I-400-class submarine

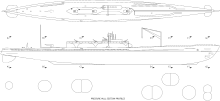

I-401, with its long plane hangar and forward catapult | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Operators | |

| Cost | 28,861,000 JPY in 1942[1] |

| Built | 18 January 1943–24 July 1945 |

| In commission | 1944–45 |

| Planned | 18 |

| Completed | 3 |

| Cancelled | 15 |

| Retired | 3 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Submarine aircraft carrier |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 122 m (400 ft) |

| Beam | 12.0 m (39.4 ft) |

| Draft | 7.0 m (23.0 ft) |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed |

|

| Range | 43,123 mi. (69,400km) |

| Test depth | 100 m (330 ft) |

| Complement | 144 officers and men |

| Armament |

|

The I-400-class submarine (伊四百型潜水艦, I-yon-hyaku-gata sensuikan) Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) submarines were the largest submarines of World War II, with the first one completed just a little over a month before the end of the war. The I-400s remained the largest submarines ever built until the construction of nuclear ballistic missile submarines in the 1960s. The IJN called this type of submarine Sentoku type submarine (潜特型潜水艦, Sen-Toku-gata sensuikan, Submarine Special). The type name was shortened to Toku-gata Sensuikan (特型潜水艦, Special Type Submarine). They were submarine aircraft carriers able to carry three Aichi M6A Seiran aircraft underwater to their destinations. They were designed to surface, launch their planes, then quickly dive again before they were discovered. They also carried torpedoes for close-range combat.

The I-400 class was designed with the range to travel anywhere in the world and return. A fleet of 18 boats was planned in 1942, and work started on the first in January 1943 at the Kure, Hiroshima arsenal. Within a year the plan was scaled back to five, of which only three (I-400 at Kure, and I-401 and I-402 at Sasebo) were completed.

Origins

The I-400 class was the brainchild of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander-in-Chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet. Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, he conceived the idea of taking the war to the United States mainland by making aerial attacks against cities along the U.S. western and eastern seaboards using submarine-launched naval aircraft. He commissioned Captain Kameto Kuroshima to make a feasibility study.[3]

Yamamoto submitted the resulting proposal to Fleet Headquarters on 13 January 1942. It called for 18 large submarines capable of making three round-trips to the west coast of the United States without refueling or one round-trip to any point on the globe. They also had to be able to store and launch at least two attack aircraft armed with one torpedo or 800 kg (1,800 lb) bomb. By 17 March, general design plans for the submarines were finalized. Construction of I-400 commenced at Kure Dock Yards on 18 January 1943, and four more boats followed: I-401 (April 1943) and I-402 (Oct 1943) at Sasebo; I-403 (Sept 1943) at Kobe and I-404 (February 1944) at Kure. Only three were completed.[4]

Following Yamamoto's death in April 1943, the number of aircraft-carrying submarines to be built was reduced from eighteen to nine, then five and finally three. Only I-400 and I-401 actually entered service; I-402 was completed on 24 July 1945, five weeks before the end of the war, but never made it to sea.[4]

Design features and equipment

Each submarine had four 1,680 kW (2,250 hp) engines and carried enough fuel to go around the world one-and-a-half times—more than enough to reach the United States travelling east or west. Measuring more than 120 m (390 ft) long overall, they displaced 5,900 t (6,500 short tons), more than double their typical American contemporaries. The cross-section of its pressure hull had a unique figure-of-eight shape which afforded the necessary strength and stability to handle the weight of a large on-deck aircraft hangar. To allow stowage of three aircraft along the vessel's centreline, the conning tower was offset to port.[5]

Located approximately amidships on the top deck was a cylindrical watertight aircraft hangar, 31 m (102 ft) long and 3.5 m (11 ft) in diameter. The outer access door could be opened hydraulically from within or manually from the outside by turning a large hand-wheel connected to a rack and spur gear. The door was made waterproof with a 51-millimetre-thick (2.0 in) rubber gasket.[5][6]

