2004 Pacific hurricane season

| 2004 Pacific hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 22, 2004 |

| Last system dissipated | October 26, 2004 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Javier |

| • Maximum winds | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 930 mbar (hPa; 27.46 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 17, 1 unofficial |

| Total storms | 12 |

| Hurricanes | 6 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 3 |

| Total fatalities | None, 3 missing |

| Total damage | None |

| Related articles | |

The 2004 Pacific hurricane season was an overall below-average Pacific hurricane season in which there were 12 named tropical storms, all of which formed in the eastern Pacific basin (east of 140°W and north of the equator). Of these, 6 became hurricanes, and 3 of those intensified into major hurricanes. No storms made landfall in 2004, the first such occurrence since 1991. In addition to the season's 12 named storms, there were five tropical depressions that did not reach tropical storm status. One of them, Sixteen-E, made landfall in northwestern Sinaloa. The season officially began on May 15 in the eastern Pacific, and on June 1 in the central Pacific basin (between140°W and the International Date Line, north of the equator). It officially ended in both basins on November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period during each year when most tropical cyclones form in each respective basin.[1] These dates conventionally delimit the period during each year when a majority of tropical cyclones form. The season was reflected by an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index of 71 units.

Impact throughout the season was minimal and no deaths were recorded. In early August, the remnants of Hurricane Darby contributed to localized heavy rainfall in Hawaii, causing minor street and stream flooding; coffee and macadamia trees were damaged as well. In early September, Hurricane Howard resulted in significant flooding across the Baja California peninsula that damaged agricultural land and 393 homes. Large swells also resulted in about 1,000 lifeguard rescues in California. In mid-September, Javier, the strongest hurricane of the season, caused three fishermen to go missing and helped alleviate a multi-year drought across the Southwest United States. It produced record rainfall in the state of Wyoming. In mid- to late October, Tropical Storm Lester and Tropical Depression Sixteen-E each dumped heavy rain upon parts of Mexico, resulting in minor flood and mudslide damage.

Seasonal forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

Ref |

| Average (1966–2003) | 16 | 9 | 3 | ||

| Record high activity | 27 | 16 (tie) | 11 | ||

| Record low activity | 8 (tie) | 3 | 0† (tie) | ||

| SMN | January 2004 | 15 | 6 | 3 | [2] |

| SMN | May 17, 2004 | 14 | 7 | 2 | [3] |

| NOAA | May 21, 2004 | 13–15 | 6-8 | 2-4 | [4] |

| SMN | August 2004 | 13 | 6 | 3 | [5] |

| Actual activity |

12 | 6 | 3 | ||

In January 2004, the Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (SMN) released their first prediction for tropical cyclone activity throughout the Northeast Pacific. Based on a Neutral El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), a total of 15 named storms, 6 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes was forecast.[2] These values were slightly altered in May to 14 named storms, 7 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes,[3] and again in August to 13 named storms, 6 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes.[5]

On May 17, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration issued its seasonal forecast for the 2004 central Pacific season, predicting four or five tropical cyclones to form or cross into the basin. Likewise to the SMN, near average activity was expected largely as a result of a Neutral ENSO.[6] The organization issued its experimental eastern Pacific outlook on May 21, highlighting a 45 percent change of below-average activity, 45 percent chance of near-average activity, and only a 10 percent chance of above-average activity in the basin. A total of 13 to 15 named storms, 6 to 8 hurricanes, and 2 to 4 major hurricanes was forecast.[4]

Seasonal summary

| Rank | Season | ACE value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1977 | 22.3 |

| 2 | 2010 | 51.2 |

| 3 | 2007 | 51.6 |

| 4 | 1996 | 53.9 |

| 5 | 2003 | 56.6 |

| 6 | 1979 | 57.4 |

| 7 | 2004 | 71.1 |

| 8 | 1981 | 72.8 |

| 9 | 2013 | 74.8 |

| 10 | 2020 | 77.3 |

Activity was below average throughout the season. Altogether there were 12 named storms, 6 of which became hurricanes, and 3 of those intensified into major hurricanes, compared to the long-term average of 16 named storms, 9 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes.[8]

