1963 Atlantic hurricane season

| 1963 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | June 1, 1963 |

| Last system dissipated | October 30, 1963 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Flora |

| • Maximum winds | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 933 mbar (hPa; 27.55 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 11 |

| Total storms | 10 |

| Hurricanes | 7 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 3 |

| Total fatalities | 7,214 |

| Total damage | $833.8 million (1963 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The 1963 Atlantic hurricane season was a slightly below average season in terms of tropical cyclone formation, with a total of ten nameable storms. Even so, it was also a notoriously deadly and destructive season. The season officially began on June 15, 1963, and lasted until November 15, 1963. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. The first system, an unnamed tropical storm, developed over the Bahamas on June 1.

In late July, Hurricane Arlene, developed between Cape Verde and the Lesser Antilles. The storm later impacted Bermuda, where strong winds resulted in about $300,000 (1963 USD) in damage. During the month of September, Tropical Storm Cindy caused wind damage and flooding in Texas, leaving three deaths and approximately $12.5 million in damage. Hurricane Edith passed through the Lesser Antilles and the eastern Greater Antilles, causing 10 deaths and about $43 million in damage, most of which occurred on Martinique.

The most significant and deadliest system of the season was Hurricane Flora, which peaked as a Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale. Drifting slowly and executing a cyclonic loop, Flora dropped very heavy rainfall in the Greater Antilles, including over 100 in (2,500 mm) in Cuba. Extreme flooding ensued, leaving behind at least 7,193 fatalities and about $773.4 million in damage. In October, Hurricane Ginny moved erratically offshore the Southeastern United States, though eventually, the extratropical remnants struck Nova Scotia. Ginny caused at least three deaths and $400,000 in damage in the United States alone. The final cyclone, Tropical Storm Helena, caused five deaths and over $500,000 in damage on Guadeloupe. Overall, the storms in this season caused at least 7,214 deaths and about $833.8 million in damage.

Season summary

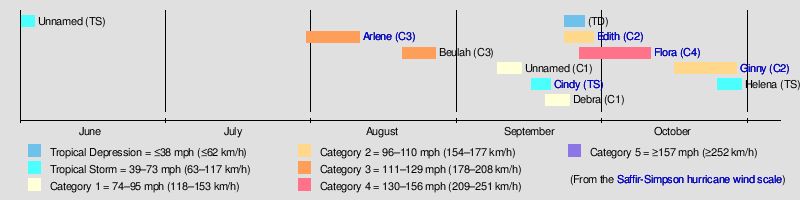

The 1963 hurricane season officially began on June 15 and ended on November 15.[1] It was an average season with ten tropical storms,[2] slightly above the 1950–2000 average of 9.6 named storms.[3] Seven of these reached hurricane status,[2] which is above the 1950–2000 average of 5.9.[3] Furthermore, three storms reached major hurricane status,[2] which is Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale.[4] Early in the season, activity was suppressed by an abnormally intense trough offshore the East Coast of the United States as well as strong westerly winds. Later, tropical cyclone formation occurred more often after a portion of the trough weakened and easterly flow increased across much of the Atlantic.[5]: 128 The tropical cyclones of the 1963 Atlantic hurricane season collectively caused at least 7,214 deaths and $833.8 million in damage.[5]: 128 [6]: 6

Tropical cyclogenesis began early, an unnamed tropical storm developing on June 1. However, activity ceased for nearly two months, before Arlene formed on July 31. Another system formed in August, Hurricane Beulah. September was much more active, with Cindy, Debra,[2] an unnumbered tropical depression.[7]: 270–271 Edith, and Flora all developing in that month. Flora was the most intense tropical cyclone of the season, peaking as a Category 4 hurricane with winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 933 mbar (27.55 inHg). There were two other system in October, Hurricane Ginny and Tropical Storm Helena; the latter dissipated on October 30.[2]

The season's activity was reflected with an above average accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 113.[3][4] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs. It is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 39 mph (63 km/h), which is the threshold for tropical storm strength.[8]

Systems

Unnamed tropical storm

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 1 – June 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 1000 mbar (hPa) |