Situated atop the hangar were three waterproofed Type 96 triple-mount 25 mm (1 in) autocannon for AA defence, two aft and one forward of the conning tower. A single 25 mm (1 in) autocannon on a pedestal mount was also located just aft the bridge. One Type 11, 140 mm (5.5 in) deck gun was positioned aft of the hangar. It had a range of 15 km (9.3 mi).[7]

Eight torpedo tubes were mounted in the bow, four above and four below. There were no aft tubes.[5][8]

Stowed in an open recessed compartment on the forward port side, just below top deck, was a collapsible crane used to retrieve the submarine's Seiran floatplanes. The crane had an electrically operated hoist and was capable of lifting approximately 4.5 t (5.0 short tons). It was raised mechanically to a height of 8 m (26 ft) via a motor inside the boat. The boom extended out to a length of 11.8 m (39 ft).[9]

A special trim system was fitted to the boats, allowing them to loiter submerged and stationary while awaiting the return of their aircraft. However, operation of this system was noisy and its usefulness was in doubt.[5][10]

Strung along the submarine's gunwales were two parallel sets of demagnetization cables, running from the stern to the bow planes. They were meant to protect against magnetic mines, by nullifying the magnetic field which normally triggers the mines fusing system. A similar demagnetizing system was carried on many Japanese surface ships during the first part of the war, until they were later removed during refitting.[11]

Electronics on board the I-400s included a Mark 3 Model 1 air search radar equipped with two separate antennas. This unit was capable of detecting aircraft out to a range of 80 km (43 nmi). The boats were also equipped with Mark 2 Model 2 air/surface radar sets with distinctive horn-shaped antennas. Each boat carried an E27 radar warning receiver, connected to both a trainable dipole antenna and a fixed non-directional antenna made up of a wire mesh basket and two metal rods.[12]

The submarines were equipped with two periscopes of German manufacture, about 12.2 m (40 ft) long, one for use during daylight and the other at night.[13]

A special anechoic coating made from a mixture of gum, asbestos, and adhesives was applied to the hulls from the waterline to the bilge keel. This coating was apparently based on German research, though completely different in composition from German anechoic tiles such as Alberich or Tarnmatte.[14] This was intended to absorb or diffuse enemy sonar pulses and dampen reverberations from the boat's internal machinery, theoretically making detection while submerged more difficult, though its effectiveness was never conclusively established.[14][15][16]

In May 1945, I-401 was fitted with a German-supplied snorkel, a hydraulically raised air intake device allowing the boat to run its diesel engines and recharge its batteries while remaining at periscope depth. This retrofit occurred while the boat was laid up at Kure for repairs after being damaged by an American mine in April.[17]

I-402 was completed shortly before the war ended, but had been converted during building to a tanker and was never equipped with aircraft.[18]

Characteristics

The I-400-class subs were unwieldy and relatively difficult to maneuver while surfaced owing to their small rudders.[19] The large superstructure also caused the sub to veer off course during any strong wind.[19] The maximum safe diving depth of the I-400-class submarine was only 82% of its overall length, which presented problems if the submarine dived at too steep an angle in an emergency.[19] Because of their large aircraft hangars and conning tower, all I-400-class boats had significant visual and radar signatures on the surface, and could be detected by aircraft relatively easily. Dive time was 56 seconds, nearly double that of U.S. fleet subs, which made the boats easier to destroy from the air when caught on the surface.[19]

When submerged and traveling at a slow speed of two knots, the offset superstructure forced the helmsman to steer seven degrees starboard in order to steer a straight course.[19] When conducting a torpedo attack the captain had to take into account his larger turning circle to starboard than to port, again because of the offset design.[19] Like other Japanese submarines, crew members in I-400 subs had no air conditioning to control temperatures in tropical waters and no flush toilets.[19] Lack of cold storage greatly limited the crew's diet, while inadequate sleeping quarters forced some of the crew to sleep on the decks or in passageways.[19]

Aircraft

The hangar of the I-400s was originally designed to hold two aircraft. In 1943, however, Commander Yasuo Fujimori, Submarine Staff Officer of the Naval General Staff, requested it be enlarged. This was deemed feasible and, as remodelled, I-400s could stow up to three Aichi M6A Seiran floatplanes.[20]

