848.[92] Numerous concerts are organized, most of them free, as well as costume parades and dance shows such as merengue, for example.

With the institution of a public holiday to celebrate the abolition of slavery, maloya has received official and wider cultural recognition; it is regularly played on public radio and in many discotheques and dance parties. A revival of maloya, beginning in the 1970s and particularly identified with musician Danyèl Waro, a protégé of Firmin Viry, raised its cultural status. Groups began to make modern versions, styles and arrangements, such as maloggae and other electric maloya.[93][94]

Some of Réunion's emblematic maloya artists and groups include: Groupe folklorique de La Réunion; Kalou Pilé; Baster; Ousanousava; Ziskakan; Pat'Jaune; Danyèl Waro; and Tisours. One of the most revered Maloya singers was fr:Lo Rwa Kaf. Born in Sainte-Suzanne, he was one of the first to sing Maloya.[95] When he died in 2004, many people were present at his funeral.

In 2008, the artist and musician Brice Guilbert made a video entitled La Réunion. In this clip, we see him crossing all the landscapes of the island.

In the field of contemporary dance, the choreographer Pascal Montrouge, who directs the only company in France that has a double headquarters in Saint-Denis de La Réunion and Hyères, which reinforces the sense of his vision of identity. In 2007, the city of Saint-Denis de La Réunion entrusted him with the artistic direction of its Saint-Denis Danses festival.

The island is home to the regional conservatory of La Réunion, which has four teaching centres and was created in 1987 under the impetus of the then president of the region, Pierre Lagourgue. Today, although traditional dances are not forgotten in the conservatoires (which teach dance, music and theatre), the dances taught are classical dance, contemporary dance and Bharata natyam dance. These students regularly have the opportunity to dance with choreographers from Réunion such as Didier Boutiana cie "Konpani Soul city", Soraya Thomas cie "Morphose" or Éric Languet cie "Danse en l'R". These different local companies allow the inhabitants of Réunion to dance professionally.

Urban culture has also made its appearance, following the trends and influences of metropolitan France and the United States. Thus, hip-hop culture is developing, but also ragga dancehall, with KM David or Kaf Malbar being the figurehead of this new movement, influencing the young generation all over the island, with their songs spread by mp3 or internet. Many young artists are trying to "break through" in this music, whose industry is developing reasonably well, locally but also internationally, and has nothing to envy from the precursors of French dancehall.

Cuisine

Always accompanied by rice, the most common dishes are carry (sometimes spelled cari), a local version of Indian curry, rougail and civets (stews). Curry is made with a base of onion, garlic and spices such as turmeric (called "safran péi" on the island),[96] on which fish, meat and eggs are fried; tomato is then added. Dishes can also be flavoured with ginger; the peel of a combava is often prized. Chop suey (with rice, not pasta) and other Asian dishes such as pork with pineapple[97]

Some examples of popular réunionese dishes include:

- Achards (inspired by achaar)

- Cabri massalé

- Cari poulet

- Rougail dakatine

- Rougail morue

- Rougail saucisse

- Bouchon

In general, there are few dishes without meat or fish, so there are few vegetarian options. One of them is chouchou chayote gratin. Otherwise, mainly poultry is consumed. One of the local specialties is tangue[98] civet (of the hedgehog family).

Sport

Moringue is a popular combat/dance sport similar to capoeira. There are several famous Réunionese sportsmen and women like the handballer Jackson Richardson, as well as the karateka Lucie Ignace. La Réunion has a number of contributions to worldwide professional surfing. It has been home to notable pro surfers including Jeremy Flores, Johanne Defay and Justine Mauvin. Famous break St Leu has been host to several world surfing championship competitions. Since 1992, Réunion has hosted a number of ultramarathons under the umbrella name of the Grand Raid. As of 2018, four different races compose the Grand Raid: the Diagonale des Fous, The Trail de Bourbon, the Mascareignes, and the Zembrocal Trail.[99] Annual athletics Meeting de la Réunion is held at the Stade Paul Julius Bénard by the governing body Ligue Réunionnaise d'athlétisme.[100]

Football

Football (soccer) is the most popular sport. With more than 30,000 licensed players for a population exceeding 850,000 inhabitants, it remains the sport of choice for young people. Although the highest level of competition called the First Division of Réunion is equivalent to a division d'honneur in metropolitan France (DH), all the youngsters hope to play at the highest level one day.