Toward the end of May, a tropical disturbance moved northward from Panama toward the western Caribbean Sea. On May 31, a trough moved across eastern Cuba.[7]: 266 On June 1, a tropical depression developed over the western Bahamas.[2] Initially, the depression could have been a subtropical cyclone, due to an upper-level low located over the circulation.[7]: 277 The depression moved to the northeast and later to the north, strengthening into a tropical storm on June 2. A day later, the storm attained peak winds of 60 mph (95 km/h); on the same day, the storm made landfall just west of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. By June 4, the storm weakened to a tropical depression as it continued northwestward through Virginia, Maryland, and finally Pennsylvania,[2] where the depression degenerated into a trough.[7]: 270

The disturbance dropped heavy rainfall across Cuba, reaching 7.50 in (191 mm) in Santiago de Cuba.[7]: 266 The storm produced gusty winds along the eastern United States coast, from North Carolina through Maryland. Winds reached 40 mph (65 km/h) in Ocean City, Maryland and 39 mph (64 km/h) in Norfolk, Virginia. The latter city recorded 6.87 in (174 mm) of rainfall in a 24-hour period, setting a daily rainfall record for the location.[7]: 269 Heavy rainfall reached as far north as Washington, D.C.[9]: 427

Hurricane Arlene

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 31 – August 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min); 969 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into a tropical depression at 18:00 UTC on July 31 while located about halfway between the Lesser Antilles and Cape Verde.[2][7]: 169 It headed west, becoming Tropical Storm Arlene on August 2. Shortly thereafter, Arlene turned to the northeast and bypassed the Lesser Antilles. Around 00:00 UTC on August 5, Arlene weakened back to a tropical depression.[2] Based on ship data and reconnaissance aircraft flights being unable to locate a circulation, Arlene degenerated into a trough about 24 hours later.[7]: 173 Observations from ships indicated that the system became a tropical depression again early on August 7.[7]: 174 Several hours later, Arlene became a tropical storm again. While curving to the northeast on August 8, the cyclone intensified into a hurricane.[2]

Arlene intensified further on August 9 and was a strong Category 2 hurricane by the time it struck Bermuda with winds of 110 mph (175 km/h) at 15:30 UTC. Shortly thereafter, the system became a Category 3 hurricane and peaked with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h). Arlene weakened and lost tropical characteristics as it continued northeastward, becoming extratropical early on August 11 about 300 mi (485 km) southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland. The extratropical remnants turned east-southeastward and persisted for a few days, until dissipating just north of Madeira on August 14.[2] Several hurricane warnings and watches were issued for the Leeward Islands;[10] however, no damage was reported on any of the islands.[5]: 130 The storm had its greatest impact on Bermuda, where high winds and near-record rainfall of 6.05 in (154 mm) downed trees, power lines, and caused flooding.[5]: 130 [11][12] Damages across the island amounted to $300,000.[5]

Hurricane Beulah

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 20 – August 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min); 958 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa on August 11.[7]: 182 The system organized into a tropical depression early on August 20 about 540 mi (870 km) northeast of Cayenne, French Guiana. On August 21, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Beulah while moving to the northwest.[2] Later that day, the first reconnaissance aircraft flight into the storm observed winds of 52 mph (84 km/h).[5]: 130 Based on another reconnaissance flight on August 22 observing a barometric pressure of 977 mbar (28.9 inHg), Beulah intensified into a hurricane around 18:00 UTC.[7]: 186 The storm intensified into a Category 3 hurricane by early on August 24, at which time Beulah attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 120 mph (195 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 958 mbar (28.29 inHg).[2] Radar imagery depicted an elliptical eye with a diameter of 20 to 30 mi (32 to 48 km).[5]: 131

Early on August 25, Beulah weakened significantly due to unfavorable conditions caused by an anticyclone to its south,[5]: 131 falling to Category 1 intensity. After leveling off to sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) several hours later, Beulah maintained this intensity for the next few days.[2] Early on August 26, the hurricane turned northeastward under the influence of an upper-level trough offshore the East Coast of the United States.[5]: 131 At 00:00 UTC on August 28, the hurricane transitioned into an extratropical cyclone about 235 mi (380 km) east-southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland. The extratropical low eventually turned eastward towards western Europe. The remnants then moved erratically, striking Ireland, the United Kingdom twice, and France before entering the North Sea. On September 8, the remnants finally dissipated north of Jan Mayen.[2]