The Seiran was specifically designed for use aboard the submarines and could carry an 800 kg (1,800 lb) bomb, with a range of 1,000 km (620 mi) at 475 km/h (295 mph). To fit inside the narrow confines of the hangar, the floats were removed and stowed, the wings rotated 90 degrees and folded backward hydraulically against the fuselage, the horizontal stabilizers folded down and the top of the vertical stabilizer folded over so the overall forward profile of the aircraft was within the diameter of its propeller. When deployed for flight, the aircraft had a wingspan of 12 m (39 ft) and a length of 11.6 m (38 ft). A crew of four could prepare and launch all three in 30 minutes (or 15 minutes if the planes' pontoons were not first attached, which would make recovery impossible).[21] As the Seiran would normally be launched at night, parts and areas of the plane were coated with luminescent paint to ease assembly in the dark.[22]

The Seirans were launched from a 26 m (85 ft) Type 4 No. 2 Model 10 compressed-air catapult on the forward deck of the submarine. Underneath the catapult track were four high-pressure air flasks connected in parallel to a piston. The aircraft, mounted atop collapsible carriages via catapult attachment points along their fuselages, would be slung 70–75 feet along the track, though the piston itself only moved between eight and ten feet during operation.[23]

Two sets of pontoons for the Seirans were stored in special watertight compartments located just below the main deck on either side of the catapult track. From there they could be quickly slid forward on ramps and attached to the plane's wings. A third set of pontoons and additional spares were kept inside the hangar.[5][24]

The aircraft were to be launched by catapult, and fly their missions. The launching submarine was to submerge and stay in place to allow the aircraft to navigate back to the area by dead reckoning, where it would land on the water with its floats, and be hoisted back aboard by crane. Overall the system was the same as used by Japanese Navy cruisers and light cruisers when launching their reconnaissance floatplanes (like the Aichi E13A), only with aircraft specially designed for use with the I-400 class submarine, and with the added complexity of having to locate a submerged and hidden vessel on return from the mission.

Although this was the typical mode of operation, in cases where fast launching and recovery was essential for escape (see below), the floatplanes could be launched without their floats, and ditched upon landing, saving the time spent recovering and re-hangaring the aircraft, which was a complex and lengthy procedure. This had the added benefit of eliminating the weight and considerable drag of the large and bulky floats, which in turn increased the speed and range of the aircraft, but made any recovery of the aircraft after completing the mission impossible. (For a similar defensive measure involving catapult-launched, disposable aircraft used by Allied convoy groups in the Battle of the Atlantic, see CAM ship.) In extreme circumstances, the aircraft could theoretically be launched and abandoned altogether while the submarine beat a hasty retreat, leaving the crews to fly their missions with no hope of return, perhaps as a kamikaze mission.

Operational history

As the war turned against the Japanese and their fleet no longer had free rein in the Pacific, the Commander-in-Chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, devised a daring plan to attack New York, Washington D.C., and other large American cities.[citation needed]

Panama Canal strike

Following an inspection of Rabaul in August 1943, Captain Chikao Yamamoto and Commander Yasuo Fujimori conceived the idea of using the sen toku (secret submarine attack) to destroy the locks of the Panama Canal in an attempt to cut American supply lines to the Pacific Ocean and hamper the transfer of U.S. ships. Intelligence gathering on the proposed target began later that year.[20]

The Japanese were well aware that American fortifications existed on both sides of the Canal. On the Atlantic, the large coastal artillery batteries of Fort Sherman had a range of 30,000 yards (17 miles (27 km)), preventing enemy ships from getting near enough to shell the locks. In the months following the attack on Pearl Harbor, air and sea patrols had been strengthened around both entrances, and barrage balloons and anti-submarine nets erected. In August 1942, the 88th Coast (Anti-Aircraft) Artillery unit was added to help defend against aerial attacks.[20]

As the war continued and Japan's fortunes declined, however, security around the Canal grew increasingly lax. In January 1944 Commander Fujimori personally interviewed an American prisoner-of-war who had done guard duty there. He told Fujimori that defensive air patrols had virtually ceased, since it was considered increasingly unlikely the Axis powers would ever attack the locks. This further convinced Fujimori of his plan's feasibility.[25]