This has been the case for players such as Laurent Robert, Florent Sinama-Pongolle, Guillaume Hoarau, Dimitri Payet, Benoit Tremoulinas, Melvine Malard (the only six Reunionese to have played for the French national team), Bertrand Robert, Thomas Fontaine, Ludovic Ajorque, Fabrice Abriel (of La Réunion descent) and Wilfried Moimbe (of Réunion descent), to name but a few. The territory has its own team, the Réunion national football team.

Architecture

Structurally, the local Creole house is said to be symmetrical.[101] In fact, in the absence of an architect, workers would draw a line on the ground and build two identical parts on each side, resulting in houses of essentially rectangular shape. The veranda is an important element of the house. It is an outdoor terrace built on the front of the house, as it allowed to show its richness to the street. A Creole garden completes the house. It is composed of local plants, found in the forest. There is usually a greenhouse with orchids, anthuriums and different types of ferns.

The Villa Déramond-Barre is a Creole architectural model of great heritage interest.[102]

Traditions

Media

Broadcasting

Réunion has a local public television channel, Réunion 1ère, which now forms part of France Télévision, and also receives France 2, France 3, France 4, France 5 and France 24 from metropolitan France, as well as France Ô, which shows programming from all of the overseas departments and territories. There are also two local private channels, Télé Kréol and Antenne Réunion.

It has a local public radio station, formerly Radio Réunion, but now known as Réunion 1ère, like its television counterpart. It also receives the Radio France networks France Inter, France Musique and France Culture. The first private local radio station, Radio Freedom, was introduced in 1981. They broadcast daily content about weather and local services.

Newspapers

There were three daily newspapers published locally. In 2024, one closed. Of the remaining two, one is now produced online only. There are other – weekly and monthly – publications in Réunion, including general interest and television magazines.

The dailies:

- Journal de l'île de La Réunion, founded in 1951, it closed in 2024 after being placed into bankruptcy ("judicial liquidation") on July 31.[103]

- Le Quotidien de La Réunion, founded 1976[104]

- Témoignages, founded 1944; online only since 2013[105]

Cinema

Present on the island since 1896, is marked by its insularity and its geographical distance from metropolitan France. In the absence of the Centre national de la cinématographie (CNC), it has developed specific distribution and dissemination networks. Its landscapes first served as a natural backdrop for many film and television productions, and film events, such as festivals, multiplied there. Digital technology now facilitates the development of local productions, most of which reflect the particularities of a multicultural and multilingual society.

The Réunion Film festival (festival du film de La Réunion) was created in 2005 and is chaired by Fabienne Redt. The festival presented first and second feature films by French directors. The 10th and last edition took place in 2014 in partnership mainly with the TEAT Champ Fleuri (Saint-Denis) and the city of Saint-Paul.

In the Port, the International Film Festival of Africa and the La Réunion Islands (Festival international du film d'Afrique et des îles de La Réunion) was also held.

Among the existing film festivals is the Réunion Island Adventure Film Festival (13 editions), which awards prizes to adventure films.

In Saint-Philippe, the Festival Même pas peur, Réunion's international fantasy film festival, has been held since 2010.

In Saint-Pierre, there are two festivals: Écran jeunes (25th edition in 2019) and the Festival du Film Court de Saint-Pierre, directed by Armand Dauphin (3rd edition in 2019).

Film

- Adama (animated there)

- Mississippi Mermaid (1969) (filmed there)

Blogs

- Reunion Island Tourism blog (English/French tourism blog)

- Visit Reunion (English language blog and Instagram page)[106][non-primary source needed]

Internet

The internet situation in Réunion was once marked by its insularity and remoteness from mainland France, which caused some technological delays. Today, the trend has been reversed and the region has a relatively efficient internet connection and is one of the departments most connected by fibre optics in France.

