Hungary in World War II

During World War II, the Kingdom of Hungary was a member of the Axis powers.[1] In the 1930s, the Kingdom of Hungary relied on increased trade with Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany to pull itself out of the Great Depression. Hungarian politics and foreign policy had become more stridently nationalistic by 1938, and Hungary adopted an irredentist policy similar to Germany's, attempting to incorporate ethnic Hungarian areas in neighboring countries into Hungary. Hungary benefited territorially from its relationship with the Axis. Settlements were negotiated regarding territorial disputes with the Czechoslovak Republic, the Slovak Republic, and the Kingdom of Romania. On November 20, 1940, Hungary became the fourth member to join the Axis powers when it signed the Tripartite Pact.[2] The following year, Hungarian forces participated in the invasion of Yugoslavia and the invasion of the Soviet Union. Their participation was noted by German observers for its particular cruelty, with occupied peoples subjected to arbitrary violence. Hungarian volunteers were sometimes referred to as engaging in "murder tourism."[3]

After two years of war against the Soviet Union, Prime Minister Miklós Kállay began peace negotiations with the United States and the United Kingdom in autumn of 1943.[4] Berlin was already suspicious of the Kállay government, and in September 1943, the German General Staff prepared a project to invade and occupy Hungary. In March 1944, German forces occupied Hungary. When Soviet forces began threatening Hungary, an armistice was signed between Hungary and the USSR by Regent Miklós Horthy. Soon afterward, Horthy's son was kidnapped by German commandos and Horthy was forced to revoke the armistice. The Regent was then deposed from power, while Hungarian fascist leader Ferenc Szálasi established a new government, with German backing. In 1945, Hungarian and German forces in Hungary were defeated by advancing Soviet armies.[5]

Approximately 300,000 Hungarian soldiers and more than 600,000 civilians died during World War II, including between 450,000 and 606,000 Jews[6] and 28,000 Roma.[7] Many cities were damaged, most notably the capital Budapest. Most Jews in Hungary were protected from deportation to German extermination camps for the first few years of the war, although they were subject to a prolonged period of oppression by anti-Jewish laws that imposed limits on their participation in public and economic life.[8] From the start of the German occupation of Hungary in 1944, Jews and Roma were deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp. Hungary's borders were returned to their pre-1938 lines after its surrender.

Movement to the right

In Hungary, the joint effect of the Great Depression and the Treaty of Trianon resulted in shifting the political mood of the country towards the right. In 1932, the regent Miklós Horthy appointed a new prime minister, Gyula Gömbös. Gömbös was identified with the Hungarian National Defence Association (Magyar Országos Véderő Egylet, or MOVE). He led Hungarian international policy towards closer cooperation with Germany, and started an effort to assimilate minorities in Hungary. Gömbös signed a trade agreement with Germany (21 February 1934)[9] that led to fast expansion of the economy, drawing Hungary out of the Great Depression but making the country dependent on the German economy for both raw materials and export revenues.

Gömbös advocated a number of social reforms, one-party government[citation needed], revision of the Treaty of Trianon, and Hungary's withdrawal from the League of Nations. Although he assembled a strong political machine, his efforts to achieve his vision and reforms were frustrated by a parliament composed mostly of István Bethlen's supporters and by Hungary's creditors, who forced Gömbös to follow conventional policies in dealing with the economic and financial crisis. The result of the 1935 elections gave Gömbös more solid support in parliament. He succeeded in gaining control of the ministries of finance, industry, and defense and in replacing several key military officers with his supporters. In October 1936, he died due to kidney problems without realizing his goals.

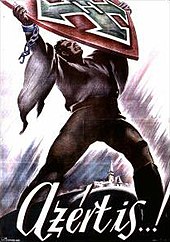

Hungary used its relationship with Germany to attempt to revise the Treaty of Trianon. In 1938, Hungary openly repudiated the treaty's restrictions on its armed forces. Adolf Hitler gave promises to return lost territories and threats of military intervention and economic pressure to encourage the Hungarian Government to support the policies and goals of Nazi Germany. In 1935, a Hungarian fascist party, the Arrow Cross Party, led by Ferenc Szálasi, was founded. Gömbös' successor, Kálmán Darányi, attempted to appease both Nazis and Hungarian antisemites by passing the First Jewish Law, which set quotas limiting Jews to 20% of positions in several professions. The law satisfied neither the Nazis nor Hungary's own radicals, and when Darányi resigned in May 1938 Béla Imrédy was appointed prime minister.

Imrédy's attempts to improve Hungary's diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom initially made him very unpopular with Germany and Italy. Aware of Germany's Anschluss with Austria in March, he realized that he could not afford to alienate Germany and Italy on a long-term basis: in the autumn of 1938 his foreign policy became very much pro-German and pro-Italian.[1] Intent on amassing a powerbase in Hungarian right wing politics, Imrédy started to suppress political rivals, so the increasingly influential Arrow Cross Party was harassed, and eventually banned by Imrédy's administration. As Imrédy drifted further to the right, he proposed that the government be reorganized along totalitarian lines and drafted a harsher Second Jewish Law. Imrédy's political opponents, however, forced his resignation in February 1939 by presenting documents showing that his grandfather was a Jew. Nevertheless, the new government of Count Pál Teleki approved the Second Jewish Law, which cut the quotas on Jews permitted in the professions and in business. Furthermore, the new law defined Jews by race instead of just religion, thus altering the status of those who had formerly converted from Judaism to Christianity.