The season's first storm, Agatha, developed on May 22.[9] No tropical cyclones developed during June, below the average of 2 named storms and 1 hurricane, and also the first time since 1969 that the month was cyclone-free.[10] The first hurricane of the season was Celia, which briefly reached Category 1 strength on July 22.[11] It was soon followed by Darby, the first major Hurricane of the season and the first in the Eastern Pacific since Kenna in 2002.[12] Later, on September 14, Javier attained sustained winds of 150 mph (240 km/h), making it the strongest hurricane of the season.[13]

Overall wind energy output was reflected with an ACE index value of 71 units for the season.[14] Although vertical wind shear was near average and ocean temperatures were slightly warmer than average south of Mexico, anomalously cool waters and drier than average air mass existed in the central portions of the eastern Pacific. Anomalously strong mid-level ridging extending from the Atlantic to northern Mexico steered a majority of the season's cyclones toward this inhospitable region and also acted to steer all the system of tropical storm intensity or stronger away from land.[15]

Systems

Tropical Storm Agatha

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 22 – May 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 997 mbar (hPa) |

A nearly stationary trough stretched from the eastern Pacific into the eastern Caribbean Sea during mid-May. An ill-defined tropical wave crossed Central America on May 17 and interacted with the trough, eventually leading to the formation of a tropical depression at 00:00 UTC on May 22. The newly formed cyclone moved northwest parallel to the coastline of Mexico while steadily organizing in a low wind shear regime, intensifying into Tropical Storm Agatha by 12:00 UTC that day and attaining peak winds of 60 mph (97 km/h) twelve hours later. Increasingly cool ocean temperatures and a drier air mass caused Agatha to weaken quickly thereafter, and it degenerated into a remnant low by 12:00 UTC on May 24. The post-tropical cyclone drifted aimlessly before dissipating well south of the Baja California Peninsula on May 26.[9]

Tropical Depression Two-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 2 – July 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1007 mbar (hPa) |

A westward-moving tropical wave from Africa crossed Central America into the eastern Pacific in late June, coalescing into a tropical depression at 12:00 UTC on July 2 well southwest of the southern tip of the Baja California Peninsula.[16] Steered westward by low-level flow, the depression failed to organize amid wind shear and cooler sea surface temperatures,[17] instead degenerating into a remnant low at 00:00 UTC on July 4. The post-tropical cyclone dissipated a day later.[16]

Tropical Depression One-C

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 5 – July 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 30 mph (45 km/h) (1-min); 1007 mbar (hPa) |

An organized region of convection within the Intertropical Convergence Zone developed into a tropical depression at 03:00 UTC on July 5 while located roughly 700 mi (1,100 km) south-southeast of Johnston Atoll, becoming the farthest-south-forming central Pacific tropical cyclone since Tropical Storm Hali (1992). Steered westward, the depression failed to intensify due to its quick forward motion despite a seemingly favorable environment, and it quickly dissipated at 00:00 UTC on July 6.[18]

Tropical Storm Blas

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 12 – July 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 991 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave crossed Central America on July 8, developing into a tropical depression at 12:00 UTC on July 12 while located about 335 mi (539 km) southwest of Zihuatanejo, Mexico; six hours later, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Blas. Steered swiftly northwestward around a mid-level ridge over the southwestern United States, the cyclone steadily intensified and reached peak winds of 65 mph (105 km/h) early on July 13 as a large and robust convective canopy became evident. Blas began a steady weakening trend as it tracked over increasingly cool sea surface temperatures, weakening to a tropical depression at 18:00 UTC on July 14 and degenerating into a large remnant low twelve hours later. The post-tropical cyclone decelerated and curved northeastward, dissipating well west of central Baja California early on July 19.[19]

Hurricane Celia

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 19 – July 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); 981 mbar (hPa) |