Internet connection can be provided by ADSL (offered by four operators), fibre optic (three operators), or by cellular data on 4G and 5G networks (currently being tested in Saint-Denis).

Réunion domain names have the suffix .re. The La Réunion region has deployed a regional fibre-optic network for operators. This network is based partly on EDF's very high voltage cables - G@zelle network, partly on the region's own fibre and partly on Hertzian links for the most isolated areas. This network is managed by a public service company called La Réunion Numérique.[107]

Economy

In 2019, the GDP of Réunion at market exchange rates, not at PPP, was estimated at 19.5 billion euros (US$21.8 bn) and the GDP per capita (also at market exchange rates) was 22,629 euros (US$25,333),[citation needed] the highest in sub-Saharan Africa,[108] but only 61.7% of metropolitan France's GDP per capita that year, and 73.5% of the metropolitan French regions outside the Paris Region.[109]

Before the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, the economy of La Réunion was in a process of catching up with the rest of France. From 1997 to 2007, the economy of La Réunion grew by an average of +4.6% per year in real terms,[110] and the GDP per capita rose from 53.7% of metropolitan France's level in 2000 to 61.6% of metropolitan France in 2007.[109] The Great Recession that followed the financial crisis greatly affected La Réunion whose economy came to a standstill in 2008, then experienced two years of recession in 2009 and 2010, followed by three years of stagnation (2011-2013).[110] By 2013, the GDP per capita of Réunion had fallen back to 60.6% of metropolitan France's level.[109]

Economic growth returned in 2014. The economy grew by an average of +2.9% per year in real terms from 2014 to 2017, and the GDP per capita of Réunion rose to 62.4% of metropolitan France's GDP per capita by 2017, its highest level ever.[109] The economy slowed down in 2018, growing at only +1.7% due in part to the yellow vests protests which paralyzed the Réunionese economy in the end of 2018, before recovering to +2.2% in 2019.[110] As a result of this slower growth since 2018, the GDP per capita of Réunion fell back slightly compared to metropolitan France's, standing at 61.7% of metropolitan France's level in 2019.[109]

Réunion was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, leading to a massive recession of -4.2% that year according to provisional estimates, the largest on record,[110] although less severe than in metropolitan France (-7.9% for metropolitan France in 2020).[109]

| 2000 | 2007 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal GDP (€ bn) | 9.55 | 15.17 | 16.53 | 16.97 | 17.55 | 18.07 | 18.56 | 19.00 | 19.51 |

| GDP per capita (euros) | 13,218 | 18,937 | 19,701 | 20,045 | 20,608 | 21,171 | 21,707 | 22,128 | 22,629 |

|

53.7% | 61.6% | 60.6% | 61.0% | 61.5% | 62.4% | 62.4% | 62.0% | 61.7% |

| Source: INSEE.[109] | |||||||||

Sugar was traditionally the chief agricultural product and export. Tourism is now an important source of income.[111] The island's remote location combined with its stable political alignment with Europe makes it a key location for satellite receiving stations[112] and naval navigation.[113]

GDP sector composition in 2017 (contribution of each sector to the total gross value added):[114]

| Sector | % of total GVA | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 1.9% | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Mining and quarrying | 0.0% | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Manufacturing | 4.6% | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Utilities | 1.6% | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Construction | 5.8% | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Market services | 49.8% | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Non-market services | 36.2% | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Unemployment is a major problem on Réunion, although the situation has improved markedly since the beginning of the 2000s: the unemployment rate, which stood above 30% from the early 1980s to the early 2000s, declined to 24.6% in 2007, then rebounded to 30.0% in 2011 due to the 2008 global financial crisis and subsequent Great Recession, but declined again after 2011, reaching 19.0% in 2023,[115] its lowest level in 45 years.[116]

In 2021, 36.1% of the population lived below the poverty line (defined by INSEE as 60% of Metropolitan France's median income; in 2021 the poverty line for a family of two parents and two young children was €2,423 (US$2,868) per month),[117] a marked decrease compared to 2013 when 49% of the population lived below the poverty line.[118]

Rum distillation contributes to the island's economy. A "Product of France", it is shipped to Europe for bottling, then shipped to consumers around the world.