Unnamed hurricane

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 9 – September 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); 990 mbar (hPa) |

As early as September 8, ships north of Puerto Rico reported a weak circulation. Drifting northward,[5]: 131 the system developed tropical depression by 12:00 UTC on September 9, while situated about 355 mi (570 km) northeast of Turks and Caicos Islands.[2] The cyclone was subtropical in nature, fueled by both latent heat and instability from contrasting cool and warm air masses. While passing Bermuda later on September 10, sustained wind speeds of 25 mph (40 km/h) and decrease in barometric pressure were observed.[5]: 131 The system moved east-northeastward and strengthened into a tropical storm late on September 10. The cyclone intensified further and reached hurricane status early on September 12, peaking with maximum sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 990 mbar (29.23 inHg).[2] Around that time, the Freiburg observed winds of 78 mph (126 km/h).[5]: 131 Thereafter, the system weakened to a tropical storm about 24 hours later and accelerated to the northeast ahead of a cold front. Around 12:00 UTC on September 14,[2] the storm was absorbed by a large extratropical cyclone while located about 725 mi (1,167 km) north-northwest of Corvo Island in the Azores.[7]: 198

Tropical Storm Cindy

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 16 – September 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 996 mbar (hPa) |

In mid-September, a trough of low pressure was situated in the Gulf of Mexico.[5]: 131 The system developed into Tropical Storm Cindy at 12:00 UTC on September 16, while located about 210 mi (340 km) south of Cameron, Louisiana. Cindy strengthened while moving north-northwestward. Around that time, the storm attained its peak intensity with maximum winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 996 mbar (29.41 inHg). Around 14:00 UTC on September 17, Cindy made landfall near High Island, Texas, at that intensity. After landfall, Cindy weakened to a tropical depression within about 22 hours. Turning southwest, the depression dissipated near Alice, Texas, at 00:00 UTC on September 20.[2]

In southwestern Louisiana, over 15 in (380 mm) of rain fell in some areas. Rice crops were flooded, causing about $360,000 in damage. However, the precipitation was described as more beneficial than detrimental.[5]: 132 Along the coast, tides inundated roads leading to Cameron and Holly Beach.[13] A man drowned offshore Cameron while evacuating from an oil rig. The storm brought flooding to the southeastern Texas, particularly in and around Port Arthur. Two people drowned in the Port Acres area. Water entered 4,000 homes across Jefferson, Newton, and Orange counties.[5]: 132 In Oklahoma, flooding in Guthrie prompted 300 residents to flee their homes; water intruded into 25 businesses and 35 homes.[14] Overall, Cindy caused about $12.5 million in damage, of which $11.7 million stemmed from property damage.[5]: 132

Hurricane Debra

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 19 – September 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min); 999 mbar (hPa) |

On September 19, a westward moving tropical wave became a tropical depression about 900 mi (1,400 km) east of the southwesternmost islands of Cape Verde.[2][5]: 132 The depression moved northwestward and strengthened into Tropical Storm Debra early the next day. Despite the system's intensity at the time,[2] a reconnaissance aircraft flight observed a radar eye on September 20.[5]: 132 On the next day, Debra curved northward and intensified into a hurricane around 18:00 UTC. The cyclone peaked with maximum sustained winds of 75 mph (120 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 999 mbar (29.50 inHg). Debra soon began weakening and fell to tropical storm status late on September 22. The system continued weakening and dissipated late on September 24, while located about halfway between Bermuda and Flores Island in the Azores.[2]

Hurricane Edith

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 23 – September 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); 990 mbar (hPa) |

An Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) disturbance developed into a tropical depression while east of the Windward Islands on September 23.[15]: 1 The depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Edith early the next day. Several hours later, Edith intensified into a hurricane. Around 00:00 UTC on September 25, the cyclone became a Category 2 hurricane just north of Barbados and peaked with winds of 100 mph (155 km/h). Seven hours later, Edith struck Saint Lucia at the same intensity. The storm traversed the eastern Caribbean Sea and weakened to a tropical storm early on September 26. Edith then turned northwestward and briefly became a hurricane again, but weakened to a tropical storm before making landfall near La Romana, Dominican Republic, at 10:00 UTC the next day.[2] Interaction with land and an upper-level trough caused Edith to weaken considerably before it emerged into the Atlantic on September 28.[5]: 133 Several hours later, Edith struck Providenciales in the Turks and Caicos Islands as a tropical storm. The storm weakened to a tropical depression and became extratropical just east of the Bahamas on September 29.[2] The extratropical low was soon absorbed by an extratropical system developing offshore the East Coast of the United States.[7]: 219

In Martinique, a wind gust of 127 mph (204 km/h) was observed at Le Lamentin Airport; tides about 8 ft (2.4 m) above normal and heavy rainfall impacted the island.[16] Throughout the island, about 6,000 homes were demolished and 13,000 other were severely impacted.[15]: 1 Agriculture suffered significantly, with bananas and other food crops destroyed, while sugar cane experienced significant damage.[17] Winds up to 80 mph (130 km/h) caused significant damage on Dominica and strong winds on Saint Lucia ruined about half of the island's banana crop.[5]: 133 In Puerto Rico, the storm brought heavy rainfall to the southwest corner of the island and abnormally high tides to the south coast. Several beach front properties were badly damaged, particularly in the Salinas municipality.[18] Overall, Edith caused 10 deaths, all on Martinique, and approximately $46.6 million in damage.[5]: 128 and 133

Hurricane Flora

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 28 – October 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min); 933 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into a tropical depression well east of the Lesser Antilles at 12:00 UTC on September 28.[7]: 223 About 24 hours later, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Flora. The cyclone intensified into a Category 1 hurricane early on September 29 and became a Category 2 hurricane before striking Tobago several hours later. Flora continued west-northwestward into the Caribbean and intensified into a Category 3 hurricane early on October 2 and became a Category 4 about 24 hours later. At 18:00 UTC on October 3, Flora peaked with winds of 150 mph (240 km/h). Early the next day, the hurricane made landfall in southwestern Haiti at the same intensity. Flora re-emerged into the Caribbean several hours later as a Category 3 hurricane. Late on October 4, the cyclone made landfall near San Antonio del Sur, Cuba, with winds of 120 mph (195 km/h). A ridge to the north caused Flora to stall and move erratically over eastern Cuba for four days. Flora weakened slowly over land, falling to a Category 1 hurricane on October 5, but re-strengthened into a Category 2 after briefly emerging into the Gulf of Guacanayabo. Flora weakened to a tropical storm late on October 7, about 24 hours before emerging into the Atlantic. However, Flora quickly re-strengthened into a Category 2 hurricane and pass through the southeastern Bahamas early on October 9. Thereafter, Flora continued northeastward and gradually weakened, falling to Category 1 intensity on October 11. Flora gradually lost convection and became extratropical on October 12 while located 270 mi (430 km) east-southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland.[2] The extratropical remnants continued north-northeastward until a larger extratropical cyclone absorbed it offshore Greenland on October 17.[7]: 239

In Trinidad and Tobago, abnormally high tides capsized six ships in Scarborough harbor,[19] while strong winds caused severe effects to coconut, banana, and cocoa plantations, with 50% of the coconut trees destroyed and 11% severely damaged. About 2,750 houses were destroyed, while 3,500 others were impacted. The hurricane killed 24 people and resulted in $30.1 million damage.[20]: 9 Six additional drowning fatalities occurred in Grenada. The slow movement of the storm resulted in record rainfall totals for the Greater Antilles. In Dominican Republic, over 3,800 sq mi (9,800 km2) of land was flooded. Bridges and roads were significantly damaged, with many roads left unpassable for several months. The hurricane caused about $60 million in damage and over 400 deaths.[5]: 134 In Haiti, flash floods washed out large sections of several towns, while mudslides buried some entire cities.[21]: 4 In most areas, crops were entirely destroyed.[5]: 134 Additionally, the combination of rough waves and strong winds destroyed three entire communities.[21] About 3,500 people were confirmed dead and damage ranged from $125 million to $180 million.[5]: 134 In Cuba, the storm dropped 100.39 in (2,550 mm) of rainfall at Santiago de Cuba.[22] Nearly all crops in southeastern Cuba were affected by strong winds and flooding. Many citizens were left stranded at the tops of their houses. Several entire houses were swept away by the flooding, and many roads and bridges were destroyed, resulting in major disruptions to communications.[23] Throughout the country, the hurricane destroyed as many as 30,000 dwellings.[6]: 6 Flora left at least 1,750 fatalities and $500 million in damage in Cuba.[5]: 135 [6]: 6 In Jamaica, the storm produced up to 60 in (1,500 mm) of precipitation at Spring Hill.[5]: 136 Flora was attributed to 11 deaths and about $11.9 million in damage on the island.[5]: 135 In the Bahamas, the storm left damage to crops, property, and roads that exceeded $1.5 million in damage, while one person drowned.[5]: 136 Overall, Hurricane Flora caused at least 7,193 deaths and over $783.4 million in damage.[5]: 135 [6]: 6

