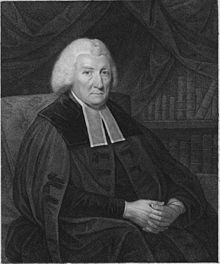

Hugh Blair

Hugh Blair | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 7 April 1718 |

| Died | 27 December 1800 (aged 82) |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Occupation(s) | theologian, author, rhetorician |

| Notable work | Sermons (1777–1801) |

Hugh Blair FRSE (7 April 1718 – 27 December 1800) was a Scottish minister of religion, author and rhetorician, considered one of the first great theorists of written discourse.

As a minister of the Church of Scotland, and occupant of the Chair of Rhetoric and Belles Lettres at the University of Edinburgh, Blair's teachings had a great impact in both the spiritual and the secular realms. Best known for Sermons, a five volume endorsement of practical Christian morality, and Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres, a prescriptive guide on composition, Blair was a valuable part of the Scottish Enlightenment.

Life

Blair was born in Edinburgh into an educated Presbyterian family. His father was John Blair, an Edinburgh merchant.[1] He was great-great-grandson of Rev. Robert Blair of St. Andrews and great nephew of Very Rev. David Blair the Moderator of the General Assembly in 1700.[2]

From an early age it was clear that Blair, a weakly child, should be educated for a life in the church. Schooled at the High School, Blair studied moral philosophy and literature at the University of Edinburgh, where he graduated M.A. at the age of twenty-one. His thesis, "Dissertatio Philosophica Inauguralis de fundamentis et obligatione legis naturae",[3] serves as a precursor to the later published Sermons in its discussion of the principles of morality and virtue.[4]

In 1741, two years after the publication of his thesis, Blair received his license as a Presbyterian preacher. Shortly thereafter, the Earl of Leven heard of Blair's popularity and presented him to the Parish Church of Collessie in Fife, as their minister.

By 1743 Blair was elected as the second charge of the Canongate Kirk, under Rev James Walker in first charge. Although some records say he reached "first charge" this is not the case.[5] Blair was appointed to the sole charge of Lady Yester's Kirk in 1754, and four years later in 1758 was translated to the second charge of the High Kirk of St Giles under Rev Robert Walker as "first charge". They became very close friends.[6] Despite being "second charge" this was nevertheless one of the highest positions that a clergyman could achieve in Scotland. Blair maintained this position for many years, during which time he published a five-volume series of his addresses entitled Sermons.

Having attained ultimate success in the church, Blair turned to matters of education. In 1757 he was presented with an honorary degree of Doctor of Divinity by the University of St Andrews[5] and began to lecture in Rhetoric and Belles Lettres for the University of Edinburgh in 1759. At first Blair taught without remuneration from the university and was paid direct by his students, but the popularity of his course led to the institution of a permanent class and Blair was made Professor Rhetoric and Belles Lettres at the university in 1762, a position ratified by King George III. He retained this position until his retirement in 1783. After retirement, Blair published several of his lectures in Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres.

In 1773 Blair was living at Argyle Square on the south side of Edinburgh's Old Town. The property was demolished in the mid-19th century to create Chambers Street.[7]

In 1777, at the point of its creation, he was appointed Chaplain to the 71st Regiment of Foot, initially based at Edinburgh Castle.[5]

In 1783 Blair was one of the founder members of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. He served as its Literary President from 1789 to 1796.

Blair's life was very full in both the public and the private spheres. As a central figure in the Scottish Enlightenment, he surrounded himself with other scholars in the movement. Hume, Carlyle, Adam Smith, Ferguson, and Lord Kames were among those Blair considered friends.

He had a summer residence in the small village of Restalrig north-east of Edinburgh.[8]

He died at home in Argyle Square on 27 December 1800.[9]

Blair is buried near his home, in Greyfriars Churchyard in Edinburgh.[1] The grave was originally unmarked, but a memorial was erected on the south-west section of Greyfriars Kirk to commemorate him, lying between tablets to Allan Ramsay and Colin MacLaurin. It is inscribed in Latin therefore gives his name as Hugo Blair.