A Japanese engineer who had worked on the Canal during its construction handed over hundreds of documents to the Naval General Staff, including blueprints of the Canal structures and construction methods. A team of three shipping engineers studied the documents and concluded that the locks at Miraflores on the Pacific side were the most vulnerable to aerial bombing, but the Gatun locks on the Atlantic side offered a chance of causing greater damage, since it would be harder to halt any outflow of water. They estimated the Canal would be unusable for at least six months following a successful attack on the locks.[26]

To increase the size of the airborne attack force, Commander Fujimori requested that two additional fleet submarines still under construction at Kobe, I-13 and I-14, be modified to house two Seirans each, bringing the total number of planes available to ten.[20] It was originally planned that two of the Seirans would carry torpedoes and the other eight would carry 800 kg (1,800 lb) bombs. They were to make a combined torpedo and glide-bombing attack against the Gatun Locks. Eventually though, torpedo-bombing was dispensed with, because only one Seiran pilot had mastered the technique.[27]

The Panama Canal strike plan called for four aircraft-carrying submarines (I-400, I-401, I-13 and I-14) to sail eastward across the Pacific to the Gulf of Panama, a journey expected to take two months. At a point 185 km (100 nmi) off the coast of Ecuador, the submarines would launch their Seiran aircraft at 0300hrs on a moonlit night. The Seirans, without floats, would fly at an altitude of 4,000 m (13,000 ft) across the northern coast of Colombia to the vicinity of Colón. Now on the Caribbean side of the isthmus, they would turn westward on a heading of 270 degrees, then angle south-west and make their final approach to the Canal locks at dawn. After completing their bombing runs, the Seirans were to return to a designated rendezvous point and ditch alongside the waiting submarines where the aircrews would be picked up.[28]

Around April 1945, Captain Ariizumi, the man appointed to carry out the attack, decided the Seiran pilots would make kamikaze ramming attacks against the gates, rather than conventional bombing runs, a tactic becoming increasingly common as the war went against the Japanese. The Seiran squadron leader had already suggested as much to Ariizumi earlier that month, though for a time this was kept secret from the other pilots. At the end of May, however, one pilot happened to observe a Seiran having its bomb-release mechanism removed and replaced with a fixed mount. Realizing the implications of this change, he angrily confronted the executive officer of the squadron, who explained that the decision to withhold this intention from the other men was made to "avoid mental pressures on the aircrews."[29]

By 5 June 1945, all four aircraft-carrying submarines had arrived at Nanao Wan where a full-scale wooden model of the Gatun Locks gate had been built by the Maizuru Naval Arsenal, placed on a raft and towed into the bay. The following night, formal training commenced with the Seiran flight crews practising rapid assembly, catapult launch and recovery of their aircraft. There was also rudimentary formation flying. From 15 June the Seiran pilots made practice daylight bombing runs against the wooden gate mock-up. By 20 June, all training ended and the operation was set to proceed.[30]

Ulithi atoll

Before the attack could commence, Okinawa fell, and word reached Japan that the Allies were preparing an assault on the Japanese home islands. The Japanese Naval General Staff concluded the Panama Canal attack would have little impact on the war's outcome, and more direct and immediate action was necessary to stem the American advance.

Fifteen American aircraft carriers had assembled at the Ulithi atoll, preparatory to making a series of raids against the home islands.[30] The Japanese mission was changed to an attack on the Ulithi base.

The attack on Ulithi Atoll was to take place in two phases. The first, codenamed Hikari (light), involved transporting four C6N Saiun (Myrt) single-engined high-speed reconnaissance planes to Truk Island. They were to be disassembled, crated and loaded into the water-tight hangars of submarines I-13 and I-14. Upon reaching Truk, the Saiuns would be unloaded, reassembled and then flown over Ulithi to confirm the presence of American carriers anchored there. Following the delivery, I-13 and I-14 were to sail for Hong Kong, where they would embark four Seiran attack planes. They would then head to Singapore and join I-400 and I-401 for further operations.[31]