Hurricane Ginny

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 17 – October 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min); 948 mbar (hPa) |

Late on October 17,[2] a tropical depression formed near Turks and Caicos from the interaction of a trough and a tropical wave, although the system was not very tropical due to cold air.[5]: 136 [24]: 32 The depression intensified into Tropical Storm Ginny early on October 19. The next day, Ginny attained hurricane status,[2] and approached North Carolina before looping to the southwest due to a ridge over New England. By October 22, Ginny crossed the Gulf Stream and intensified, developing an eye.[5]: 136 [24]: 32 Ahead of an advancing trough,[25] Ginny turned sharply northward and later northeastward, paralleling the coast of the Southeastern United States. For eight days, the storm was within 250 mi (400 km) of the United States coastline. Moving farther offshore, Ginny gradually intensified and peaked with maximum sustained winds of 110 mph (175 km/h) late on October 28. Later that day, Ginny made landfall in Yarmouth County, Nova Scotia, shortly before becoming extratropical. Its remnants dissipated on October 30 over the Gulf of Saint Lawrence.[2]

Early in its existence, Ginny dropped heavy rainfall across the Dominican Republic and the Bahamas.[11] In Florida and Georgia, Ginny produced above normal tides that caused minor damage and beach erosion.[5]: 137 Rainfall was beneficial in South Carolina,[26] and in North Carolina, high tides caused minor flooding and destroyed one house.[27] In Massachusetts, wind gusts reached 76 mph (122 km/h) in Nantucket,[5]: 137 and 1,000 homes lost power in Chatham.[28] Ginny was the latest hurricane on record to affect Maine during a calendar year.[29]: 14 During its passage, the storm brought an influx of cold air that produced up to 4 ft (1.2 m) of snow in northern Maine, killing two people. Offshore, many boats were damaged or ripped from their moorings; one person died from a heart attack while trying to rescue his boat.[28] Damage from Ginny in the United States was estimated at $400,000.[5]: 138 In Canada, high winds downed trees and caused power outages, leaving the entirety of Prince Edward Island without power.[30]

Tropical Storm Helena

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 25 – October 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1002 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave accompanied by a large area of convection moved westward in late October.[5]: 138 On October 25, the wave spawned a tropical depression,[2] based on ship and reconnaissance flights reports of southwest winds and heavy rainfall. Although poorly defined,[5]: 138 the system gradually intensified and became Tropical Storm Helena. Late on October 26, Helena entered the Caribbean after passing between Dominica and Guadeloupe. The storm reached peak winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) on October 27. Its slow, erratic movement and failure to intensify further was due to a weak trough across the region. Early on October 28, Helena struck Antigua at the same intensity.[2] Around this time, the storm developed an intense rainband that produced winds of 58 mph (93 km/h), as measured by reconnaissance aircraft between Dominica and Guadeloupe.[5]: 138 However, Helena re-emerged into the Atlantic and weakened to a tropical depression on October 29 and dissipated on the following day.[2]

The threat of Helena prompted the San Juan Weather Bureau to issue a hurricane watch and later gale warnings for portions of the Lesser Antilles.[31] On the Guadeloupe, the storm left 500 people homeless, killed 5 people, and seriously injured 14 others. Several boats were heavily damaged or sank. Damage was estimated at $500,000.[5]: 138