Territorial expansion

Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy sought to peacefully enforce the claims of Hungarians on territories Hungary had lost with the signing of the 1920 Treaty of Trianon. Two significant territorial awards were made. These awards were known as the First Vienna Award and the Second Vienna Award.

In October 1938, the Munich Agreement caused the dissolution of the Czechoslovak Republic and the creation of the Czecho-Slovak Republic (also known as the "Second Czechoslovak Republic"). Some autonomy was granted to Slovakia and to Carpathian Ruthenia in the new republic. On 5 October, about 500 members of the Hungarian Ragged Guard infiltrated Slovakia and Ruthenia as "guerrillas". On 9 October, the Kingdom of Hungary started talks with the Czecho-Slovak Republic over Magyar-populated regions of southern Slovakia and southern Ruthenia. On 11 October, the Hungarian guards were defeated by Czecho-Slovak troops at Berehovo and Borzsava in Ruthenia. The Hungarians suffered approximately 350 casualties and, by 29 October, the talks were deadlocked.[10]

First Vienna Award

On 2 November 1938, the First Vienna Award transferred to Hungary parts of southern Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia from Czechoslovakia, an area amounting to 11,927 km2 and a population of 869,299 (86.5% of which were Hungarians[11]). Between 5 and 10 November, Hungarian armed forces occupied the newly transferred territories.[10]

Occupation of Carpatho-Ukraine

In March 1939, the Czecho-Slovak Republic was dissolved, Germany invaded it, and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was established. On 14 March, Slovakia declared itself to be an independent state. On 15 March, Carpatho-Ukraine declared itself to be an independent state. Hungary rejected the independence of Carpatho-Ukraine and, between 14 and 18 March, Hungarian armed forces occupied the rest of Carpathian Ruthenia and ousted the government of Avgustyn Voloshyn. By contrast, Hungary recognized the German puppet state of Slovakia led by the Clerical Fascist Jozef Tiso[12] but on 23 March 1939, Hungarian attacks on Slovakia on the east claiming a border dispute, led to a localized armed conflict between the two countries. The Slovak–Hungarian War, also known as the "Little War", ended with Hungary gaining the easternmost strip of Slovakia, 1697 km2.

Second Vienna Award

In September 1940, with troops massing on both sides of the Hungarian-Romanian border, war was averted by the Second Vienna Award. This award transferred to Hungary the northern half of Transylvania, with a total area of 43,492 km2 and a total population of 2,578,100. Regarding demographics, the Romanian census from 1930 counted 38% Hungarians and 49% Romanians, while the Hungarian census from 1941 counted 53.5% Hungarians and 39.1% Romanians.[13] While according to the Romanian estimations in 1940 prior to the Second Vienna Award, about 1,300,000 people or 50% of the population was Romanian and according to the Hungarian estimations in 1940 shortly following the Second Vienna Award, about 1,150,000 people or 48% of the population was Romanian.[14] The establishment of Hungarian rule met sometimes insurgency, most notable cases are the Ip and Treznea incidents in Northern Transylvania.

Occupation and annexation of Yugoslav territories

After invading Yugoslavia on 11 April 1941, Hungary annexed sections of Baranja, Bačka, Međimurje, and Prekmurje.[15] The returned territories – 11,417 km2 – had a population of 1,025,508 which comprised 36.6% Hungarians, 19% Germans, 16% Serbs and 28.4% others.[16] Nearly one year later the Novi Sad raid was conducted initially targeting Partisan resistance,[17] while between 1944–45, it was followed by the purges by the Partisan movement.

Administration of Greater Hungary

Following the two Vienna awards, a number of counties that had been lost in whole or part by the Treaty of Trianon were restored to Hungary. As a result, some previously county of temporary united administration – in Hungarian közigazgatásilag egyelőre egyesített vármegye (k.e.e. vm.) – were de-merged and restored to their pre-1920 boundaries.

The region of Sub-Carpathia was planned to be granted a special autonomous status with the intention that (eventually) it would be self-governed by the Ruthenian minority. This was prepared and billed in the Hungarian Parliament, but in the end, after the outbreak of the Second World War it never passed through.[18] However, in the corresponding territory the Governorate of Subcarpathia was formed which was divided into three, the administrative branch offices of Ung (Hungarian: Ungi közigazgatási kirendeltség), Bereg (Hungarian: Beregi közigazgatási kirendeltség) and Máramaros (Hungarian: Máramarosi közigazgatási kirendeltség), having Hungarian and Rusyn language as official languages.

Military campaigns

Invasion of Yugoslavia

On 20 November 1940, under pressure from Germany, Hungarian prime minister Pál Teleki signed the Tripartite Pact. In December 1940 Teleki also signed an ephemeral Treaty of Eternal Friendship with the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, which was led by a regent, Prince Paul, who was also under German pressure.