Brasseries de Bourbon is the main brewery of the island, with Heineken as shareholder.

Tourism

Income from tourism is La Réunion's primary economic resource, ahead of sugarcane production and processing, which has allowed the development of large Réunionese groups such as Quartier Français, Groupe Bourbon ex-Sucreries Bourbon, a large international company now listed on the stock exchange, but based outside the island and which has abandoned the sugar sector for the off-shore maritime sector. With the reduction of subsidies, this culture is threatened. Therefore, the development of fishing in the French Southern Territories has been promoted.

The tertiary sector, particularly the commercial sector, is by far the most developed, and import distribution has taken off in the mid-1980s through affiliation and franchising agreements with metropolitan groups. The advent of franchised distribution has transformed the commercial apparatus, which historically was characterized by the geographic dispersion of small grocery-type units; the few "Chinese stores" still in operation are limited to mid-range towns and, as relics of a bygone era, have more of a tourist and educational appeal, even if they retain a convenience store function.

Despite its economic dynamism, the island is unable to absorb its significant unemployment, which is explained in particular by a very strong demographic growth. Many Réunioners are forced to move to metropolitan France for their studies or to find work.

Agriculture

Agriculture in Réunion is an important activity in the island's economy:[119] the agricultural territory covering 20% of the island's surface area employs 10% of the active population, generates 5% of the gross regional product and provides the island's main export. Formerly centered on coffee and clove cultivation, it has focused on sugar cane since the events of the early 19th century, namely the Great Avalanches and the seizure of Réunion by the British. Today it faces important issues related to the decisions of the World Trade Organization at the international level and the development of the urban fact at the local level.

Réunion Island has about 7,000 farms, 5,000 of which are professional. These farms mobilize almost 11,000 AWU (annual workload of one person on a full-time basis).

Ninety-seven percent of the farms in Réunion are less than 20 hectares in size, compared to an average of 78 hectares in mainland France.

The most common status is that of individual farmer (97%).

In 2005, more than 60% of farm managers were between 40 and 59 years old.

Public services

Health

In 2005–2006, Réunion experienced an epidemic of chikungunya, a viral disease similar to dengue fever brought in from East Africa, which infected almost a third of the population because of its transmission through mosquitoes. The epidemic has since been eradicated. See the History section for more details.

Transport

Roland Garros Airport serves the island, handling flights to mainland France, Madagascar, Mauritius, Tanzania, Comoros, Seychelles, South Africa, China and Thailand. Pierrefonds Airport, a smaller airport, has some flights to Mauritius and Madagascar. In 2019 a light rail system was proposed to link Le Barachois with the airport.[120]

Education

Réunion Island has its own education system. Chantal Manès-Bonnisseau, Inspector General of Education, Sport and Research, was appointed Rector of the Académie de La Réunion and Chancellor of Universities at the Council of Ministers on 29 July 2020.

She succeeds Vêlayoudom Marimoutou, who took office as secretary general of the Indian Ocean Commission on 16 July.

The Rectorate is located in the main city, in the Moufia district of Saint-Denis. At the start of the 2012 school year, the island had 522 pre-school or primary schools, including 26 private schools, for 120,230 students at the primary level, 82 secondary schools, including six private schools, for 61,300 students, 32 general and technological high schools, including three private schools, for 23,650 students, and 15 vocational schools, including two private schools, for 16,200 students.

Réunion's priority education zones affect slightly more than half of the primary and secondary school students.[121]

Baccalaureate results are relatively close to the national average with a rate of 81.4% in 2012 compared to 82.4% in 2011 (respectively: 84.5% and 85.6% in the national average).

In higher education, the University of La Réunion has 11,600 students spread across the various sites, especially in Saint-Denis and Le Tampon. A further 5,800 students are divided between the post-baccalaureate courses of secondary education and other higher studies.[122]

Energy

Energy on Réunion depends on oil and is limited by the island's insularity, which forces it to produce electricity locally and import fossil fuels. Faced with increasing demand and environmental requirements, the energy produced on the island is tending to increasingly exploit its great renewable energy potential through the development of wind farms, solar farms and other experimental projects. Although 35% of La Réunion's electricity came from renewable sources in 2013, the department's energy dependency rate exceeds 85%. Saving electricity and optimising energy efficiency are two major areas of work for the authorities responsible for energy issues.