The second phase of the Ulithi attack was codenamed Arashi (storm). I-400 and I-401 were to rendezvous at a predetermined point on the night of 14/15 August. On 17 August they would launch their six Seirans before daybreak on a kamikaze mission against the American carriers. The Seirans, each with an 800 kg (1,800 lb) bomb bolted to its fuselage, were to fly less than 50 m (160 ft) above the water to avoid radar detection and the American fighters expected to be patrolling 4,000 m (13,000 ft) above.[32]

Just before departing Maizuru Naval Station, the Seirans were completely over-painted in silver with American stars and bars insignias covering the red Hinomarus, a direct violation of the rules of war. This was an attempt to further confuse recognition if the aircraft were prematurely spotted, but it was not well received by the pilots. Some felt it was both unnecessary and a personal insult to fly under American markings, as well as dishonorable to the Imperial Navy.[33]

Following the attack on Ulithi, I-400 and I-401 would sail for Hong Kong. There they would take on six more Seirans and sail for Singapore, where fuel oil was more readily available. They would then join I-13 and I-14 and stage further attacks with a combined force of ten Seiran aircraft.[31]

On 22 June, I-13 and I-14 arrived at Maizuru Harbor to take on fuel. They reached Ominato on 4 July to pick up their Saiun reconnaissance aircraft. I-13 departed for Truk on 11 July but never reached her destination. She was detected running on the surface, attacked, and damaged by radar-equipped TBM Avengers on 16 July. An American destroyer escort later arrived and sank her with depth charges.[34]

Japan surrendered before the Ulithi attack was launched, and on 22 August 1945, the crews of the submarines were ordered to destroy all their weapons. The torpedoes were fired without arming and the aircraft were launched without unfolding the wings and stabilizers. When I-400 surrendered to the American destroyer, Blue, the U.S. crew was astounded at her size, nearly 24 ft (7.3 m) longer than the USS Blue and just as wide – considerably longer and wider than the largest American fleet submarine of the day.

Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night

The Japanese conceived of an attack on the United States through the use of biological weapons specifically directed at the civilian population in San Diego, California. Dubbed "Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night", the plan was to launch aircraft from five I-400 submarines near Southern California at night, who would then drop "infected flea" bombs on the intended target, in the hope that the resulting infection would spread to the entire Western seaboard and kill tens of thousands of people. The plan was scheduled for September 22, 1945, but Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945, before the operation was carried out.[35][36]

American inspections

The U.S. Navy boarded and recovered 24 submarines, including the three I-400 submarines, taking them to Sasebo Bay to study them. While there, they received a message that the Soviets were sending an inspection team to examine the submarines. To prevent this, Operation Road's End was instituted. Most of the submarines were taken to a position designated as Point Deep Six, about 35 km (19 nmi) southeast of Fukue Island,[37] packed with charges of C-3 explosive and destroyed; they sank to a depth of 200 m (660 ft).

Four remaining submarines, I-400, I-401, I-201 and I-203, were sailed to Hawaii by U.S. Navy technicians for further inspection. Upon completion of the inspections, the submarines were scuttled in the waters off Kalaeloa near Oahu in Hawaii by torpedoes from US submarine USS Trumpetfish on June 4, 1946, to prevent the technology from being made available to the Soviets who were demanding access to them. Dr. James P. (Jim) Delgado of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's maritime heritage program reported that the official government position that the exact location of the sinking was unknown, but has been confirmed by declassified US Navy documents.[38]

Artifacts

The wreckage of I-401 was discovered by the Pisces deep-sea submarines of the Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory in March 2005 at a depth of 820 metres (2,690 ft).[39][40][41] It was reported that I-400 was later found by the same team off the southwest coast of the Hawaiian island of Oahu in August 2013[42][43] at a depth of 700 metres (2,300 ft).[44] NOAA researcher Jim Delgado, working aboard Pisces V, told the Chicago Tribune "It was torpedoed, partially collapsed and had sunk at a steep angle."[45] The submarines scuttled off the Japanese coast were located in July 2015.[37]