A vigorous tropical wave entered the East Pacific on July 13, acquiring sufficient organization to be declared a tropical depression at 00:00 UTC on July 19 while located about 620 mi (1,000 km) south-southwest of the southern tip of the Baja California Peninsula. Directed west-northwest around a subtropical ridge, the cyclone steadily intensified amongst a favorable environment, becoming Tropical Storm Celia at 12:00 UTC that same day and further strengthening into a Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale, the season's first, at 00:00 UTC on July 22. After attaining peak winds of 85 mph (137 km/h) six hours later, an increasingly unfavorable environment began to hinder the system. Celia weakened to a tropical storm at 18:00 UTC on July 22 and eventually degenerated into a remnant low at 00:00 UTC on July 26. The post-tropical cyclone dissipated about 1,740 mi (2,800 km) west-southwest of the southern tip of the Baja California Peninsula later that morning.[20]

Hurricane Darby

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 26 – August 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min); 957 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical depression formed at 12:00 UTC on July 26 while positioned about 760 mi (1,220 km) south-southwest of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico from a tropical wave that entered the eastern Pacific nearly a week prior. The system quickly intensified as it curved west-northwest around a subtropical ridge, becoming Tropical Storm Darby at 00:00 UTC on July 27 and strengthening into a Category 1 hurricane early the next day. After attaining its peak as the season's first major hurricane with winds of 120 mph (190 km/h), increasing wind shear and cooler sea surface temperatures begin to weaken the cyclone. It weakened to a tropical storm at 12:00 UTC on July 30 and further to a tropical depression a day later as it entered the jurisdiction of the Central Pacific Hurricane Center.[12] At 12:00 UTC on August 1, Darby dissipated about 850 mi (1,370 km) east of the Hawaiian Islands.[18]

Although Darby produced no impacts to land as a tropical cyclone, its remnant moisture field combined with an upper-level trough over Hawaii to produce an unstable atmosphere. General rainfall amounts of 2–5 in (51–127 mm) were recorded across the Big Island and Oahu, with a localized peak of 9.04 in (230 mm) in Kaneohe; this led to flooding and several road closures. Minor stream flooding was observed on the southeast flank of Mount Haleakalā. A rainfall total of 3.06 in (78 mm) was recorded at the Honolulu International Airport, contributing to the wettest August on record in the city.[21] Some coffee and macadamia nut trees were damaged.[22]

Tropical Depression Six-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 1 – August 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 30 mph (45 km/h) (1-min); 1008 mbar (hPa) |

Operationally, an area of disturbed weather was thought to have coalesced into a tropical depression at 09:00 UTC on July 29 while located well southwest of the Baja California Peninsula. The depression was only expected to intensify slightly before entering cooler waters and interacting with outflow from nearby Hurricane Darby.[23] By late that evening, however, its presentation on satellite imagery more resembled a trough, and the NHC discontinued advisories.[24] In post-season analysis, the organization determined that the depression did not form until 06:00 UTC on August 1 but lasted 24 hours.[25]

Tropical Storm Estelle

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 19 – August 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 989 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave interacted with a disturbance embedded in the ITCZ in mid-August, leading to the designation of a tropical depression at 06:00 UTC on August 19 while located 1,440 mi (2,320 km) east-southeast of Hilo, Hawaii. The cyclone moved west-northwest following formation, steered around a subtropical ridge. It intensified into Tropical Storm Estelle at 06:00 UTC on August 20 and attained peak winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) at 12:00 UTC the next morning as it crossed into the central Pacific.[26] Thereafter, increasing wind shear caused Estelle to a steady weakening trend. At 00:00 UTC on August 23, the cyclone decelerated to a tropical depression while turning west-southwest, and at 18:00 UTC the following day, it further degenerated into a remnant low. The post-tropical cyclone continued on a west-southwest trajectory prior to dissipating south-southeast of the Big Island at 00:00 UTC on August 26.[18]

Hurricane Frank

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 23 – August 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); 979 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave, the remnants of Tropical Storm Earl in the Atlantic, crossed into the eastern Pacific in mid-August and steadily organized to become a tropical depression at 06:00 UTC on August 23 well south of the coastline of Mexico. The depression intensified into Tropical Storm Frank six hours later as banding features and central convection increased. Steered northwest within a favorable environment, the cyclone rapidly intensified into a Category 1 hurricane by 18:00 UTC and ultimately attained peak winds of 85 mph (137 km/h) twelve hours later. Frank steadily weakened thereafter as it entered cooler ocean temperatures, degenerating into a remnant low at 06:00 UTC on August 26. The remnant low drifted southwest before diffusing into a trough well south of the Baja California Peninsula the following day.[27]