He was succeeded in his chair at Edinburgh University by Andrew Brown (1763-1834).[10] His position as second charge of St Giles was filled by Rev George Husband Baird.[5]

Family

Blair had a very loving marriage to his cousin, Katherine Bannatine, whom he married in April 1748.[1] Katherine was the daughter of Very Rev James Bannatine minister of Trinity College Church in north-east Edinburgh. He had been Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1739.[5]

Together they had two children: a son who died at birth and a daughter Katherine (1749-1769) who died at the age of 20 i.e. both children predeceased them. Blair also outlived his wife, who died in February 1795 five years before his own death in December 1800.[4] He was described as "amiable, kind to young authors, and remarkable for a harmless, but rather ridiculous vanity and simplicity".[11]

Chronology of works

- 1739: Defundamentis et Obligatione Legis Naturæ

- 1753: The Works of Shakespeare (ed. Hugh Blair [Anon.])

- 1755: Review of Francis Hutcheson's A System of Moral Philosophy [Anon.]

- 1755: Observations on a Pamphlet (by John Bonar), entitled An Analysis of the Moral and Religious Sentiments contained in the Writings of Sopho and David Hume Esq [Anon.]

- 1760: 'Preface' [Anon.] to James Macpherson, Fragments of Ancient Poetry collected in the Highlands of Scotland and translated from the Galic or Erse Language

- 1763: A Critical Dissertation on the Poems of Ossian, the Son of Fingal

- 1777–1801: Sermons (5 vols) Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Vol. 3, Vol. 4, Vol. 5

- 1783: Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Vol. 3

Major works

Blair is best known for the publication of three major works: A Critical Dissertation on the Poems of Ossian, Son of Fingal; Sermons; and Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres.[4] While little attention is given to his other works, Blair published several other works anonymously, the most important of which is an eight-volume edition of Shakespeare's works edited by Blair.

A Critical Dissertation on the Poems of Ossian, the Son of Fingal

In 1763 Blair published A Critical Dissertation on the Poems of Ossian, his first well known openly authored publication. Blair, having long taken interest in the Celtic poetry of the Scottish Highlands, wrote a laudatory account of the poems of Ossian, the authenticity of which he maintained.[4] Blair serves as the voice of authority on the legitimacy of the poems that he himself had urged friend James Macpherson to publish in Fragments of Ancient Poetry.

The dissertation directly opposes assertions that the poems Macpherson claimed to be ancient and sublime were in fact written by several modern poets, or possibly even by Macpherson himself. After 1765 Dissertation appeared in every publication of the Ossian to give the work credibility. Blair's praise ultimately proved futile as the poems were deemed false and Macpherson was convicted of literary forgery. While this work does not speak highly of Blair's skills as a literary critic, it does provide insight into Blair's own taste, a subject that is important to his later writing.

Sermons

Blair published the first of his five volume series Sermons in 1777. It is a compilation of the sermons promoting practical Christian morality he delivered as a Presbyterian preacher. Despite the declining popularity of published religious teachings at the time, the success of Sermons paralleled Blair's success as a preacher. Though Blair's oral delivery was poor, often described as a 'burr,' he was considered the most popular preacher in Scotland. His success is credited to the ease with which the audience could follow his polite, organised style; a style that was translated easily into print.

Sermons reflects Blair's position as a member of the moderate or latitudinarian party. In many respects, Blair was socially conservative. He did not believe in radical change, as his teachings were safe and ultimately prepared for the upper classes. Blair also had liberal tendencies demonstrated in his rejection of Calvinistic doctrines such as original sin, total corruption, and damnation.

Sermons focuses on questions of morality, rather than theology, and it emphasises patriotism, action in the public sphere, and moral virtue promoted by polite secular culture. Blair encourages people to improve their natural talents through hard work, but also to be content with their appointed stations in society. He urges people to play an active role in society, to enjoy the pleasures of life, to do good works, and to maintain faith in God.

Blair's appeal to both emotion and reason, combined with his non-confrontational, moderate and elegant style made each volume of Sermons increasingly popular. Four editions were published in Blair's lifetime and a fifth shortly after his death. Each volume was met with the greatest success, as they were published in many European languages and went through several printings. Though Blair's Sermons eventually fell out of favour for lacking doctrinal definiteness—"a bucket of warm water", as one opinion puts it—they were undoubtedly influential during Blair's lifetime and for several decades after his death.