A restored Seiran airplane is displayed at the National Air and Space Museum's Udvar-Hazy Center in suburban Washington, D.C. It is the only surviving example of this aircraft, and was found at the Aichi Aircraft Factory following the end of the war in August 1945. Shipped to Naval Air Station Alameda, it was left on outdoor display until 1962, when it was transferred to the Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility in Silver Hill, Maryland. There it remained in storage until 1989, when a comprehensive restoration effort was mounted. Though the plane had been ravaged by weather and souvenir collectors, and original factory drawings were lacking, the restoration team was able to reconstruct it accurately, and by February 2000 it was ready for display.[23]

Boats in class

| Boat num. | Boat | Builder | Laid down | Launched | Completed | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-400 | 5231 | Kure Naval Arsenal | 18 Jan 1943 | 18 Jan 1944 | 30 Dec 1944 | Captured by USS Blue, 19 Aug 1945; decommissioned 15 Sep 1945; sunk as a target off the Hawaiian Islands by USS Trumpetfish, 4 Jun 1946; The wreck of I-400, along with that of USS Kailua (IX-71), was found and confirmed off Oahu in 2013 during dives of Pisces V searching for marine heritage sites[46] |

| I-401 | 5232 | Sasebo Naval Arsenal | 26 Apr 1943 | 11 Mar 1944 | 8 Jan 1945 | Captured by USS Segundo, 29 (or 30) August 1945; decommissioned 15 Sep 1945; sunk as a target off the Hawaiian Islands, 31 May 1946 |

| I-402 | 5233 | Sasebo Naval Arsenal | 20 Oct 1943 | 5 Sep 1944 | 24 Jul 1945 | Converted to a tanker submarine, June 1945;[47][48] decommissioned, 15 Nov 1945; sunk as a target off the Gotō Islands, 1 Apr 1946 |

| I-403 | 5234 | — | — | — | — | Cancelled October 1943 |

| I-404 | 5235 | Kure Naval Arsenal | 8 Nov 1943 | 7 Jul 1944 | — | Construction stopped (95% complete), 4 Jun 1945; Heavily damaged by air raid, 28 Jul 1945; later scuttled; Salvaged and scrapped, 1952 |

| I-405 | 5236 | Kawasaki, Senshū Shipyard | 27 Sep 1943 | — | — | Construction stopped and scrapped |

| I-406 – I-409 | 5237 – 5240 | — | — | — | — | Cancelled October 1943 |

| I-410 – I-417 | 5241 – 5248 | — | — | — | — | Cancelled July 1943 |

See also

- Type A Mod.2 submarine IJN two-aircraft submarine seaplane carrier

- Submarine aircraft carrier

- French submarine Surcouf

References

Notes

- ^ Senshi Sōsho #88 (1975), p.37

- ^ Campbell, John Naval Weapons of World War Two ISBN 0-87021-459-4 p.191

- ^ Sakaida, p. 15.

- ^ a b Sakaida, p. 16.

- ^ Sakaida, p.74.

- ^ Sakaida, p.100-101.

- ^ Sakaida, p. 17.

- ^ Sakaida, p. 81.

- ^ Layman and McLaughlin, p. 178–179.

- ^ Sakaida, p. 73.

- ^ Sakaida, p. 104-107.

- ^ Sakaida, p. 104.

- ^ a b Boyd, Carl, and Yoshida, Akihiko, The Japanese Submarine Force and World War II, BlueJacket Books (2002), ISBN 1557500150, pp. 27, 29

- ^ Sakaida, p. 92.

- ^ Sakaida, p. 126.

- ^ Orita, p. 317

- ^ Hashimoto, p. 213

- ^ a b c d e f g h Paine, Thomas O., I Was A Yank On A Japanese Sub, U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, Volume 112, Number 9, Issue 1003 (September 1986), p. 73-78

- ^ a b c d Sakaida, p. 36

- ^ Air International October 1989, p. 187.

- ^ Francillon, p. 292

- ^ a b Sakaida, p.134

- ^ Sakaida, p. 82

- ^ Sakaida, p. 44.

- ^ Sakaida, p. 44–5.

- ^ Sakaida, pp. 45–6.

- ^ Sakaida, pp. 46–7.