Tropical Depression Nine-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 23 – August 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1005 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave crossed Central America on August 15, only slowing organizing into a tropical depression at 18:00 UTC on August 23 while located about 920 mi (1,480 km) west-southwest of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico. Steered north-northwest and eventually west, the cyclone failed to intensify further into a tropical storm amid cool sea surface temperatures and southerly wind shear, and it instead degenerated into a remnant low at 18:00 UTC on August 26. The post-tropical cyclone turned west-southwest before dissipating about 1,095 mi (1,762 km) east of Hilo, Hawaii early on August 28.[28]

Tropical Storm Georgette

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 26 – August 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 995 mbar (hPa) |

A westward-moving tropical wave entered the eastern Pacific in late August, acquiring sufficient organization to be declared a tropical depression at 12:00 UTC on August 26 about 605 miles (974 km) south-southeast of the Baja California Peninsula. The depression intensified into Tropical Storm Georgette six hours later as its satellite presentation improved, and it reached peak winds of 65 mph (105 km/h) at 12:00 UTC on August 27. Increasingly hostile upper-level winds began to impinge on the west-northwest-moving tropical cyclone shortly thereafter, ultimately causing it to degenerate into a remnant low by 18:00 UTC on August 30. The post-tropical cyclone continued its forward course until dissipating early on September 3.[29]

Hurricane Howard

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 30 – September 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min); 943 mbar (hPa) |

A westward-moving tropical wave from Africa entered the eastern Pacific in late August, organizing into a tropical depression at 12:00 UTC on August 30 south of the coastline of Mexico. The depression intensified into Tropical Storm Howard twelve hours later and further developed into a hurricane at 06:00 UTC on September 1. On its northwest track, a favorable environment regime prompted the cyclone to begin a period of rapid intensification, and it attained its peak as a Category 4 hurricane with winds of 140 mph (230 km/h) at 12:00 UTC on September 2. Cooler ocean temperatures led to a steady weakening trend thereafter, and Howard degenerated into a remnant low at 18:00 UTC on September 5. The low turned southwest before dissipating over open waters on September 10.[30]

Although the storm remained offshore, the outer bands of the storm produced significant flooding across the Baja California peninsula,[31] which damaged agricultural land and at least 393 homes.[32] Swells reached 18 ft (5.5 m) along the Baja California coastline and 12 ft (3.7 m) along the California coastline; about 1,000 lifeguard rescues took place in California due to the waves.[33][34] Moisture from the storm enhanced rainfall in parts of Arizona, leading to minor accumulations.[35]

Hurricane Isis

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 8 – September 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min); 987 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave, possibly responsible for the formation of Hurricane Frances in the Atlantic, entered the eastern Pacific in early September, gaining sufficient organization to be declared a tropical depression at 06:00 UTC on September 8 about 530 miles (850 km) south of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico. The system tracked west, intensifying into Tropical Storm Isis twelve hours after being designated, but weakening back to a tropical depression early on September 10, amid persistent wind shear. Upper-level winds decreased by September 12, allowing Isis to regain tropical storm intensity by 00:00 UTC, and eventually peak as a Category 1 hurricane with winds of 75 mph (121 km/h), at 12:00 UTC on September 15. After conducting a clockwise loop, the hurricane entered cooler waters and began to weaken; it degenerated into a remnant low at 18:00 UTC on the next day. The low drifted southwest and then west, before dissipating well east of Hawaii on September 21.[36]

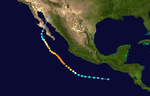

Hurricane Javier

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 10 – September 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min); 930 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave entered the eastern Pacific in early September, organizing into a tropical depression at 18:00 UTC on September 10 south of the Gulf of Tehuantepec. Under light shear, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Javier at 12:00 UTC the next morning and into a hurricane at 18:00 UTC on September 12. The cyclone soon began a period of rapid intensification as it alternated on a west-northwest to northwest course, ultimately peaking as a Category 4 hurricane with winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) at 00:00 UTC on September 14 as a distinct pinhole eye became evident on satellite imagery. Cooler waters, strong southwesterly shear, and an eyewall replacement cycle all weakened Javier thereafter; it fell to tropical depression intensity early on September 19 before crossing Baja California and degenerated into a remnant low at 18:00 UTC that day over the Gulf of California. The low crossed the state of Sonora before dissipating over mountainous terrain on September 20.[13]