In Jane Austen's Mansfield Park, Mary Crawford, a cynical critic of the church, suggests that a wise clergyman would do better to preach Blair's sermons than his own.[12][13]

Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres

| Part of a series on |

| Rhetoric |

|---|

|

After retiring from his position as Chair of Rhetoric and Belles Lettres at the University of Edinburgh in 1783, Blair published his lectures for the first time, deeming it necessary because unauthorised copies of his work threatened the legacy of his teachings. The result is arguably Blair's most important work: Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres. Lectures, a compilation of 47 of Blair's lectures given to students at the University of Edinburgh, serves as a practical guide for youth on composition and language, a guide that makes Blair the first great theorist of written discourse.

Lectures is important not because it presents radical new theories. In fact, Blair himself admits that the work is a suffusion of his understanding of classical and modern theories of language. Lectures draws on the classic works of theorists such as Quintilian and Cicero combined with the modern works of Addison, Burke, and Lord Kames to become one of the first whole language guides. As one of the first works to focus on written discourse, rather than solely on oral discourse, Blair's Lectures is a comprehensive, accessible prescriptive composition guide that combines centuries of theory in a cohesive form.

The intention of Lectures is to provide youth with a simple, organised guide on the value of rhetoric and belles lettres in the quest for upward mobility and social success. Blair believed that social cultivation, and most importantly the proper use of polite literature and effective writing, was the key to social success. For him, an education in literature was socially useful, both in its ability to elevate one's social status and its ability to promote virtue and morality. Blair also acknowledged that a person must have virtue and personal character, as well as knowledge of literature to be an effective speaker or writer. While his lectures certainly provide ideas on how to compose texts, the focus increasing becomes the proper response to written literature. He supplies sample writings from contemporary literature to illustrate the qualities of writings so that students would identify, analyze, and imbibe those qualities. The anticipated result is that students will cultivate a proper taste, and will be able to appreciate the aesthetic qualities in fine language.

Blair's concept of taste involved two distinctive aspects of the human mind- a person's senses and a person's thought processing. Through exercise of the five senses, a person can have their taste refined and perfected. Through a person's reasoning abilities, a person can determine what produces genuine pleasure and what produces something inauthentic. When combining exercise and reason, the critic develops taste-delicacy and correctness of taste. Taste delicacy ties into a critic's senses, making them stronger and more accurate when it comes to sense of sight, sound, smell, taste etc. Correctness of taste ties into a critic's logic process, giving the critic the ability to make a judgment and appraise the merit of something. This also makes it easier to recognize specifically what is good and genuine and what isn't pure or legitimate.[14]

While Blair's outline of the requirements for an excellent speaker or writer is an important aspect of Lectures, the work covers a very broad scope of issues relating to composition. Blair's primary considerations are the issues of taste, language, style, and eloquence or public speaking. As well, Blair provides a critical examination of what he calls "the most distinguished species of composition, both in prose and verse" (15).

As an adherer to Scottish common sense realism, Blair's theories are founded in the belief that the principles of rhetoric evolve from the principles of nature. Blair's definition of taste reflects this sentiment: "The power of receiving pleasure from the beauties of nature and art: (15). His analysis of the nature of taste is one of his most important contributions to compositional theories because taste, according to Blair, is foundational to rhetoric and necessary for successful written and spoken discourse.

While Blair's work is generally a safe composite of multiple theories, it contains many valuable insights, such as the aforementioned analysis of taste. Blair's discussion of the history of written discourse is another important contribution to composition theory because this history was previously neglected. As well, Blair's naming and defining of four generic categories of writing: historical writing, philosophical writing, fictitious history, and poetry, and his analysis of the different parts of discourse plays an important role in the development of later compositional theories. One of Blair's more radical ideas is the rejection of Aristotelian figures of speech such as tropes. Blair argues that invention is the result of knowledge and cannot be aided by devices of invention as outlined by classic theorists. Though Blair rejects this traditional method of discourse, his work is still prescriptive in nature.

Blair's Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres combines the fundamental principles of belletristic rhetoric and literary theory in a concise, accessible form. Drawing on classic and modern theories, Blair's work is the most comprehensive prescriptive guide on composition in the 18th century. It enjoyed tremendous success for nearly a century, as 130 editions were published in numerous European languages. This work proved a best seller in Europe, for instance in Italy went through at least a dozen different editions, but the best remains that by Giambattista Bodoni in 1801. It was known in Italy as Ugone Blair.