Hydroelectric power

Due to the large volumes of rainfall, the flow of surface water allows the installation of hydroelectric infrastructures, especially as erosion has carved out narrow and very deep ravines. The Sainte-Rose plant (22 MW) and the Takamaka plant (17.5 MW) are the two largest. In total, the island's six hydroelectric infrastructures have a capacity of 133 MW.

Symbols

La Réunion has no official coat of arms or flag.

Former Governor Merwart created a coat of arms for the island on the occasion of the 1925 colonial exhibition organised on Petite-Île. Merwart, a member of the Réunion Island Society of Sciences and Arts, wanted to include the island's history:

- the bees evoke the Empire;

- the central coat of arms evokes the French Republican flag;

- the fleurs-de-lis evoke the royal era;

- The motto "Florebo quocumque ferar" is that of the French East India Company and means "I will bloom wherever they take me", while the vanilla vines honour a flourishing harvest.

- The Roman numeral "MMM" evokes the altitude of the highest peaks;

- the ship Saint-Alexis is the one that first took possession of the island;

The most commonly used flag in La Réunion is that of the "radiant volcano", designed by Guy Pignolet in 1975, sometimes called "Lo Mavéli":[123] it represents the volcano of Piton de la Fournaise in the form of a simplified red triangle on a navy blue background, while five sunbeams symbolise the arrival of the populations that have converged on the island over the centuries.[124]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ a b c d "Estimation de population par région, sexe et grande classe d'âge – Années 1975 à 2024" (in French). Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ CEROM (5 October 2024). "Comptes économiques rapides de La Réunion 2023" (in French). Retrieved 12 December 2024.

- ^ Réunion is pictured on all Euro banknotes, on the back at the bottom of each note, right of the Greek ΕΥΡΩ (EURO) next to the denomination.

- ^ "Scoop : Le drapeau réunionnais ne s'appelle pas "lo mavéli" !". guide-reunion.fr (in French). 9 October 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ Jean Baptiste Duvergier, Collection complète des lois [...], éd. A. Guyot et Scribe, Paris, 1834, «Décret du 23 mars 1793», p. 205

- ^ Daniel Vaxellaire, Le Grand Livre de l'histoire de La Réunion, vol. 1 : Des origines à 1848, éd. Orphie, 2000, 701 p. ISBN 978-2-87763-101-3 et 978-2877631013), p. 228 (avec fac-similé du décret).

- ^ Nouveau recueil général de traités, conventions et autres transactions remarquables – Année 1848, éd. Librairie de Dieterich, 1854, «Arrêté du gouvernement provisoire portant changement du nom de l'île Bourbon, Paris, 7 mars», p. 76

- ^ Lexique des règles typographiques en usage à l'Imprimerie nationale, Imprimerie nationale, 1990 ISBN 978-2-11-081075-5 ; réédition 2002 ISBN 978-2-7433-0482-9 ; réimpressions octobre 2007 et novembre 2008 ISBN 978-2-7433-0482-9, p. 90 et 93.

- ^ "Commission nationale de toponymie – Collectivités territoriales françaises". Archived from the original on 12 November 2008.

- ^ a b Allen, Richard B. (14 October 1999). Slaves, Freedmen and Indentured Laborers in Colonial Mauritius. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521641258.

- ^ a b Tabuteau, Jacques (1987). Histoire de la justice dans les Mascareignes (in French). Paris: Océan éditions. p. 13. ISBN 2-907064-00-2. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ a b c Moriarty, Cpt. H.A. (1891). Islands in the southern Indian Ocean westward of Longitude 80 degrees east, including Madagascar. London: Great Britain Hydrographic Office. p. 269. OCLC 416495775.