As a tropical cyclone, Javier produced moderate rainfall peaking at 3.14 in (80 mm) in Bacanuchi, Mexico.[37] Three fishermen went missing offshore the coastline due to high surf.[38] As a post-tropical cyclone, the storm's remnant moisture overspread the Southwest United States, alleviating a multi-year drought.[39] Accumulations peaked at 7 in (180 mm) in Walnut Creek, Arizona, with lighter totals across the Four Corners and upper Midwest.[40] The remnants of Javier produced 2 in (51 mm) of rain in Wyoming, cementing its status as the wettest tropical cyclone in the reliable record there.[41]

Tropical Storm Kay

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 4 – October 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1004 mbar (hPa) |

An area of disturbed weather developed within the ITCZ well southwest of mainland Mexico, coalescing into a tropical depression at 18:00 UTC on October 4. The depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Kay twelve hours later, and it attained peak winds of 45 mph (72 km/h) at 12:00 UTC the next morning as suggested by satellite intensity estimates. Moderate northerly shear caused core convection to decrease as the system moved west-northwest, resulting in Kay degenerating into a remnant low at 12:00 UTC on October 6 over open ocean. The low-level swirl curved southwestward and dissipated the next day.[42]

Tropical Storm Lester

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 11 – October 13 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1000 mbar (hPa) |

By October 10, an area of disturbed weather was situated well to the southwest of the Gulf of Tehuantepec. Later that day, a surface low pressure system developed, and convection began to organize into slightly curved bands. The disturbance continued to in this manner, and at 1800 UTC on October 11, the low level circulation had become sufficiently organized to be designated as a tropical depression.[43] At the time, the depression consisted of a well-defined circulation, with some deep thunderstorm activity. Despite weak steering currents, the system started what was initially thought to be a westward drift,[44] though just a few hours later was found to be towards the northwest. A small cyclone, a burst of deep convection formed at around the same time, and was said could have produced tropical storm-force winds.[45]

Continuing its slow, northwestward track under the weal steering currents of a weak mid-level ridge to its north, and a broad cyclonic circulation to its southwest, it was upgraded to Tropical Storm Lester at 1800 UTC on October 12.[43] Originally, it was unclear whether the center of circulation would remain slightly offshore, or move inland.[46] Due to the presence of a weak upper-level anticyclone that was centered just east of the system, favorable atmospheric conditions for strengthening prevailed, and the storm reached its peak intensity with winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) about 6–12 hours after being upgraded to a tropical storm.[43] Early on October 13, radar imagery from Acapulco, Mexico indicated that Lester remained a small and well-organized cyclone as it passed just offshore. At the same time, light southwesterly wind shear began to develop.[47] The interaction with land, combined with influence from the low to the southwest, started to weaken the storm, and it was downgraded to a tropical depression at 1200 UTC on October 13. By later that day, reports from an Air Force Reserve Unit Hurricane Hunter Aircraft indicated that the cyclone had degenerated into a trough on the northeastern side of the larger low to the southwest.[43]

On October 12, in response to Lester, the Mexican government issued a tropical storm watch for the coast between Punta Maldonado to Zihuatanejo. It was upgraded to a warning later that day. It was extended to Lázaro Cárdenas on October 13. Later that day, the warning was lifted when Lester dissipated.[43] Lester brought rains to parts of Oaxaca and Guerrero, reaching 3 to 5 inches (76 to 127 mm). The highest 24-hour total peaked at 106.5 mm (4.19 in), recorded on October 12.[48] The storm capsized two ships, and washed two more ashore. The heavy rain caused mudslides, which buried one man in his home; he was later rescued by his family.[49] In and around the port of Acapulco, minor flooding was reported[49] and 42 trees toppled. Four landslides blocked four roads in Nayarit. A total of 13 families were evacuated in Rosamorada.[50]