On 25 March 1941, Prince Paul signed the Tripartite Pact on behalf of Yugoslavia. Two days later, a Yugoslavian coup d'état removed Prince Paul, replaced him with pro-British King Peter, and threatened the success of the planned German invasion of the Soviet Union.

Hitler asked the Hungarians to support his invasion of Yugoslavia. He promised to return some territory to Hungary in exchange for military cooperation. On 3 April 1941, unable to prevent Hungary's participation in the war alongside Germany, Teleki committed suicide. The right-wing radical László Bárdossy succeeded him as prime minister.

Three days after Teleki's death, the Luftwaffe bombed Belgrade without warning. The German army invaded Yugoslavia and quickly crushed Yugoslavian armed resistance. Horthy dispatched the Hungarian Third Army to occupy Vojvodina.

Invasion of the Soviet Union

Hungary did not immediately participate in the invasion of the Soviet Union. The Axis invasion began on 22 June 1941, but Hitler did not directly ask for Hungarian assistance. Nonetheless, many Hungarian officials argued for participation in the war in order to encourage Hitler not to favour Romania in the event of border revisions in Transylvania. On 26 June 1941, unidentified airplanes bombed Košice (Kassa). Although Hungarian authorities assumed Soviet responsibility, some speculation exists that this was a false-flag attack instigated by Germany (possibly in cooperation with Romania) to give Hungary a casus belli for joining Operation Barbarossa and the war,[19][20] although it is plausible that Soviet bombers mistook Kassa for nearby Prešov in Slovakia. Hungary declared war against the Soviets on 27 June 1941, less than 24 hours after the Košice bombing raid.

On 1 July 1941, under German instruction, the Hungarian Carpathian Group (Karpat Group) attacked the 12th Soviet Army. Attached to the German 17th Army, the Karpat Group advanced far into Soviet Ukraine, and later into southern Russia. At the Battle of Uman, fought between 3 and 8 August, the Karpat Group's mechanized corps acted as one half of a pincer that encircled the 6th Soviet Army and the 12th Soviet Army. This action resulted in the capture or destruction of twenty Soviet divisions.

In July 1941 the Hungarian government transferred responsibility for 18,000 Jews from Carpato-Ruthenian Hungary to the German armed forces. These Jews, without Hungarian citizenship, were sent to a location near Kamenets-Podolski, where in one of the first acts of mass-killing of Jews during World War II, Nazi mobile killing units shot all but two thousand of these individuals.[21][22] Bárdossy then passed the Third Jewish Law in August 1941, prohibiting marriage and sexual intercourse between Jews and non-Jews.

Six months after the mass murder at Kamianets-Podilskyi in January 1942, Hungarian troops massacred 3,000 Serbian and Jewish hostages near Novi Sad, Yugoslavia.

Worried about Hungary's increasing reliance on Germany, Admiral Horthy forced Bárdossy to resign and replaced him with Miklós Kállay, a veteran conservative of Bethlen's government. Kállay continued Bárdossy's policy of supporting Germany against the Red Army while also initiating negotiations with the Allies. Hungarian participation in Operation Barbarossa during 1941 was limited in part because the country had no real large army before 1939, and time to train and equip troops had been short. But by 1942, tens of thousands of Hungarians were fighting on the eastern front in the Royal Hungarian Army.

During the Battle of Stalingrad, the Hungarian Second Army suffered terrible losses. The Soviet breakthrough at the Don River sliced directly through the Hungarian units. Shortly after the fall of Stalingrad in January 1943, the Soviets crushed the Hungarian Second Army at the Battle of Voronezh. Ignoring German orders to stand and fight to the death, the bewildered Hungarian troops, fighting without antitank weaponry or armored support, harassed by partisan groups and Soviet air attacks, and having to endure the Russian winter weather, tried in vain to retreat. Most of the survivors were taken prisoner by the Soviet army, and total casualties numbered more than 100,000 men. The Hungarian army ceased to exist as an effective fighting force, and the Germans pulled them from the front.

While Kállay was prime minister, the Jews endured increased economic and political repression, although many, particularly those in Budapest, were temporarily protected from the final solution. For most of the war, the Hungarian Jews lived an uneasy existence. They were deprived of most freedoms, but were not subjected to physical harm, and Horthy tried to contain anti-Semitic groups such as the Arrow Cross. After two years of war against the Soviet Union, Prime Minister Miklós Kállay began peace negotiations with the United States and the United Kingdom in autumn of 1943,[4] and 1944 Horthy secretly started peace talks with the Soviet Union and attempted to create the National Centrist-Governance (Nemzeti Középkormány) through the series of secret negotiations with the Hungarian Front (an anti-German rebel group) to push back the management's pro-German far-right endeavors. Berlin was already suspicious of the Kállay's government, and in September 1943, the German General Staff prepared a project to invade and occupy Hungary. At the request of the Allies, there were no connections made with the Soviets.