- ^ "| Journal de l'île de la Réunion". Clicanoo.re. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ a b Asian and African Systems of Slavery. (1980). Storbritannien: University of California Press. p. 75-76

- ^ "Histoire - Assemblée nationale". www2.assemblee-nationale.fr. Archived from the original on 2 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ a b Asian and African Systems of Slavery. (1980). Storbritannien: University of California Press. p. 75-77

- ^ a b Raoul LUCAS et Mario SERVIABLE, C.R.I p. 26

- ^ Chris Murray: Unknown Conflicts of the Second World War – Forgotten Fronts, London/New York (NY): Routledge 2019, p. 97.

- ^ Sabado, Elsa (17 December 2013). "Quand Debré envoyait des enfants réunionnais dans la Creuse repeupler la France: le cinquantenaire oublié". Slate. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ Martial, Jean-Jacques (2003). Une enfance volée. Les Quatre Chemins. p. 113. ISBN 978-2-84784-110-7. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- ^ Géraldine Marcon (29 January 2014). "Chronologie: L'histoire des enfants réunionnais déplacés en métropole". ici, par France Bleu et France 3 (in French). Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- ^ "Island disease hits 50,000 people". BBC News. 2 February 2006. Archived from the original on 28 March 2009. Retrieved 18 August 2007.

- ^ Beesoon, Sanjay; Funkhouser, Ellen; Kotea, Navaratnam; Spielman, Andrew; Robich, Rebecca M. (2008). "Chikungunya Fever, Mauritius, 2006". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 14 (2): 337–338. doi:10.3201/eid1402.071024. PMC 2630048. PMID 18258136.

- ^ "Madagascar hit by mosquito virus". BBC News. 6 March 2006. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2007.

- ^ a b "Collectivités d'Outre-mer de l'article 73 de la Constitution (Guadeloupe, Guyane, Martinique, La Réunion, Mayotte)". legifrance.gouv.fr. Archived from the original on 2 July 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ Guy Dupont, Condé-sur-Noireau, L'Harmattan, juin 1990, 759 p. ISBN 2-7384-0715-3 p. 27

- ^ "Département de La Réunion (974)". INSEE. Retrieved 18 November 2024.

- ^ Populations légales 2019: 974 La Réunion Archived 12 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine, INSEE

- ^ a b "Forces armées dans la Zone-sud de l'océan Indien" [Armed Forces in the South Indian Ocean Zone] (in French). Ministère des Armées. Archived from the original on 24 November 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ Morcos, Pierre (1 April 2021). "France: A Bridge between Europe and the Indo-Pacific?". Center for Strategic & International Studies. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "French Rafales visit Reunion". DefenceWeb. 25 January 2022. Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "FAZSOI - Entraînement mutuel paille-en-queue 23.1 aux abords des côtes réunionnaises". DefenceWeb. 31 January 2023. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ Veron, Cynthia (21 June 2024). "GRAND ANGLE. Zoom sur le Panther, l'hélicoptère de la Marine Nationale". franceinfo (in French). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Groizeleau, Vincent (12 January 2024). "Le troisième patrouilleur d'outre-mer en phase d'armement à flot". Mer et Marine (in French). Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ Lagneau, Laurent (13 July 2024). "Océan Indien : Des drones Reaper pourront être ponctuellement déployés à La Réunion". Zone militaire. Retrieved 18 August 2024.

- ^ "Les DOM, défi pour la République, chance pour la France, 100 propositions pour fonder l'avenir (volume 2, comptes rendus des auditions et des déplacements de la mission)" [The overseas departments, challenge for the Republic, opportunity for France, 100 proposals to found the future (volume 2, reports of the hearings and trips of the mission)]. Sénat. 6 December 2022. Archived from the original on 7 November 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "Vedette Côtière de Surveillance Maritime (VCSM) Boats". Homelandsecurity Technology. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "Forces armées dans la Zone-sud de l'océan Indien". Ministère des Armées. Archived from the original on 24 November 2022. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- ^ [1] Archived 7 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine Le Piton du Confinement on clicanoo.com

- ^ Staudacher, Thomas (7 April 2007). "Reunion sees 'colossal' volcano eruption, but population safe". Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 9 April 2007. Retrieved 18 August 2007. (Web archive)

- ^ a b c Emmanuel Tessier, Saint Denis, Thèse de doctorat sous la direction de Pascale Chabanet et Catherine Aliaume, 2005, 254 p

- ^ Guy Dupont, Condé-sur-Noireau, L'Harmattan, juin 1990, 759 p. ISBN 2-7384-0715-3 p. 100.