Tropical Depression Sixteen-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 25 – October 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1004 mbar (hPa) |

On October 8, 2004, a tropical wave emerged from the west coast of Africa and progressed westward through the Atlantic Ocean. As is typical of disturbances in the late hurricane season, the wave maintained a relatively low latitude during its trek across the Atlantic. On October 18, the system emerged into the eastern Pacific Ocean. Convection developed along the wave axis, and an area of low pressure developed the next day, while situated south of Guatemala. It drifted westward uneventfully until October 23, when it became nearly stationary. Strong thunderstorms amplified and organized into banding features early on October 24. Dvorak classifications were issued on the weather feature, and over the following day it moved slowly towards the north. At 00:00 UTC on October 25, the system was designated Tropical Depression Sixteen-E about 320 mi (510 km) south-southeast of Baja California.[51]

The depression intensified slightly, and attained its peak winds of 35 mph (55 km/h) almost immediately after forming. As such, it never attained tropical storm status;[51] however, had it been upgraded, it would have been named Madeline.[52] The large cyclone moved towards the north along the western edge of the Mexican subtropical ridge.[51] Even shortly after the storm's classification, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) remarked that Sixteen-E would have little time to significantly strengthen, although noted the possibility for it to achieve minimal tropical storm status. At the time, the storm was being disrupted by wind shear, with most of its deep convective activity concentrated in the eastern half of the circulation.[53]

At around 20:00 UTC, an area of strong convection, including cold cloud tops, developed near the center of circulation. The burst of thunderstorms may have been related to an approaching trough. Tropical Depression Sixteen-E continued moving towards the coast of Mexico, and at 00:00 UTC on October 26, it reached its lowest barometric pressure of 1004 mbar (hPa; 29.65 inHg). It crossed the southwestern Gulf of California before moving ashore between Guasave and Topolobampo.[51] The deteriorating cyclone moved inland, and the last advisory was issued by the NHC on the storm shortly thereafter.[54] Although the storm dissipated at 18:00 UTC, its remnants persisted as they moved across northern Mexico. The system interacted with a weather front in the southwestern United States and triggered thunderstorms there.[51]

On October 25, a tropical storm warning was issued for the coastline of Mexico from El Roblito northward to Topolobampo. This advisory was discontinued the next day, and no additional tropical cyclone watches and warnings were posted. The storm produced areas of heavy rainfall.[51] At Culiacan, 179.9 mm (7.08 in) of precipitation fell in a 24-hour period; 59.6 mm (2.35 in) fell at Empalme.[55] Despite localized flooding, no damage or fatalities were reported. At the Culiacan airport, a wind gust to 81 mph (130 km/h) was reported. A possible tornado may have also touched down near there. Offshore, a ship—the Diamond Princess—recorded 33 mph (53 km/h) winds on two separate occasions during October 26, potentially suggesting that the storm was stronger than it was believed to be. The interaction between the depression's remnants and a frontal boundary over the southwestern United States produced strong thunderstorms and heavy precipitation in eastern New Mexico, western and central Texas, and much of Oklahoma.[51]

Other system

On August 14, the Japan Meteorological Agency had stated that Tropical Storm Malakas had briefly exited the West Pacific basin and entered the Central Pacific basin, as a weakening tropical depression.[56]

Storm names

The following list of names was used for named storms that formed in the North Pacific east of 140°W in 2004.[57] This is the same list used for the 1998 season.[58] No names were retired from this list by the World Meteorological Organization following the season, and it was used again for the 2010 season.[59]

|

|

For storms that form in the North Pacific between 140°W and the International Date Line, the names come from a series of four rotating lists. Names are used one after the other without regard to year, and when the bottom of one list is reached, the next named storm receives the name at the top of the next list.[57] No named storms formed within the region in 2004. Named storms in the table above that crossed into the area during the year are noted (*).[18]