German occupation of Hungary

Aware of Kállay's deceit and fearing that Hungary might conclude a separate peace, in March 1944 Hitler launched Operation Margarethe and ordered German troops to occupy Hungary. Horthy was confined to a castle, in essence, placed under house arrest. Döme Sztójay, an avid supporter of the Nazis, became the new prime minister. Sztójay governed with the aid of a German military governor, Edmund Veesenmayer. The Hungarian populace was not happy with their nation effectively reduced to a German protectorate, but Berlin threatened to occupy Hungary with Slovak, Croat, and Romanian troops if they did not comply. The threat of these ancestral enemies on Hungarian soil was seen as far worse than German control. Hungary kept entire divisions on the Romanian border while the troops of both nations were fighting and dying together in the Russian winter.

As the Soviets pushed westward, Sztojay's government mustered new armies. The Hungarian troops again suffered terrible losses, but now had a motive to protect their homeland from Soviet occupation.

In August 1944, Horthy replaced Sztójay with the anti-fascist general Géza Lakatos. Under the Lakatos regime, acting interior minister Béla Horváth ordered gendarmes to prevent the deportation of Hungarian citizens. The Germans were unhappy with the situation but could not do a great deal about it. Horthy's actions thus bought the Jews of Budapest a few months of time.

Soviet occupation of Hungary

In September 1944, Soviet forces crossed the Hungarian border. On 15 October, Horthy announced that Hungary had asked for an armistice with the Soviet Union. The Hungarian army ignored Horthy's orders, fighting desperately to keep the Soviets out. The Germans launched Operation Panzerfaust and, by kidnapping his son Miklós Horthy Jr., forced Horthy to abrogate the armistice, depose the Lakatos government, and name the leader of the Arrow Cross Party, Ferenc Szálasi, as prime minister. Horthy resigned and Szálasi became prime minister of a new Government of National Unity (Nemzeti Összefogás Kormánya) controlled by the Germans. Horthy was taken to Germany as a prisoner but survived the war and spent his last years exiled in Portugal, dying in 1957.

In cooperation with the Nazis, Szálasi attempted to resume deportations of Jews, but Germany's rapidly disintegrating communications largely prevented this from happening. Nonetheless, the Arrow Cross launched a reign of terror against the Jews of Budapest. Thousands were tortured, raped and murdered in the last months of the war, their property looted or destroyed. Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg saved thousands of Budapest's Jews using Swedish protective passports. He was ultimately taken prisoner by the Soviets and died some years later in a labor camp. Other foreign diplomats such as Nuncio Angelo Rotta, Giorgio Perlasca, Carl Lutz, Friedrich Born, Harald Feller, Angel Sanz Briz and George Mandel-Mantello also organized false papers and safehouses for Jews in Budapest. Of the approximately 800,000 Jews residing within Hungary's expanded borders of 1941, only 200,000 (about 25%) survived the Holocaust.[23] An estimated 28,000 Hungarian Roma were also killed as part of the Porajmos.

Soon Hungary itself became a battlefield. Szálasi promised a Greater Hungary and prosperity for the peasants, but in reality Hungary was crumbling and its armies were slowly being destroyed. As an integral part of German general Maximilian Fretter-Pico's Armeegruppe Fretter-Pico, the reformed Hungarian Second Army enjoyed a modest level of combat success. From 6 to 29 October 1944 during the Battle of Debrecen, Armeegruppe Fretter-Pico managed to achieve a major win on the battlefield. Avoiding encirclement itself, it encircled and severely mauled three Soviet tank corps serving under the Mobile Group of Issa Pliyev. Earlier in the same battle, Mobile Group Pliyev had sliced through the Hungarian Third Army. But success was costly and, unable to replace lost armor and heavy artillery munitions, the Hungarian Second Army was defeated on 1 December 1944. The remnants of the Second Army were incorporated into the Third Army.

In October 1944, the Hungarian First Army was attached to the German 1st Panzer Army, participating defensively against the Red Army's advance toward Budapest. On 28 December 1944, a provisional government was formed in Hungary under acting prime minister Béla Miklós. Szálasi and Miklós each claimed to be the legitimate head of government. The Germans and pro-German Hungarians loyal to Szálasi fought on.

The Soviets and Romanians completed the encirclement of Budapest on 29 December 1944. The battle for the city turned into the Siege of Budapest. While Kállay himself was in the Dachau Concentration Camp at the time, the Sovereignty Movement (Függetlenségi Mozgalom) he supported, fought alongside the Soviets. Famous people from the group were Szent-Györgyi Albert biochemist (who was proposed to be the prime minister) and Várnai Zseni revolutionary writer.[24] During the fight, most of what remained of the Hungarian First Army was destroyed about 200 kilometres (120 mi) north of Budapest in a running battle from 1 January to 16 February 1945. On 20 January 1945, representatives of the Miklós provisional government signed an armistice in Moscow. In January 1945, 32,000 ethnic Germans from within Hungary were arrested and transported to the Soviet Union as forced laborers. In some villages, the entire adult population were taken to labor camps in the Donets Basin.[25][26]: 21 Many died there as a result of hardships and poor treatment. Overall, between 100,000 and 170,000 Hungarian ethnic Germans were transported to the Soviet Union.[27]: 38