Other system

A tropical wave or trough of low-pressure developed into a tropical depression over the Bay of Campeche on September 23. The depression remained nearly stationary due to a frontal boundary over the northern Gulf of Mexico. On September 26, the depression struck the west coast of the Yucatán Peninsula and re-emerged into the Bay of Campeche on the following day. Ships near the area reported barometric pressures of less than 1,005 mbar (29.7 inHg) but not gale-force winds. It is unknown if the depression remained a tropical cyclone beyond September 27, though it may have become a subtropical cyclone on September 28. The remnants of the depression became extratropical and moved rapidly northeastward, crossing Florida on September 29 and then dissipating offshore the Northeastern United States by October 1.[7]: 270 and 271

Storm names

The following list of names was used for named storms (tropical storms and hurricanes) that formed in the North Atlantic in 1963.[1] Storms were named Ginny and Helena for the first (and last) time in 1963.

|

|

Retirement

The name Flora was later retired. The names Ginny and Helena were also removed from the naming list. They were replaced with Fern, Ginger and Heidi for the 1967 season.[32][33]

Season effects

This is a table of all of the storms that formed in the 1963 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their name, duration, peak classification and intensities, areas affected, damage, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 1963 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unnamed | June 1–4 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 1000 | The Bahamas, North Carolina, Mid-Atlantic | Unknown | None | |||

| Arlene | July 31 – August 11 | Category 3 hurricane | 115 (185) | 969 | Lesser Antilles, Bermuda | $300,000 | None | |||

| Beulah | August 20–27 | Category 3 hurricane | 120 (195) | 958 | British Isles, France | None | None | |||

| Unnamed | September 9–14 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (140) | 990 | Bermuda | None | None | |||

| Cindy | September 16 – 20 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 996 | Texas, Louisiana | $12.5 million | 3 | |||

| Debra | September 19–24 | Category 1 hurricane | 75 (120) | 999 | None | None | None | |||

| Depression | September 23–27 | Tropical depression | Unknown | 1005 | Mexico | None | None | |||

| Edith | September 23–29 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (155) | 990 | Lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, Turks and Caicos Islands, Bahamas | $46.6 million | 10 | |||

| Flora | September 28 – October 11 | Category 4 hurricane | 150 (240) | 933 | Lesser Antilles, Leeward Antilles, Venezuela, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, Jamaica, Cuba, Bahamas, Turks and Caicos Islands, Bermuda, Atlantic Canada | $773.4 million | 7,193 | |||

| Ginny | October 17–29 | Category 2 hurricane | 110 (175) | 948 | Hispaniola, Turks and Caicos Islands, Bahamas, East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Canada | $500,000 | 3 | |||

| Helena | October 25–30 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1002 | Lesser Antilles | $500,000 | 5 | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 11 systems | June 1 – October 30 | 150 (240) | 933 | $833.8 million | 7,214 | |||||

See also

- 1963 Pacific hurricane season

- 1963 Pacific typhoon season

- 1963 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 1962–63 1963–64

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 1962–63 1963–64

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 1962–63 1963–64

References

- ^ a b "21 Stormy Ladies". The Age. Washington, D.C. The Associated Press and Reuters. June 6, 1963. p. 3. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved December 24, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Landsea, Chris (April 2022). "The revised Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT2) - Chris Landsea – April 2022" (PDF). Hurricane Research Division – NOAA/AOML. Miami: Hurricane Research Division – via Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory.