- ^ Sakaida, pp. 46–9.

- ^ a b Sakaida, p. 49.

- ^ a b Sakaida, p. 51.

- ^ Sakaida, p. 52.

- ^ Sakaida, p. 53.

- ^ Sakaida, p. 57.

- ^ Amy Stewart (April 25, 2011). "Where To Find The World's Most 'Wicked Bugs' - Fleas". National Public Radio.

- ^ Russell Working (June 5, 2001). "The trial of Unit 731". The Japan Times.

- ^ a b "24 scuttled Imperial Japanese Navy submarines found off Goto Islands". The Japan Times. 8 August 2015.

- ^ Louis Lucero II, "Finding Japan's Aircraft Carrier Sub", The New York Times, 2013-12-03, p. D3.

- ^ "Imperial Submarines". www.combinedfleet.com.

- ^ "Imperial Submarines". www.combinedfleet.com.

- ^ I-401 Submarine Found off of Barbers Point Archived 2005-04-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "World War Two era Japanese submarine found off Hawaii coast". reuters.com. 3 December 2013.

- ^ Whitfield, Bethany (5 May 2015). "Video/Photos: Divers Discover Sunken Submarine's Airplane Hangar". Flying. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ^ Louis Lucero II, "Finding Japan's Aircraft-Carrier Sub," The New York Times, 2013-12-03, p. D3.

- ^ "WWII era Japanese submarine found off Hawaii coast". Chicago Tribune. December 3, 2013.

- ^ Delgado, James P. (March 2014). "Voyage of Rediscovery". Naval History Magazine. 28 (2). Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ Senshi Sōsho #88 (1975), p.272

- ^ Rekishi Gunzō, p83, P85

Bibliography

- Francillon, R.J. Japanese Aircraft of the Pacific War. London:Putnam, 1970. ISBN 0-370-00033-1.

- Geoghegan, John J. Operation Storm: Japan's Top Secret Submarines and Its Plan to Change the Course of World War II. Crown Publishers, NY, 2013. ISBN 978-0-307-46480-4.

- Hashimoto, Mochitsura. Sunk!. Henry Holt and Company, 1954.

- Layman, R.D. and Stephen McLaughlin. The Hybrid Warship. London:Conway Maritime Press, 1991. ISBN 0-85177-555-1.

- Orita, Zenji and Joseph D. Harrington. I-Boat Captain. Major Books, 1976. ISBN 0-89041-103-4

- Sakaida, Henry and Gary Nila, Koji Takaki. I-400: Japan's Secret Aircraft-Carrying Strike Submarine. Hikoki Publications, 2006. ISBN 978-1-902109-45-9

- "Rekishi Gunzō"., History of Pacific War Vol. 17 I-Gō Submarines, Gakken (Japanese publishing company), January 1998, ISBN 4-05-601767-0

- The Maru Special, Japanese Naval Vessels No.13, Japanese submarine I-13 class and I-400 class, Ushio Shobō (Japanese publishing company), July 1977

- The Maru Special, Japanese Naval Vessels No.132, Japanese submarines I, Ushio Shobō (Japanese publishing company), February 1988

- Senshi Sōsho, Vol. 88 Naval armaments and war preparation (2), "And after the outbreak of war", Asagumo Simbun (Japan), October 1975

External links

- About I-400

- WW2DB: I-400-class Submarines

- Discovery of I-401 wreckage off Hawai

- Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory report

- An I-400 article from a site named "Damn Interesting"

- Story of the transpacific voyage of I-400

- Japan's WWII Monster Sub: How the deadly Sen-Toku mission almost succeeded Archived 2010-04-20 at the Wayback Machine

- I-400

- Secrets of the Dead: Japanese SuperSub - PBS documentary on the development and use of the I400-class submarine

- [1] - CNN - Researchers in Hawaii find lost Japanese World War II mega-sub

- Historic footage of I-400 (boat 5231) during Japanese surrender operations to US Navy, September, 1945

- Historic footage: Scuttling of Japanese submarine I-400 (boat 5231) off coast of Hawaii by torpedo from USS Trumpetfish, June 4, 1946.