The remaining German and Hungarian units within Budapest surrendered on 13 February 1945. Although the German forces in Hungary were generally defeated, the Germans had one more surprise for the Soviets. On 6 March 1945, the Germans launched the Lake Balaton Offensive, attempting to hold on to the Axis' last source of oil. It was their final operation of the war and it quickly failed. By 19 March 1945, Soviet troops had recaptured all the territory lost during the 13-day German offensive.[28]: 182

After the failed offensive, the Germans in Hungary were eliminated. Most of what remained of the Hungarian Third Army was destroyed about 50 kilometres (31 mi) west of Budapest between 16 and 25 March 1945. From 26 March and 15 April, the Soviets and Bulgarians launched the Nagykanizsa–Körmend Offensive and more Hungarian remnants were destroyed as part of Army Group South fighting alongside the 2nd Panzer Army. By the start of April, the Germans, with the Arrow Cross in tow, had completely vacated Hungarian soil.

Retreat into Germany

Officially, Soviet operations in Hungary ended on 4 April 1945, when the last German troops were expelled. Some pro-fascist Hungarians such as Szálasi escaped—for a time—with the Germans. A few pro-German Hungarian units fought on until the end of the war. Units such as the Szent László Infantry Division ended the war in southern Austria.

On 8 May 1945 at 4:10 p.m., the 259th Infantry Regiment of the 65th Infantry Division (commanded by Major General Stanley Eric Reinhart) of the United States Army was authorized[citation needed] to accept the surrender of the 1st Hungarian Cavalry Division (1st Huszár Division,[29] Hungarian: Huszár Hadosztály) and of the 1st Hungarian Armoured Division,[30] then in the area of present-day Austria. Surrender and movement across the Enns River had to be completed prior to midnight.

In the town of Landsberg in Bavaria, a Hungarian garrison stood in parade formation to surrender as Americans forces advanced through the area very late in the war.[31] A few Hungarian soldiers ended the war in Denmark in some of the last territory not yet occupied by the Allies.

List of major engagements

This is a list of battles and other combat operations in World War II in which Hungarian forces took part.

Oppression at home

The Holocaust

On 19 March 1944 German troops occupied Hungary, prime minister Miklós Kállay was deposed and soon mass deportations of Jews to German death camps in occupied Poland began. SS-Obersturmbannführer Adolf Eichmann went to Hungary to oversee the large-scale deportations. Between 15 May and 9 July, Hungarian authorities deported 437,402 Jews. All but 15,000 of these Jews were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau,[21] and 90% of those were immediately killed. It has been estimated that one-third of the murdered victims at Auschwitz were Hungarian.[32] Sztojay, unlike previous prime ministers, answered mostly to Berlin and was thus able to act independently of Horthy. However, reports of the conditions in the concentration camps led the admiral to resist his policies.

In early July 1944, Horthy stopped the deportations, and after the failed attempt on Hitler's life, the Germans backed off from pressing Horthy's regime to continue further, large-scale deportations, although some smaller groups continued to be deported by train. In late August, Horthy refused Eichmann's request to restart the deportations. Himmler ordered Eichmann to leave Budapest.[33]

Forced labor

The forced labor service system was introduced in Hungary in 1939. The system affected primarily the Jewish population, but many people belonging to minorities, sectarians, leftists and Roma were also inducted.

Thirty-five thousand to 40,000 forced laborers, mostly Jews or of Jewish origin, served in the Hungarian Second Army, which fought in the USSR (see below). Eighty percent of them—28,000 to 32,000 people—never returned; they died either on the battlefield or in captivity.

Approximately half of the 6,000 Jewish forced laborers working in the copper mines in Bor, Yugoslavia (now Serbia) were executed by the Germans during the death march from Bor to Győr in August–October 1944, including the 35-year-old poet Miklós Radnóti, shot at the Hungarian village of Abda for being too weak to continue after a savage beating.[34][35]

Resistance movement

In autumn of 1941 anti-German demonstrations took place in Hungary. On 15 March 1942, the anniversary of the outbreak of the 1848–49 War of Independence, a crowd of 8,000 people gathered at the Sándor Petőfi monument in Budapest to demand an "independent democratic Hungary". The underground Hungarian Communist Party published a newspaper and leaflets, 500 communist activists were arrested and the party's leaders Ferenc Rózsa and Zoltán Schönherz were executed.[citation needed]

The Hungarian underground opposition contributed little to the military defeat of Nazism. In July 1943 the Smallholders Party adopted Endre Bajcsy-Zsilinszky's policy of working more closely with the Hungarian Social Democratic Party and the Communists and on 31 July demanded from the government an end to hostilities and joining the Allies even at the price of armed conflict with Germany. At the beginning of August 1943 a programme of action was formally concluded with the Social Democrats and on 11 September they issued a joint declaration against the war on the side of Germany.[citation needed]