- ^ a b c Philip J. Klotzbach; William M. Gray (December 8, 2006). Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2007 (Report). Boulder, Colorado: Colorado State University. Archived from the original on 18 December 2006. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ^ a b Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. March 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al Gordon E. Dunn (March 1964). "The Hurricane Season of 1963" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 92 (3). Miami, Florida: United States Weather Bureau: 128–138. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1964)092<0128:thso>2.3.co;2. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Louis A. Pérez (October 1, 2014). Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution. New York City, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199301447. Retrieved November 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Christopher W. Landsea; Sandy Delgado (2019). "1963 Atlantic Hurricane Database Reanalysis" (PDF). Miami, Florida: Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ David Levinson (August 20, 2008). 2005 Atlantic Ocean Tropical Cyclones. National Climatic Data Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on December 1, 2005. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ^ Robert K. Dickson (September 1963). "The Weather and Circulation of June 1963". Monthly Weather Review. 91 (9). United States Weather Bureau: 468–473. Bibcode:1963MWRv...91..468D. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1963)091<0468:TWACOJ>2.3.CO;2. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Walter R. Davis (August 4, 1963). San Juan Weather Bureau Bulletin for Press, Radio, and Television 9 PM AST August 3, 1963 (Report). San Juan, Puerto Rico: United States Weather Bureau. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ^ a b Roth, David M. (January 3, 2023). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Arlene moves out to sea after hitting Bermuda". The Bend Bulletin. United Press International. August 10, 1963. p. 3. Retrieved May 3, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ E. J. Saltsman (October 16, 1963). Final report – Hurricane "Cindy", September 16–20, 1963. Weather Bureau Office, New Orleans, Louisiana (Report). New Orleans, Louisiana: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; National Hurricane Center. p. 3. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ^ Stanley G. Holbrok (September 26, 1963). Tropical Cyclone Reports. Weather Bureau Office, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma (Report). Oklahoma City, Oklahoma: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ^ a b Hurricane Edith, September 23-28, 1963, preliminary report with advisories and bulletins issued (PDF) (Report). United States Weather Bureau. December 2, 1963. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ M. Perrusset (October 2, 1963). Martinique (Report). Fort-de-France: United States Weather Bureau. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- ^ M. Perrusset (October 2, 1963). "Observations Des Stations Meteorologiques" (in French). Fort-de-France: United States Weather Bureau. Service Météorologique du groupe Antilles-Guyane. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- ^ The Affects of Hurricane "Edith" to Puerto Rico and Virgin Islands September 26-27, 1963. United States Weather Bureau (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ John D. Lee (1963). Trinidad and Tobago Effects (Report). Trinidad and Tobago Meteorological Service. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- ^ C. B. Daniel; R. Maharaj; G. De Souza (2002). Tropical Cyclones Affecting Trinidad and Tobago, 1725 to 2000 (PDF) (Report). Trinidad and Tobago Meteorological Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 23, 2005. Retrieved November 28, 2006.

- ^ a b Ralph L. Higgins (1963). Hurricane Flora Subsequent Report to the Dominican Republic and Haiti (Report). San Juan, Puerto Rico: Weather Bureau Office San Juan, Puerto Rico. Retrieved November 27, 2015.

- ^ Lluvias intensas observadas y grandes inundaciones reportadas (Report) (in Spanish). Instituto Nacional de Recursos Hidráulicos. 2003. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved February 10, 2007.

- ^ José Fernández Partagás (October 10, 1963). Information from Cuba (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 29, 2006.

- ^ a b Lewis J. Allison; Harold P. Thompson (June 1966). TIROS VII Infrared Radiation Coverage of the 1963 Atlantic Hurricane Season With Supporting Television and Conventional Meteorological Data (PDF) (Report). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2013. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ P.L. Moore (October 28, 1963). Ginny Advisory Number 31 (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Nathan Kronberg (October 30, 1963). Preliminary Report on Hurricane Ginny in South Carolina (GIF). Columbia, South Carolina, Weather Bureau Air Station (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Preliminary Report on Hurricane Ginny October 19 to 27 1963. Wilmington, North Carolina, Weather Bureau Office (Report). National Hurricane Center. October 28, 1963. Retrieved 2011-10-17.

- ^ a b Robert E. Lautzenhaiser (November 18, 1963). "Tropical Cyclone Reports — Hurricane Ginny" (GIF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Wayne Cotterly (1996). "Hurricanes and Tropical Storms; Their Impact on Maine and Androscoggin County" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 1, 2016. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ "1963-Ginny". Environment Canada. September 14, 2010. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Harry M. Hoose (November 1, 1963). Tropical Storm Helena, October 25-29, 1963 (GIF) (Report). San Juan, Puerto Rico, Weather Bureau Office. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Padgett, Gary (November 30, 2007). Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary August 2007 (Report). Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ 1967 National Hurricane Plan (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: Interdepartmental Committee for Meteorological Services. May 1967. p. 61. Retrieved February 21, 2024.