Season effects

This is a table of all of the storms that formed in the 2004 Pacific hurricane season. It includes their name, duration, peak classification and intensities, areas affected, damage, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 2004 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agatha | May 22–24 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 997 | Revillagigedo Islands, Clarion Island, Southwestern Mexico | None | None | |||

| Two-E | July 2–3 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1007 | None | None | None | |||

| One-C | July 5 | Tropical depression | 30 (45) | 1007 | None | None | None | |||

| Blas | July 12–15 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 991 | Northwestern Mexico, Baja California Peninsula, Southwestern United States | None | None | |||

| Celia | July 19–25 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 981 | None | None | None | |||

| Darby | July 26 – August 1 | Category 3 hurricane | 120 (195) | 957 | None | Minimal | None | |||

| Six-E | August 1–2 | Tropical depression | 30 (45) | 1008 | None | None | None | |||

| Estelle | August 19–24 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 989 | None | None | None | |||

| Frank | August 23–26 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 979 | Baja California Peninsula | None | None | |||

| Nine-E | August 23–26 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1005 | None | None | None | |||

| Georgette | August 26–30 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 995 | None | None | None | |||

| Howard | August 30 – September 5 | Category 4 hurricane | 140 (220) | 943 | Baja California Peninsula, Western United States, California, Arizona | Minimal | None | |||

| Isis | September 8–16 | Category 1 hurricane | 75 (120) | 987 | None | None | None | |||

| Javier | September 10–19 | Category 4 hurricane | 150 (240) | 930 | Baja California Peninsula, Northwestern Mexico, Southwestern United States, Arizona, Texas | Minimal | 3 missing | |||

| Kay | October 4–6 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1004 | None | None | None | |||

| Lester | October 11–13 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1000 | Southwestern Mexico | None | None | |||

| Sixteen-E | October 25–26 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1004 | Baja California Peninsula, Northwestern Mexico, Southwestern United States, Texas, California | None | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 17 systems | May 22 – October 26 | 150 (240) | 930 | Minimal | None | |||||

See also

- List of Pacific hurricanes

- Pacific hurricane season

- Tropical cyclones in 2004

- 2004 Atlantic hurricane season

- 2004 Pacific typhoon season

- 2004 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2003–04, 2004–05

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2003–04, 2004–05

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2003–04, 2004–05

References

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". Central Pacific Hurricane Center. May 12, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- ^ a b Informe sobre el pronóstico de la temporada de ciclones del 2004 (Report) (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. January 2004. Archived from the original on April 14, 2005. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Informe sobre el Pronóstico de la Temporada de Ciclones del 2004 (Report) (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. May 2004. Archived from the original on April 14, 2005. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b NOAA Issues 2004 Experimental Eastern Pacific Hurricane Outlook (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 21, 2004. Archived from the original on 2016-12-09. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ a b Informe sobre el Pronóstico de la Temporada de Ciclones del 2004 (Report) (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. August 2004. Archived from the original on April 14, 2005. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ NOAA Expects Near Average Central Pacific Hurricane Season (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 17, 2004. Archived from the original on 2016-12-09. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ "Basin Archives: Northeast Pacific Ocean Historical Tropical Cyclone Statistics". Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- ^ Hurricane Specialist Unit (December 1, 2004). Tropical Weather Summary: November (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ a b Lixion A. Avila (June 2, 2004). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Agatha (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila; Stacy R. Stewart (July 1, 2004). Tropical Weather Summary: July (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ "Hurricane Celia". Earth Observatory, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. 23 July 2004. Retrieved August 1, 2022.

- ^ a b Jack L. Beven II (December 17, 2004). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Darby (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^ a b Lixion A. Avila (November 15, 2004). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Javier (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center (April 26, 2024). "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2023". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Archived from the original on May 29, 2024. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Hurricane Specialist Unit (August 2, 2005). "Eastern North Pacific Hurricane Season of 2004". National Hurricane Center. 137 (3). American Meteorological Society: 1026. Bibcode:2006MWRv..134.1026A. doi:10.1175/MWR3095.1.