Various opposition groups deprived of their leaders most of whom had been arrested by the Gestapo after the German occupation in March 1944 joined forces in May 1944 in the Communist-inspired Hungarian Front (Magyar Front). They demanded a "new struggle of liberation" against the German occupation forces and their collaborators and called for the creation of a new democratic Hungary after the war. The representatives of the Hungarian Front, being informed by Horthy of plans for an armistice on 11 October, founded the Committee of Liberation of the Hungarian National Uprising on 11 November 1944. Although immediately weakened by the arrest and execution of its leaders, with General János Kiss among them, it called for an armed uprising against the German forces which took the form of limited isolated partisan actions and attacks on German military installations.[36]

During the first months of Arrow Cross rule, resistors infiltrated the newly formed KISKA security division and used it as legal cover.[37]

Armed and violent resistance began shortly after the Third Reich occupied Hungary; most of the resistance groups held to left-wing views or consisted of fighters from neighbouring countries. There were Communist partisan detachments which were sent to Hungary from the Soviet Union, but these failed to turn their activities into a popular movement. Sándor Nógrádi who was parachuted from the USSR in 1944[38] became the commander of such guerilla unit. In the Hungarian People's Republic, the Communist guerillas sent from the USSR and their activities were magnified and exaggerated, while the other partisan groups and non-violent activists, including some far-right intellectuals, were silenced, and today organized Communist partisan activity in Hungary is largely considered a myth, possibly because of the treatment of the subject by the Marxist-Leninist historiography. Hungarian historian Ákos Bartha noted that the "non-Communist" resistance in Hungary "have been relegated to the no-man's land in terms of memory politics in the 21st century", while László Bernát Veszprémy writes that "the current consensus of mainstream historiography is that there was no such thing as armed resistance in Hungary during the German occupation." However, he cites cases of armed struggle described by Hungarian and German authorirties and argues that the materials of "the national committees after the Soviet occupation" and "people’s prosecutors cases and the people's tribunal cases" "still need to be explored by Hungarian historians."[39][40]

In December 1944, the USSR supported the formation of a Hungarian government alternate to Arrow Cross regime which was headed by Béla Miklós. During the Battle of Budapest, the USSR used the Volunteer Regiment of Buda composed of the Hungarian POWs; it was to become a Hungarian division of the Red Army, but the battle had finished by the time the division was formed.

Peace treaty

By 2 May 1945, Hitler was dead and Berlin surrendered. On 7 May, General Alfred Jodl, the German Chief of Staff, signed the surrender of Germany. On 23 May, the "Flensburg Government" was dissolved. On 11 June, the Allies agreed to make 8 May 1945 the official "Victory in Europe" day.[28]: 298

The Treaty of Peace with Hungary[41] signed on 10 February 1947 declared that "The decisions of the Vienna Award of 2 November 1938 are declared null and void" and Hungarian boundaries were fixed along the former frontiers as they existed on 1 January 1938, except a minor loss of territory on the Czechoslovakian border. Two-thirds of the ethnic German minority (202,000 people) was deported to Germany in 1946–48, and there was a forced "population exchange" between Hungary and Czechoslovakia.

On 1 February 1946, the Kingdom of Hungary was formally abolished and replaced by the Second Republic of Hungary. Post-war Hungary was eventually taken over by a Soviet-allied government and became part of the Eastern Bloc. The People's Republic of Hungary was declared in 1949 and lasted until the Revolutions of 1989 and the End of Communism in Hungary.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Hungary: The Unwilling Satellite Archived 16 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine John F. Montgomery, Hungary: The Unwilling Satellite. Devin-Adair Company, New York, 1947. Reprint: Simon Publications, 2002.

- ^ "On this Day, in 1940: Hungary signed the Tripartite Pact and joined the Axis". 20 November 2020.

- ^ Ungváry, Krisztián (23 March 2007). "Hungarian Occupation Forces in the Ukraine 1941–1942: The Historiographical Context". The Journal of Slavic Military Studies. 20 (1): 81–120. doi:10.1080/13518040701205480. ISSN 1351-8046. S2CID 143248398.

- ^ a b Gy Juhász, "The Hungarian Peace-feelers and the Allies in 1943." Acta Historica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 26.3/4 (1980): 345-377 online

- ^ Gy Ránki, "The German Occupation of Hungary." Acta Historica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 11.1/4 (1965): 261-283 online.

- ^ Dawidowicz, Lucy. The War Against the Jews, Bantam, 1986, p. 403; Randolph Braham, A Magyarországi Holokauszt Földrajzi Enciklopediája (The Geographic Encyclopedia of the Holocaust in Hungary), Park Publishing, 2006, Vol 1, p. 91.

- ^ Crowe, David. "The Roma Holocaust," in Barnard Schwartz and Frederick DeCoste, eds., The Holocaust's Ghost: Writings on Art, Politics, Law and Education, University of Alberta Press, 2000, pp. 178–210.

- ^ Pogany, Istvan, Righting Wrongs in Eastern Europe, Manchester University Press, 1997, pp.26–39, 80–94.

- ^ '2. Zusatzvertrag zum deutsch-ungarischen Wirtschaftsabkommen von 1931 (Details Archived 4 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ a b Thomas, The Royal Hungarian Army in World War II, pg. 11

- ^ "AZ ELSŐ BÉCSI DÖNTÉS SZÖVEGE". www.arcanum.hu (in Hungarian). Arcanum Adatbázis Kft.