- ^ "CLIMAT LA REUNION - Informations, normales et statistiques sur le climat à La Réunion". meteofrance.re. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Exceptionnel : Il a neigé au volcan". Imaz Press Réunion : l'actualité de la Réunion en photos (in French). 10 October 2006. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "European island outermost regions and climate change adaptation: a new role for regional planning" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization: Global Weather & Climate Extremes". Arizona State University. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "World: Greatest Twenty-four-Hour (1 Day) Rainfall". Arizona State University. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ "Lagon de l'Hermitage". Snorkeling Report. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ "The beaches of Réunion Island". Snorkeling Report. 13 September 2013. Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ^ "Flore de La Réunion". Habiter La Réunion (in French). Archived from the original on 31 July 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ (in French) L'Île de la Réunion.com: Le paille en queue Archived 29 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ David Wragg, Maéva Angélique Techer, Kamila Canale-Tabet, Benjamin Basso, Jean-Pierre Bidanel, Emmanuelle Labarthe, Olivier Bouchez, Yves Le Conte, Johanna Clémencet, Hélène Delatte, Alain Vignal (2018). "Autosomal and Mitochondrial Adaptation Following Admixture: A Case Study on the Honeybees of Reunion Island". Genome Biology and Evolution. 10 (1): 220–238. doi:10.1093/gbe/evx247. Retrieved 13 January 2025.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dr Sammy Ramsey. "The Tropilaelaps Mite: A Fate Far Worse Than Varroa". Retrieved 13 January 2025.

- ^ Olivier Esnault (2018). "Diversité des agents pathogènes de l'abeille dans le Sud-Ouest de l'Océan Indien dans un contexte d'invasion récente de Varroa destructor et mortalités associées" (PDF). Université de la Réunion. Retrieved 13 January 2025.

- ^ Benoit Jobart, Hélène Delatte, Gérard Lebreton, Nicolas Cazanove, Olivier Esnault, Johanna Clémencet, Nicolas Blot (2024). "Parasite and virus dynamics in the honeybee Apis mellifera unicolor on a tropical island recently invaded by Varroa destructor". Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 204. doi:10.1016/j.jip.2024.108125. Retrieved 13 January 2025.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Biodiversité marine Réunion, Hot spot". vieoceane.free.fr. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ "Crusta". crustiesfroverseas.free.fr. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Ronald Fricke, Thierry Mulochau, Patrick Durville, Pascale Chabanet, Emmanuel Tessier et Yves Letourneur, « », Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde A, Neue Serie, vol. 2, 2009, p. 1–168

- ^ Gilibert, Laurence (1 March 2018). "Crise requin: Les causes scientifiques sous les projecteurs de la revue "Nature"". Archived from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018 – via ZINFO974.

- ^ "Big Read: Reunion Island beset by shark controversy". News Corp Australia. 30 August 2013. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ^ Étude comparative des récifs coralliens de l'archipel des Mascareignes, station marine d'Endoume et Centre d'Océanographie, Marseille, et Centre Universitaire de La Réunion, Saint Denis de La Réunion, in : Guézé P. (dir.) Biologie marine et exploitation des ressources de l'Océan Indien occidental, Paris : ORSTOM, 1976, (47), p. 153-177.

- ^ "Pitons, cirques and remparts of Réunion Island". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 1 August 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ Dinerstein, Eric; et al. (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ^ ADUMITRESEI, LIDIA; STĂNESCU, IRINA (2009). "Theoretical Considerations upon the origin and nomenclature of the present rose cultivars". Journal of Plant Development. 16.

- ^ "History of Roses: Bourbon Roses" (PDF). American Rose Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ C. Gabrié, « », Initiative Française pour les récifs coralliens (Ifrecor), 1998, p. 136