Influence

Blair wrote in a time when print culture was flourishing and traditional rhetoric was falling out of favour. By focusing on issues of cultivation and upward mobility, Blair overshadowed the prevailing opinions of rhetoric and capitalised on the 18th century belief in the potential to rise above one's station. At this time, new money industrialists and merchants caused the middle class to rise and the English empire to grow. Blair's optimistic view that upward mobility could be affected by an understanding of eloquence and refined literature fit perfectly with the mentality of the time. In particular, the ideas presented in Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres were adapted in many prestigious institutions of learning and served as the guide on composition for many years. The Lectures were predominantly popular in the United States, with colleges such as Yale and Harvard implementing Blair's theories.

After the authenticity of the Ossian poems was disproved, A Critical Dissertation on the Poems of Ossian caused a decline in Blair's credibility. Sermons was criticised for its sentimentality and lack of doctrinal definiteness and it failed to adapt to changing tastes. Lectures too did not maintain its popularity as theorists such as Whately and Spencer, drawing on Blair's theories, dominated the domain of composition theory.

A portrait of Blair's Spanish translator, José Luis Munárriz, painted in 1815 by Goya, hangs in the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid. Munárriz holds one of Blair's books in his hands.

References

- ^ a b c Waterston & Shearer 2006, p. 90.

- ^ "Rev. David Blair, Minister Edinburgh".

- ^ Blair, Hugh (1739). Dissertatio Philosophica Inauguralis de fundamentis et obligatione legis naturae. hdl:1842/10330.

- ^ a b c d Stephen 1886.

- ^ a b c d e Fasti Ecclesiae Scoticanae; by Hew Scott

- ^ Kay's Original Portraits vol.1: Rev Robert Walker

- ^ Williamson's Edinburgh Street Directory 1773

- ^ Grant's Old and New Edinburgh vol. 5, p. 136

- ^ Edinburgh Post Office Directory 1800

- ^ "THE ACADIAN FRENCH" Nova-Scotia Archive

- ^ Cousin 1910.

- ^ Austen, Jane Mansfield Park, ch. 9 (Kindle Locations 1256-1257).

- ^ Ross, Josephine. Jane Austen: A Companion, ch. 4 Thistle Publishing. Kindle Edition.

- ^ The Rhetoric of Western Thought: Third Edition.

Sources

- Golden, J.L., Goodwin, F.B., Coleman, W.E., Sproule, J.M. The Rhetoric of Western Thought, Chapter Six. p. 135

Cousin, John William (1910), "Blair, Hugh", A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature, London: J. M. Dent & Sons – via Wikisource

Cousin, John William (1910), "Blair, Hugh", A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature, London: J. M. Dent & Sons – via Wikisource- Stephen, Leslie (1886). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 05. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 160–161.

- Waterston, Charles D; Shearer, A Macmillan (July 2006). Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002: Biographical Index (PDF). Vol. I. Edinburgh: The Royal Society of Edinburgh. ISBN 978-0-902198-84-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2006. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

Further reading

- Schmitz, Robert M., "Hugh Blair", King's Crown Press, New York (1948), 162 pages.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Chambers, Robert; Thomson, Thomas Napier (1857). . A Biographical Dictionary of Eminent Scotsmen. Vol. 1. Glasgow: Blackie and Son. pp. 251–56 – via Wikisource.

- Corbett, Edward P. J. "Hugh Blair as an Analyzer of English Prose Style." College Composition and Communication 9(2): 93–103. 1958.

- Downey, Charlotte. "Introduction." Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres.Delmar, N.Y.: Scholars' Facsimiles & Reprints, 1993. ISBN 0-8093-1907-1

- Hill, John. An Account of the Life and Writings of Dr. Hugh Blair,

- Ulman, H. Lewis. Things, Thoughts, Words, and Actions: The Problem of Language in Late Eighteenth-Century British Rhetorical Theory. Illinois: Southern Illinois Press, 1994. ISSN 0161-7729

External links

- Hugh Blair at James Boswell – a Guide

- Hugh Blair at MSU – a Website on Hugh Blair's life and philosophy

- Hugh Blair at Thoemmes Continuum – an Encyclopedia article

- Great Scots at Electric Scotland – an Article on Hugh Blair's legacy as a Scottish theorist