- ^ "Slovakia". U.S. Department of State.

- ^ Károly Kocsis, Eszter Kocsisné Hodosi, Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minorities in the Carpathian Basin, Simon Publications LLC, 1998, p. 116-153 [1][permanent dead link]

- ^ Hitchins, Keith (1994), Romania: 1866–1947, Oxford History of Modern Europe, Oxford: Clarendon Press, ISBN 978-0-19-158615-6, OCLC 44961723

- ^ Hungary Archived 3 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine – Shoah Foundation Institute Visual History Archive

- ^ "Délvidék visszacsatolása". www.arcanum.hu (in Hungarian). Arcanum Adatbázis Kft.

- ^ Slobodan Ćurčić, Broj stanovnika Vojvodine, Novi Sad, 1996.

- ^ Géza Vasas – A ruszin autonómia válaszútjain (1939. március-szeptember) – On the crossroads of Ruthenian autonomy (March–September 1939), [2]

- ^ Dreisziger, N.F. (1972). "New Twist to an Old Riddle: The Bombing of Kassa (Košice), June 26, 1941". The Journal of Modern History. 44 (2). The University of Chicago Press: 232–242. doi:10.1086/240751. S2CID 143124708.

- ^ "Бомбежка Кошице" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 15 October 2011.

- ^ a b Holocaust in Hungary Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Holocaust Memorial Centre.

- ^ "Hungary Before the German Occupation". Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- ^ Victims of Holocaust Archived 11 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine – Holocaust Memorial Centre.

- ^ "Ellenállás Magyarországon | Magyarok a II. világháborúban | Kézikönyvtár". www.arcanum.com (in Hungarian). Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ Wasserstein, Bernard (17 February 2011). "European Refugee Movements After World War Two". BBChistory. Archived from the original on 19 July 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ Ther, Philipp (1998). Deutsche Und Polnische Vertriebene: Gesellschaft und Vertriebenenpolitik in SBZ/ddr und in Polen 1945–1956. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-35790-3.

- ^ Prauser, Steffen; Rees, Arfon (December 2004). "The Expulsion of 'German' Communities from Eastern Europe at the end of the Second World War" (PDF). EUI Working Paper HEC No. 2004/1. San Domenico, Florence: European University Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ a b The Decline and Fall of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan, Hans Dollinger, Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 67-27047

- ^

Campaign: Fortress Budapest. Bolt Action, volume 27. Oxford: Bloomsbury Publishing. 21 March 2019. pp. 146–147. ISBN 9781472835710. Retrieved 28 November 2024.

The 1st Cavalry Division was mobilised in April 1944 under pressure from the Germans [...]. [...] On 23 September the now renamed 1st Huszár Division returned to Budapest [...].

- ^ Eduardo Manuel Gil Martínez (24 October 2023). Hungarian armoured units during the Second World War. Witness to War. Soldiershop Publishing. ISBN 9791255890379. Retrieved 28 November 2024.

- ^ Stafford, Endgame, 1945, p. 242.

- ^ Gábor Kádár – Zoltán Vági: Magyarok Auschwitzban. (Hungarians in Auschwitz) In Holocaust Füzetek 12. Budapest, 1999, Magyar Auschwitz Alapítvány-Holocaust Dokumentációs Központ, pp. 92–123.

- ^ Robert J. Hanyok (2004). "Eavesdropping on Hell: Historical Guide to Western Communications Intelligence and the Holocaust, 1939–1945" (PDF). NATIONAL SECURITY AGENCY, UNITED STATES CRYPTOLOGIC HISTORY. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016.

In late July there was a lull in the deportations. After the failed attempt on Hitler's life, the Germans backed off from pressing Horthy's regime to continue further, large-scale deportations. Smaller groups continued to be deported by train. At least one German police message decoded by GC&CS revealed that one trainload of 1,296 Jews from the town of Sarvar in western Hungary Hungarian Jews being rounded up in Budapest (Courtesy: USHMM) had departed for Auschwitz on August 4.112 In late August Horthy refused Eichmann's request to restart the deportations. Himmler ordered Eichmann to leave Budapest

- ^ Gilbert, Martin (1988). Atlas of the Holocaust. Toronto: Lester Publishing Limited. pp. 10, 206. ISBN 978-1-895555-37-0.

- ^ Perez, Hugo (2008). "Neither Memory Nor Magic: The Life and Times of Miklos Radnoti". M30A Films. Archived from the original on 9 October 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ "THE HISTORY OF HUNGARY". Archived from the original on 6 May 2016.

- ^ Juhász, Gyula (1988). "Problems of the Hungarian Resistance after the German Occupation, 1944". In William Deakin; Elisabeth Barker; Jonathan Chadwick (eds.). British Political and Military Strategy in Central, Eastern and Southern Europe in 1944. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 180–189.

- ^ Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern. Hoover Press. 1973. ISBN 978-0-8179-8403-8.