- ^ a b Miles B. Lawrence (July 17, 2004). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Depression Two-E (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila (July 2, 2004). "Tropical Depression Two-E Discussion Number 2". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Nash, Andy; Craig, Tim; Matsuda, Roy; Powell, Jeffrey (February 2005). 2004 Tropical Cyclones Central North Pacific (PDF) (Report). Honolulu, Hawaii: Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ^ Richard J. Pasch (August 5, 2004). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Blas (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1–3. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (October 12, 2004). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Celia (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^ Excessive Rainfall from the Remnants of Darby (Report). National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Honolulu, Hawaii. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ Howard Dicus (August 5, 2004). "Rains flood some farmlands but most manage well". American City Business Journals. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart. Tropical Depression Six-E Discussion Number 1 (Report). July 29, 2004. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ James L. Franklin. Tropical Depression Six-E Discussion Number 4 (Report). July 29, 2004. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ James L. Franklin; Richard D. Knabb (November 16, 2004). Abbreviated Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Depression Six-E (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila (November 3, 2004). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Estelle (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 4. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ^ David P. Roberts; Miles B. Lawrence (November 19, 2004). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Frank (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ Richard J. Pasch (November 12, 2004). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Depression Nine-E (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (October 14, 2004). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Georgette (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ Jack L. Beven II (December 13, 2004). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Howard (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ Luciano Garcia Valenzuela (September 4, 2004). "Decretan alerta por "Howard"". El Siglo de Durango (in Spanish). Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ "Apoyaran Para Rehabilitar Viviendas" (in Spanish). Navajoa. September 9, 2004. Archived from the original on July 5, 2007. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Yi-Wyn Wen (September 13, 2004). "The Perfect Storms". Sports Illustrated Vault. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ Storm Event: California High Surf (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. 2004. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ Chuck George (September 3, 2004). "Rainy Start To Tucson's Labor Day Weekend". KOLD News. Archived from the original on January 3, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ James L. Franklin; David P. Roberts (November 17, 2004). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Isis (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ Huracán "Javier" del Oceano Pacifíco (PDF) (Report) (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. December 1, 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 18, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ "Huracán "Javier" acecha a la costa pacífica de México". Nacion Internacionales. September 15, 2004. Archived from the original on 2016-10-18. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ Weekly Weather and Crop Bulletin (Report). National Agricultural Statistics Service. September 21, 2004. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ David M. Roth. Hurricane Javier – September 18–21, 2004 (Report). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ David M. Roth. "Maximum Rainfall caused by Tropical Cyclones and their remnants per state (1950–2012)" (GIF). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ David P. Roberts; Miles B. Lawrence (November 20, 2004). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Kay (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Richard J. Pasch; David P. Roberts (2004-12-10). "Tropical Storm Lester Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-05-22.

- ^ Michelle Mainelli & Richard Pasch (2004-10-11). "Tropical Depression Fifteen-E Discussion Number 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ^ Stacy Stewart (2004-10-12). "Tropical Depression Fifteen-E Discussion Number 2". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ^ Richard Pasch (2004-10-12). "Tropical Storm Lester Discussion Number 5". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ^ Jack Beven (2004-10-13). "Tropical Storm Lester Discussion Number 7". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ^ Tropical storm "Lester" Pacific Ocean (PDF) (Report). SMN. 2004. Retrieved 2008-09-25.

- ^ a b Amado Ramirez (2004). "Raging storm 'Lester' to Guerrero". Noticieros Televisa.

- ^ "Cuatro derrumbes en carreteras de La Montaña y Centro, y 42 árboles caídos en Acapulco, daños por Lester". El Ser Perodico de Guerrero. October 14, 2004. Archived from the original on December 27, 2016. Retrieved December 26, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Stacy R. Stewart (November 18, 2004). "Tropical Depression Sixteen-E Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 22, 2015.

- ^ "Worldwide Tropical Cyclone Names". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ Forecaster Stewart (October 25, 2004). "Tropical Depression Sixteen-E Discussion Number 2". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ Forecaster Lawrence. "Tropical Depression Sixteen-E Discussion Number 4". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ "Aviso de la Depresión Tropical "16-E"" (in Spanish). cfe.gob.mx. October 26, 2004. Retrieved February 15, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Digital Typhoon: List of weather charts on August 14, 2004 (Sat)". Digital Typhoon. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- ^ a b National Hurricane Operations Plan (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: NOAA Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research. May 2004. p. 3-10–11. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

- ^ National Hurricane Operations Plan (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: NOAA Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research. May 1998. p. 3-8. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ^ National Hurricane Operations Plan (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: NOAA Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research. May 2010. p. 3-8. Retrieved January 30, 2024.