- ^ "The Forgotten Hungarian Resistance in the Second World War — A Review of Ákos Bartha's New Book | Hungarian Conservative". 23 May 2023.

- ^ "Without a Single Gunshot? — Examples of Armed Resistance during the German Occupation | Hungarian Conservative". 19 March 2024.

- ^ Treaty of Peace with Hungary Archived 4 December 2004 at the Wayback Machine

References and further reading

- Armour, Ian. "Hungary" in The Oxford Companion to World War II edited by I. C. B. Dear and M. R. D. Foot (2001) pp 548–553.

- Borhi, László. "Secret Peace Overtures, the Holocaust, and Allied Strategy vis-à-vis Germany: Hungary in the Vortex of World War II." Journal of Cold War Studies 14.2 (2012): 29-67.

- Braham, Randolph (1981). The Politics of Genocide: The Holocaust in Hungary. Columbia University Press.

- Case, Holly. Between states: the Transylvanian question and the European idea during World War II (Stanford UP, 2009).

- Cesarani, D. ed. Genocide and Rescue: The Holocaust in Hungary (Oxford Up, 1997).

- Cornelius, Deborah S. Hungary in World War II: Caught in the Cauldron (Fordham UP, 2011).

- Czettler, Antal. "Miklos Kallay's attempts to preserve Hungary's independence." Hungarian Quarterly 41.159 (2000): 88-103.

- Dollinger, Hans. The Decline and Fall of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan: A Pictorial History of the Final Days of World War II (1967)

- Eby, Cecil D. Hungary at war: civilians and soldiers in World War II (Penn State Press, 1998).

- Don, Yehuda. "The Economic Effect of Antisemitic Discrimination: Hungarian Anti-Jewish Legislation, 1938-1944." Jewish Social Studies 48.1 (1986): 63-82 online.

- Dreisziger, N. F. "Bridges to the West: The Horthy Regime's ‘Reinsurance Policies’ in 1941." War & Society 7.1 (1989): 1-23.

- Fenyo, D. Hitler, Horthy, and Hungary: German-Hungarian Relations, 1941–1944 (Yale UP, 1972).

- Fenyö, Mario D. (1969). "Some Aspects of Hungary's Participation in World War II". East European Quarterly. 3 (2): 219–29.

- Herczl, Moshe Y. Christianity and the Holocaust of Hungarian Jewry (1993)online

- Jeszenszky, Géza. "The Controversy About 1944 in Hungary and the Escape of Budapest’s Jews from Deportation. A Response." Hungarian Cultural Studies 13 (2020): 67-74 online.

- Juhász, Gyula. "The Hungarian Peace-feelers and the Allies in 1943." Acta Historica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 26.3/4 (1980): 345-377 online

- Juhász, Gyula. "The German Occupation of Hungary." Acta Historica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 11.1/4 (1965): 261-283 online

- Juhász, G. Hungarian Foreign Policy 1919–1945 (Budapest, 1979).

- Kenez, Peter. Hungary from the Nazis to the Soviets: the Establishment of the Communist Regime in Hungary, 1944-1948 (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

- Kertesz, Stephen D. "The Methods of Communist Conquest: Hungary 1944-1947." World Politics (1950): 20-54 online.

- Kertesz, Stephen D. Diplomacy in a Whirlpool: Hungary Between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia (U of Notre Dame Press, 1953). online

- Macartney, C. A. October Fifteenth: A History of Modern Hungary 1929–1945 2 vols. (Edinburgh UP, 1956–7).

- Montgomery, John Flournoy. Hungary: The Unwilling Satellite (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2018).

- Pelényi, John. "The Secret Plan for a Hungarian Government in the West at the Outbreak of World War II." Journal of Modern History 36.2 (1964): 170-177. online

- Sakmyster, Thomas L. Hungary's Admiral on Horseback: Milós Horthy, 1918-1944 (Eastern European Monographs, 1994).

- Sakmyster, Thomas. "Miklos Horthy aud the Allies, 1945-1946: Two Documents." Hungarian Studies Review 23.1 (1996) online.

- Sipos, Péter et al. "The Policy of the United States towards Hungary during the Second World War" Acta Historica Academiae Scientiarum (1983) 29#1 pp 79–110 online.

- Stafford, David. Endgame, 1945: The Missing Final Chapter of World War II. Little, Brown and Company, New York, 2007. ISBN 978-0-31610-980-2

- Szabo, Laszlo Pal; Thomas, Nigel (2008). The Royal Hungarian Army in World War II. New York: Osprey. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-84603-324-7.

- Trigg, Jonathan (2017) [2013]. Death on the Don: The destruction of Germany's Allies on the Eastern Front, 1941-44 (2 ed.). Stroud, Gloucestershire,UK: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-7946-7.

- Ungváry, Krisztián. The Siege of Budapest: One Hundred Days in World War II (Yale UP, 2005).

- Ungváry, K. Battle for Budapest: 100 Days in World War II (2003).

- Vági, Zoltán, László Csősz, and Gábor Kádár. The Holocaust in Hungary: Evolution of a genocide. (AltaMira Press, 2013).